An icon of the international racial justice movement offered a timely reminder of activism’s value during Bates’ Martin Luther King Jr. Day programming.

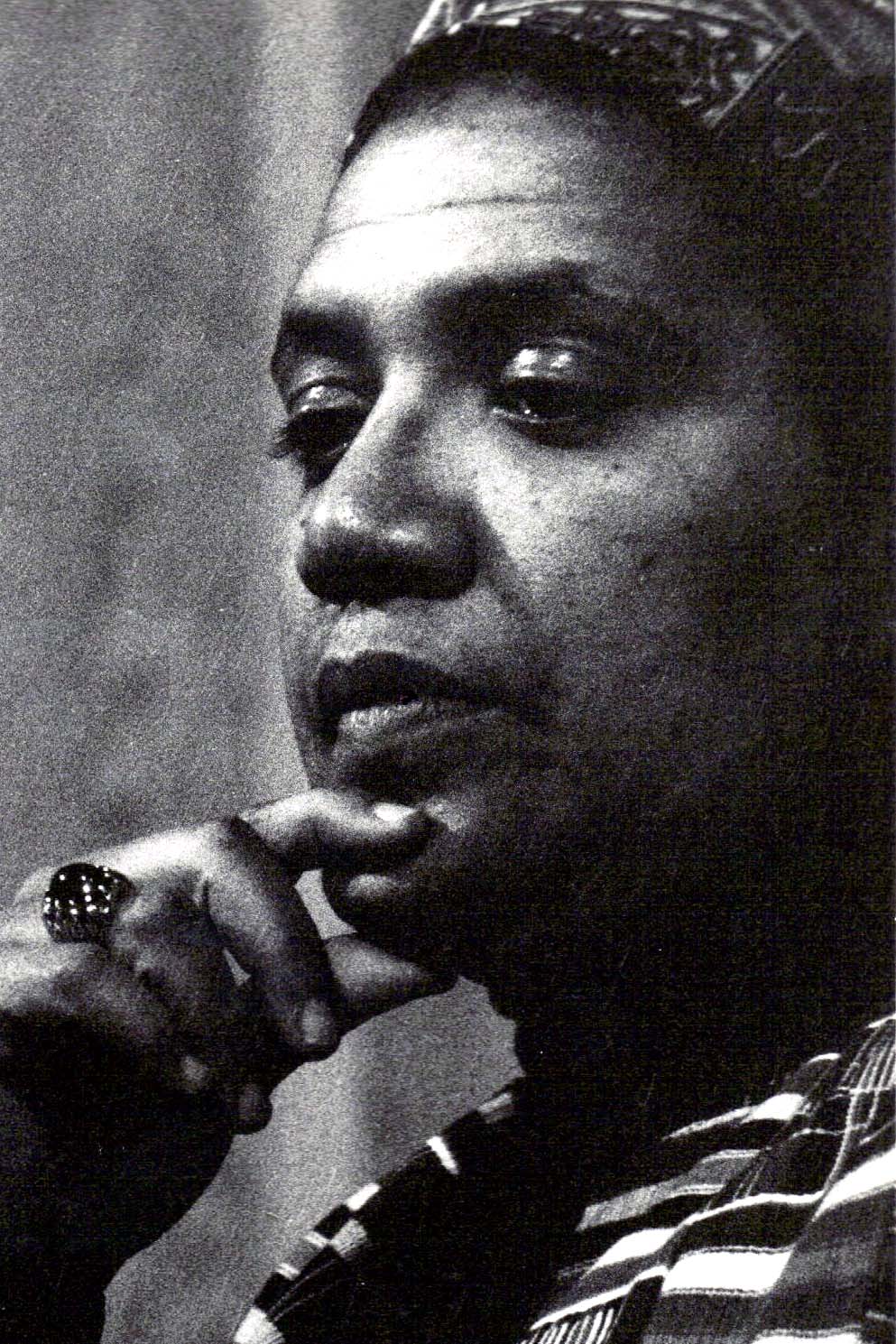

“I’ve pointed out many times that the electoral arena is not, by itself, going to bring about change,” author and scholar Angela Davis said during the Jan. 18 keynote discussion. Responsible public participation in civic life beyond voting is still essential.

When Barack Obama was elected president, Davis said, “it was a world-historical change. But then people didn’t continue to make demands. There were those who assumed that because a black man was elected, all we had to do was sit back and let him move the world forward.

