Anita Charles, senior lecturer in education and director of secondary teacher education at Bates, likes to illustrate a key concept in education by holding one hand 6 inches above the other, representing the potential of teaching and learning.

Above her hands, the material is too hard: A student might feel overwhelmed. Below is too easy, leading to boredom and complacency. In between her hands is what psychologists and education professionals call the “zone of proximal development,” a complex and fluid space for growth.

As the coronavirus pandemic upends every aspect of life, and presents unique challenges to students, teachers, and parents, Charles reminds us that the zone of proximal development — the ability to learn something meaningful — exists outside the traditional classroom.

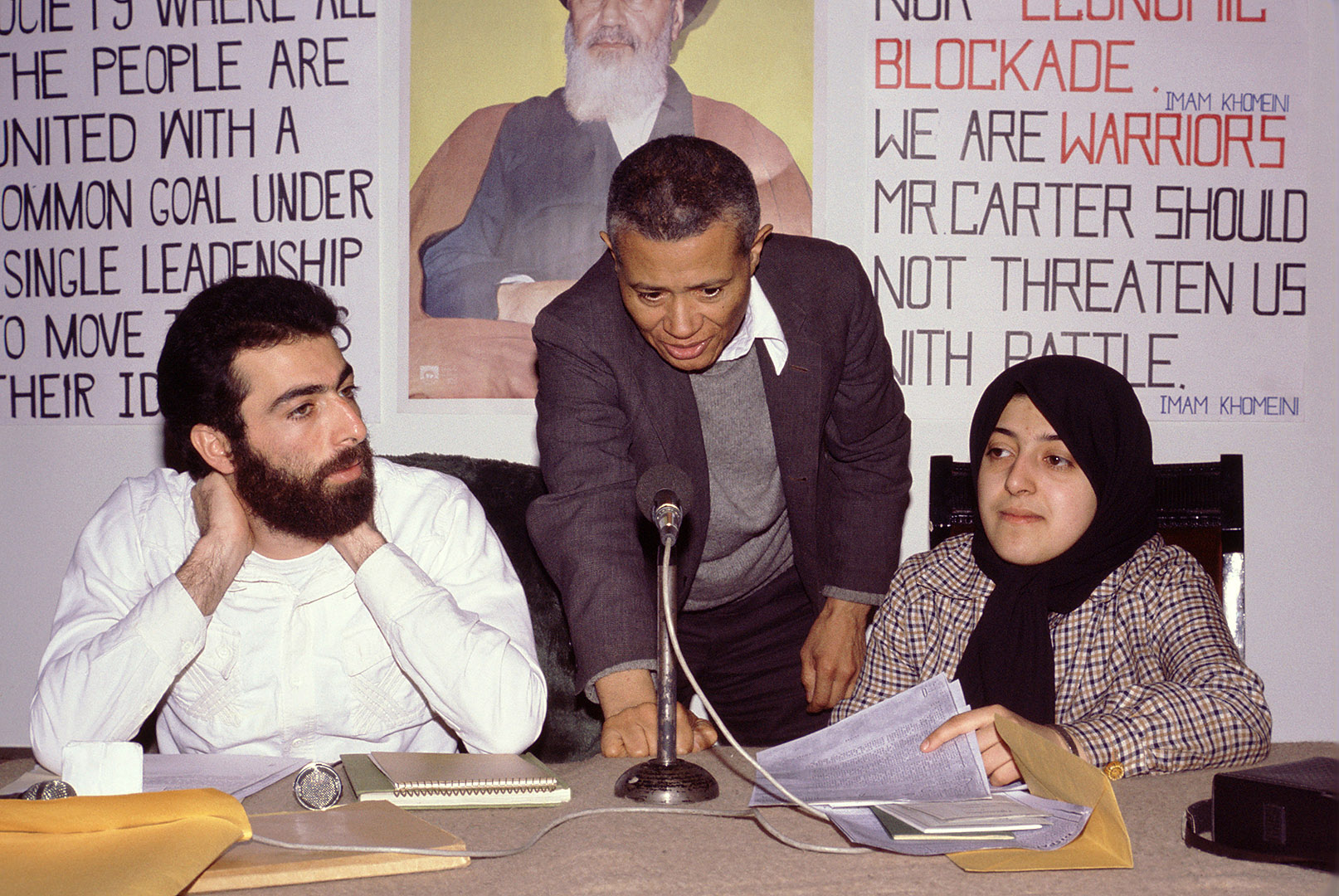

Senior Lecturer in Education Anita Charles teaches a course in 2018. Also the director of secondary teacher education at Bates, Charles has been worried about the inequalities that remote learning might produce — but she’s confident that teachers can adapt to the new normal. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“If I’m learning new technologies, then I’m stretching myself in the zone of proximal development,” Charles says. “If I’m at home, and I’m working with a child, I may be learning new skills. A child may be learning a new routine that’s unusual to them.

