Maybe it expressed a sergeant’s snark toward the officer corps. Or a budding scientist’s thrill at a big find.

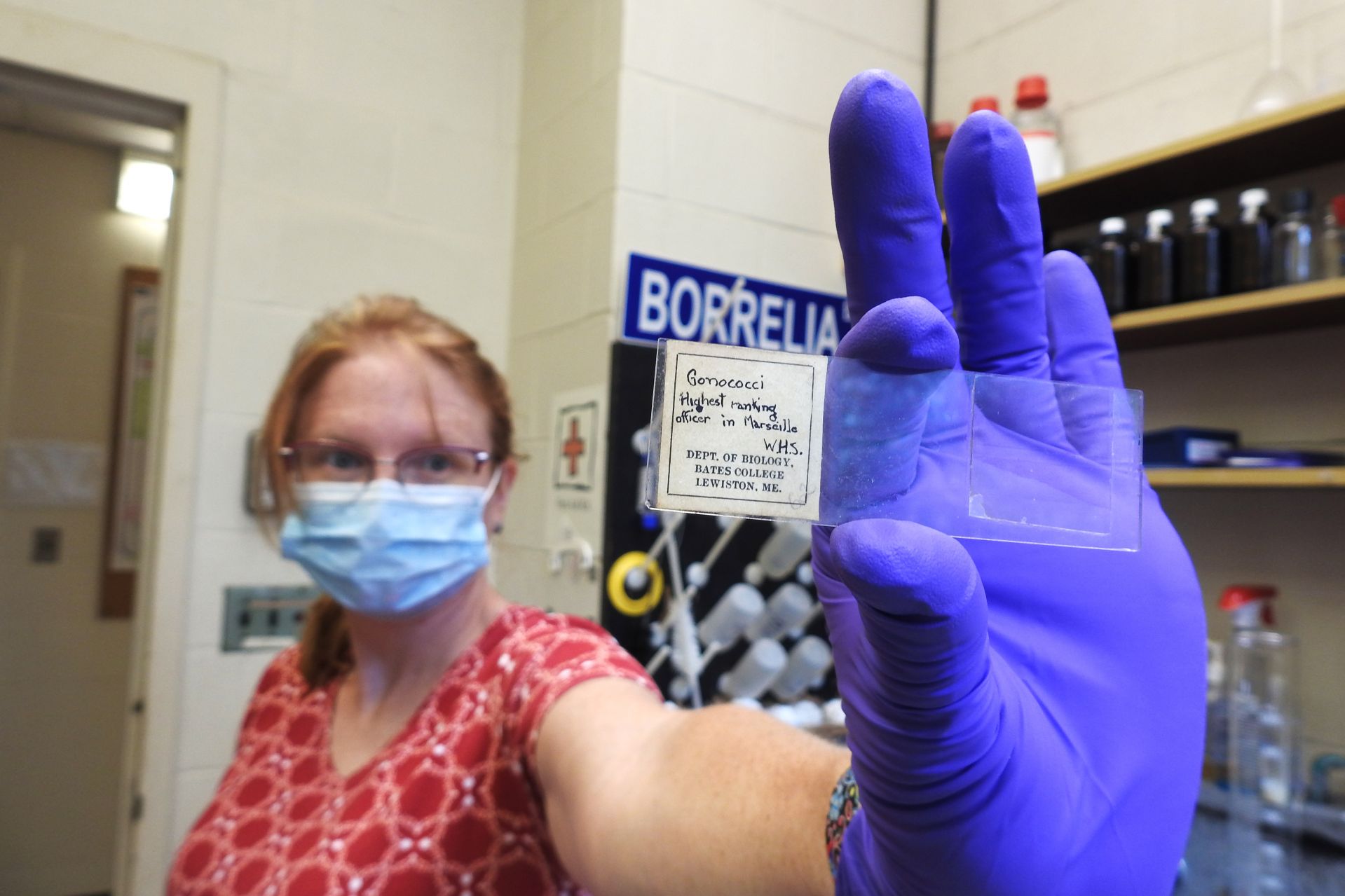

Either way, the hand-lettered label that future Bates professor William H. Sawyer Jr. affixed to one of his World War I–era microscope slides gets right to the point: “Gonococci. Highest ranking officer in Marseille. W.H.S.”