“And of course we should have been out in the streets demonstrating from the moment of his inauguration. And then things might’ve turned out differently.”

That remains an exigent lesson. With the election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, Davis continued, “we’ve finally witnessed one important victory against looming fascism. But that does not mean that we step back. It does not mean that we don’t continue to demonstrate and make demands that Biden and Harris will be compelled to seriously examine.”

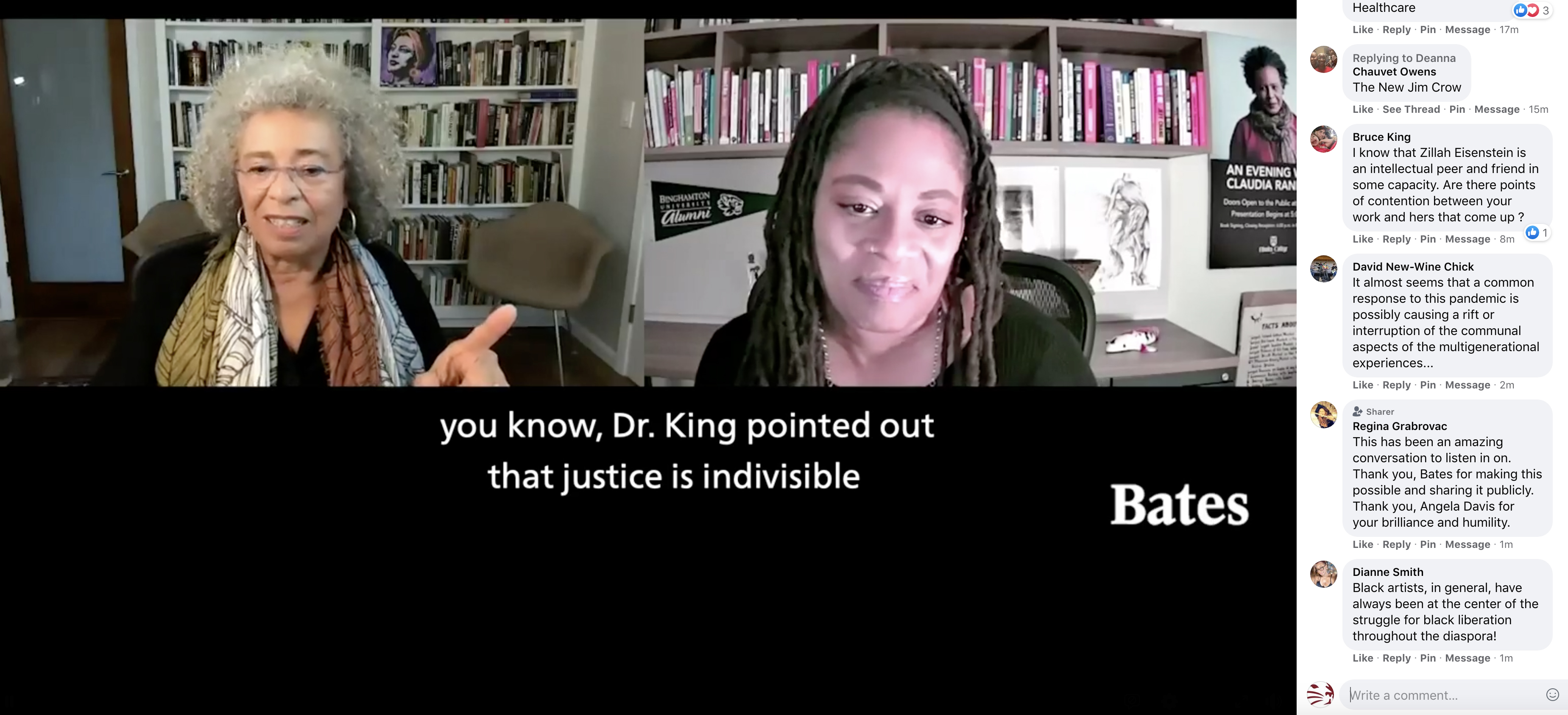

With Bates’ 2021 programming presented remotely because of the coronavirus, the keynote event took the form of a prerecorded long-distance Zoom conversation between Davis and Therí Pickens, professor of English and chair of the college’s Program in Africana. This year’s keynote session also included a new feature, a Q&A with a group of Bates students.

