To Marshall Hatch Jr. ’10, the long painful moment in American history that is 2020 feels like Reconstruction revisited. Lately he’s been delving deep into the history of that period after the Civil War, “which at once was the highest high for African Americans,” he says, “and then the lowest low.”

In that era, Blacks held seats in Congress and in Southern legislatures, but angry white Southerners inflamed racial tensions — chaos coupled with hope, American democracy at stake.

“The question during Reconstruction was, ‘What kind of country do we want to be?’” Hatch says. And the question arises again today. “These are incredible times to be living in,” Hatch says. “But there’s a lot to be dismayed about.”

Nationwide, the pandemic still rages, along with the streets. Racists are emboldened, but their opponents shout back. And in the West Garfield Park neighborhood of Chicago, where Hatch grew up and works now as an activist and community leader, 2020 thus far has marked a period of terrible lows.

There were loved ones lost to COVID-19, including his Aunt Rhoda, the matriarch of his father’s side of the family. She was the organist at New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, where his father has been pastor since 1993 and which serves as home base for Hatch’s community work.

There were more names added to the nation’s long list of Black people killed or shot by police with no justification. When Hatch recites the names of murdered Chicagoans — he knows them all, it seems — it sounds almost like a prayer, or a sorrowful poem. But then came a new verse from other cities: George Floyd. Breonna Taylor. Jacob Blake.

“There’s a lot to be done on the ground and in the community,” Hatch says. “And a concerted mobilizing effort nationally to decide what kind of country we want to be.”

In the late spring he spoke at protests. In the summer he watched as looting and fires damaged the neighborhood he’s trying to rebuild. The Family Dollar store down the block burned, which further parched the food desert of West Garfield.

