![Mural on the wall of row houses in Philadelphia. The artist is Parris Stancell, sponsored by the Freedom School Mural Arts Program.Left to right; Malcolm Shabazz (Malcolm X), Ella Baker, Martin Luther King, Frederick Douglass.The quote above the pictures,"We Who Believe in Freedom Cannot Rest", is from Ella Baker, a founder of SNCC (Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee), a civil rights group. which amongst other contributions, helped to coordinate "Freedom Rides"in the early 1960's.Tony Fischer [CC BY 2.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0)], via Wikimedia Commons](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2019/01/feature-crop-Mural_Malcolm_X_-_Ella_Baker_-_Martin_Luther_King_-_Frederick_Douglass-1-200x133.jpg)

Kathryn Tibbetts Gates ‘91 was having supper in old Commons when a friend burst into the dining hall and shouted, “We’re at war!”

At that moment, Gates had two thoughts: Her friend had entered through the exit door, so her automatic response was, “You can’t come in this way — you’ll get in trouble.” Her second: “I will always remember this moment.”

Such was the seismic surreality of Jan. 16, 1991, when the U.S. went to war.

It was around 7 o’clock in the evening and the TV networks had just broken the news that U.S.-led military forces were bombing Baghdad, Iraq, beginning the first Gulf War.

At that time, another senior, Pam Batchelder Johnson ’91, was downtown at the Cage with friends, trying to enjoy “Burgers and Brews” night. “Not a classy start to my story, but true,” she says.

The Cage’s TV was tuned to the evening news. Shortly after 7, NBC News’ Tom Aspell, based in Baghdad, told Tom Brokaw, “It’s very quiet.” About a minute later, Brokaw turned back to Aspell, now highly agitated, who said, “The sky’s just full of tracers. There’s a big explosion. Now guns and more explosions. Red tracers, white tracers, going up all over the place.”

