Each week this fall, we’ll introduce new Bates professors who have tenure-track positions on the faculty.

This year’s nine tenure appointments are in the disciplines of art and visual culture, classical and medieval studies, economics, English, environmental studies, dance, politics (two appointments), and psychology.

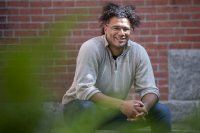

This week we introduce the fifth of our nine new faculty members, Lisa Gilson

Name: Lisa Gilson

Title: Assistant Professor of Politics

Degrees from: Yale University, Ph.D and M.A. in political science; Tufts University, B.A. in political science

Before Bates: Postdoctoral fellow in social studies, Harvard University

Her work: Gilson focuses on political reactions expressed outside of mainstream political channels, from abolitionist movements to contemporary far-right groups.

A political theorist, she is working on a book about the relationship between such social movements and social critics, including artists and writers, and the idea that the various political actors involved in a movement “are each doing particular kinds of things. Each has strengths that are particular to what kind of organizing they’re doing and what kind of protest they are doing.”

Example 1: In one chapter of her book, Gilson looks at Walt Whitman. While his writings were sympathetic to egalitarian and anti-racist ideas, his work didn’t actively call out racists and Southern sympathizers.

Yet, as Gilson argues, political actors like Whitman must be viewed in context. Whitman was uniquely situated to speak to a particular audience — Southern whites — that otherwise would have been “disgusted by, or not respond well to, a broader anti-racist movement. He spent a lot of time really trying to target that audience and work with that audience.”

Meanwhile, other actors in the movement, including Radical Reconstructionists, “were facing other kinds of demands. They couldn’t speak directly to white Southerners because the white Southerners obviously had no interest in listening to them.”

Example 2: Gilson pointed to recent Twitter comments from U.S. Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez responding to critics who said that Black Lives Matter activists’ language around defunding the police doesn’t play well among voters.

“We shouldn’t be attacking people for playing a role that is adapted to their specific situation.”

AOC’s response, in effect, sums up Gilson’s book project. “Activists who are trying to get people out into the streets will use language that might not poll well with the broader voting public. But it’s not the activists’ job — nor would it play to their strengths — to use language that polls well.”

While elected officials have to think about what language they use to further their goals, activists “use the language that works best for their specific and immediate goals,” she says. “For example, the slogan ‘defund the police’ may appeal more to people who actually show up at protests rather than those who don’t participate. And that’s fine. We shouldn’t be attacking people for playing a role that is adapted to their specific situation.”

Ideas in the classroom: Gilson is teaching “Politics and Literature” this fall, looking at how writers target “different audiences with work that’s outside of what is traditionally considered to be ‘political.’” For example, the class will read, among other works, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye, which raises questions about race, class, and gender through its depiction of a young Black girl who believes that her dark skin makes her ugly.

Working outside traditional political spheres, writers like Morrison seek to “change our broader culture and the broader discourse that people have around certain topics.”

Finding her path: Gilson grew up in a diverse area and says she quickly learned that her experiences as a white person were fundamentally different from those of her Black neighbors.

In school, “I started connecting my experiences growing up and being in a more racially diverse neighborhood and being treated better, and not having to think about my skin color, and how that related to my interactions with the police” with a broader system of racist oppression — one she wanted to study and fight.

Sample lesson: Gilson often teaches introductory courses in political theory. In one class, after having her students read the works of theorists like Hobbes, Rousseau, and Marx, she gave them Politics of Piety, by Saba Mahmood, a book that analyzed a women’s piety movement in Cairo.

“The women who are in this piety movement are choosing these religious precepts which place them in submission to their husbands,” Gilson says. “Mahmood makes a complicated argument that the women are expressing a type of agency.

“It’s one of my favorite things that I’ve ever taught because it’s challenging to me, and because the students themselves have to take a step back and ask, ‘What does it mean to say that I support a position that [they wouldn’t naturally agree with?]”

Why Bates? Gilson’s undergraduate college was Tufts, where programs such as the Experimental College Tisch College of Civic Life informed her belief that there were “things that you could do as a scholar that also would contribute to the community,” Gilson says.

During her job search, the “importance of community-engaged learning was one of the first things that I noticed about Bates,” she says, finding the college’s approach — forging long-term relationships with community partners — preferable to the drop-in model of community work, where students do a few projects, write their papers about it, and then graduate.

“If you’re really interested in your community, shouldn’t you be thinking about the long-term needs of the community? About how the community has already tried to organize around those needs? And how might you be able to support what exists already?”