Translation: The slide contained Gonococci bacteria that, presumably, had been cultured from a specimen provided by an Army bigwig stationed in Marseille. Which meant the bigwig had tested positive for gonorrhea — “the clap.”

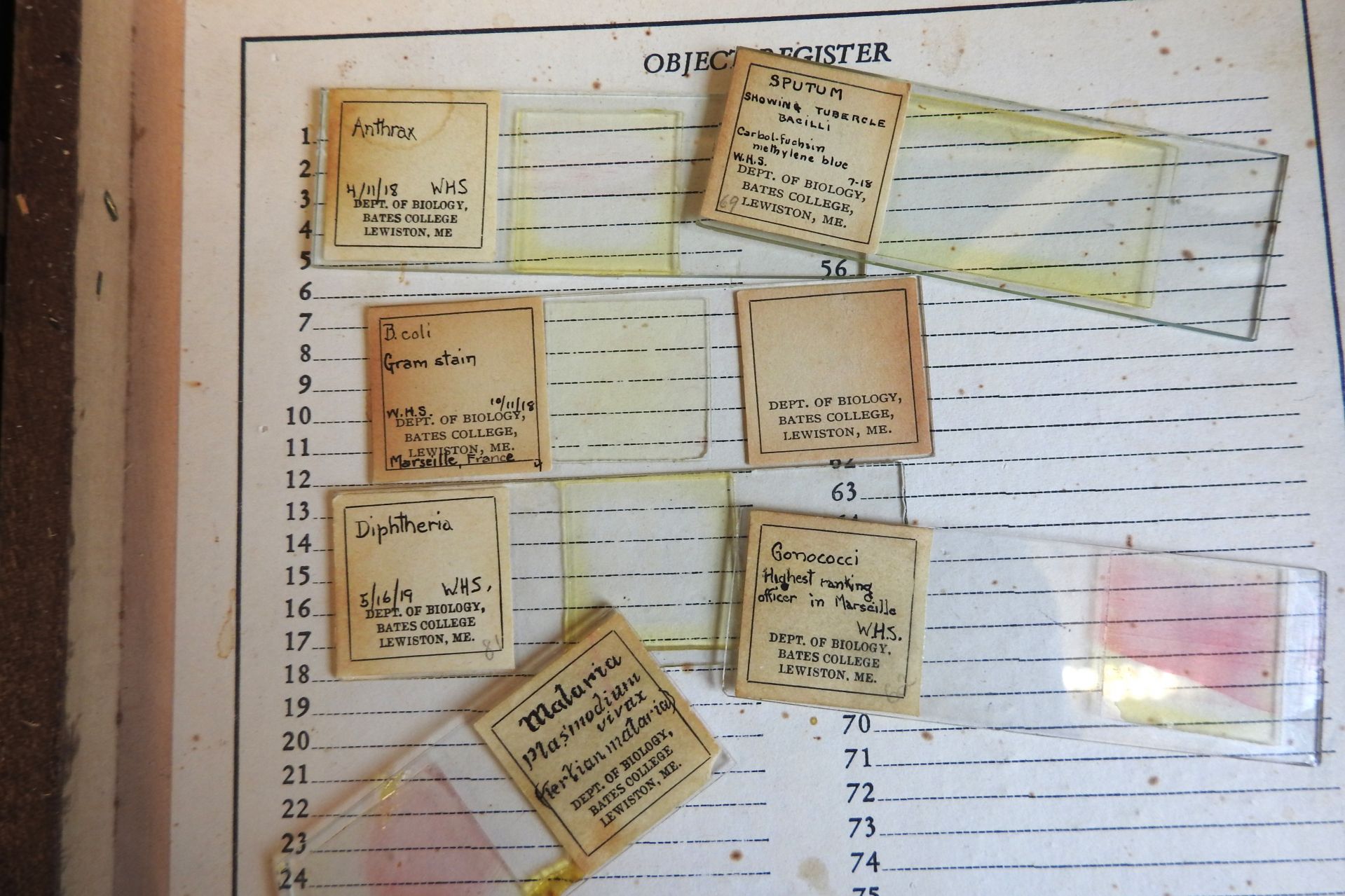

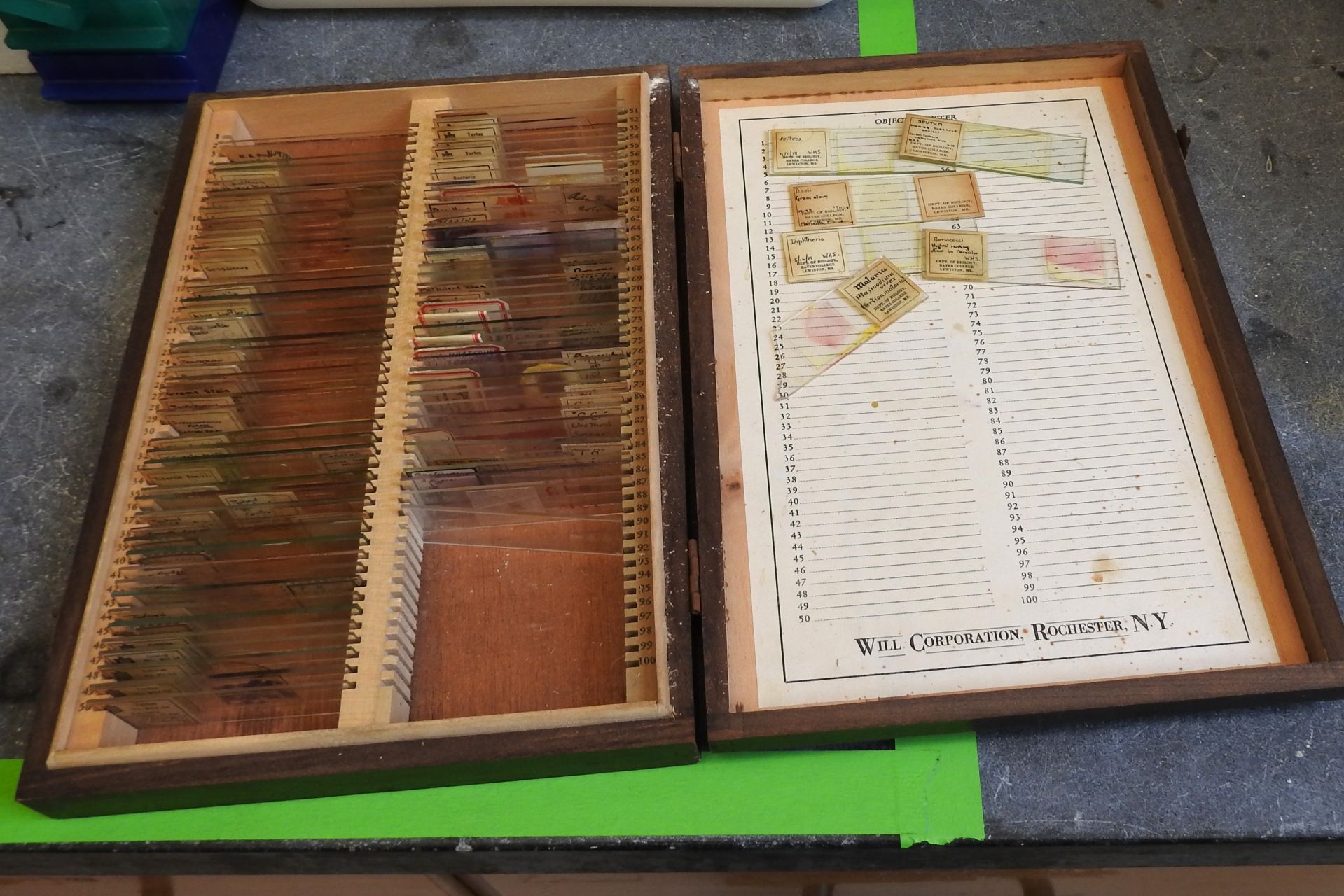

We presume this to be true thanks to the discovery last spring of a trove of teaching slides in a storage room in Carnegie Science Hall, many prepared by Sawyer, a 1913 Bates graduate, when he worked in an Army lab in the French city during the war.

Sawyer’s few dozen slides, each with his handwritten “W.H.S.,” feature a veritable What’s What of deadly pathogens that cause diseases like meningitis, diphtheria, and anthrax. (Yikes! Anthrax!? But don’t worry: All the samples are “fixed,” meaning dead, inert, and non-revivable.)