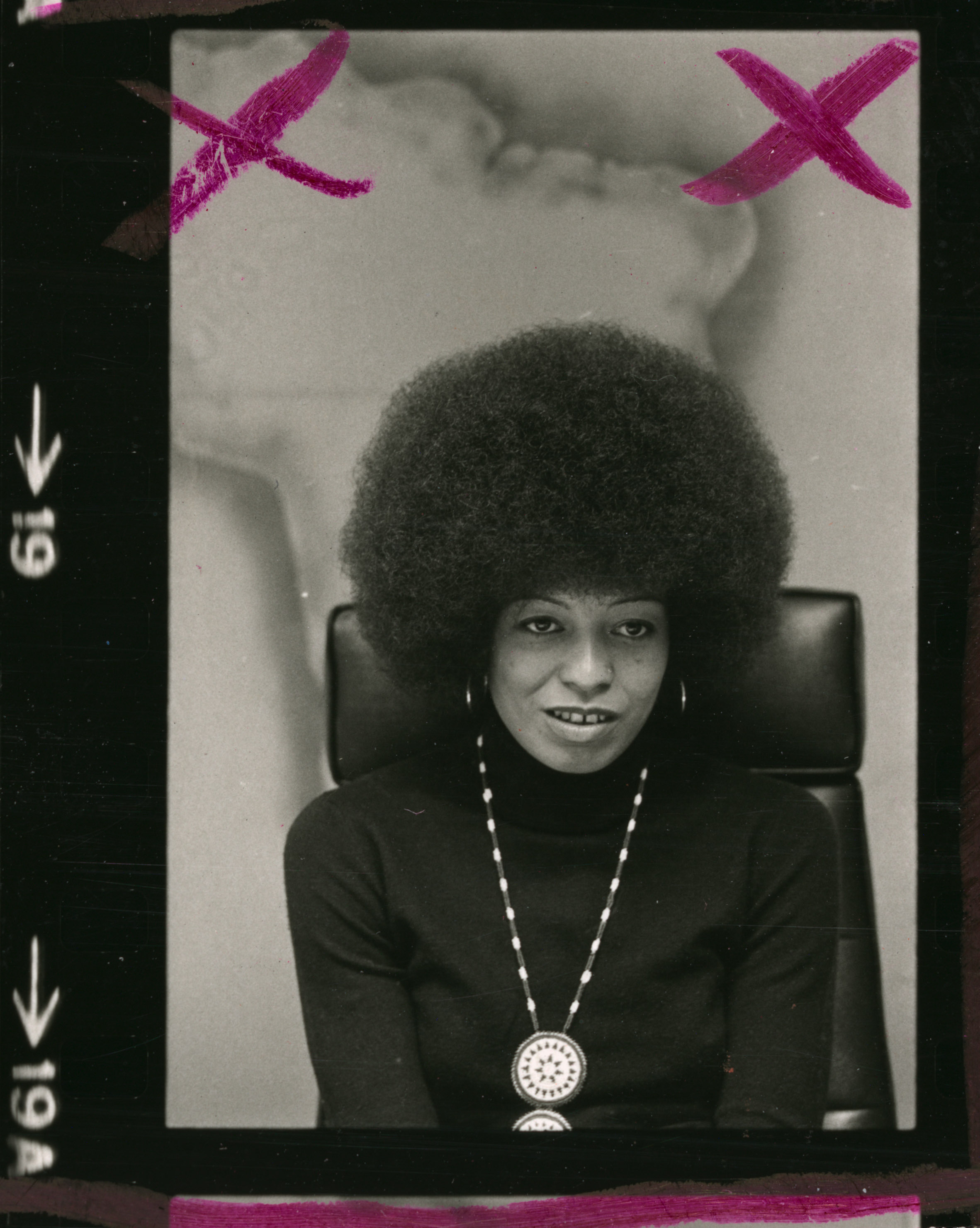

“I started crying,” Johnson recalls. She was with Elise Berkman ’91, who suggested that instead of more beer, they should decamp to campus to hear a scheduled talk by activist and scholar Angela Davis. “So we did.”

Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division)