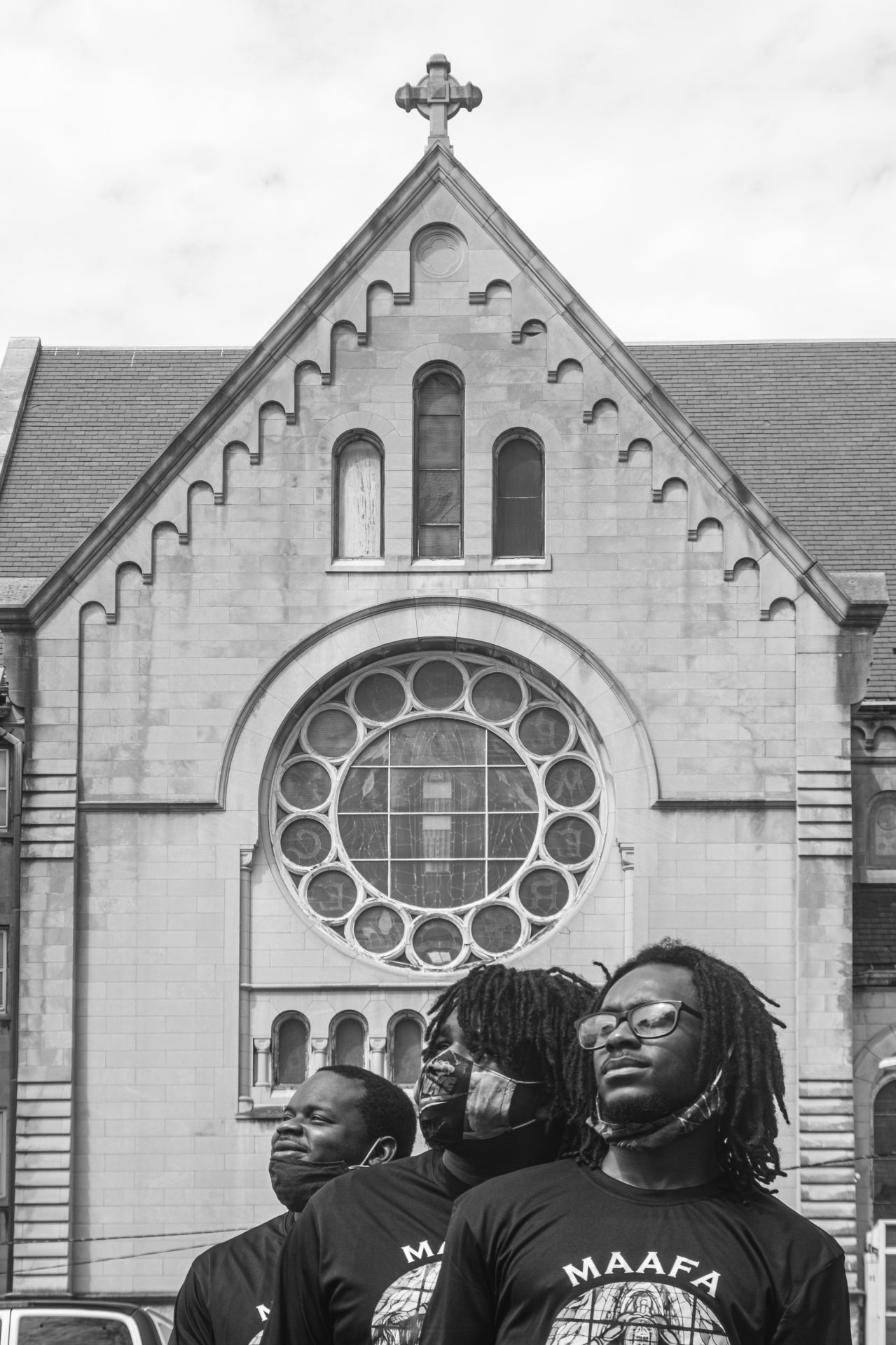

The pandemic made it harder to connect as much as he wanted with the young men of color in the job and life-skills training project he co-founded and runs, the MAAFA Redemption Project. (“maafa” is a Kiswahili word meaning “a great disaster or terrible occurrence.” It describes the transatlantic African slave trade and all that it wrought.) These are young men, some with criminal records, all at risk, finding their feet again or for the first time, who need connection and touch, for whom social distancing might feel like yet another alienation.

As the pandemic tightened its grasp on Americans of color, the MAAFA group, 33 strong in its fourth group of trainees, met in masks, in smaller groups, and outside, learning practical skills, from financial planning to the building trades.

In between, Hatch went for bike rides when he could, listening to an audiobook, David W. Blight’s fat, Pulitzer Prize–winning biography Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom as he pedaled, thinking about the way Reconstruction was thwarted, how the South turned to Jim Crow laws to enforce its systemic racism, as his ancestors fled to the North. “It went back into an anti-democratic republic,” he says. “That’s the principle that I’ve kind of been mulling over lately: Maybe progress is not what you gain. Progress is simply what you keep.”

But in contrast to the bad news, 2020 has also brought Hatch personal and professional highs: a baby daughter at home; the empowering discovery of an ancestor who fought for the Union in the Civil War; and the intervention of a benefactor so famous she is known by only one name.

In April, after Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot spoke publicly about the disproportionate impact COVID-19 was having on communities of color, and news media covered the community’s heartbreak over the loss of Rhoda Hatch, Oprah Winfrey asked to meet Hatch and his father, the Rev. Dr. Marshall E. Hatch Sr.

Although he is as level-headed as a human could be, Marshall Hatch Jr. does admit to having been nervous about talking to Oprah, even over Zoom. “I didn’t want to fumble over my words.” In the end it was, he says, like talking to a family member. “She is just so personable. You have to love her.”

Winfrey subsequently announced a $5 million gift to establish Live Healthy United, a community-based initiative directed at providing food, contact tracing, personal protective equipment, and wellness checks to Black and Latinx communities. The MAAFA Redemption Project is one of five Chicago groups working under that umbrella.

“It’s almost like, unwittingly, I’ve been preparing myself for moments like this, if that makes sense.”

