Each week this fall, we’ll introduce new Bates professors who have tenure-track positions on the faculty.

This year’s nine tenure appointments are in the disciplines of art and visual culture, classical and medieval studies, economics, English, environmental studies, dance, politics (two appointments), and psychology.

This week we introduce the ninth of our nine new faculty members, Michael Boyd Roman.

Name: Michael Boyd Roman

Title: Lecturer in Art and Visual Culture and Mellon Postdoctoral Fellow

Degrees from: California State University, Northridge, M.F.A. in drawing; Maryland Institute College of Art, M.A. in community arts; Syracuse University, B.F.A. in painting

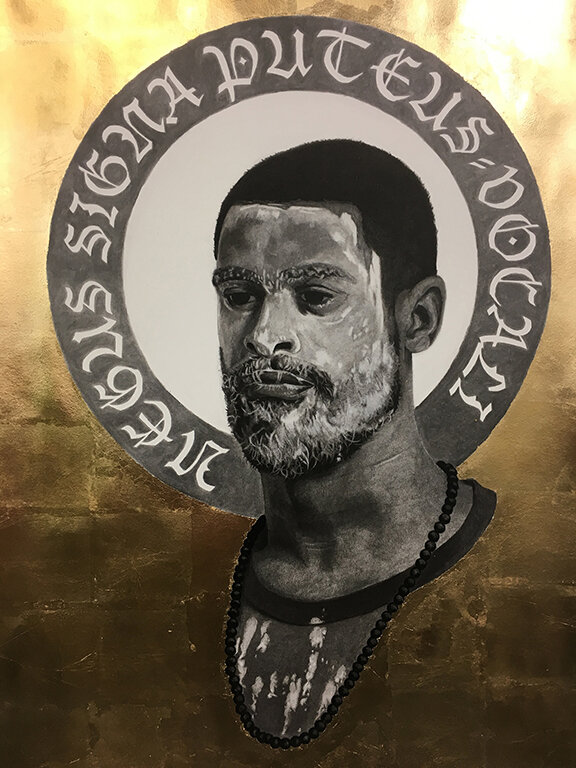

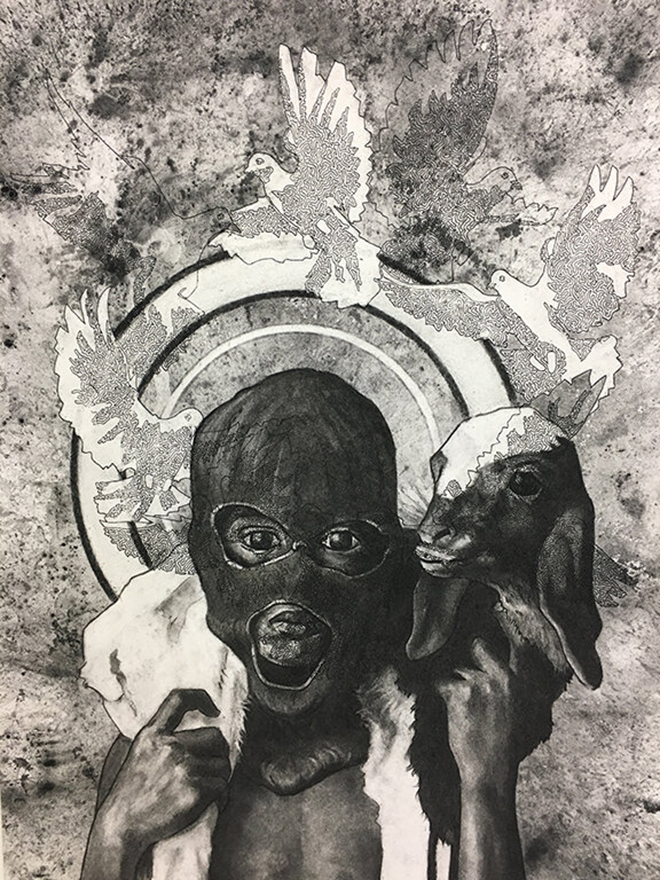

His work: Through drawing, installation, and digital media, Roman seeks to “portray the ordinary grace of contemporary Black men.” His works blend elements from hip-hop and urban culture with references to art history and religious iconography, especially from the Renaissance and Baroque periods.

His inspiration: “My work is inspired mostly by my experience as a Black man growing up in this country,” says Roman. Specifically, inspiration comes from what he didn’t see: images that capture the divine beauty of Black men.

“Rarely are Black men depicted as manifestations of divine beauty,” he notes. Instead, contemporary images of Black men “almost always embody political or social propaganda.”

When explaining the concept of divine beauty, Roman says it bears repeating that “our existence is not that of a human being having a spiritual experience, but a spiritual being having a human experience.” The concept of divine beauty, then, speaks to the idea of “the unseen spirit” in all of us that observes what we experience.

