One of the earliest memories Tiauna Walker ’21 has is of walking into her father’s dorm room at Bates. “It was a very small room,” she says, specifically a single, with a twin bed, extra long. And there was one of the now-laughably large computers of the era: “This like, huge box computer.”

Listening to his daughter describe the scene, Ed Walker ’02 squints against the late-winter sun in front of Hathorn, trying to summon up his own mental snapshot. “It had to have been Hedge,” he concludes. That’s where he lived senior year, when Tiauna would have been 3 and visiting the campus with her mother.

There may be another Batesie who’s had the distinction of having watched her dad play basketball in Alumni Gym, or who’s gummed french fries at the Den with baby teeth while her dad was in class. Though if not unique, Tiauna Walker’s Bates roots are undeniably rare and unusual; she was welcomed into the Bobcat family on the very day she was born.

Bates Magazine

This story appears in the spring 2021 issue of Bates Magazine.

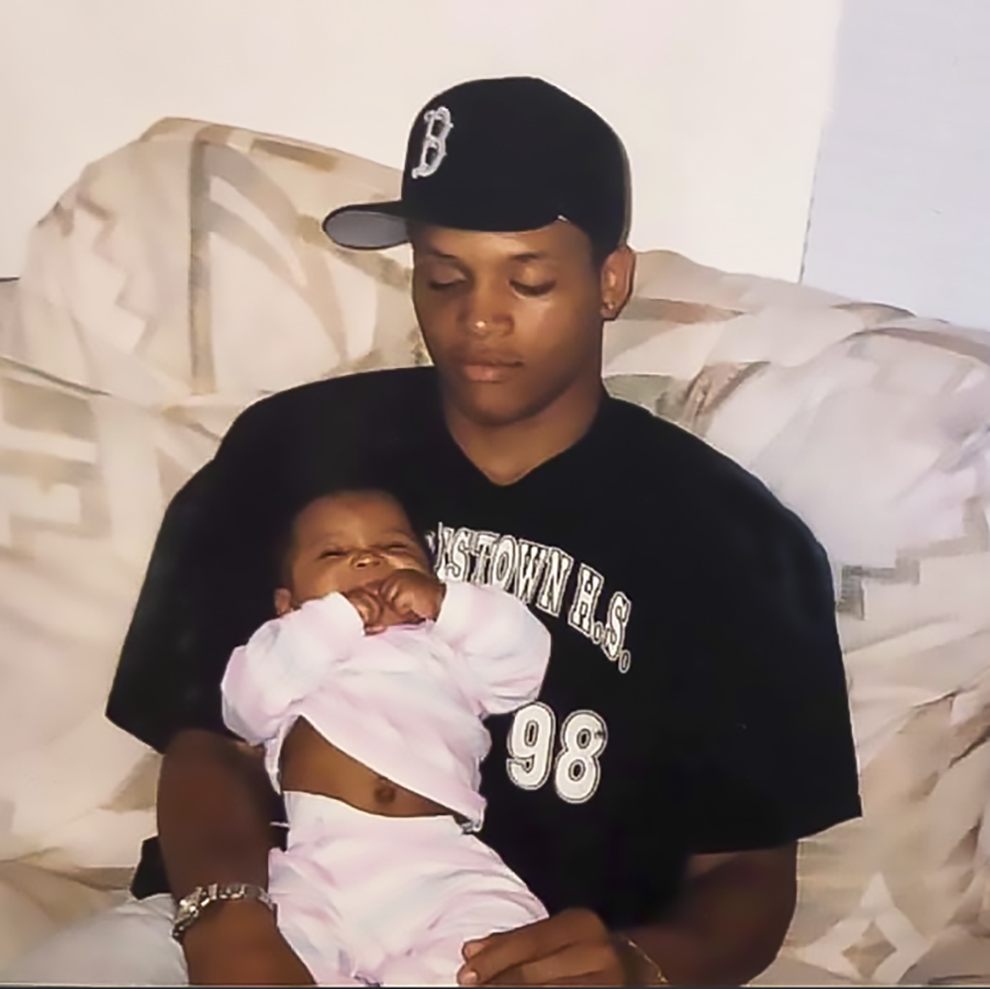

Her middle name is Divine. “Divine intervention,” Ed Walker says. “Which is what she was.” The baby and Bates changed his life at roughly the same time. Just starting his second semester at Bates when she was born, he chose her middle name as a reminder to himself.

Her first name was plucked from the lyrics of the Notorious B.I.G. song “My Downfall,” in which the rapper sang of his own daughter: “Apologies in order, to T’Yanna my daughter / If it was up to me you’d be with me.”