Twice a month this summer, Hatch oversaw food giveaways in the parking lot of the church, boxes stuffed with fresh vegetables and fruit as well as dry goods, with hundreds more boxes delivered to homebound seniors nearby.

With Winfrey’s philanthropy, that work can go on for two more years. “The pandemic isn’t going anywhere,” Hatch says. This is seed money. More will be needed. “She said just as much.”

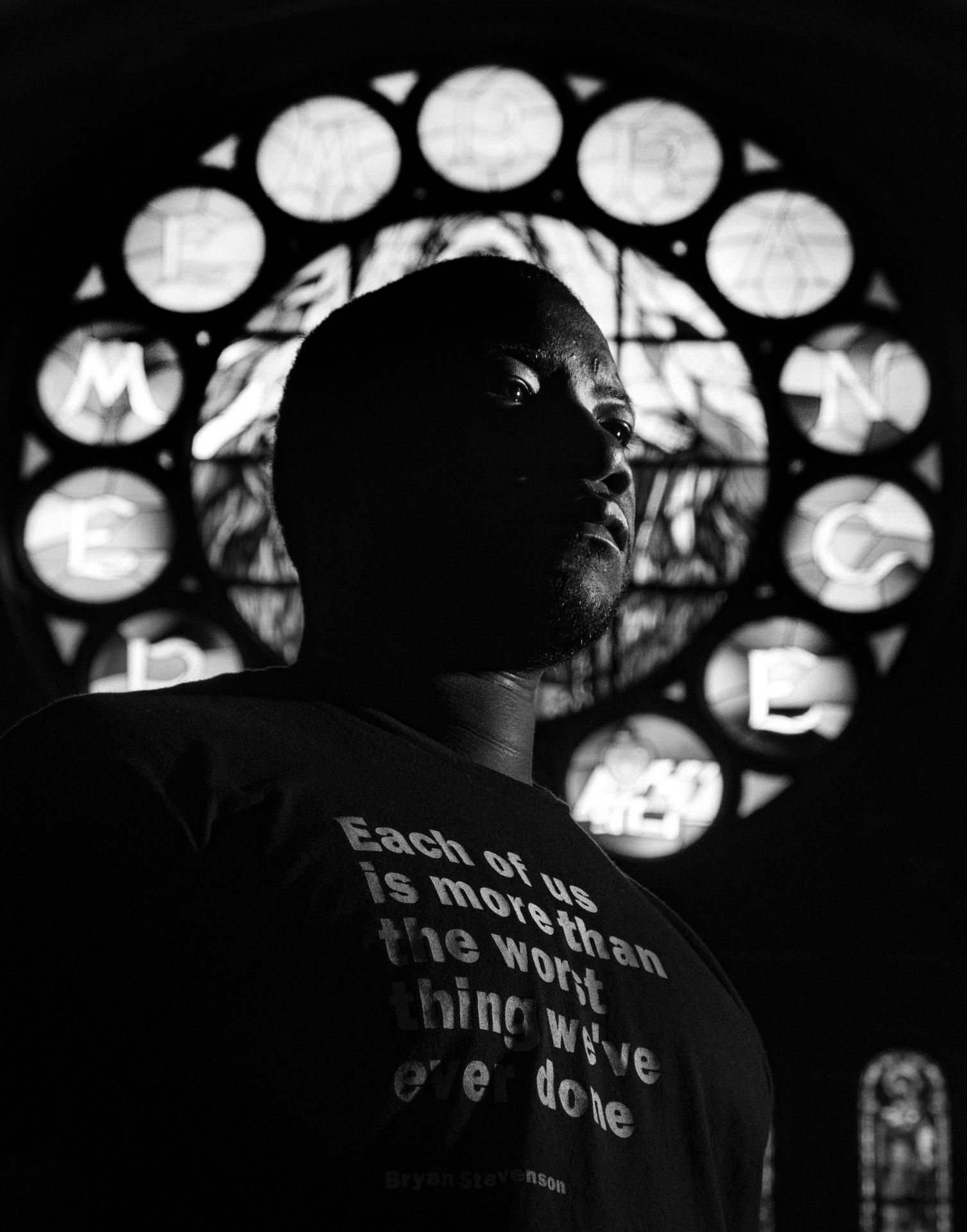

Hatch speaks in soft, warm tones, sitting in the dark of his father’s church, talking into a laptop with a quiet grace that all but lifts the veil of Zoom’s technological separation. Sometimes he looks up at the stained glass windows of New Mount Pilgrim when he talks, when he’s thinking (he’s always thinking).

“This is really a part of the legacy of what it means to be Black, what it means to be on the West Side of Chicago in a forgotten neighborhood. I mean, it’s just, it’s almost what we’ve been created or designed to do,” he says. “To resist and to inspire and to build.

“It’s almost like, unwittingly, I’ve been preparing myself for moments like this, if that makes sense.”

For those who knew him at Bates, what Marshall Hatch is doing today makes complete sense. Charles Nero met him as a first-year in his “Introduction to African American Studies” course, which Nero and his husband Baltasar Fra-Molinero were co-teaching. “We were very impressed,” Nero said.

Then Hatch showed up in Nero’s course “White Redemption: Cinema and the Co-optation of African American History.” Nero remembers showing the students the 1998 movie Bullworth, in which Warren Beatty plays a cynical politician whose career is revitalized when he starts rapping and imitating Black people.

Charles Nero points to an expression from the playwright Lorraine Hansberry: “Committed amid complexity.” And, he says, “That is Marshall.”

“The movie ends with him proclaiming his authenticity, and right after that he is shot,” Nero says. After the screening, Nero asked his students, “Do you recognize this moment?” The class was stumped. Not Hatch. “He says, ‘That’s a reenactment of the assassination of Martin Luther King,’” Nero remembers. “I said, ‘Exactly,’ and the class — everybody looked at Marshall.” He laughs at the memory. “Marshall is brilliant and in ‘White Redemption’ it was just simply confirmed.”