But in America, the evil forces of racism and white supremacy thwart the expression of divine Black beauty, giving rise to dehumanizing stereotypes “like the coon and the buck and Stepin Fetchit and Sleep ’n’ Eat — historical racial tropes that completely ignore the divinity that we all hold.”

Madrid, Missouri, Morehouse: Prior to master’s work at California State University, Northridge, Roman directed the visual arts program at Morehouse College in Atlanta.

Roman was at Morehouse in August 2014, when police shot and killed an unarmed Michael Brown in Ferguson, Mo. As protests erupted in response, “it was hitting home for all my classes,” he recalls.

In an art history course, he helped his students “walk through those waters, even though that was not necessarily in the course’s wheelhouse, just to give students a chance to feel heard.”

By chance, or perhaps something else, Roman was just about to teach his students about Francisco Goya’s The Third of May 1808, which depicts the massacre of Spanish civilians by French soldiers. In Goya’s painting, the viewers’ eye is drawn to one man, clearly unarmed, his arms outstretched in submission.

“They were like, ‘So for a least 200 years we’ve known that hands up means ‘don’t shoot.’”

“He has his hands raised and he’s in this crucifixion pose facing down these faceless soldiers with their guns pointed at him.”

His students saw the painting, learned its history, and immediately drew connections to the current moment, especially the “Hands Up, Don’t Shoot” gesture. “They were like, ‘So for a least 200 years we’ve known that hands up means ‘don’t shoot.’”

For Roman, helping to make “the typical Western art canon” relevant to a group of young Black men “who otherwise literally can’t see themselves in the world,” drove where he went with his next body of work, in which he began to use elements of the Western art canon as a bridge between the idea of divinity and its presence in Black men.

“If these young men could begin to see this art and history as relevant to their contemporary lives, then others could potentially see aspects of these Black young men in themselves through artwork.”

It is black and white: Roman’s work is almost entirely in black and white, working with charcoal and graphite.

When he worked with color, Roman found that when he presented his work, “the conversation would often shift to how I was using color and away from the concepts and content and conversations that I was trying to have through the work.”

He thinks he knows why: “The colors that we see — the color of clothing, or the color of skin tone — all point to historical and socioeconomic indicators.” (Pigments, some very expensive, were themselves economic indicators in Renaissance painting.) Colors were distracting viewers, so Roman eliminated them from his work.

Besides an intentional absence of color, the figures in Roman’s work also avoid suggestions of wealth, status, or station in life. Clothing fades to the background; contemporary jewelry becomes rosaries or beads.

Here, the goal is again to remove “historical racial tropes that completely ignore that divinity that we all hold,” he says. “I try to eliminate socioeconomic distinctions — unless they’re absolutely necessary to the conversation around the piece.”

In the end, he hopes to force the viewer to sit with, and to recognize, “their own implicit biases — as any conclusions drawn by the viewer are a result of the viewer’s own inherent beliefs.”

City and nature: Urban themes in Roman’s work “speak to the collective experience.” The natural world, he says, serves an “internal experience.” In Maine, Roman wants to explore nature, “just get out, do some hiking, find some pathways. I want to go for a walk and take my own photographs — rather than going on Google and trying to find ‘walking through the forest.’”

The art of teaching: In many instances, Roman has given students their first introduction to the arts.

“And I’ve had many students from every grade level come into my classroom thinking that art is just simply not for them or people like them. And so making work that is relevant to their experience, by pulling on my experience and at the same time simply trying to communicate the idea of being seen, of your experience being seen and your experience being valid — that’s a big deal.”

Without a trace: In his classroom, Roman will sometimes sit down next to a student and place a sheet of tracing paper over the student’s drawing.

“I’ll draw on top of it, so that they can see the difference between what I’m doing and what they’re doing, but without altering their drawing,” he explains. “A big pet peeve of mine was when a professor would just fix something on my drawing. I’m supposed to be learning how to do that. How am I learning how to do it if you just did it for me?”

Community engagement: While at Cal State Northridge, Roman joined a community-action event sponsored by Schools Not Prisons, which was working to repurpose a youth detention center in the Los Angeles area.

The organization took items from the center, like beds and nightstands, and gave them to artists, who in turn created artwork to reframe the items’ purpose and meaning. “One artist melted down a bed to mold into something else,” Roman says.

For his installation The Pipeline, Roman used several nightstands and a single bed, and covered the walls with examples of historical materials, such as newspaper headlines and wanted posters that “link the institution of slavery to our current prison industrial complex,” adding his own charcoal-on-paper portraits of Black male faces to the installation.

Creating that installation was atypical for Roman. Usually, “my community work doesn’t focus on my own artistic creation but instead work as a facilitator for a group that wants to say or speak or address something through their work.”

At Morehouse, Roman taught a mural development class. “I took a class of about a dozen students around Atlanta to look at different murals and how they were engaging the community that they were in. Then we worked with them on developing their own mural for the Morehouse campus.”