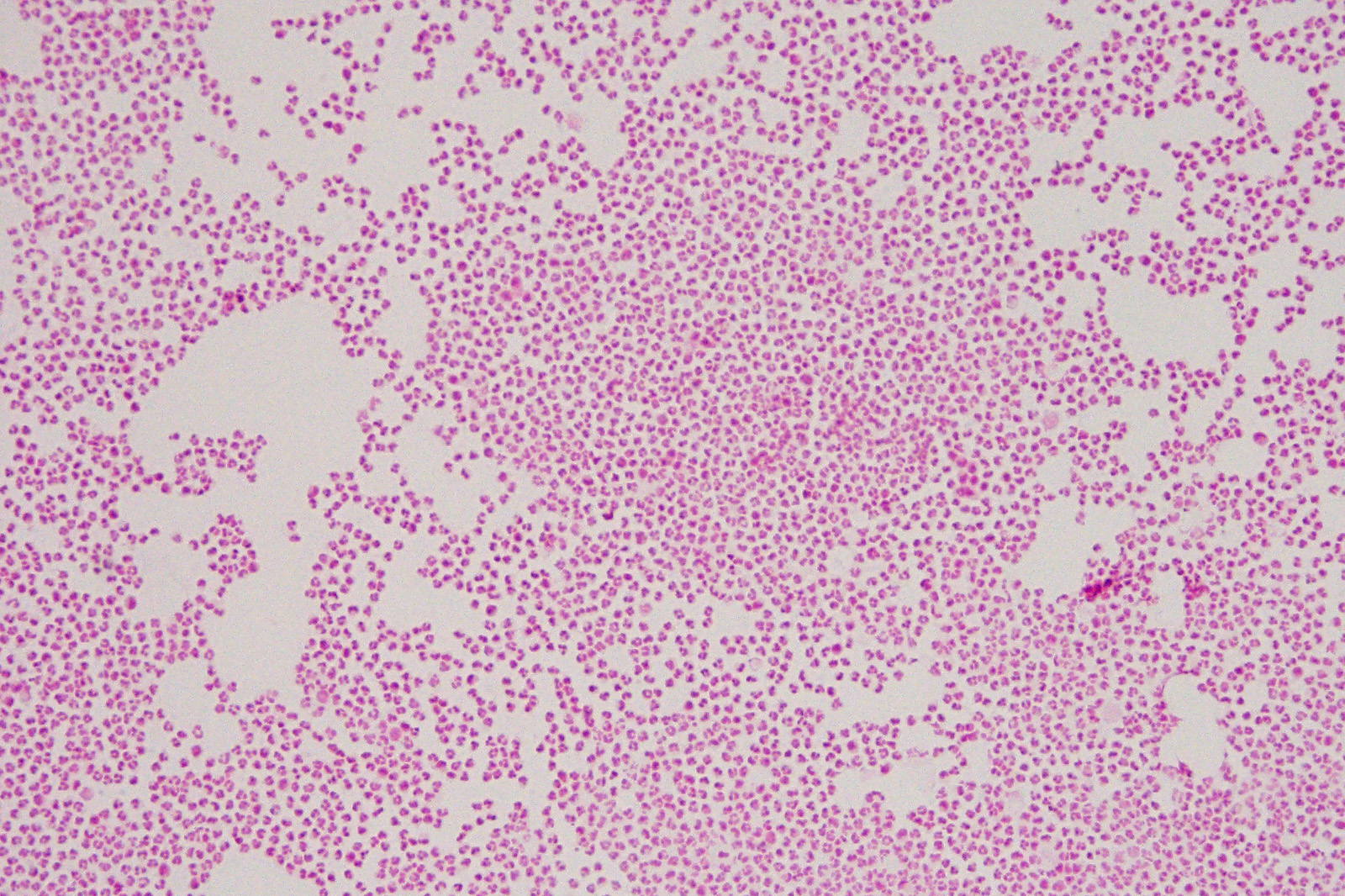

Malachowsky, who worked with a colleague to scan and digitize the old slides, says that the stained bacteria on some of the professionally prepared slides have faded over time. But the bacteria fixed on Sawyer’s slides are still visible more than a century later. “Some of that is luck,” she says. “Some are techniques. Either way, he did a good job.”

Not that Sawyer’s skill would surprise anyone. A Phi Beta Kappa graduate, he earned a master’s degree from Cornell before attending one of the Army’s new laboratory schools, at Yale, to learn the basics of bacteriology and pathology as the country ramped up to enter the Great War. After the war, he served as a Bates biology professor, retiring in 1962.

After training, Sawyer, by then a sergeant in the U.S. Army, was deployed to the port of Marseille, where one of the Army’s 11 “base sections” were funneling war supplies from incoming ships to the front lines, everything from tins of corned beef and instant coffee to trench mortars and machine guns.

These clips show what life was like in November 1918 where William Sawyer was stationed: U.S. Army Base Section No. 6. in Marseille, France, including unloading freight, such as rations and vehicles — and playing some basketball.

In Marseille, Sawyer joined the section’s laboratory, one of some 300 labs that the Army aggressively deployed throughout Europe to identify and fight the infectious diseases that always accompany armed forces.

Among soldiers, the one-two punch during World War I was influenza and bacterial pneumonia, the latter often as a secondary infection. American combat deaths in World War I totaled 53,402, but another 45,000 soldiers died of influenza and pneumonia by the end of 1918.

