March 11, 2020, saw a triple whammy of bad news.

Just during the evening, the NBA suspended its season; President Donald Trump issued an initially confusing order suspending some travel from Europe to the United States; and Tom Hanks announced that he and his wife, Rita Wilson, had contracted the coronavirus.

COVID-19, of course, was the backdrop to all this breaking news. And as the pandemic gained momentum at an exponential rate through the month of March, the week centered on Wednesday, the 11th, was when many Americans realized how fundamentally the disease would alter their daily lives.

The next day, Chris Danforth ’01, an applied mathematics professor at the University of Vermont, and his team saw that their “hedonometer,” an instrument that quantifies, in real time, national happiness based on millions of Twitter posts, had recorded a remarkable drop in mood — a low that lasted for the next several weeks amid the losses of jobs, freedom of movement, and loved ones.

“In the entire history of our instrument, over a decade, we’ve never seen an event that effectively persists in our collective mood for more than a day or two,” Danforth says. “Since March 12, the mood has been dramatically depressed on Twitter.”

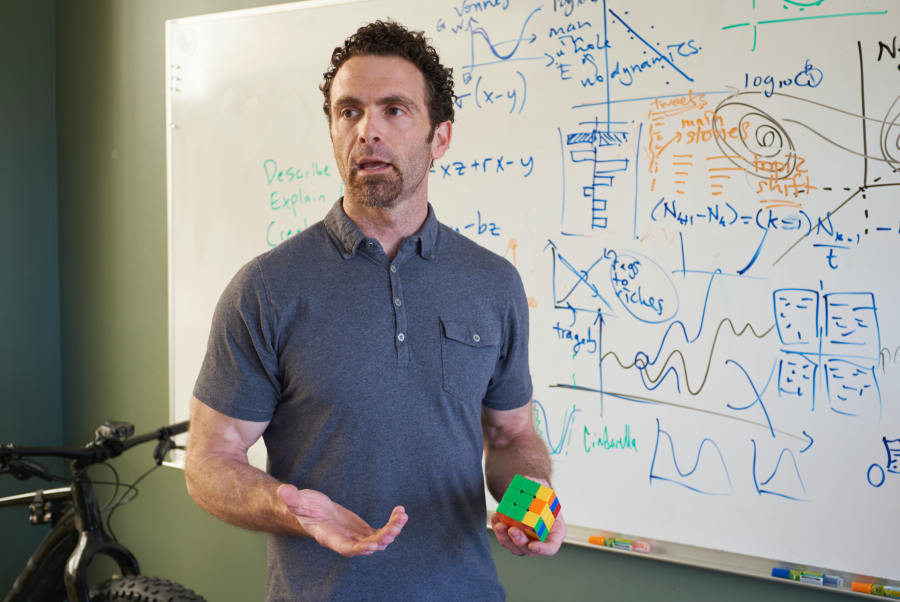

Chris Danforth ’01 directs the Computational Story Lab at the University of Vermont. (Courtesy of Chris Danforth)

Danforth, who directs the Computational Story Lab at Vermont, has spent his career finding out what social media — on a scale of millions of posts in dozens of languages and countries — can tell us about human emotion.

Using a different method from the hedonometer, he and social psychologist Andrew Reece ’01 have found that people suffering from depression post photos on Instagram whose colors are cooler and darker than those of non-depressed people.

And, in analyzing current data during the coronavirus pandemic, he’s also seeing evidence that his work analyzing social media might just identify viral outbreaks.

