When Kama Boswell ’23 of Seattle, Wash., came to Bates last year, the culture shock of moving across the country was eased by the Junior Advisor in her residence.

Inspired by her experience, last winter Boswell applied to be a Junior Advisor for fall 2020 to help another new group of first-years discover their own “home away from home.”

Boswell envisioned doing what her JA in Rand Hall had done for her: sharing meals with first-year students, planning movie nights in common rooms, throwing ice cream parties, and having one-on-one “cat chats” to make sure the daunting process of settling in at college wasn’t too overwhelming.

But what she didn’t expect when she happily accepted the job was how COVID-19 protocols would make her role that much more challenging. How she’d be tasked with creating a community for 14 new Bates students who could not go into other residence halls, hang out with more than 10 people at a time, or even leave their bedrooms without their masks on.

Boswell is one of about five dozen or so Junior Advisors and Residence Coordinators who live and work with students in the college’s 30 residences, ranging from large halls like Wentworth Adams Hall (which sleeps 175 students) to tiny wood-frame houses around campus, like Stillman House on Wood Street, which is home to just seven students.

Usually older students, Residence Coordinators focus on the living experiences of sophomores, juniors and seniors. JAs, on the other hand, live and work closely with groups of 12 to 20 new students in what are called First Year Centers.

Trained extensively by the Office of Student Affairs, JAs (the word “junior” refers to their paraprofessional status, not class year), they are mentors, guides, role models, and organizers who “help connect students, especially first-years, to the Bates experience in whatever way is authentic to them,” says Assistant Director of Residence Life Eddie Szeman.

Even in a normal year, it’s “a really tall order,” he says, “when you get a group of 12 first-year students from across the country, to find a way to authentically welcome each of them.”

