Each year we profile Bates seniors in a series known as “Voices of the Class.”

Here are the five we profiled from the Class of 2020, each one produced by Theophil Syslo:

- Sam Findlen-Golden talks about how mathematics manages to “work its way into a lot of places that I didn’t expect.”

- Maddie Hallowell explains how she honed her data-collection skills — which she employs in fisheries research — by sending balloons high into the sky.

- A poet, Jesse Saffeir offers insights into the verses she wrote about unexpected places: Maine’s power-line corridors.

- A first-generation college student, Ryan Lizanecz talks about the slow process of finally feeling comfortable at Bates.

- Topher Castaneda, a front-line Residence Life staff member, describes his love of creating community at Bates.

Sam Findlen-Golden ’20 and the unexpected joy of mathematics

When Sam Findlen-Golden ’20 of Amherst, Mass., first started at Bates, he wanted to try anything and everything that was available to him. “Just because it’s an option,” he says.

Since then, as he’s learned more about what interests him, he’s let go of some pursuits while taking a deeper dive into others — including both mathematics and the performing arts.

A mathematics major and French minor, he’s a member of the a cappella group Crosstones and the music director of the Robinson Players, the student theater company.

Video by Theophil Syslo.

For Findlen-Golden, math serves as an organizing principle in his life. “Math manages to work its way into a lot of places that I didn’t expect,” he says. “It can be math in the perspective of music or through the perspective of history and education, which is a lot of what I’ve done here outside of academics.”

He’s served as a peer tutor in the Mathematics and Statistics Workshop and, through the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, helped to organize volunteer tutors for high school–aged English language learners at Lewiston Public Library.

As he completes his math major, Findlen-Golden has similarly dived deep into biomathematics, learning how best to model the spread of diseases. Along the way, he’s learned how to embrace the more subjective side of his discipline.

Sam Findlen-Golden ’20 (left) and El Khansaa Kaddioui ’20 of Elhajeb, Morocco, talk with Associate Professor of Mathematics Meredith Greer during their biomathematics seminar in Hathorn Hall. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

“I’ve always been a very pure mathematician: I like working with straight numbers,” he explains. In the past, “whenever it gets into interpretability, like modeling complex behaviors or patterns in nature, I’ve always been a little intimidated because as much as I enjoy being creative, I also like things that have objective truth to them. There’s a bit of a simplicity in that.”

Yet once again, math has shown him a path, and he’s discovering new satisfaction as he’s explored biomathematics in his senior year, including epidemiology and disease spread.

“It’s shown me that there can be this beautiful blend of interpretability and subjectivity to something that is very objective. You have this objective language to describe subjective opinions and subjective patterns that can be modeled, interpreted in various ways.”

Maddie Hallowell ’20 and the lows and highs of data collection

Maddie Hallowell ’20 grew up in North Haven, Maine, an island community in Penobscot Bay. For her family and neighbors, the effects of climate change are immediate.

“I recognize the changes that are happening in the coastal system and the ecosystem,” she says.

With the guidance of Bates professors, Hallowell discovered the value of data collection, primarily through sensors deployed along the coast. She designed an interdisciplinary major incorporating digital and computational studies and geology, and her senior thesis involves developing a sensor that can be attached to lobster traps.

“I want there to be a future for where I live and for there to be a place that I can come back to when I’m older,” Hallowell says. “I think that getting this information will help solidify my ability to do that.”

To expand and hone her abilities, Hallowell has devoted her extracurricular time to collecting data in another direction — straight up — with the High Altitude Ballooning Club.

Video by Theophil Syslo.

For a recent launch, club president Hallowell and the rest of the student team rose at 5 a.m. to drive to New Hampshire, where they launched a balloon filled with 200 cubic feet of helium dozens of miles into the atmosphere.

When the team retrieved the balloon two hours later in central Maine, along with sensors that measured things like temperature, pressure, and humidity, “it felt like we had done something really big,” Hallowell says.

“Data collecting really excites me,” she adds. “You expect what you’re going to see, and then you can get a whole new frame of information, and it can completely change what you thought.”

Maddie Hallowell ’19 of North Haven, Maine, fills a high-altitude balloon with helium before a launch on Nov. 9, 2019. (Theophil Syslo/Bates College)

Jesse Saffeir ’20 and lines of poetry sparked by lines through nature

One of the most important lessons Jesse Saffeir ’20 of Pownal, Maine, has learned at Bates is the importance of applying what she learns in class to her own life in the world.

“What impact do we have on other people, and how can we move through spaces in ways that make people feel comfortable and included?” she says.

An environmental studies major, Saffeir began to think about how she moves through one type of space in particular: Maine’s power line corridors. The corridors, cut through fields and forests to make way for tall towers and wires, are juxtapositions of what we think of as manmade and natural — if we think about power lines at all.