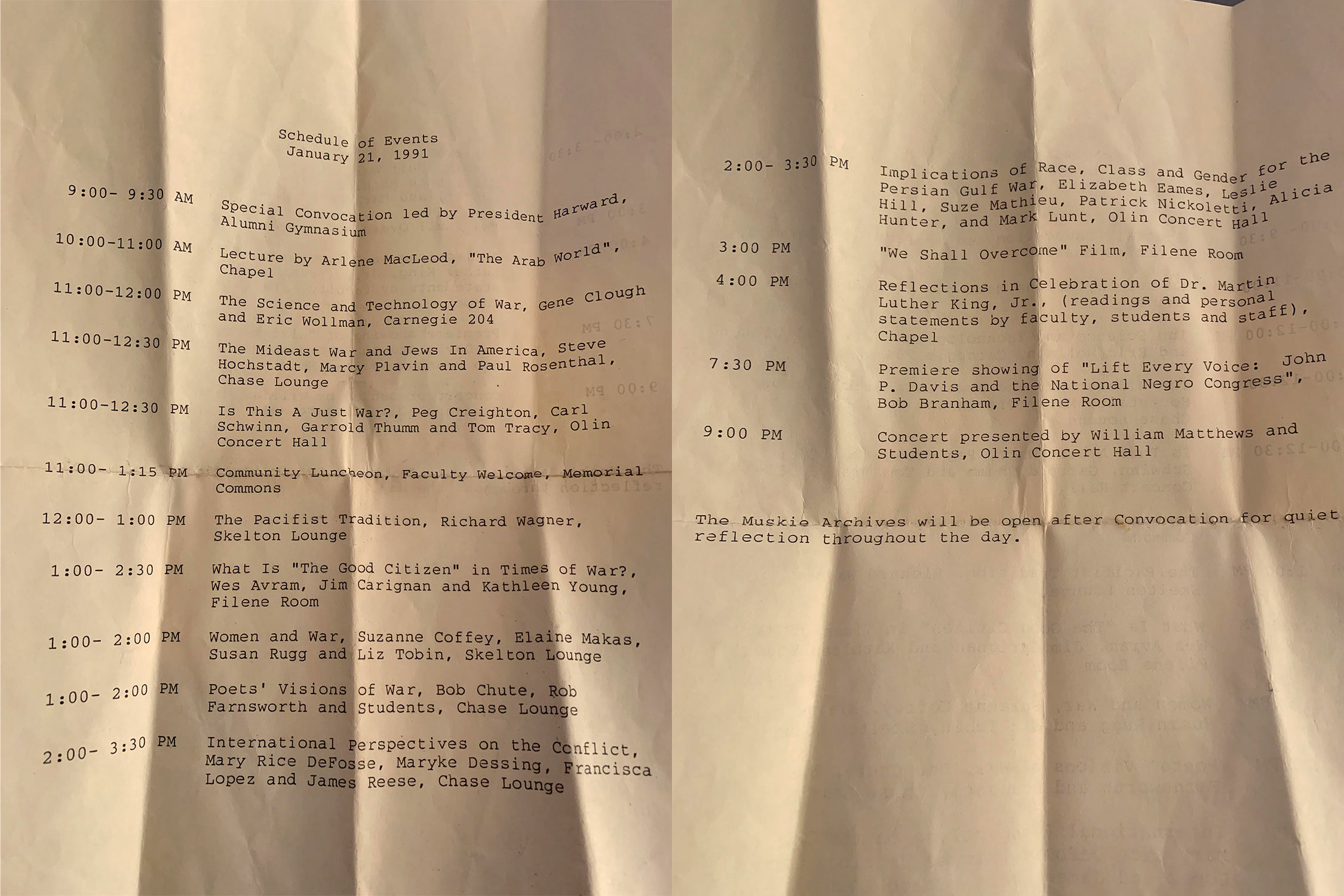

The chapel was packed (as it was the week before when Sen. Joe Biden spoke). Someone had hung an anti-war banner across the pulpit. Before the talk, then-Dean of the College Jim Carignan ’61 made an announcement: Any student group planning an event responding to the war should come over to Chase Hall by 8 o’clock the next morning with their event information so it could be “typed up” and included in a published schedule of events.

Liz Tobin, then a professor of history and now retired from a deanship at Illinois College, introduced Davis, praising her contributions to “theoretical work on American politics, Black liberation, and the fight for women’s equality.”

Angela Davis at MLK Day 2021

On Monday, 30 years after her 1991 talk at Bates, the iconic activist, intellectual, and scholar “returns” to Bates as the keynote speaker for our virtual celebration of Martin Luther King Jr. Day.

Tobin pointedly said that “only those of you who were politically conscious in the early 1970s can imagine how I feel about this moment.”

Davis then walked to the lectern and began her talk. “I did prepare a lecture for this evening, which” — and here she paused for nearly two dramatic seconds — “I will not deliver.”

Davis’ long pause has stuck with Sonja Hyde-Moyer ’91, a Canadian at the time who is now a U.S. citizen. She realized that a major American moment was unfolding. “I remember feeling like I was part of an American conversation that night.”

A few in the audience clapped with appreciation as Davis jettisoned her original talk in favor of helping the Bates audience make sense of what was unfolding in the Middle East. “I remember the anger and fear about the situation unfolding,” says Johnson. “It seemed so fortuitous to have a leader like Angela Davis on campus that evening.”

In the final 16 minutes of her 1991 talk at Bates, Angela Davis offers lessons about collective action, inclusion, and the difference between racial autonomy and racial separatism.

The original title of Davis’ talk was “Race, Gender, and Class.” Instead, she used those lenses to dissect the new war. She shared how, minutes before, she’d been in her Bates guest room watching TV, and saw the first official notification of the attack from White House press secretary Marlin Fitzwater. Reading a statement from President Bush, Fitzwater said, “The liberation of Kuwait has begun.”

As she settled at the lectern, Davis admitted feeling “rather bizarre.” The day before, she’d been more than 3,000 miles away, acting in solidarity with some 6,000 other protesters in San Francisco.

The throng had shut down the Federal Building and blocked the Bay Bridge. The next day, the San Francisco Examiner’s headline screamed “On the Brink,” a reference to the United Nation’s deadline for Iraq to pull its troops out of Kuwait, or else face military action.

Now Davis was in Lewiston, Maine, light years from the West Coast epicenter of American protest. “This is a very frightening period,” she said. “With perhaps one exception, I don’t ever remember feeling the way I feel now. That one exception would be the invasion of Cambodia during the Vietnam War.”