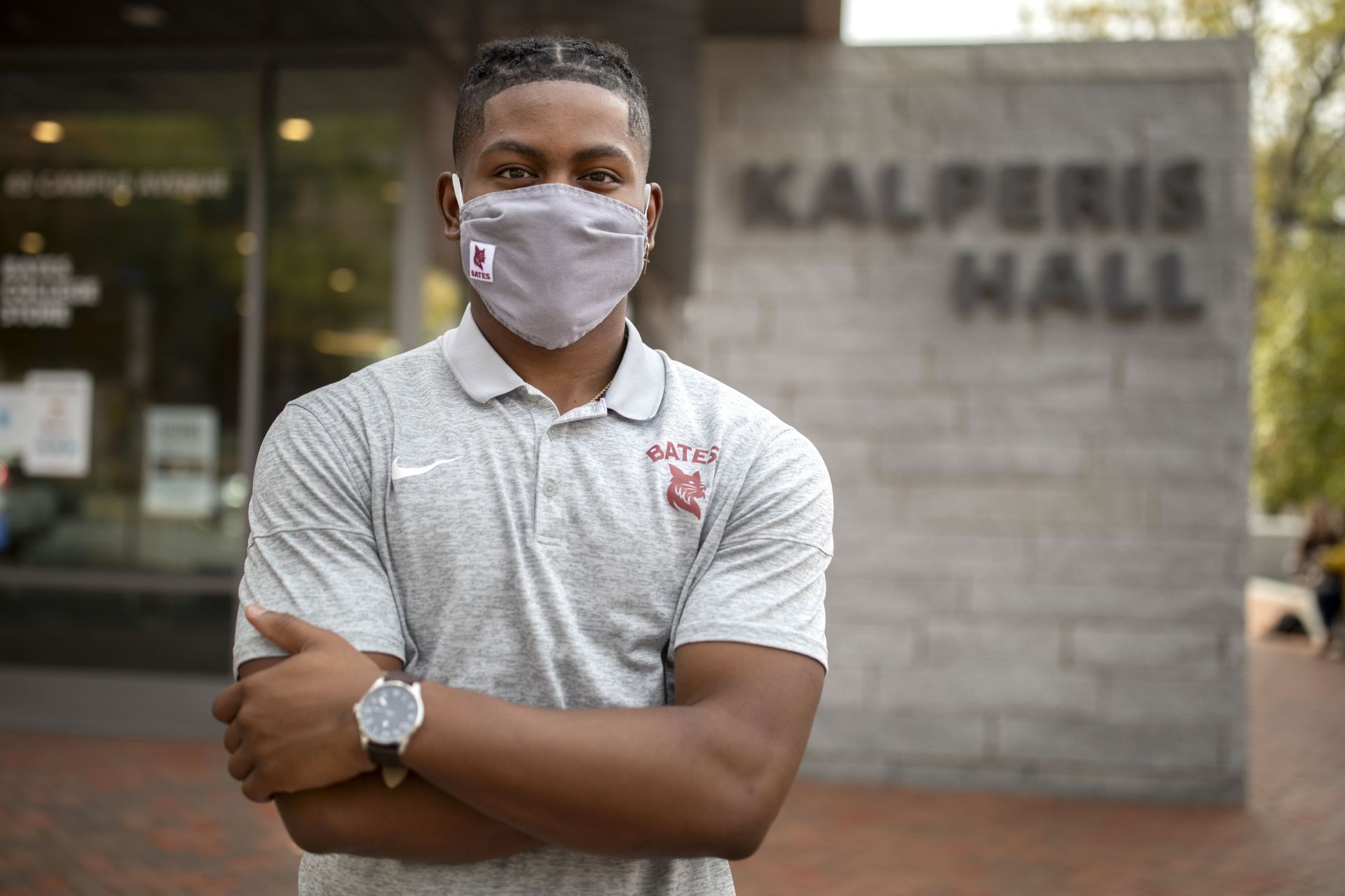

As a JA in Kalperis Hall, Ken Williams ’23 of Phenix City, Ala., is trying to deliver that tall order. Before an interview, he’d just finished a protocol-compliant event with his 14 first-year students, a game where each student, armed with their own chalkboard, created designs based on categories that Williams and other JAs came up with.

It’s a deceptively simple activity: “a way for first-year students to get to know each other through their artwork and creativity.”

Like many of us who are learning to navigate our lives during a pandemic, Williams has developed his coping strategies as a Bates JA. “COVID has only altered the space,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that you can’t make friends or try new things. It’s just that the way you approach those things is different.”

Still, the residence protocols add another layer of responsibility and, at times, stress to the work of these JAs. Sometimes, Williams says he wishes he could just focus on schoolwork. Then he thinks about his first-year students. “I keep my head above water by thinking of how I can support my students. I feel like I’m experiencing my first year again but in another light.”

He says he and other student Residence Life staff members feel well-supported by the older Residence Coordinators and the college’s professional staff. “From those different levels you can receive different amounts of support,” he explains. “If I ever have a problem, I can send a text over to my RC or knock on her door. I know she’s there if I need her.”

And he knows he can stop by Szeman’s office any time. “It’s nice to be able to chat for an extended period of time and know that a person is there and I can stop by whenever I want to openly communicate.”