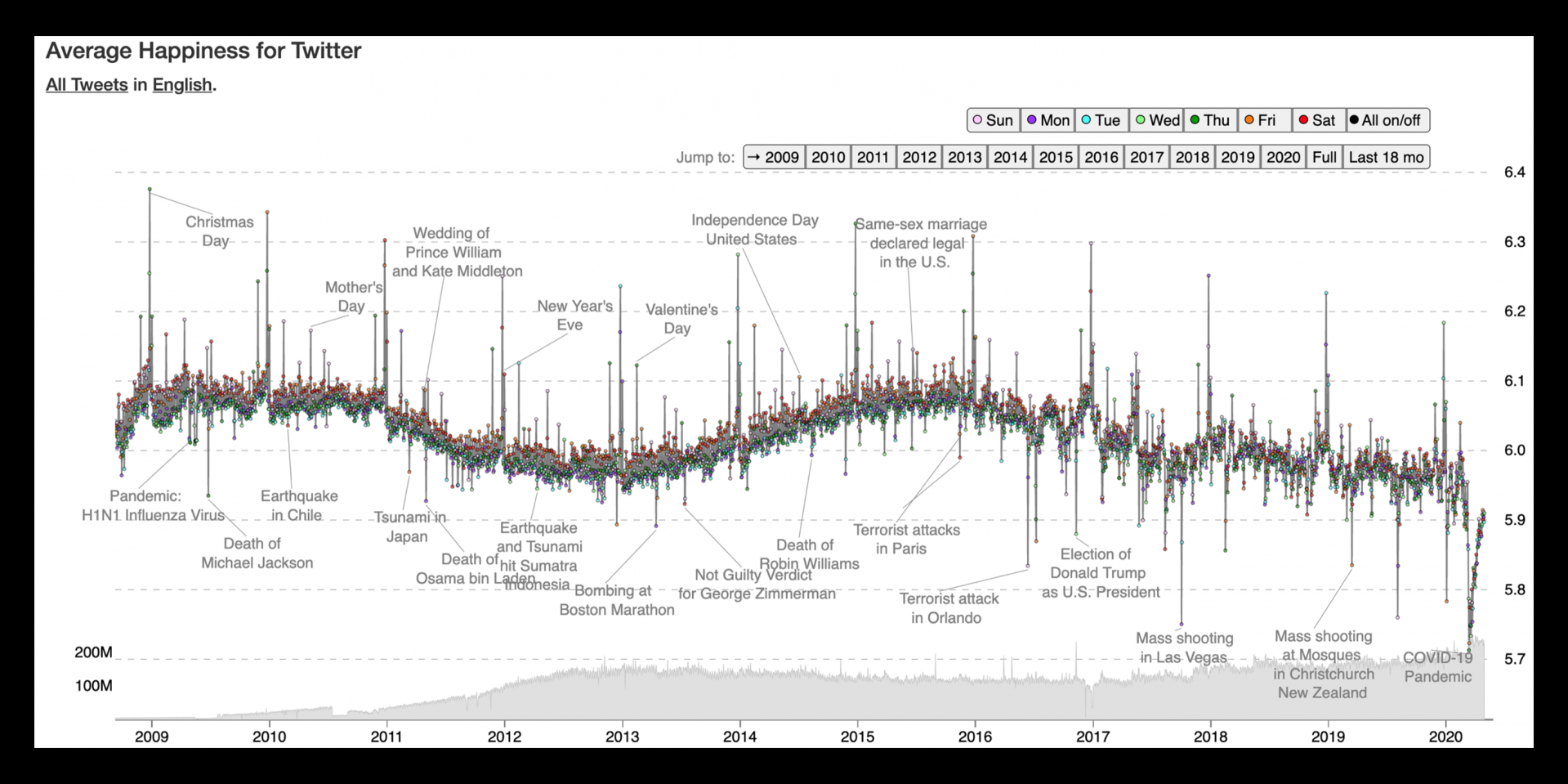

The hedonometer gauges mood primarily using Twitter, which Danforth says offers the most publicly available posts. Each day the software crunches about 50 million Tweets, 10% of the total number of posts on the site.

When they first created the hedonometer, Danforth and his team surveyed speakers of languages from English and Spanish to Indonesian and Arabic, asking them to rate thousands of words on a scale of happiest to saddest.

As a result, the hedonometer can take the words and phrases (and emojis) in each tweet, assign a value to them based on the mood they express, and average them together into a single measure of happiness, on Twitter, for that day.