For Davis, an outspoken opponent of what she terms the “prison-industrial complex,” the “visit” to Bates was her second. The first was in 1991, when she spoke to a chapel audience on the night of the start of the first Gulf War. (Two days later, the Bates faculty voted to honor King’s legacy with a teach-in on his birthday.)

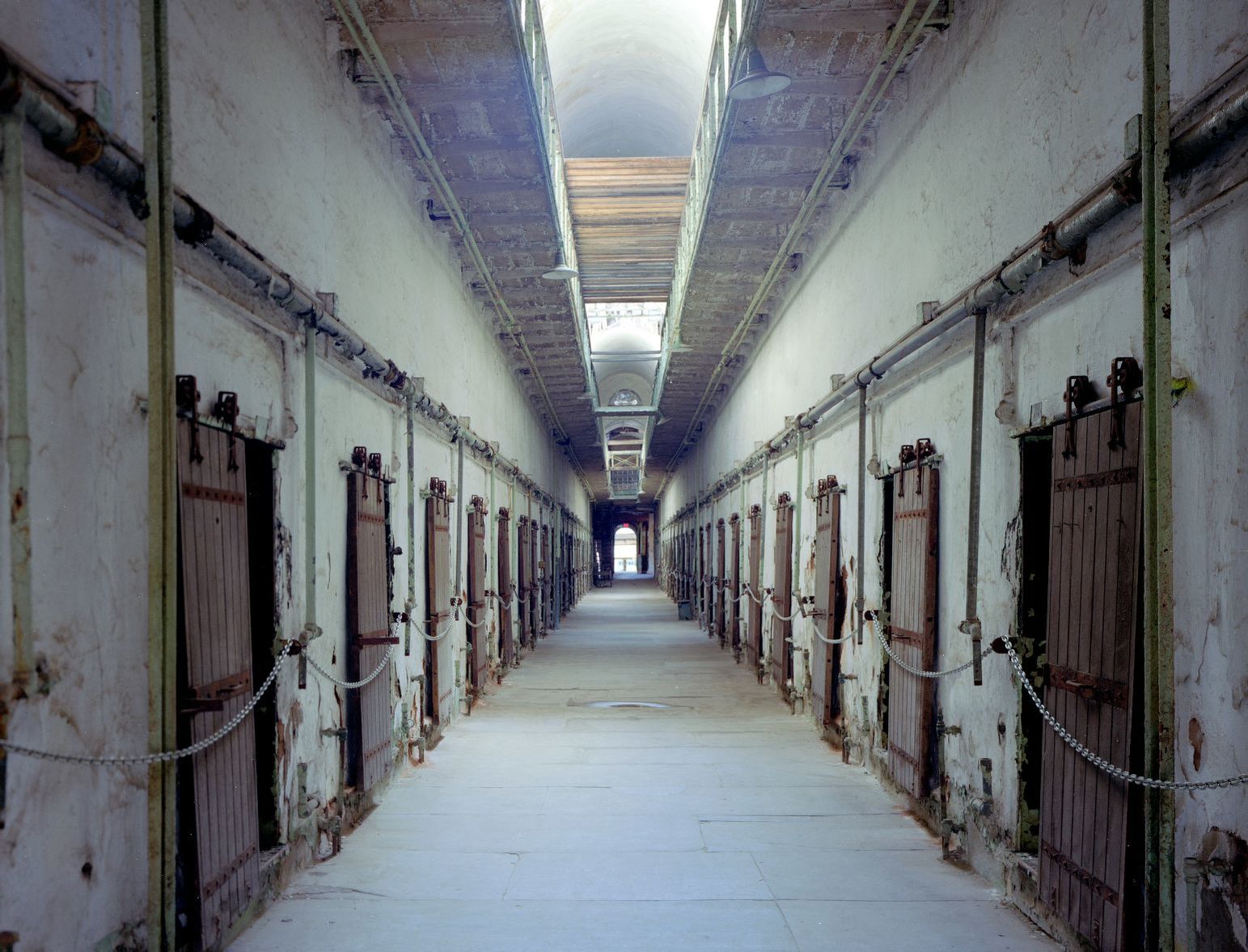

A theme throughout Davis’ work has been the social problems associated with incarceration and the criminalization of communities hard-hit by poverty and racial discrimination. Her influential critique of the carceral system dates back to her own conviction and jailing on felony charges — she was ultimately acquitted — in the early 1970s. She was a founder of Critical Resistance, a national organization dedicated to the abolition of the prison system.

