The eight seniors participating in this year’s Annual Senior Thesis Exhibition opening May 7 have produced work that reflects on the ephemeral qualities of humanity, some of it created in mediums chosen in part because of the restrictions of COVID-19, and much of it with heavy emphasis on nature, from its most essential cellular level to the beauty — and utility —of landscapes.

Fittingly then, these studio art majors’ work in video, animation, ceramics, and photography reflects what life in this academic year has been so far: complex, challenging, and requiring flexibility. But beyond that, what permeates the exhibition is a sense of gratitude. For one thing, these Class of 2021 studio art majors, whose thesis work has been advised during the Winter term by Associate Professor of Art and Visual Culture Pamela Johnson and last Fall by Lecturer Susan Dewsnap, get to have a physical show at the Bates College Museum of Art, after the pandemic forced a virtual exhibition last year.

There won’t be a lot of fanfare — the pandemic means no usual campuswide opening reception at the museum — but for the artists who are on campus, there will be a chance to walk with friends and family through the exhibition space.

This slideshow displays examples of the eight Class of 2021 studio art majors’ work in video, animation, ceramics, and photography; portraits of the artists are below.

And already, as Laila Stevens ’21 of Norwich, Vt. recounts, there has been a sense of relief and joy. “I am extremely happy that we get this exhibit,” says Stevens, who works in ceramics. “I felt quite bad for the seniors last year.”

She and her classmates gathered in the museum recently to begin a vital part of the thesis, the experience of mounting a show in a professional setting. “We were setting up the furniture and laying out a lot of the photographs,” says Stevens. “It was a really fun process.” (The museum is familiar territory for Stevens, who has been an intern there all year, focused on receiving and researching a large donation of Maine art from the late Jane Costello Wellehan ’60.)

Stevens’ works will be mounted on pedestals. Like her fellow ceramicist and studio mate Christopher Barker ’21 of Burlington, Vt., who cites photos of deep space and microscopy shots of biological specimens such as viruses, insect wings, and neuron networks as inspiration, Stevens’ art is fed by her studies in science; she was pre-med before switching to an art track as a junior.

She relies heavily on biological imagery for her inspiration and was initially drawn to creating representations of the COVID-19 virus. Over the course of the year, though, her work became more amorphous. “People have told me they remind them almost of bones under skins. I have very skeletal influences, which I think were almost subconscious.”

Beyond science, Barker’s work is inspired by American artists Terry Winters, Jasper Johns and Brice Marden. “I found myself falling into the vacuums present in their abstracted drawings and painting,” he says.

Barker has integrated those influences onto the ceramic surfaces, aiming “to pull the view beyond the solid, hard exterior and into the realm and space created by my marks.”

For Alex Paton ’21 of Charlotte, Vt., each of his utilitarian ceramic vessels synthesizes his evolving relationship and scientific inquiry into clay, and represent “inherent material life beyond the control of my touch.” They are solid now, and represent “a product of my hands and mind, but soon, they too will be weathered, broken and quietly cast away.”

Use of video that explores family history is a striking theme in this year’s exhibit. Against a backdrop of archival news footage from pre- and post-revolutionary Iran, Eli Eshaghpour ’21 of New York City uses the voices of his grandmother, uncle, and a distant cousin as a medium for an oral history of both his immediate Persian Jewish family (his grandparents immigrated to Jersey City in 1970) and family who stayed behind and lived through the revolution.

Each relative was born in a distinct political climate in Tehran, and Eshaghpour uses them in his film But at Least We Remember to produce “a testament to the randomness of history and its subsequent effects on individuals’ experiences, memories, and self perceptions.”

After receiving a Stangle Fellowship last year, Eshaghpour thought he’d be able to travel, including to Los Angeles to meet, photograph, and interview other, distant relatives who are more involved in the Iranian diaspora. “But COVID changed that,” he says.

Instead he uses audio recordings of his family members’voices, their scratchy tonality melding with archival film footage. Interspersed sporadically in his film are images of cellular activity, inspired by footage that Laila Stevens, his fellow studio art major, shared in a class.

The footage looked cool, he said, but it also struck him that he could connect the lymphatic cancer of the last Shah of Iran to both his own family and the time he’s living in. “No one really knows how much the cancer played into the Shah’s decision making,” Eshaghpour says.

The footage, plus conversations with his family, prompted a metaphor “about our immune systems, and how free speech and protesting can be part of a country’s own immune system — a protector of freedom that can heal a sick country.”