Walker picked the name Tiauna as a sign of his commitment to being present, because at 19, the last thing Ed Walker wanted to be was an absentee father.

He had arrived at Bates in late summer 1998, a bright prospect from Roxbury, Mass., with not much more than the clothes on his back. He was 19, smart, charismatic, a gifted musician, and a leader on and off the basketball court. But he had been through a tumultuous childhood.

Joe Reilly, then the new head basketball coach at Bates and only 29 himself, had recruited Ed Walker from Charlestown High in Boston, where Walker played for Jack O’Brien, a Massachusetts coaching legend who had a reputation for guiding his players toward college opportunities.

As Reilly got to know his recruit, he understood that Walker was food- and housing-insecure. The youngest of seven, Walker was bouncing from house to house, often sleeping at his high school teammates’ houses. “He called it ‘house hopping,’” Reilly says.

“I spent a lot of time looking for housing,” Walker agrees. The Charlestown team was his sole source of structure and a true fellowship, albeit one rooted in shared struggle. “Many of my friends were taking care of their younger siblings,” Walker says. “We had to work together to find dinner together.”

“And that’s when I felt human again,” says Walker. “I knew that he was invested in me and not just basketball.”

Charlestown High was close enough for an easy day trip and Reilly formed a bond with Walker over at least a dozen recruiting trips. But the regular phone calls from the coach were particularly vital for Walker. “He asked about life and my circumstances and he never once mentioned basketball,” Walker remembers. “And I saw value in that.”

One day, as Walker recalls, Reilly said this to his young recruit: “If you come to Bates, you have my word. I’m going to see that you cross that stage, whether you play basketball or not.”

“And that’s when I felt human again,” says Walker. “I knew that he was invested in me and not just basketball. I knew that if they said yes, I would say yes.”

He remembers being very emotional during his interview with the Office of Admission in December. Katie Moran Madden ’93, then an associate dean, asked him a question he didn’t understand, about AP classes. “I didn’t even know what an AP class was,” he says. So he bluffed, and then, as he realized his misstep, broke down in tears. “I was really young and raw.” Madden, who now works in admission at Dartmouth College, doesn’t remember tears, but she does remember how genuine Walker was. “And also vulnerable.”

Still, the conversation convinced Madden that Walker was ready for the challenge that Bates would provide. “I remember just being blown away after meeting him,” Madden says.

Joe Reilly was relieved. He had been worried about what would happen to Ed Walker after high school. The players he coached in the NESCAC usually had options. Family to fall back on. Not Walker. “Bates was his only safety net,” he says.

But by late spring of Walker’s senior year at Charlestown in 1998, there was another layer of complexity. His high school girlfriend, Starkia Benbow, was pregnant. For some this might have meant staying in Massachusetts, even giving up the dream of college. But for Walker, the promise of Bates took on a whole new meaning. “It was in that moment that I knew: Now I have to make something of myself. I have to think about someone other than myself.”

“His vision was, if he was going to be the best provider and the best dad he could be for Tiauna, he had to get that Bates degree,” Reilly says.

“His vision was, if he was going to be the best provider and the best dad he could be for Tiauna, he had to get that Bates degree,” Reilly says.

Walker asked for a single room at Bates, so that mother and his soon-to-be-born child could visit, not a request first-year students could count on. “Bates was extremely supportive,” he says.

But initially, he didn’t exactly fit in. “Everything about me was different,” Walker remembers. “My attitude. My style of dress. The language I spoke, the slang that I spoke. It was very clear. I understood that right away.”

And like many other Black students who’ve arrived at Bates, Walker quickly saw white supremacy in action. On his first day, moving into Hedge Hall, another student assumed he wasn’t a Bates student and confronted him. “Essentially asking, what was I doing there? Like, ‘Why are you here?’” Walker told the other student, “I’m here to be a student.”

That day Joe Reilly dropped by Hedge and found Walker still fuming about the incident. “He was wearing a Carolina Panthers NFL authentic jersey,” Reilly remembers. The room was sparse. “Ed came with very little.” He talked his new player down, but he never forgot that window of insight he got into the stark reality of being Ed Walker. “There were a lot of things you forget over 23 years,” Reilly says. “That’s not one of them.”

Reilly, now the head basketball coach at Wesleyan University, checked in with Walker before sharing that story. It felt too private not to. “I don’t want it to seem like Bates was not a welcoming place for Ed because I think it really was. But there were some challenges for Ed and students like Ed. I’m really proud that, in my 11 years there, great progress was made. Bates was a great place when Ed got there. It really was. And it was just a better place when Ed left.”