In addition to 2003’s acclaimed Are Prisons Obsolete?, Davis’ nine books include 2016’s Freedom is a Constant Struggle: Ferguson, Palestine, and the Foundations of a Movement. She is Distinguished Professor Emerita of the History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

“Confronting Our History; Justice for Coming Times” was 2021’s theme for MLK Day at Bates. President Clayton Spencer opened the session with remarks that emphasized Davis’ belief in the “inherent connection between education and action.”

For Davis, Spencer said, “Significant social transformation is always grounded in education, and the overarching purpose of knowledge is, indeed, to make a crucial difference in our social world.” Bates’ MLK programming “urges us to reflect consciously and intentionally on what we owe our students and what we owe the world.

“It demands that we connect the personal liberation required for our students’ growth and realization as individuals with the collective imperative that we use knowledge for the public good.”

In the context of the King holiday, “Confronting Our History” could refer to just about anything, but in fact “Our” hit very close to home: a substantial portion of the programming scrutinized areas in which Bates has fallen short of its commitment to racial justice. Yet, as Angela Davis said in her conversation with Pickens, the very tensions created by such contradictions between aspiration and outcome can be productive.

We’re typically taught that contradictions “are to be resolved,” Davis said. “One is urged to figure out which is the right way, and so one chooses one side or the other. But what if we hold both in tension and see, as [poet and activist] Audre Lorde said, what gets creatively generated by the tension of this contradiction?

“In that context, I would say that universities are so important” — and for people of color at predominantly white universities, “it’s important to embrace that.” Such folks must, of course, “recognize that the institutions that we inhabit are products of slavery and helped to reproduce racism.” But at the same time, academe “is the venue where we are able to develop the capacity to make critical interventions, to work against racism.”

She continued, “It’s often difficult to encourage people to hold those polar opposites in tension and to embrace the contradiction there, rather than assume that, ‘What I have to do is to leave this venue and find some other place that is going to be more relevant or better-suited.’

”My position is that wherever we are, we create arenas of struggle.”

Pickens and Davis’ conversation ranged widely, from the continuing relevance of Are Prisons Obsolete? to former President Obama’s views on defunding the police to the importance of self-care amidst the stresses of civic betterment.

Asked how she views the professor’s role, Davis replied, “I see my role as a teacher as helping students to generate questions…about our lives, questions about the conditions in which we live. And of course, one doesn’t have to go to a university to acquire that facility.”

In fact, she pointed out that people behind bars are often the people raising the issues most germane to the prison debate (and that those concepts are sometimes appropriated by scholars).

“Part of teaching, I think, is to teach students that knowledge gets produced in so many ways and so many places. And that because we happen to have been exposed to professionalized modes of producing knowledge, that does not mean that we are the best, and does not mean that we cannot also learn from those who do not have the capacity or the ability to engage in these professionalized processes.”

As one student asked during the Q&A that concluded the keynote, is Davis optimistic about prospects for change rooted in the unprecedented protests last summer in response to the police killings of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and others?

It’s too soon to tell what those prospects might look like, she replied. “We often think that radical change gets represented by mobilizations, and of course mobilizations are important. It was extremely important to witness the fact that huge numbers of people, more people than ever before in the history of this country, more white people, under conditions defined by the COVID-19 pandemic, demanded that we move in a different direction.”

“We’re at a point now where we can begin to do that work of bringing about change within organizations, within institutions.”

Yet, she continued, “we’re in the phase now of actually doing the material work that can institutionalize change, and the results of that will not become evident immediately.”

She added, “We can only hope, and we can only encourage colleges and universities like Bates to look at their histories and begin to recognize the ways in which they have contributed to the structural racism that, we learned during this period, is so much more important than the individual’s expression of racist ideas.

“We’re at a point now where we can begin to do that work of bringing about change within organizations, within institutions.”

Also taking part in the keynote event were the co-presidents of the Bates College Student Government, seniors Perla Figuereo and Lebanos Mengistu — who, in their welcome, asked the students among their viewers to reflect on what activism means to them. A third senior, Bates Black Student Union President Joshua Redd, formally introduced Angela Davis, and moderator Vice President for Equity and Inclusion Noelle Chaddock introduced Pickens.

Doug Hubley is a writer and musician living in Portland, Maine.