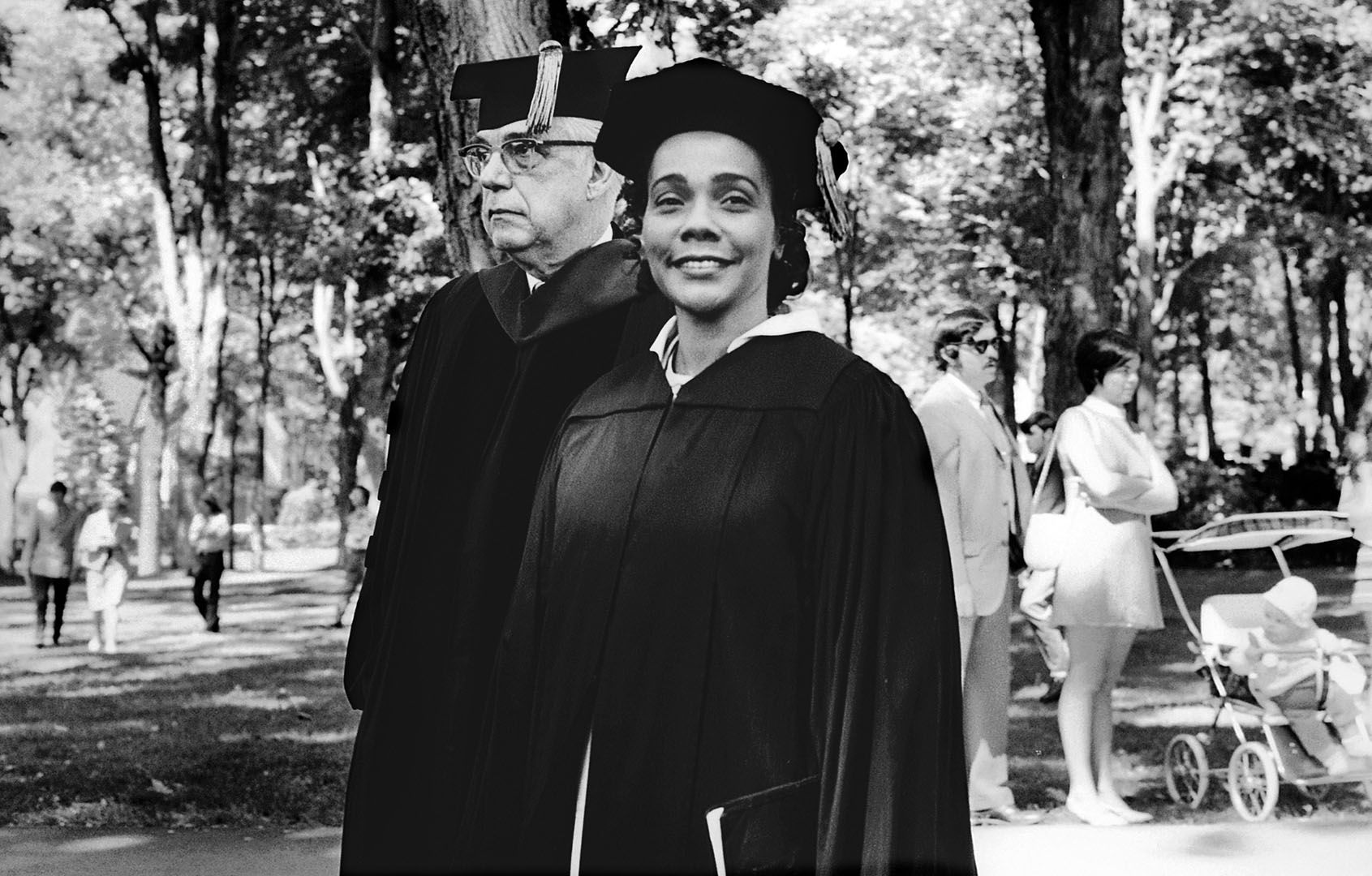

The Vietnam-war era saw Davis begin to acquire notoriety — as well as the dawning recognition by many that she had been unjustly treated. When Coretta Scott King gave the 1971 Bates Commencement address, she spoke about Davis, who was then in jail, enduring a 16-month incarceration (that would end in her acquittal on felony charges in 1972).

“Racism is repression, and the repressive clouds that now hang over our country have become heavier in the weeks that Miss Angela Davis has languished in jail,” King said. “While I sharply disagree with the politics of Miss Davis, I must say that if her Blackness, her politics, and her womanhood are being judged, and not the crime, then all Americans will lose some of their liberties along with her.”