“Teaching and learning don’t stop. We’re redefining them, we’re recalibrating them, we’re picking up and keeping on moving within that zone.”

Charles has spent the past weeks thinking about that recalibration. Like many teachers and observers of education, she’s worried about whether and how the services that schools provide, like meals, technology, social interaction, and speech and occupational therapy, translate to a remote environment, particularly for poorer students and those with disabilities. But she’s confident that teachers and families are rising to the challenge.

For teachers and families who are now living that recalibration — making the massive adjustment to remote teaching while caring for themselves and their families — completing traditional coursework is often taking a back seat.

“We’re redefining them, we’re recalibrating them, we’re picking up and keeping on moving.”

That’s okay, Charles says. When school buildings close, teachers should be — and are — focusing more on maintaining connections with their students. “Relationships take priority over academics right now, and I would say that’s true always,” Charles says. “We build the learning on those connections.”

Kylie Martin ’19, a recent graduate of the Bates teacher education program, is an English teacher at Maine’s Poland Regional High School. The school is part of a rural Maine district and is confronting many of the challenges facing rural schools across the United States, such as accessing technology. In fact, a portion of one town in the district, Minot, which borders Lewiston-Auburn, still does not have access to high-speed internet.

“As time progresses, the emotional toll” of not going to a physical school deepens, Martin says. She video-chats with students, checking in and reminding them that they are resilient. “I want to see their faces and let them know I’m thinking of them,” she says.

It’s not a perfect way to meet with her students — many of them don’t like being on camera. Of all things, the social media app TikTok has proven quite effective.

“I post random bits of my life and self-care tactics I’m doing at home, just to help kids feel connected through social media,” she says. “I’ve gotten a lot of positive feedback.”

Andrew Jarboe ’05, a high school U.S. history teacher at Match, a pre-K–12 charter school in Boston, is also focusing on connections. Before the pandemic, he had plenty of face-to-face time with his students, including bringing some of them to a debate workshop at Bates. The challenges that some of his students have always faced are now exponentially greater.

Kylie Martin ’19, a first-year teacher at Poland (Maine) Regional High School, says that sharing “random bits of my life” — such as teaching from her home deck — with her students on social media has helped keep her connected to her students, and they with her. (Courtesy Kylie Martin).

Some have family members with COVID-19. Some are working to support the family or taking care of younger siblings.

“It must be especially challenging for the child who is trying to figure out how to learn remotely while also juggling poverty, or sickness, or hunger, or childcare,” he says.

Jarboe says that the first week after the school building closed its doors, the faculty rushed to establish contact virtually with students and families, making sure they were ready for the new learning environment and handing out Chromebooks if they needed them.

“Academics were secondary to connecting with kids, and rightly so,” he says.

Prioritizing relationships and connections doesn’t mean students can’t focus on traditional learning, Charles says. In fact, working on subjects like math and reading every day might offer students and parents a sense of structure and consistency.

“It must be especially challenging for the child who is trying to figure out how to learn remotely while also juggling poverty, or sickness, or hunger, or childcare.”

“There’s some truth to the position that we should not be putting pressure on kids to be doing academic learning,” Charles says, “but there’s a lot of value to continuing with what we perceive is classwork. It provides some routine. To sit down with a math worksheet is within kids’ control.”

Sunny Hong ’16 is a Spanish teacher at the Maine School of Science and Mathematics, a magnet residential high school in Limestone. When the students went home and remote classes began, Hong quickly realized that certain practices — like asking students to do an assignment in an hour, when they have wildly different internet connections — were not going to work anymore.

Instead, she’s been trying to get her students to learn as much Spanish as they can while enjoying themselves. She’s having them listen to music, watch movies, play games, and learn about the histories of Spanish-speaking communities in the United States. If they learn some vocabulary and grammar along the way, all the better.

“I’m not worrying a whole lot about covering everything they’re supposed to cover this year,” Hong says. “We’re all beyond that point. It’s about, how can they get the most out of this experience?”

Through trial and error, Jarboe and his colleagues at Match devised a system of remote learning using what have become ubiquitous terms in education: synchronous, or live, lessons; and asynchronous learning, using learning materials students can access anytime.

Jarboe’s students, regardless of Advanced Placement or honors level, all have the opportunity to meet with him through Zoom in the mornings; most don’t or can’t.