Meanwhile, sexually transmitted diseases cost the Army some seven million person-days and led to 10,000 men being discharged. Indeed, among Sawyer’s slides, Gonococci specimens are by far the most common, says Anna Marie Bowsher, a research technician who worked with Malachowsky to image the slides, preserving the evidence of Sawyer’s wartime work for future generations.

“The slides themselves are interesting but you don’t really know anything until you put a slide under the microscope,” says Bowsher. “Even today, there’s a lot of things that we don’t know until we look under a microscope. I think that’s really cool.”

Bowsher is also captivated by the fact that Sawyer cared enough about his work to bring the slides back to Bates. “I can’t imagine ever having the opportunity to do what he did — work in a military base lab — so it was great to live vicariously through the experience” of imaging the slides.

All those Gonococci slides suggest that the disease was widely present at Base Section No. 6, says Bowsher, who works in the Bates lab of Travis Gould and Paula Schlax. Only the “highest ranking officer” slide has such a detail on its label.

Maybe, says Bowsher with a chuckle, Sawyer notated the officer on his label to record a brush with fame, “like seeing a celebrity at the mall. Maybe he was like, ‘I got to interact with someone I never would have met otherwise by taking his sample and looking at it.’”

(And who exactly was the “highest-ranking officer” with the clap? An educated guess says it may have been Col. Melvin W. Rowell, who, as Army records indicate, stepped down from his base section command in March 1919, when the station was still active.)

