“It’s challenging to work with real people and real data on real problems in real time,” Adriana Salerno told one of her classes, in person, a seeming lifetime ago, back in February.

Salerno, associate professor of mathematics and department chair, was responding to a student’s concern about the class projects underway in “PIC Math: Topics in Industrial Mathematics,” a course Salerno launched this year.

The course is designed to give students real-world experience using mathematics in non-academic enterprises. Salerno’s class performed data-analysis projects for two nonprofit community partners, Lewiston Public Schools and Tri-County Mental Health Services.

During that February class session in Libbey Forum, one student wondered whether the students might actually be over-performing — making their deliverables needlessly elaborate or complicated.

Salerno was reassuring. She reminded the students that it’s her job to keep them on track. And besides, she said, the course was intended to teach not just data-analysis techniques but how to meet workplace realities — for instance, how to tailor products to meet a client’s need.

“This class is a bit like an internship” or a first job, she said. “Someone will say, ‘Well, we don’t know how to do this thing — can you do it?’ And there might not be a lot of guidance. You might just spend a lot of time spinning your wheels.

“Or you might work really hard — and then they’re like, ‘Oh, we didn’t really want that, we just wanted a pie chart.’”

“I’m an abstract mathematician. I don’t do applied mathematics. The course has been an interesting switch for me.”

Salerno’s course is the product of a professional development program offered by the Mathematical Association of America. The program, “Preparation for Industrial Careers in Mathematical Sciences,” aka “PIC Math,” helps schools better prepare students for non-academic career options in mathematical sciences. (The title uses “industrial” in a broad sense, e.g. “healthcare industry” or “real estate industry.”)

Math professors, Salerno explained after that class session, tend to be people who, like her, “went through academia and stayed in academia. We only know how to be students or professors, and don’t have a ton of interactions with business, industry, and government” — the so-called BIG sectors. “But the BIG careers are usually where our math majors go.”

“I’m an abstract mathematician,” added Salerno, who researches number theory. “I don’t do applied mathematics. The course has been an interesting switch for me.”

With support from a National Science Foundation grant, she attended a PIC workshop in summer 2019 to prepare for the course. Then, working with the Harward Center for Community Partnerships and the Center for Purposeful Work at Bates, she put together the 300-level “Topics in Industrial Mathematics.” (The course is cross-listed in the digital and computational studies program.)

“I learned how to best represent mathematical material to people who might not be as interested in the mathematics itself, but rather the end result.”

In hiring for math-centric positions, Salerno explained, employers look for facility with problem solving, communication skills, working in teams, and programming, in addition to the mathematical know-how. “Our math major gives them plenty of the math background and maybe even a bit of programming, but this is the first course where they actually do have to do all of these things at once.”

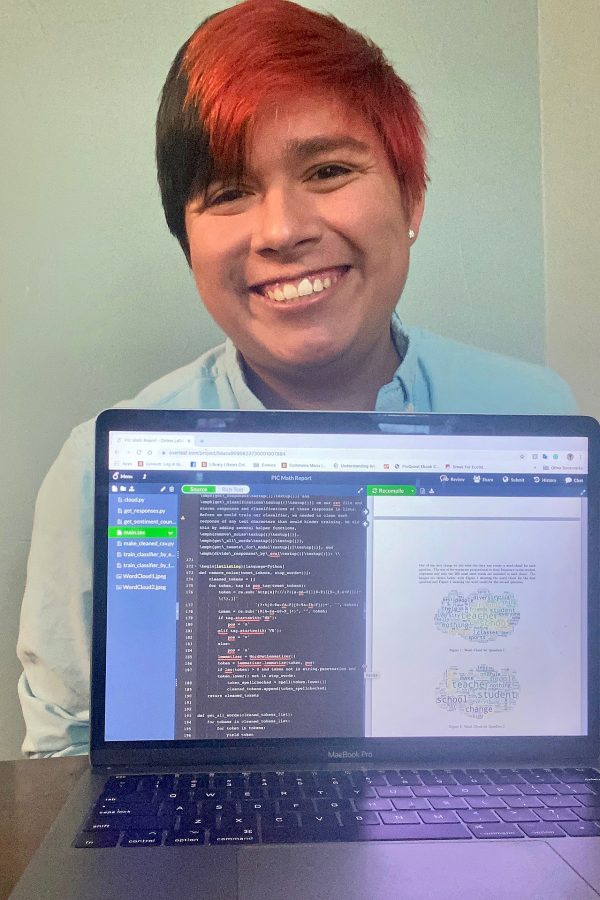

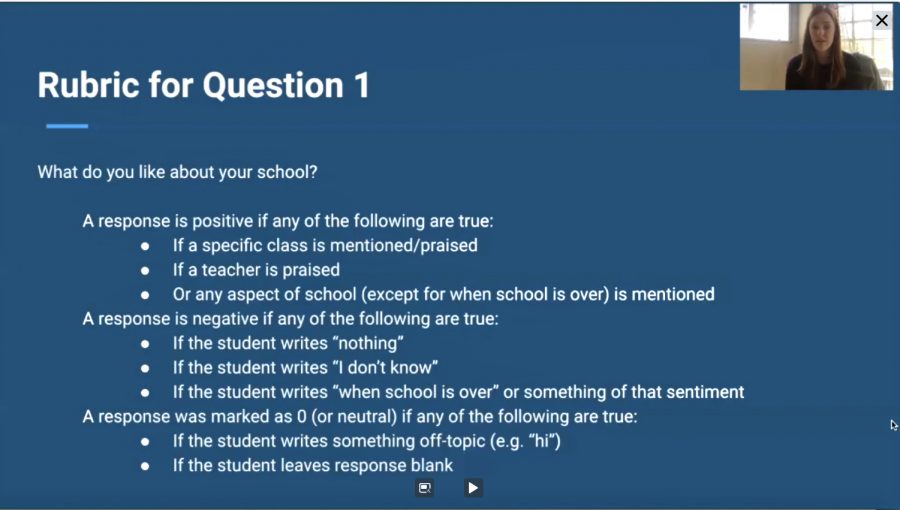

“Using the math skills that I have learned over my time at Bates on a real-world question was very rewarding,” says Jesus Carrera ’20, a math major from Waco, Texas. His team worked with the Lewiston school department, analyzing survey data to assess students’ sentiments about their particular schools.