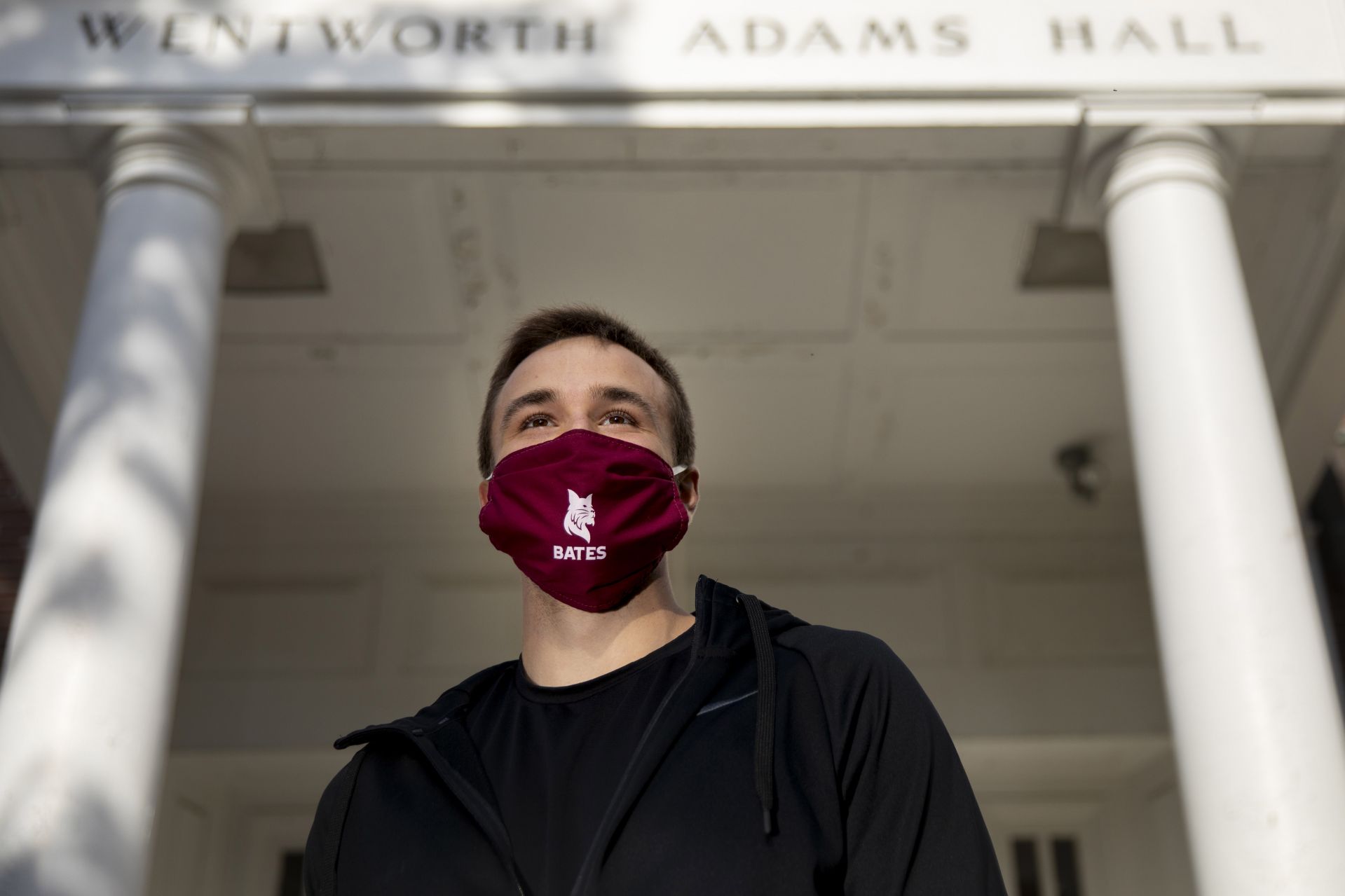

Four weeks into an unprecedented fall semester, “there still are similarities to last year,” says Jared O’Hare ’23 of Middletown, Conn., a JA in Adams Hall. “There are still key pillars that we have to focus on to make sure kids can transition smoothly. But there are things I never could have envisioned having to do.”

That includes trying to hold most programs outside since the college’s physical distancing protocols — 6 feet apart nearly all the time — makes it difficult to host indoor events with everyone in attendance. (Campuswide, indoor events are limited to 50 persons, and no food is allowed.)

Thanks to warm and mostly dry weather, O’Hare’s First-Year Center has been able to eat meals outside, often in the now-popular Adirondack chairs around campus. And there are time-tested bonding activities that he and other JAs can offer, such as the traditional walk to Dairy Joy for ice cream.

While the roles of JA and RC are non-punitive, meaning they do not enact disciplinary measures, they do have broad responsibility for upholding community standards. The same goes for COVID protocols. JAs and RCs are there to help uphold the guidance, but not take names.

“I was relieved to find out it wouldn’t be our job to micromanage our students because that would tarnish relationships more than help them come closer together,” says Boswell, a JA in Page Hall. “But if you see people breaking the rules you can’t just be OK with it.”

On their own, this fall’s JAs and RCs have developed a kind of bystander-intervention approach to helping students follow COVID protocols. “It’s trying to get at how peers and other students can respond when they see folks who are not acting out public health behaviors that we know are important, what to do when they see folks taking risks that put other people into risk,” says Szeman.

“This goes back to the RCs and JAs being a mission-driven group,” adds Molly Newton ’11, associate dean of students for residence life and health education. “What they’re not saying is, ‘Hey, this is the rule. You have to follow it.’ They’re saying, ‘What’s our goal here?’ And the answer is, ‘To be able to stay here.’”

Returning students who lived through everyone going home in March are particularly invested in staying, she says, and first-years who experienced the shutdown in their high schools know it too. “So it’s not about writing someone up or calling security, it’s about working towards the common goals that are underlying everyone’s experience here.”

In Page, Boswell’s first-years have luckily settled into their new routine without any hitches. “They get along with each other really well,” she says. So far, her programming has included communal picnic-style meals outside Commons to get to know each other and one-on-one games of Battleship between Boswell and each of her students. (Battleship is, she insists, the best board game ever.)

Besides offering programs to help their students bond, JAs are also charged with passing along Bates lore, knowledge about activities, and what the coming year will bring. Here again, these sophomores are at another COVID-caused disadvantage: They’ve never experienced a full Bates year.

For example, says Boswell, “I feel kind of lacking when first-years ask me about Short Term. I don’t know what Short Term is like because I haven’t been here for one. I can wishfully tell them that I think it’s really fun.”

Looking ahead, she plans to make her first-years Halloween-themed self-care kits “as a final push to get through the module.” (This fall, the semester is broken into two 7.5-week “modules,” in which students take two classes for more time each week, rather than four courses for a semester. The change effectively de-densifies academic buildings.)