Teammate Billy Hart ’02 had never heard that story. He shakes his head at the telling, saying he and Walker talked about a lot of things, but not about such big-picture issues as being Black at Bates. “I feel bad that I probably never even asked the most simple questions,” Hart says. “Which is the privilege I had and he didn’t have.”

Hart says Walker brought a unique kind of maturity to Bates. “If anything, he thrives and is able to focus and do better in uncomfortable situations. He had a mental toughness that I didn’t have.” The whole team understood that Walker was preparing for fatherhood at the same time he was adjusting to academia. And that was taking a lot of energy too.

Walker was in Charles Nero’s class that first semester, trying to keep up while processing the bigger life lesson Nero presented: an openly gay Black professor with dreadlocks. “He delivered a sense of comfort in his skin that was new to me,” Walker says. It was a blessing, particularly at that time, “because I was so focused on learning what it meant to be a young Black man in this space.”

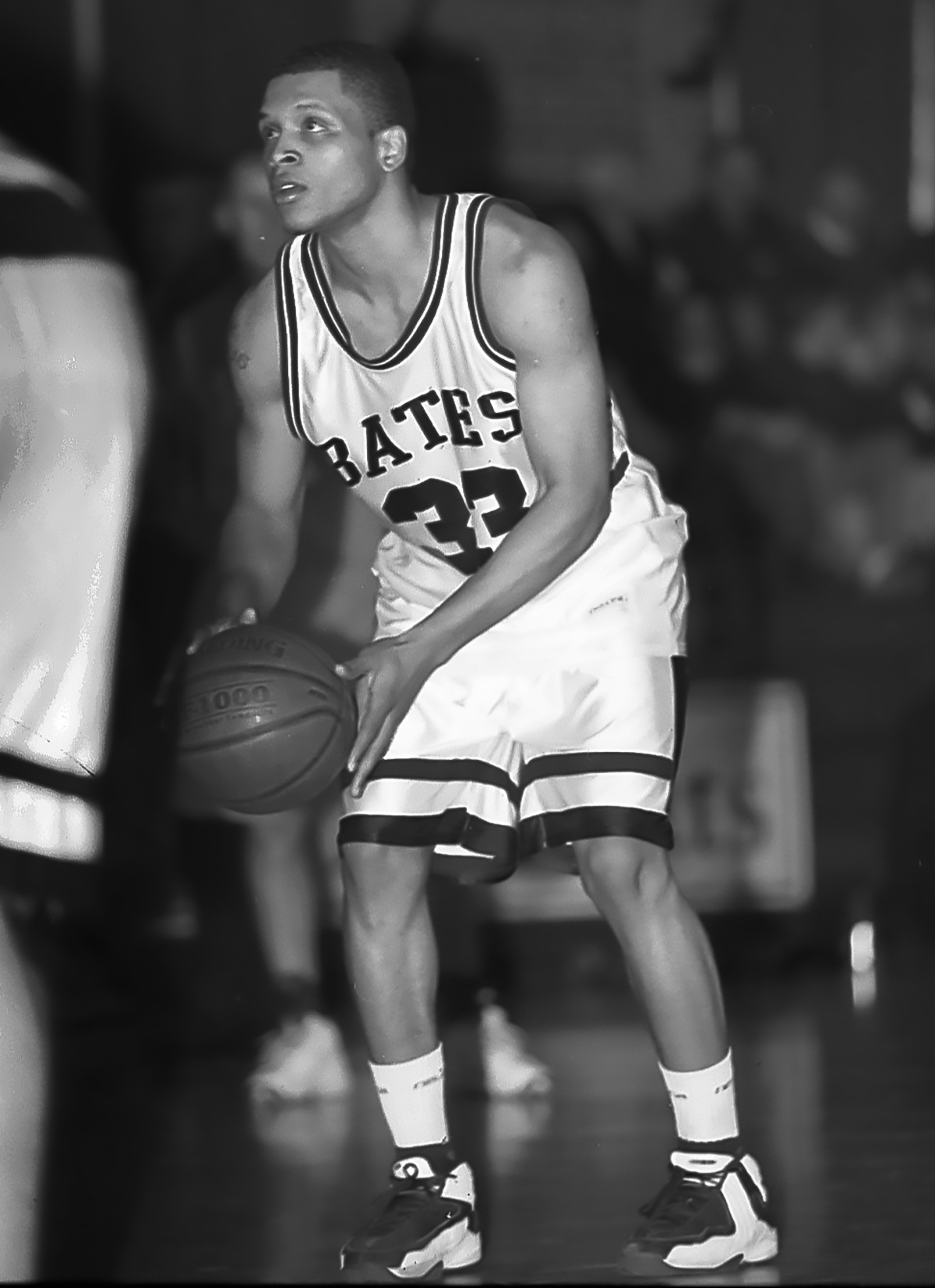

The basketball court was an easy space for him though, and one where he quickly became a leader. The Friday night that Tiauna Walker was being born, Feb. 12, 1999, her dad poured in 17 points in a loss to Williams.