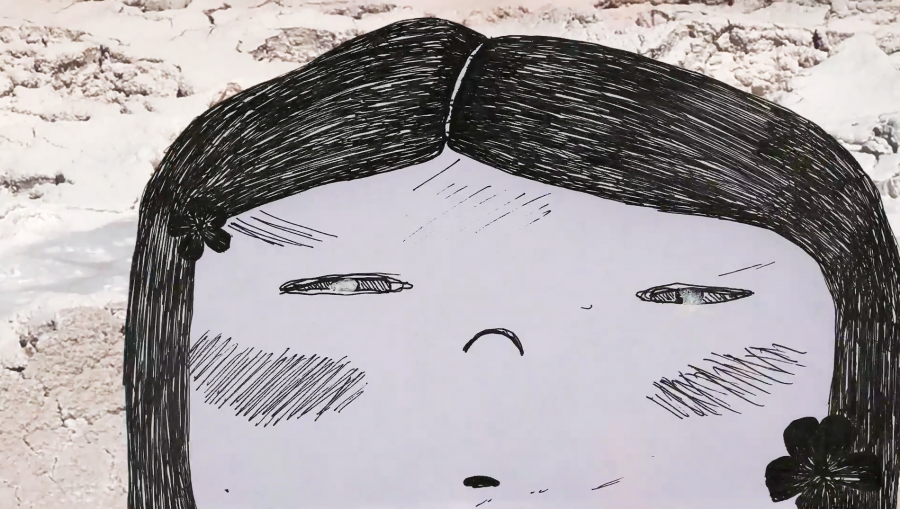

For Mari Sato ’21, of McMinnville, Ore., “animation has become my escape.” It’s helped her navigate uncertainty. “I read, watch, and listen, as I go about my life with my art in mind. In the mornings, after drinking coffee and considering the day ahead, I go to the studio or to my desk, and I pick up a pen.”

The results are a short film called Sakura, a playful mix of animation and live-action video from footage she’s taken at and away from home, including audio from feral cats meowing in Indonesia. “All are sentimental,” Sato says. “I focus on the feelings they emit.”

Wenjing Zheng ’21 has been studying remotely from home in Wuhan, China, and her five-minute experimental, highly naturalistic film Old Home is heavily influenced by legendary French filmmaker Agnes Varda as well as Zheng’s own deep exploration of her grandparents’ lives in Qiankeng Village, the “old home,” a Chinese idea that describes “the place where your family and previous generations originated.”

She spent days walking on her grandparents’ farmland, learning how to identify every plant “and understand how much effort my grandparents exert on them.” She had imagined that this rural area, where all the residents wake at 6 a.m. to begin their farmwork, would be relaxing and tranquil. “But it turned out things were not as I assumed. It is a plain life, a cycle of waking up, working, and going to bed. Many scenes of my video show the repetitions of cooking and gardening.”

There are two still photographers in the exhibit, Carlo Cremonini ‘21 of Cambridge, Mass., and Blaise Marceau ’21 of Waban, Mass.

Marceau’s images join landscapes with figures, mixing realism and artifice, trying to create a sense of mystery and narrative. He fills his spare time with mountain biking, hiking, fishing, and camping in Maine.

“Capturing the natural beauty of the wilderness through photography goes hand in hand with my passion for the outdoors,” he says. His spin on the form is to keep the identities of his subjects hidden. “This puts more focus on the figure as a whole.”

Cremonini has traditionally worked in 35mm film photography. In fact, the digital course he’s taken during the final semester of his senior year is the first non-analog course he’s taken. But his thesis work is focused on pinhole photography he began while at home in Cambridge last spring after his study abroad program in Florence shut down.

“Very much a product of the times,” he says. “I no longer had access to a darkroom.”

He could set himself up with little more than a camera built from materials at hand (a paint can works well) and make his prints in a closet. Displaying this work from equipment that could cost only $30, rather than meticulously processed and printed work from 35mm film, is a form of advocacy. “This feels a little bit more like guerrilla photography, which I like because the barrier for entry is very low.”

Carlo Cremonini

He appreciates the kind of images it yields. “You get this kind of blurriness,” he says. “You get these expressions because people are stuck in time, so there is this kind of reminder of the past, those old photographers where people look very posed and serious, but of course the subjects are very contemporary.”

He’s presenting the work in its negative form, and asking viewers to use their smartphones to invert them (under accessibility settings). And Cremonini is looking forward to having a chance to interact with visitors to the museum, just in case they fumble with those settings, and or better yet, want to talk about the art. “I think I would get a lot out of hearing people’s feelings about the work.”

For this art born out of a time of isolation and confusion, ending on a note of connectivity is truly a reward.