“We all, for the most part, rely on electricity to live, and we never really encounter the spaces where that energy is produced and transported,” Saffeir says.

Video by Theophil Syslo.

So last summer, Saffeir walked along the corridors, funded by a Bates Otis Fellowship, which supports students investigating relationships between humans and nature. She defined the experience more as bushwhacking than hiking — since there are no trails, she had to make her own maps and plan where to get her food.

“I think we often forget just how much we rely on the spaces around us for our well-being and our sanity,” she says.

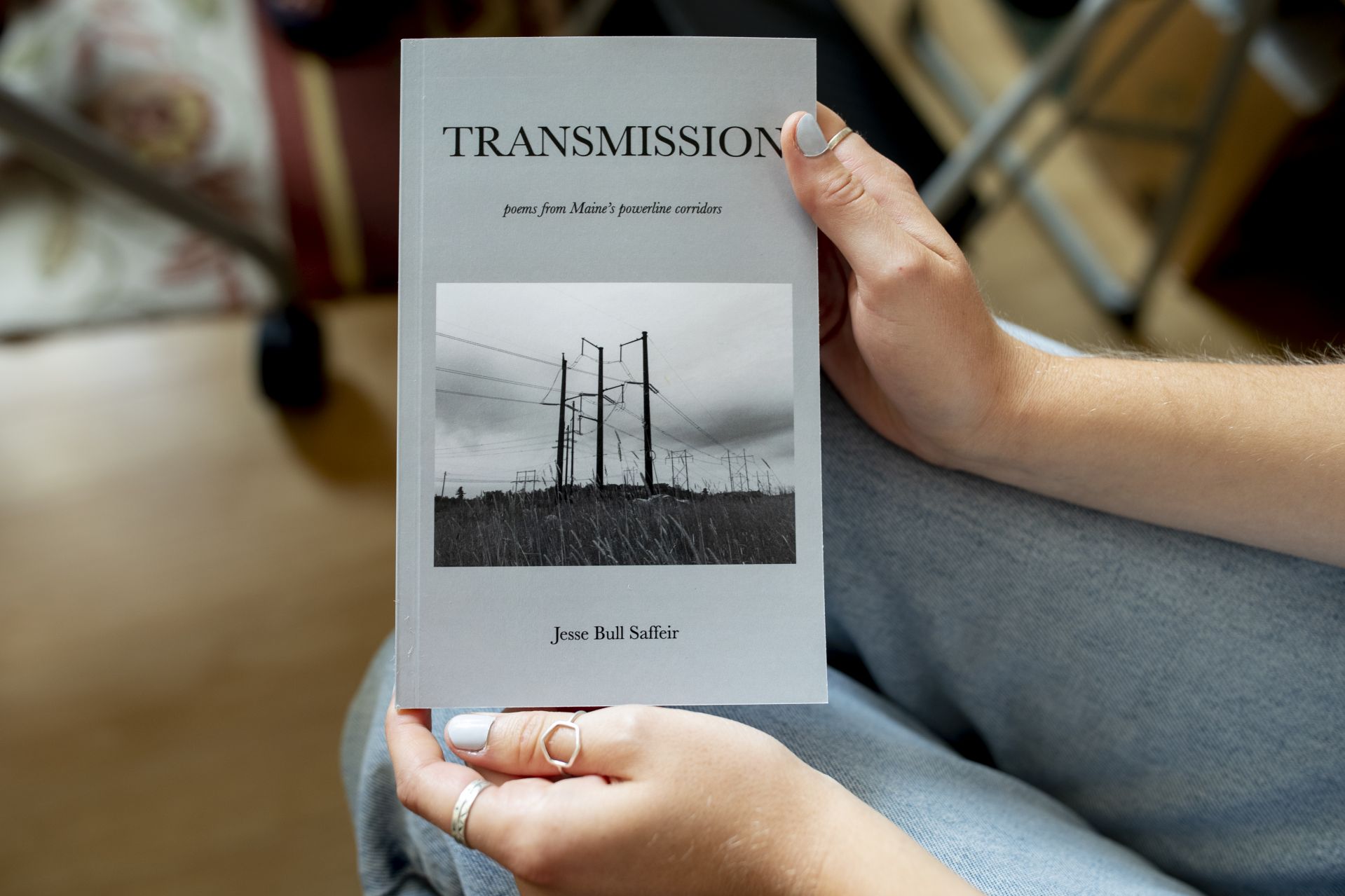

Saffeir wrote a poem each day as she walked, later collecting them into a book called Transmission: Poems from Maine’s Powerline Corridors.