Nero places Hatch in the tradition of Paul Robeson, the musician, actor, and activist from the first half of the 20th century. “The scholar, the athlete, the activist,” Nero says. “You can’t position one above the other. He is all of them simultaneously. He does all of them well. He is a model of a term we like to toss around: intersectionality.”

Nero points to an expression from the playwright Lorraine Hansberry: “Committed amid complexity.” And, he says, “That is Marshall.”

At Bates that complexity included his commitment to intellectual pursuits, far from home, while also being a varsity athlete. But the complexity also included an unwelcome surprise: feeling out of place in the college that had educated Benjamin Elijah Mays, Class of 1920, whose legacy had drawn Hatch and his father — both of whom have the middle name “Elijah” — toward Bates. And as a Gates Millennium Scholar, he’d had many other options, including a Historically Black College.

“My freshman year I was a distinct minority, and I felt it,” Hatch says. At the time, the percentage of U.S. underrepresented minorities at Bates was less than 10 percent (it’s now 25 percent). One of the handful of Black students in his class was Anthony Phillips. The two met in Nero’s African American studies course and became fast friends, spending late nights listening to Coltrane and Donny Hathaway, “all the while talking about what we are going to do when we leave Bates to improve our neighborhoods,” Phillips says. Borrowing a van from Dean James Reese so they could drive to the church Hatch had found 20 minutes away, with stops at Denny’s in Auburn. Phillips dropping by Hatch’s room to talk about a girl and finding his friend watching the 10 o’clock news, or reading. “Always reading.” Holed up in Pettengill, working on papers that were due in the morning, even when bed was calling to Phillips. “Doc, sleep is the cousin of death,” Hatch would tell him.