Boswell’s Battleship example typifies a type of activity, very much one-on-one, that suggests that there are different ways for a student to be an excellent JA or RC, says Newton. For years, a key JA requirement has been to offer programs — from laser tag to orchard trips — for their First-Year Centers. Students who were good at presenting these programs were often deemed to be excellent JAs.

“Some people’s skill sets really shine in those marquee programs that everyone loves,” says Newton. “But it’s not everyone’s skill set.” Now that larger events aren’t possible, the value of other interpersonal skills among JAs — ones perhaps more associated with introversion — are coming to the fore, says Newton.

Those include “being comfortable creating spaces for deeper conversations, and being comfortable in silence during those moments. Those moments are unlikely to happen during laser tag, but more likely when you go around knocking on doors and checking in with your first-years.”

All of this “has implications for racial justice,” says Newton, who notes that residence life, as a professional field, skews white and female.

It’s all about having different strategies for helping students “feel like they belong here, and to catch those challenging things that come up sometimes around mental health or negative outcomes associated with not feeling like you belong,” Newton says.

Pandemic or not, the Residence Life program at Bates has been recognizing leadership skills among JAs and RCs that go beyond programming ability. “It’s something we’ve been working on for a long time,” Newton says. “It’s given us more diversity in the types of ways that you can be a good JA.”

All of this “has implications for racial justice,” says Newton, who notes that residence life, as a professional field, skews white and female, as do some of the student-life events often depicted in marketing materials, like apple orchard trips or spa night. Valuing different ways to lead, program, and mentor “is critical to how we engage men and how we engage in recruiting people of color. And we’ve been really lucky that our students have jumped at those opportunities and done such a great job.”

While larger residences like Page or Parker halls can have multiple First-year Centers, the smaller, wood-frame houses on and around Frye Street might have just one. That’s the case at Stillman House, where Ali Manning ’23 of Sydney, Australia, is a JA.

Unlike her peers in larger residences, Manning’s First-Year Center in Stillman House, the college’s substance-free residential living center, numbers just seven students — the total number of students in the entire house. With so few students, “we are interacting more than most First-Year Centers,” says Manning.

So far, Manning and her students have watched a lot of movies together (“whatever’s on Netflix or Disney Plus,” she says) and have had organized game nights. With so few people in one house, the First-Year Center can easily hold indoor events with enough room for everyone to socially distance.

Like Boswell, she feels somewhat ill-equipped by not being able to tell first-year students what a full Bates year is like. “The thing that makes me feel better is that everyone is in the same boat,” she says. “It’s not like I’m the only one who’s had a warped sense of my first year at college. I also think that as sophomores who haven’t exactly had the perfect year of college, it’s a really good lens to be able to help first-year students through.”

For these JAs, it’s more than fun and games. For example, much of this year’s Orientation was delivered to first-years online, including an introduction to the college’s Green Dot program, which empowers bystanders to intervene in potentially violent situations.

“We knew how important these discussions are and how they impacted us when we first came to campus,” says Evan Ma ’23 of North Attleboro, Mass., a JA in Parker. “But we observed how when you do this stuff online, it’s sometimes easy to just click the right answers and move on.”

To reinforce the online introduction, Ma and two fellow JAs developed real-life scenarios that fellow JAs could use to teach their first-years how to intervene when they witnessed social interactions that looked unsafe. “They all thought it was a necessary conversation that we needed, and they all thought it went great,” says Ma. “I was very happy.”

Despite the newness and uncertainty of fall semester, the JAs agree that their first-years are making the most out of the unusual circumstances. “They’ve all really taken it in stride,” says O’Hare, who is now trying to come up with programs for when cold weather forces his first-year center to socialize indoors. “I can imagine if I was a first-year I’d be really frustrated, but they seem to all be doing really well managing the situation.”

Maeve McSloy ’24 of Old Greenwich, Conn., says that despite COVID regulations, she’s still found a sense of community in her center with the help of her JA.

“She’s been so nice and bubbly, which is really important when you’re coming into a new situation,” she says. A resident of Parker, McSloy also appreciates that her JA prioritizes her students’ safety but isn’t “out to get anyone in trouble.”

“As an institution, we owe a debt of gratitude to them for carrying forward a student experience at a time when it’s harder than ever.”

As they continue to make their first-year students’ homes away from home as inviting as they can, one of the biggest rewards for the JAs is witnessing a community being built.

“Seeing my first-year students hanging out together around campus really warms my heart,” says Boswell. “I feel like I had some sort of piece in helping that connection happen.”

And it’s not going unnoticed. “As an institution, we owe a debt of gratitude to them for carrying forward a student experience at a time when it’s harder than ever,” says Newton.

“We all think about the positive side of building community and how great it feels. But sometimes community can feel really bad. In both ways, this year’s JAs and RCs are in it with each other more so than ever before.”