Now in 1991, Davis was forthright in telling her audience she felt disconnected by being in Maine. “Because as I was saying before, I felt really out of place. What am I doing, sitting in a guest house” at Bates College? The cure to feeling alone and “really out of place,” she said, was to “to feel a community with you.”

And that’s what Davis would create at Bates over the next few hours: connection with the Bates community.

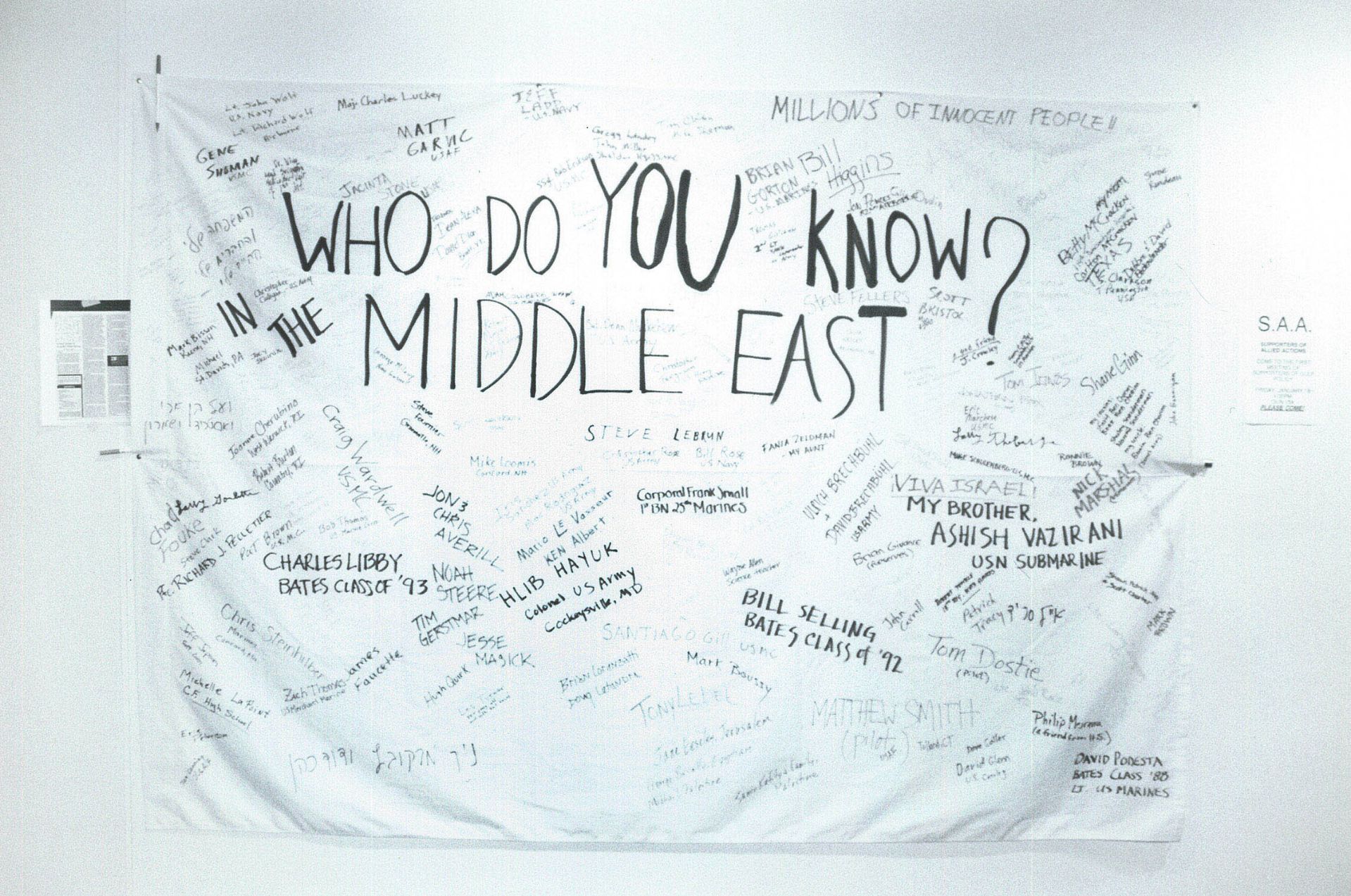

“I remember her talking about how people she knew who had enlisted in the military — some of whom were her own students — had done so because there simply was no other way for them to get out of poverty, to get an education,” recalls Hyde-Moyer. “And now, they were going to have to risk their lives halfway around the world for a war that had no relevance to them, that wasn’t about freedom, however the politicians were trying to spin it.”