But first, Hatch had to be persuaded to stay at Bates, and Phillips tried. “He was ready to go,” Phillips remembers. “It was disappointing to him to see the lack of diversity.” In the end it was Hatch who persuaded himself to stay. He’d picked up Born to Rebel, Mays’ 1971 autobiography. He read the much-quoted sentence: “Bates College did not ‘emancipate’ me; it did the far greater service of making it possible for me to emancipate myself and to accept with dignity my own worth as a free man.”

“I internalized those words,” Hatch says. “It was the words of Ben Mays that allowed me to remain hopeful.” He joined in as other Bates students began organizing to protest the lack of diversity. Soon Hatch was urging Phillips to join him.

Phillips had come to Bates from Philadelphia, where he had been one of just seven Black students at LaSalle College High School, an elite Catholic preparatory school. He’d been on diversity and inclusivity committees there. He told his friend he’d done this work already, that he was “really trying to create a new life” for himself at Bates.

But Hatch said to his friend, “There is no better time to do right than now. We have to do something. Our school needs us.” Phillips, now the executive director of Youth Action, a Philadelphia-based nonprofit that builds youth leadership through civic engagement and service, remembers Hatch as a galvanizing presence in the effort, always avoiding being a focal point but still managing to be a fulcrum.

That was how it was on the basketball court as well. In those early days at Bates, Hatch headed over to Alumni Gym to work out his stresses, often with Jon Dowdy ’09, a childhood friend from Chicago who had encouraged him to come to Bates. “It was a sanctuary,” Hatch says. “I was a gym rat.”

Declining the word “star,” Hatch says that playing basketball growing up kept him out of “the trick bags of inner city life.” As Hatch practiced, he caught the attention of Jon Furbush ’05, then a new assistant coach and just fresh out of Bates himself. “I didn’t know the recruiting class because I was new to coaching, but I thought, ‘Who is this kid? He’s got to be one of the top prospects.’”

As it turned out, Hatch was not a recruited athlete, but by the time Furbush returned to Bates to take the head coach job after getting a graduate degree, Hatch was a junior, captain of the team and a fluid player with “an uncanny ability that no one else had to create his own shot.”

There were back-to-back Hatch 3-pointers in the course of 11 seconds that sent a game with Colby into overtime. “The gym was nuts,” Furbush says. Video from the game shows Hatch emerging from the jumping and hugging masses, going quietly, with no fuss, to the bench, ready for overtime. “He never gets too high or too low,” Furbush says.

A decade later, as Bates went to remote learning over the spring, Hatch became a regular sounding board on Zoom for Furbush’s current team as they struggled with being cut off from campus and each other because of COVID-19. Furbush describes Hatch as invaluable, especially for players of color. “One of the most authentic listeners I have ever spoken to,” Furbush says. He offered up his own ear for Hatch after George Floyd’s murder. “I wrote to him to say, ‘Hey man just thinking about you. You are somebody who has always put everybody else before yourself. It’s okay to be selfish.’”

Basketball was one of the factors that helped Hatch make a home for himself at Bates. So was singing with the Gospelaires, the gospel ensemble he co-founded; being active with Amandla! Black Student Union; and actively mentoring younger students of color, helping them feel comfortable on campus. “He was a central convener,” Phillips says. He made connections with Admission staff, including Carmita McCoy, at the time a dean who had begun recruiting for Bates in Chicago. She found herself using Hatch as a sounding board. “I picked his brain quite a bit,” McCoy says. “He was a huge recruitment tool,” and he knew Chicago. “There were quite a few that came to Bates on Marshall’s word that they would be OK.”

Hatch was also spending time, along with Phillips and other friends, at the Multicultural Center on Campus Avenue, known informally by students as the Black House. “We would cook there, we would sing songs at the drop of a hat,” he remembers. “It was a space that felt like home, like a reprieve from a dominant culture on campus where you were forced to question yourself before even opening your mouth, out of fear that you would sound dumb or be too renegade with your ideas.”