Otherwise, “I’ve done away with any sort of day-to-day updates or assignments,” he says. “Kids can access our Google Classroom where they will find that week’s work. They can complete the work whenever they want, and so long as it is turned in by the end of the week, I’ll be satisfied.

“The truth is, even if the work isn’t turned in on time and arrives in my inbox much later, that’s OK.”

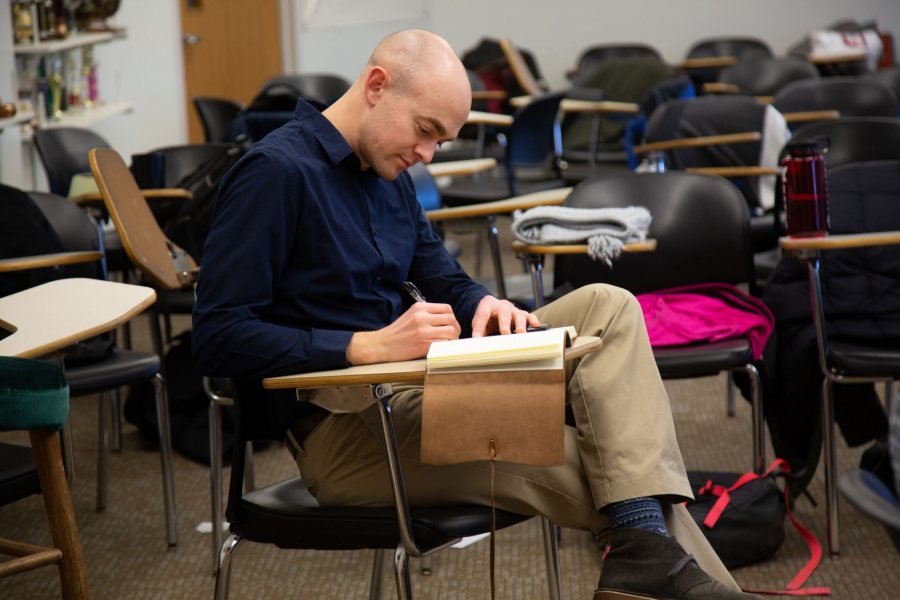

Andrew Jarboe ’05, a high school teacher at Match in Boston, takes notes during a January 2019 debate workshop at Bates, which Jarboe and the Brooks Quimby Debate Council set up for Match students. (Grace Link ’19/Bates College)

Students and parents shouldn’t put pressure on themselves to follow routines to the letter, Charles says.

“Do some reading and writing and math and then something fun, something creative,” Charles says. “Make Play-Doh. Plant some plants. Bake cookies. Find pockets of joy, and let those balance some of the frustrations and worries. Don’t be so stuck in routines that you get frustrated when they don’t get met.”

Both because of her district’s instructions and her own desire to provide as much leeway as possible, Kylie Martin has been giving her students two assignments a week on a pass/fail basis.

“Do some reading and writing and math and then something fun, something creative.”

“I’m passing students who make an honest effort to attempt the assignment, considering that many of them have so many barriers to remote learning,” she says. “I’m also emphasizing that they are resilient, and what resilience looks like during the pandemic: communicating with others about feelings, self-care, and giving the best effort to academics with what you have.”

Balancing classwork and serene moments is good for teachers, too, particularly those who are still students themselves.

Anita Charles is working with seven Bates seniors in the college’s teacher education program whose student-teaching placements have abruptly come to an end.

In lieu of being in the classroom, the students are observing videos of past classroom lessons, developing lesson plans, and welcoming “guests” to their Zoom classes, including Martin and Hong.

Because of Charles’ guidance, the students’ own work, and the Maine Department of Education’s flexibility, these students will still graduate from the program and be eligible for teacher certification. Charles thinks they might even have an advantage.

“I’ve been reminding them they’re going to be out there looking for jobs, and this draws on creativity, innovation, reflection, and problem solving,” she says. “They’re going to have some skills that employers will be looking for because they have gone through this.”

At every step, Charles says, teachers, students, and parents should do the same as everyone else whose lives have been disrupted: acknowledge what they’ve been able to achieve in trying circumstances, and cut themselves some slack when they need to.

“Teachers are doing extraordinary work right now,” she says. “The teachers that I know are truly missing their classrooms and their schoolchildren and are doing the very best they can to stay connected. Some are making personalized calls. Some are waving at kids from cars.”

At the same time, she says, “we need to be gentle on ourselves. We can’t do everything. We need to take small steps. Pay attention. Keep learning.”