“We’re getting ready to play,” Reilly recalls. “And Ed comes in and goes, ‘Coach, it’s happening tonight.’ And I’m like ‘Ed, we play in an hour.’” Reilly offered to have his wife, Isabel, drive Walker, who didn’t have a license, immediately to Boston. Or they could all leave after the game. Walker chose the latter, wanting to play.

“You can tell I was a young boy back then,” Walker says. “Because you know, I’m a grown man now, and if you said to me, ‘Your child might come within the week,’ I’m canceling my entire calendar.” (Walker is now married and has four children.)

Right after the game, Reilly skipped the postgame speech, Walker skipped the shower, and they both jumped in Reilly’s Honda CR-V, with Isabel, and headed to Boston, arriving about an hour after Tiauna’s birth. “She looked like a little version of me,” Walker recalls.

The Reillys headed back to Lewiston, arranging for Joe’s brother Luke to pick Walker up on a corner near the hospital the next afternoon and drive him back to campus for Bates’ Saturday afternoon game vs. Middlebury.

In his first game as a father, Walker scored a game-high 23 points as Bates defeated Middlebury for the Bobcats’ first conference win of the year. The week his daughter was born, Walker earned NESCAC Rookie of the Week honors.

After the Middlebury game, longtime dean James Reese, heading to Connecticut, offered to drop Walker off in Boston. Himself a former basketball captain at Middlebury, Reese had watched Walker with keen interest, noting the physicality of Walker’s play — standard at Charlestown High, but not typical of NESCAC play.

“Was he smart enough to know how to pull it back?” Reese asks, rhetorically. “Well, yes. He’s the kind of guy who could get two fouls or three fouls in the first half and then never foul again for the rest of the game.” Reese, who was just getting to know Walker, wanted to be present if Walker had things he wanted to talk about. Like a test he was worried about. Or money.

But the drive to Boston was uneventful — until they arrived and Reese said farewell. Walker didn’t get out of the car. Instead, he turned to Reese and said, “You have to come inside. You have to see her.’” Reese was touched, but not sure it was his place. He demurred. Walker insisted. When Reese understood Walker meant it — “Every word of his is intentional” — he parked the car and went up, hoping Walker’s girlfriend didn’t mind meeting another person from Bates. “It was fantastic,” he said.

Over the next three and a half years, Walker created a routine, however unusual the routine was for a Bates student.

Whenever he could, he got on a Greyhound for Boston, and when Starkia could bring the baby up to Bates for a weekend, she would. In between visits, Walker juggled a lot of campus jobs: “Everywhere from the weight room to the gym.” He kept on scoring for the basketball team, amassing 1,409 career points by the end of his senior year, which now ranks him seventh for scoring in Bates men’s basketball history.