Hatch attends the Class of 2010’s Baccalaureate on May 30, 2010. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

In July 2010, Hatch, having graduated with a politics major, joined Bates Admission. At the same time, Bates restructured its equity and inclusion programs, which included renaming the Multicultural Center as the Intercultural Center, recasting its programming as the Office of Intercultural Education, and the departure of a popular administrator.

The goal was a broader approach to equity and inclusion, but it was a dispiriting time for Black students and recent alumni like Hatch, who felt that valuable support and an important space — the “reprieve from the dominant campus culture” — had been taken away. “Bates did not do a good job with that,” he says. (Today, the Office of Intercultural Education’s program space is in Chase Hall, and a Senior Staff–level vice president leads equity and inclusion initiatives.)

As an Admission counselor, Hatch visited cities like Seattle and San Francisco, working to make Bates a place where students like him could be comfortable. McCoy got a chance to mentor him then, not that he needed much of it. “He was top-notch,” she says. “A consummate professional, a funny guy, very respectful…a gentleman and a scholar.”

But love called him back to Chicago. He wanted to make sure his little brother was being supported in his adolescence. He took a job at Urban Prep Academies for three years, where he reconnected with a Bowdoin alum, Zulmarie Bosques, whom he had met once in Maine, and they fell in love (they married in August 2018 and have a 1-year-old daughter, Sophia). He went back to school himself, earning two more degrees, a masters in social work and one in divinity from the University of Chicago, finishing in 2017.

In returning to Chicago, he also returned to his spiritual home, the New Mount Pilgrim Missionary Baptist Church, where his father has been the pastor since Marshall Jr. was 5. “I grew up in the church,” Hatch says. “It has nurtured me. It has nourished me. It really is all that I know.”

The church and its associated buildings in the surrounding streets are the spiritual and physical home of his MAAFA Redemption Project, which he and his father co-founded in 2017. New Mount’s sanctuary was once the home of one of the largest Irish Catholic churches in Chicago, a somber neo-Gothic building of soaring arches and Carrara marble, with massive stained glass windows filled with Eurocentric-images of Jesus and Mary. In short, when the archdiocese sold it to New Mount in 1993, it was a very white place.

The bones of the place remain, but its eyes, in the form of its stained glass windows, have gradually been replaced with imagery that speaks to African American history and iconography. The job is nearly done, and the windows stand as symbols of what was and what Marshall Hatch Jr. hopes will be, not just for this predominantly Black community in Chicago, but others all around America.

Via Zoom, he gives a tour, enabled by a laptop tilted this way and that. The North Star–Great Migration window features a male figure lifting his daughter up to the next generation, inspired by the seminal scene from the 1977 miniseries Roots, where Kunta Kinte holds his baby daughter up to the sky.

“It speaks to the promise and pain of the African American community,” Hatch says. “Particularly the journey from the South to the North.” Some elders of the church were part of that Great Migration, from states like Arkansas and Georgia. Hatch’s grandparents were also part of the mass movement of Black people fleeing the Jim Crow South after Reconstruction. “They came up from Mississippi,” Hatch says. “Aberdeen.”

Rhoda Hatch was the keeper of those family histories. When she died on April 4, at 73, after a terribly swift battle with COVID-19 — “my father took her to the hospital and never saw her again” — stacks of documents came to him, along with a calling to find out more. He joined Ancestry.com and discovered that his great-great-great-grandfather, Zack Hatch, served in the Union army. This knowledge gave him a deeper sense of belonging. “I am just as American as anybody else.”

Hatch poses before a stained- glass window that spells “Remembrance” within New Mount Pilgrim Baptist Church, the home of his community work in Chicago’s West Garfield neighborhood. His T-shirt has a Bryan Stevenson quote: “Each of us is more than the worst thing we’ve ever done.”

(Sebastián Hidalgo for Bates College)

The Sankofa Peace Window features images of the four girls killed in the 1963 church bombing in Birmingham. Five images of young martyrs of Chicago’s violence line the bottom. “Sankofa” refers to a principle of using the wisdoms of the past to imagine and project a better future. “It’s almost like a philosophy of life,” Hatch says. (Sankofa is also the name of the annual Bates show that explores the experiences of the African diaspora through theater, music, and dance.)