This gargantuan graphic shows the average happiness on Twitter from the launch of the hedonometer in 2009 to the present day (each dot represents one day). Chris Danforth ’01 says the instrument has recorded more variability in mood since the 2016 presidential election. (Courtesy of Chris Danforth)

Hedonometer readings reveal patterns in the national consciousness and in daily life. In normal times in the United States, posts are happiest on the weekends and saddest on Tuesdays, Danforth says. Posts made in urban parks are as happy as those made on Christmas.

National moods as measured by the hedonometer hew to world events, at least some of the time, Danforth has found. Bad news — a school shooting, a celebrity death, a natural disaster — is associated with a drop in happiness, though only for about a day.

Using other instruments, Danforth’s team can also measure the amount of attention Twitter users pay to particular topics, like the coronavirus.

From this kind of analysis, it’s clear that attention doesn’t always follow the news, Danforth points out ruefully. Americans on Twitter were talking about the coronavirus a lot in January, when China was taking momentous steps to stop the spread in that country. That’s clear from the number of times Danforth’s instruments detected the word “virus.”

“Early March was a really hard time to be on Twitter when you’re a scientist.”

Then, attention “decayed” for about six weeks, Danforth says — people weren’t tweeting “virus” as much. It was during those six weeks that the coronavirus was blooming in the United States, as scientists at Northeastern demonstrated this month.

Danforth sees the silence on Twitter as a bellwether for how people, from John and Jane Doe up to top federal officials, were failing to notice the scale of the problem.

“Early March was a really hard time to be on Twitter when you’re a scientist,” Danforth says. “The world’s on fire, and nobody’s paying attention.”

“That’s what’s so diabolical about this particular virus,” he adds. “If you have one person testing positive simultaneously to 10,000 people having it, there’s no contact tracing to be done. The cat’s out of the bag.

“That six-week period will cost tens of thousands of people their lives because we didn’t respond soon enough. That decay in our attention was visible just in our use of the word ‘virus.’”

All this led up to that week of March 11, when the hedonometer measured a national mood that was the lowest in over a decade. And it has persisted — weeks of just Tuesdays, or a natural disaster every day.

This graph of late 2019 and the first months of 2020, each dot representing a day, shows how moods in the United States took an unprecedented nosedive after the coronavirus pandemic hit. (Courtesy of Chris Danforth)

“The Boston Marathon bombing in 2013 was one of the saddest days we’ve experienced,” Danforth says. “Our entire month has been below the day of the Boston Marathon bombing. That’s a pretty remarkable change in the daily content on Twitter.”

Danforth describes the hedonometer alternately as a “Dow Jones” and a “thermometer” for the national mood. But his team’s ability to analyze millions of Twitter posts might have an impact beyond that.

In identifying words related to coronavirus in various countries, Danforth noticed something curious. Countries in which, at a given point, there was a surge of descriptive words about the pandemic — words like “pandemic,” “coronavirus,” “WHO” — tended to see higher recorded COVID-19 case counts three weeks later.

Countries that didn’t have any uptick in virus-related language at that time didn’t have a later surge in COVID-19 cases. And once an outbreak had clearly taken hold in a country, people’s language shifted to phrases about responses to it: “social distancing,” “flatten,” “curve,” “lockdown,” “ventilators.”

“Human beings are really good at acclimating.”

In Italy, that surge in pre-virus tweets came in February. In the United States, in March.

It’s not clear why this correlation exists — why a country would be tweeting a lot about the coronavirus before testing makes clear that an outbreak has taken hold, or why a country with lower case counts wouldn’t be tweeting as much. But Danforth thinks that “this firehose of tweets” can help health officials identify outbreaks as they are happening.

“In places where there aren’t tests, you can use it to optimize and prioritize resources,” he says.

For Danforth, using the hedonometer and other instruments to measure emotion during the pandemic has reinforced one other aspect of human nature. Since moods on Twitter plummeted after March 12, they have been steadily rising again, even though they stayed well below average for weeks.

As April turns to May, the hedonometer’s readings have crept back up to “normal.”

“Who knows what’s going to happen?” Danforth says of the pandemic. But “human beings are really good at acclimating. The instrument is back to roughly where it was before.”