It would not be enough, Davis told her audience, including many students already skilled at activism, and champing at the bit to take to the streets in protest — to simply oppose “war.” True, she said, “there will be those who will demonstrate against the war because they are morally opposed to war.”

As you think about the need to go out there and express your opposition to the war, remember that there is a lot of business that you have to take care of in your own backyard, in your own living room.

But, she said, “I think we should go much further. We need to understand the significance of this war, its implications, not only with respect to the people of the Middle East, but its implications with respect to people here at home. And we should recognize that.”

That meant focusing on race, gender, and class in our understanding of American events. From her talk, here are three samples of how Davis spoke to those issues:

- Having examined the history of this country in which I live — this country which my ancestors, kidnapped from the shores of Africa, have been responsible for creating with their labor and their sweat and their blood— I can say that this war underway in the Persian Gulf is situated on a continuum of historical imperialism, exercised by generations of U.S. governments….

- And it seems that F-15 fighter bombers…have taken off from the bases in Saudi Arabia, each carrying 12 500-pound bombs. It also seems that cruise missiles, Tomahawk missiles — and isn’t it amazing the way in which the legacy of the indigenous people of this country has been violated by the U.S. military when you consider the name of Apache helicopters, Tomahawk missiles?”

- [This] is a racist war because it is an imperialist effort conducted against a people of color. The liberation of Kuwait? Since when has the U.S. been interested in the liberation of any people of color anywhere in the world?… I don’t remember having heard any talk of a deadline with respect to apartheid in South Africa….

Davis also spoke about the need to address racism on the Bates campus, asking that “as you think about the need to go out there and express your opposition to the war, remember that there is a lot of business that you have to take care of in your own backyard, in your own living room.

“If you don’t begin to try to work out some of these problems that stem from racism on this campus, then how are you going to build a movement against that war?”

She challenged the college to create spaces for Black students. “I know there is this notion that we are all equal, and yes, we should be. But historically some of us have been marginalized and oppressed to a greater extent than others of us. And sometimes we need a space.

“She did then as she does now, call for self-reflection, respectful political allyship, and collective action.”

The desire “is not a separatism,” she said, but a drive toward “autonomy. As an African-American woman, there are times when I only want to meet with my African-American sisters, because there are issues that I can discuss only in that space. But that isn’t to say that I am opposed to working with African-American men. That isn’t to say that I’m opposed to working with European-American women or men.”

As a college student, Davis studied at the University of Frankfurt in West Germany, with the philosopher Herbert Marcuse. She has said that he taught her “that it was possible to be an academic, an activist, a scholar, and a revolutionary.”

And that’s what Professor of Politics Emerita Leslie Hill, saw that night: a powerful and effective “historian, political analyst, and an organizer. She did then as she does now, call for self-reflection, respectful political allyship, and collective action.”

As a Black professor in only her third year on the Bates faculty at that point, Hill felt “pride and affirmation,” that night in the chapel, “something that did not come often in my life on campus.”

Hill felt “pride in the power of a Black woman speaking truth to power: national, institutional, socially privileged power. Affirmation for an analytical approach that recognizes the significance and consequences of gender and racial politics. And inspiration to keep doing that work in ways that call forth collaboration and community-building.”

Hill also felt enormous respect for Davis, and not just for her famous track record of activism.

“In 1972, when I first heard her speak, she did not — in fact, refused to — identify herself as a feminist,” says Hill. “In this 1991 speech, she clearly saw herself as a Black feminist. How often do we see public intellectuals ‘course correct,’ reveal their own altered thinking and changes of mind? We can all learn and grow. That was the message: so rich.”

Prior to the talk backstage, Liz Tobin recalls a brief and polite conversation with the famous radical. “While I was nervously awestruck, she was preparing like all other professional speakers: The revolutionary becomes academic.”