“I was very surprised by how much I’d learn about real-world data science consultation. I learned how to best represent mathematical material to people who might not be as interested in the mathematics itself, but rather the end result.”

Divided into four teams, the 16 students in the course tackled several projects for Lewiston Public Schools and one for Tri-County, which provides treatment for mental health and substance abuse disorders. (And actually serves seven counties: The agency chose to stick with its known branding even as it expanded its service region.)

The school system sought help interpreting masses of existing data across a range of topics, from teacher workload to standardized-test scoring to student satisfaction at Lewiston High School. Tri-County, meanwhile, had just one question for the students to address: What proportion of people in need is the agency actually reaching within its service area?

Determining its market reach “was a particularly important activity” for Tri-County, said Chief Development Officer Jamie Owens, but the agency lacked staff time to take on the project.

As a starting point, the agency provided a spreadsheet of roughly 2,500 “de-identified patients,” a redacted list comprising only ages, zip codes, and presenting symptoms for each individual. From that data, the Bates team’s solution, in essence, was to build a model of patient profiles, cross-reference that with state and national data about the prevalence of specific disorders in Maine, and then correlate those findings with the zip codes across Tri-County’s service area.

“It’s likely that more people will have access to effective mental health services due to our work, and that’s an amazing feeling.”

After applying so-called Monte Carlo methods to constrain the potential for error, the Bates students projected that there are 285 potential new clients in nine towns in the seven counties, with totals ranging from 186 in Lewiston to one in West Farmington.

(Monte Carlo methods are computational algorithms that, in effect, apply random variables to test the accuracy of a mathematical process. The inventor, who was working on nuclear weapons at Los Alamos in the late 1940s, chose “Monte Carlo” as a project code name in honor of his gambling uncle.)

One of the things that surprised Owens the most about the students’ findings, she says, was the effect of distance on client engagement. As they build their provider networks, Owen explains, healthcare insurers assume that patients are willing to travel up to 25 miles to get to a care provider. But according to the students’ findings, that figure is really significantly less.

“We’re not drawing as many clients as I thought from the surrounding areas that we serve,” Owens explains. “The majority of the clients, when we look at where they reside by zip code, are really within 10 to 15 miles of our offices. In Lewiston, it’s even a little bit closer than that.

“I plan to use the findings to inform program development and how we can more effectively engage those in need of services who reside in really rural areas.”

“It’s likely that more people will have access to effective mental health services due to our work, and that’s an amazing feeling,” said a member of the Tri-County team, Jason Canaday ’20 of Wellesley, Mass., a double major in economics and math who’s interested in a career in statistics, data science, or mathematical modeling.

Tri-County has collaborated with Bates students on past projects, but this was Owens’ first. She has nothing but praise for the Bates team. “Very professional,” she says — “the critical thinking, attention to detail, and explaining the data points and why they’re important. Just very bright, which I would expect from Bates students.

“It shows me that they’re pretty well-prepared to go out and do what they choose to do” after Bates.

The four Bates teams tackled different projects, but encountered many of the same challenges — how to focus their research objectives, how to communicate their findings to a lay audience, whether they should serve those findings with a side of recommended action steps. (“We can give advice,” Salerno said.)

“I think, in the end, the most challenging part about these projects and about teaching this class was not the mathematics at all,” Salerno said.

To analyze data, “you really need just a few tools. It’s much more about cleaning the data, finding the right visualizations for the data, and, really, figuring out what the question is that you should be asking.”

Indeed, a major preoccupation for all the students was the nitty-gritty nature of real-world data. For instance, as the Tri-County team found, much of the publicly available mental-health data is about a decade old — a decade in which the prevalence of substance-abuse disorders, for instance, has increased dramatically. Data can also be incomplete, the product of a bad process, or encumbered by privacy concerns.

“I was surprised that a lot of working with data is monotonous,” said Canaday. “Unfortunately, searching for data sets, cleaning data, organizing data, and the like is the majority of time spent working on a project of this type.”

Still, “once our data were clean and run through the model, our group found it especially rewarding to see the results,” he said.

“Without my team, I wouldn’t have been able to do nearly as much, and I think this reflects the real world, where collaboration leads to success.”

In a more conventional math class, “when a professor gives you a problem, we’ve made sure that it’s doable, that the numbers are not too weird,” Salerno said. But in the new course, “I had no control over whether it was doable or not, so I definitely expected the students to be sort of challenged.”

But, she said, “I wasn’t expecting them to be so good at rolling with the punches. They’ve just been so adaptable, and so good at adjusting and reframing.”

Indeed, “one major takeaway from working in an occupational context is that teamwork is key,” says Ariel Lam ’20 of Oradell, N.J. A double major in math and sociology, Lam was a member of one of the Lewiston Public Schools teams. “Each person brought different talents to the group, making it possible for us to create a comprehensive final product.

“Without my team, I wouldn’t have been able to do nearly as much, and I think this reflects the real world, where collaboration leads to success.”