Jesse Bull Saffeir ’20 of Pownal, Maine, displays her book of original poetry about Maine’s power line corridors, written during an Otis Fellowship sojourn. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Walking the lines, Saffeir says, has reinforced and given deeper meaning to what she has learned in her classes: that the environment isn’t just the wilderness, that there’s no clear binary between “human” and “nature.”

“I want to think a little bit broadly about our environments as being the places where we live, where we work, where we play, and also the environments that we rely on but don’t really spent a lot of time in,” she says.

“Being able to apply the things that we’re learning about in a very direct way to our own lives is so important to just becoming humans in this world.”

Here is one of the poems from Transmission:

“Transmission”

I step into the lake to fill

an empty jug with cool clear water.

I cannot trust my senses

so I heat it to a boil.

I am learning to shelter

my body

to only drink upstream

of the runoff —

pass by the green water

the brown water

the turquoise water pooling

near the mines

sooner or later everyone

gets thirsty

the world is not a disease

that I know of.

it is an inheritance beyond

my wildest dreams.

at night the space between my eyes crawls

with deer ticks, vectors that will burrow

their bodies into me transmitting

a fear I cannot see.

I walk along transmission

lines. the air grows charged

condenses to a static spark

each time I touch a finger to metal

and what that spark contains

has travelled a long way to get here

and will keep traveling

long after it passes

Ryan Lizanecz ’20 finds a home at Bates as a Maine first-gen student

When Ryan Lizanecz ’20 first came to Bates, “I was anxious, I was curious, I was scared,” he says. “Literally every feeling I could possibly feel at the same time.”

Lizanecz is from Portland, Maine, and he is the first in his family to go to college. Maine as a whole and Bates are similar, he says, in that both are “small communities where people know each other and people are friendly.”

Nevertheless, arriving on campus was an “information overload.” Lizanecz had lived in the same house all his life and never been away from his family for more than a week.

At night early in his Bates career, he says, he often dreamed of home.

Video by Theophil Syslo

“Thankfully,” he says, “Bobcat First! was my foothold.” The four-year program designed to foster belonging among first-generation-to-college students “provided me with everything I needed to succeed in the first year–plus of my college experience. They were really a family to me.”

With that support, Lizanecz flourished. A politics major, he has delved into the ways that structures of power shape the world.

“Bates does a very good job, especially in the liberal arts, of teaching you about how all these different moving parts of the world are interconnected, and how that impacts how the world works,” he says.

At Opening Convocation on Sept. 3, Ryan Lizanecz ’20 (center) sits between keynote speaker and honorand Dolores Huerta and Phillips Professor of Economics Michael Murray. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Lizanecz has sung with the Deansmen, the oldest of Bates a cappella ensembles, throughout college. He is also the president of student government this year; in that role, at Opening Convocation, he told the incoming first-year students that their Bates experience will be what they make of it.

Now, when he spends the night at home in Portland, Lizanecz dreams of Bates.

“Bates is my home,” he says. “This is where my friends are. This is where I have the most fun. This is where I learn things that I care about. I think that that’s what Bates has become to me.”

Topher Castaneda ’20 builds community as a Residence Life leader

“Something that I’ve realized I truly enjoy doing is building community,” says Topher Castaneda ’20 of Los Angeles.

Which makes Castaneda a great fit among the front-line community builders at Bates, the college’s Residence Life staff.

This year, Castaneda is a Residence Coordinator team leader. He’s in charge of six Junior Advisors who, in turn, work with groups of first-years in their residences known as First Year Centers. He has three first-year residences in his portfolio: Clason House, Milliken House, and Frye House.

Video by Theophil Syslo

“Being so far away from home, I’ve found ways and places to help structure some sort of community around myself, but also around other people who identify as me,“ says Castaneda.

“I’m first-gen, I’m queer, and I’m Latinx. How do I build community for those people, but include more stories in the narrative? One really good way is through Res Life.”

“A really big thing when building community is making sure that people feel heard.”

Castaneda taps into a powerful and fundamental way to forge community: “Stories are really important because they connect people,“ he explains.

“A really big thing when building community is making sure that people feel heard, and people are also understanding where you’re coming from — what your background is, your culture, and what your norm is.”

His Res Life work “has been just awesome,” says Castaneda. And that’s partly because, again, of the human connections. “You get to meet so many different people that you wouldn’t otherwise get to meet at Bates.”

An environmental studies major, Castaneda devoted his summer to supporting community in a different way. Working with Holly Ewing, Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, he collected water samples from the local municipal water source, Lake Auburn, as part of research into protecting drinking water quality for the Twin Cities.

Topher Castaneda ’20 (right) sits on a boat with Holly Ewing, Christian A. Johnson Professor of Interdisciplinary Studies, as they do fieldwork on Lake Auburn. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)