Captivated by the science and history of Sawyer’s slides, Kennedy has been pondering “what it means to find these slides, many prepared during the 1918 pandemic, during today’s pandemic.”

From a biomedical perspective, “we’re in a very different place now.” In 1918, scientists didn’t yet know about viruses. “Now, we saw accurate illustrations of the new coronavirus even before it was detected in the U.S.”

But politically, “we’re in a similar place” when it comes to the pandemic, Kennedy says. “In 1918, the mask became a political symbol, and there were riots about it — which always seems to happen with disease: People tend to get frustrated and turn on one another politically.”

These days, Kennedy is teaching students the newest concepts in neuroscience, such as the physical underpinnings of our memories and emotions. He has pondered what slides Sawyer probably created in Marseille but did not keep for his Bates teaching.

In 1918, school was still out on what organism was causing the pandemic. “There was considerable debate in the scientific community, mostly centered at Rockefeller Institute, about the cause of influenza,” says Kennedy.

At the time, many scientists thought that Pfeiffer’s bacillus caused influenza because the bacteria was found in the lungs of people sick with the flu. (Scientists were so confident of the bacterial cause that Pfeiffer’s was renamed Haemophilus influenzae.) But as it turned out that the bacterium was only a secondary invader after the influenza virus.

For a scientist during wartime, the ability to culture and mount bacteria on a slide for examination under a microscope “was seen as a critical part of the health system,” says Kennedy. With Sawyer in Marseille at the height of the pandemic, there’s little question that he was trying to culture H. influenzae. Given the overall high quality of Sawyer’s other slides, says Kennedy, “I’m confident he was probably able to culture H. influenzae,” which is notoriously difficult.

And some of the pathogens that Sawyer cultured and mounted in 1918–19 in Marseille were doozies: Bacillus anthracis (which causes anthrax), Balantidium coli (balantidiasis), Corynebacterium diphtheriae (diphtheria), Mycobacterium tuberculosis (tuberculosis), and Neisseria meningitidis (meningitis).

But no H. influenzae is to be found. Kennedy’s theory is that “he probably brought them back but then didn’t keep them when it was found out that H. influenzae was not the cause of influenza.”

What scientists and other scholars do, explains Kennedy, is filter out what’s no longer thought to accurately explain our world. “I don’t tell my students, ‘We’re going to learn something today that’s no longer true.’ We don’t teach phrenology,” the idea that skull shape reflects personality. And in Sawyer’s case, he may have quite literally “filtered out the slides that weren’t important for his students.”

As a comparison, Kennedy describes how his neuroscience students are learning concepts that replace filtered-out ideas from just a few years ago. “Fifteen years ago, it was thought that only about 2 percent of the genome was useful and the rest was ‘junk DNA.’ But we know now that, in fact, pretty much all DNA is recruited for some process besides encoding for proteins.”

“So my students don’t know the ‘junk DNA’ idea — which seems amazing to me, because everyone over the age of 25 knows it well.”

Sawyer, who died in 1963, two decades before Kennedy was born, would be happy to know that his slides have found their way back into a Bates classroom.

At Bates, even basic courses are taught by professors, not teaching assistants. This fall, Kennedy taught a First-Year Seminar, “The Molecular Brain.”

In part, the course examines how researchers continually adjust their thinking about what’s true, such as how the brain works.

He showed the students Sawyer’s collection. “They thought the slides were wild.” (Indeed, it’s unlikely that any other college has such a collection.)

As Kennedy thought about finding slides during one pandemic that were created during a different one, he wondered what life might’ve been like at Bates during the 1918 pandemic — and what future generations will wonder about life at Bates in 2020–21.

As a class project, his students journaled about what it’s been like starting adulthood at Bates during a pandemic. “We’re going to seal these journals — I’m writing one, too — into a time capsule, and they have to design a mechanism by which this capsule is hand-delivered to a member of the Bates community of their choosing 100 years from now.”