“The East window is kind of hard to see,” Hatch says, tilting again. “That is the MAAFA Redemption window.” Composed of grays, blues, and black, the figure of Christ stands, head back, arms open to the sides, but chained. His torso is represented by a slave ship, bodies packed in like firewood, similar to the illustrations by British abolitionists in the late 18th century, which, as Hatch says, “were created to be a broadside to expose the horrors of the transatlantic slave trade.”

In this depiction, Christ is “carrying within himself the memories of those who lost their lives on the journey to America,” Hatch says. “But also he’s carrying the legacy of those who survived. And we are that living legacy.”

Hatch wrote about this window and how it inspires the New Mount congregation for his master’s thesis in the divinity program. It is foundational for him as well. “I’m really committed to do something to not repeat that history,” he says. “To redeem that history by living out a conscious life, a life that’s impactful.”

When the Hatches, father and son, founded the MAAFA Redemption Project, they were thinking of Laquan McDonald, a 17-year-old shot and killed in 2014 as he walked away from Chicago police. The U.S. Department of Justice had just released a report on Laquan’s killing, describing the culture of “excessive violence” within the Chicago police. “The creation of MAAFA in 2017 was a way of protesting,” Hatch says. “That was part of the motivation for finding the Laquans in this community and trying to invest in them and create spaces for them to heal and grow.”

“We try to instill in them a sense of dignity, respect, hope — telling them that this rich history that you are a product of is what gives you purpose in life,” Hatch says. “Those who came up from the South, those who literally sacrificed their lives so that you could be alive right now, you owe them something.”

The main focus for each MAAFA cohort (the size has grown steadily since the first class of 12) is on learning construction trades. They’ve already rehabbed two abandoned buildings, and this year Hatch and his advisers, many of them elders from the church who work in construction or finance, added training for landscaping jobs.

The symbolism of both is not lost on Hatch, he says. “We started on the assumption that construction-based training would be ideal. Again, symbolically, you have to tear down to build up. And I think horticulture is even more impactful.” The trainees understand the potential, for them and their community. “It doesn’t take much to convince them that there is a huge industry behind beautification.”

They’ve been creating an urban farm and a meditation garden in the yard of the Sankofa House, where about half the trainees live (COVID-19 has slowed some housing plans because of social distancing). There will be a fire pit, a place to talk, a place to share the learning of the day. There are, Hatch says, “endless possibilities” for the men of MAAFA.

Anthony Phillips agrees. He recently made a financial commitment to support MAAFA. He saw firsthand what West Garfield is up against, when he stood up for Hatch at his wedding.

“I grew up in North Philly,” Phillips says. “With poverty and everything, but I will tell you, that community? It is no comparison. It is much more in need.” He recalls seeing a video of a 24-year-old getting his GED and thanking Marshall for it. “What Marshall is doing is taking those kids who people forgot about. He is positioning them for success. And he also doesn’t forget about the grown men who need it. That is huge.”

What about the possibilities for him? Hatch is the kind of person who seems like he could be, say, a natural politician. He smiles. “Not long ago, I was extremely pessimistic about politics,” he says. “So much so that I considered it an evil.”

Some things have changed that view, including the legacy of the late civil rights icon John Lewis, and getting to know Illinois Congressman Danny Davis. “His heart,” Hatch says. “His work.” But he knows a minister can do great and important work as well. “If I had to decide in this season of my life, I would edge toward ministry.” This work he’s doing now? “I can’t imagine being more fulfilled.”

The other day, Hatch father and son were talking, and they found themselves “dwelling on despair.” As they spoke, they came to a resolution, of sorts. “Because of who we are, because of the lineage that we represent, and because of the God we believe in, we can’t really afford to linger in despair. Optimism is where we should land, I think, because there’s a lot to hope for.”