But as Davis offered a fiery, radical opposition to war and racism and explained the connections between the two, Tobin saw that Davis had “remained supremely charismatic.”

After speaking extensively about issues of race, gender, and class with respect to the new foreign war, Davis ended with a pep talk, as it were.

“As you attempt on this campus to create the strongest possible opposition [to the war], do not think that you are isolated,” she said. “At this moment, there are people in gatherings like this and out in the street and in churches not only in this country, but all over the world.

“So reflect upon your membership in that larger community, as you work here in Maine. Some of you are probably going to want to take off and go somewhere else where the action is, but you have to create action here.”

Her final words: “Fight the power!”

And if Davis yet again confirmed her bona fides as a public intellectual during her chapel talk, what came next, her talent for inspiring collective action, was equally dazzling.

“Celeste asked, ‘Why do you think the march will go downtown?’ I said, ‘Because Angela Davis just announced it from the podium.’”

The video of the talk concludes as two students speak from the lectern, announcing a protest march starting at Chase Hall. The audience streams out, and the video stops.

But folks there that night remember Davis, at some point after the conclusion of her talk, making a call for action herself, saying that the student protesters should march downtown, and not just around campus. “I distinctly recall AD saying, ‘We’re going to march — downtown!” recalls longtime student dean James Reese.

“I also distinctly recall going to the custodian’s closet in the chapel hallway, where there was a phone, and calling Celeste [Branham, then dean of students] and mentioning that students would be marching downtown. Celeste asked, ‘Why do you think the march will go downtown?’ I said, ‘Because Angela Davis just announced it from the podium.’” (During the march, Lewiston police provided safe passage downtown.)

Reflecting on Davis’ call for a downtown march, Reese wonders if she did it to “perhaps emphasize to the students that ‘you must go bigger.’ It seemed she thought it would work. When it did work, it suggested to me that her confidence was from years of experiences that taught or informed her that taking control as much as you can is the best way your goals can be achieved.”

The Bates Student described the march, with Davis joining, as starting at Chase and heading toward Merrill Gymnasium, then past Olin Art Center, and to President Harward’s house. There, Don and Ann Harward met briefly with students, inviting those who wished to come inside to discuss the event and share thoughts.

From there, the crowd marched to Kennedy Park. Johnson recalls the “snow and cold; we were marching through the snow. I carried a citronella patio candle that Mrs. Harward had given to me; she was marching next to me.”

At Kennedy Park, the group heard speeches from the park gazebo, the one John Kennedy spoke from on Nov. 6, 1960. Elise Berkman recalls Professor of Rhetoric Robert Branham speaking, as well as Celeste. “I vividly remember Professor Branham stating that President Bush was ‘pleased as punch’ in declaring war.”

Peter Carey ‘91 remembers many, including Davis, returning to Frye Street Union for a reception that was also a TV news watching party. “She was in the front ‘row,’ on a couch, just in front of me,” he recalls.

“We stood shoulder to shoulder,” recalls Kirk Read, professor of French and francophone studies. It was his first year on the faculty as an instructor, and he had anticipated Davis’ visit “like a rock star was coming to campus.” Now he didn’t know where to look, at “George Bush announcing the ‘liberation’ of Kuwait or at Angela Davis, whose commentary we were hanging on. Her grace, experience, steadfastness, and commitment were an anchor in an enraging and confusing time.”

The next day, Reese drove Davis back to the Portland Jetport, along with two exchange students from Russia, who were flying from Portland to a conference. “They sat in the back seat and smiled the whole time, knowing they were riding with America’s most well-known Communist,” Reese recalls.

The roads were salty wet after the overnight snow, and he’d run out of windshield washer fluid in his vehicle. The windshield was becoming covered in salt, so he kept close to the vehicle in front to take advantage of the tire spray onto his windshield.

“I think ‘AD’ noticed, but we talked about support on campus and support for Russians. I thought it was some damn good driving and conversation.”

What happened next is well-recorded Bates history. On Friday, Jan. 18, the faculty voted to cancel classes on Martin Luther King Jr. Day and hold a day-long teach-in. And by the mid-1990s, MLK Day at Bates had become what we know today, a full teach-in day in lieu of traditional classes, with talks, workshops, readings, and screenings.