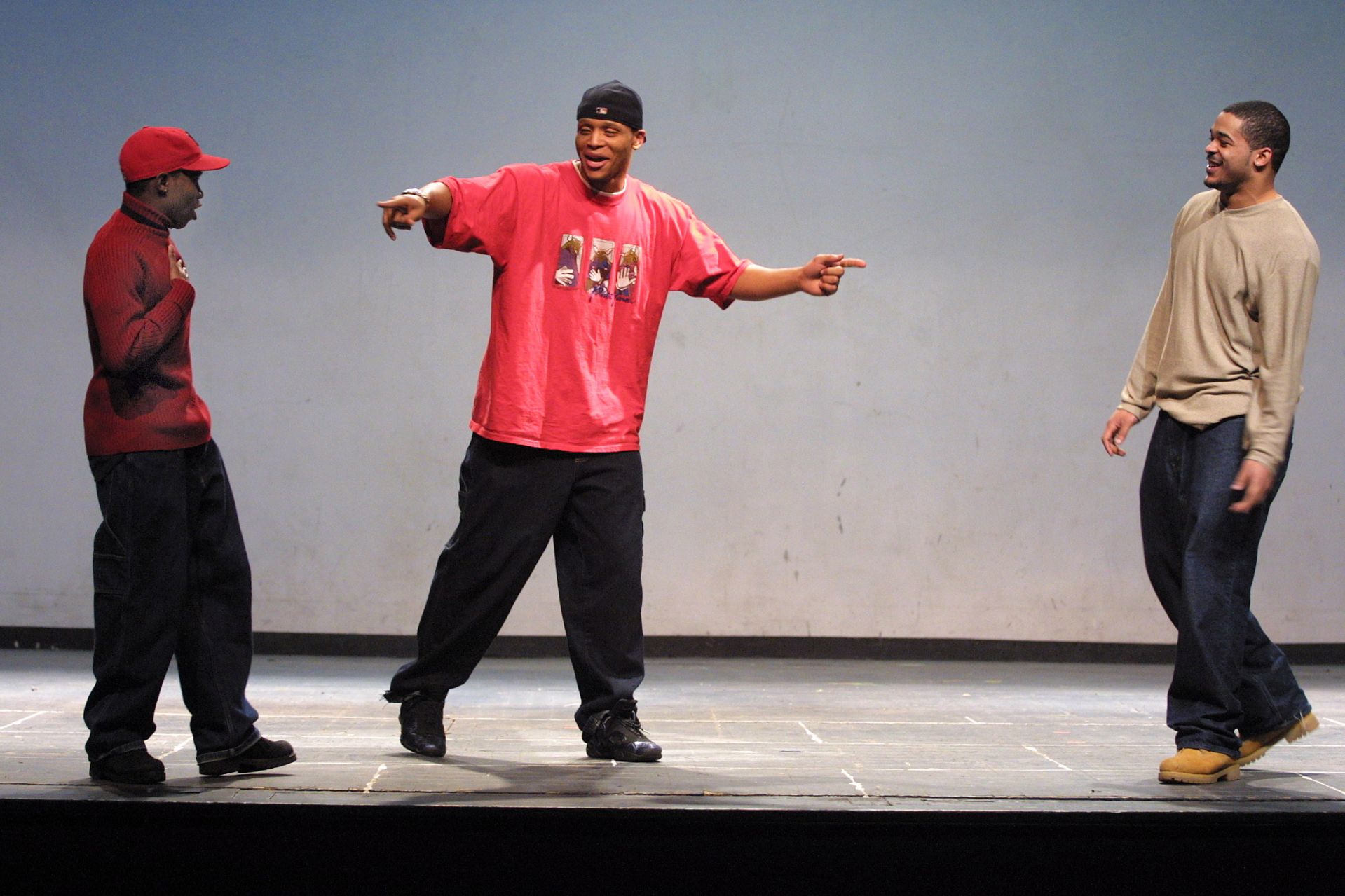

He was a junior advisor. He worked in Admission. He also had a side hustle, performing as a hip hop artist, sometimes as Versatyle — opening for Mos Def in spring 2003 at Bowdoin’s Jack Magee pub — and sometimes as Lyrikal, making a name for himself at Bates.

He “tore it up” at the Ben Mays Center in January 2001, according to The Bates Student, and again that March as Lyrikal, “who has kept heads nodding with his smooth rhymes at shows and parties throughout the year.” When it came time to present his senior thesis in African American studies (now Africana), Walker asked his thesis adviser, Charles Nero, if he could perform it, through music and photography. The concept and execution were “daring and brilliant,” says Nero, the Benjamin E. Mays Distinguished Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies.

Schaeffer Theatre was the venue. “It was overflowing,” recalls Carmita McCoy, then associate dean of admission and director of multicultural recruitment. She remembers sitting in the 10th row, with her son, Nicholas. “Ed was one of his heroes,” she says. “He’s that kind of a guy. He could relate to kids. He could relate to adults.”

Walker could have pursued music as a career. As The Bates Student put it then, go see Ed Walker so “you can say you knew him before he got big.”

But that wasn’t the path Ed Walker chose. After graduation, he worked for nearly four years in admission at Bates, focusing on multicultural recruitment. He made it his business to return to Charlestown High. “Ed is loyal beyond loyal and leads with his generous heart and spirit,” says Dean of Admission and Financial Aid Leigh Weisenburger, who met Walker during her first year at Bates. “He immediately took me under his wing.”

After three years, Walker began looking for work closer to his daughter and took a position at Wheaton College. He went on to get a master’s in education from Cambridge College in Boston and founded Independent Consultants of Education, with the aim to help students like the one he’d been.

Now based in Millbury, Mass., he works as a guidance and school counselor at Cambridge Rindge and Latin School. “Looking back, I’ve always taken jobs to do for young people what I wish someone was able to do for me when I was their age,” he says. That includes sending many young people toward Bates.

He’s been a motivational speaker (when Billy Hart brought him in to speak to a group of middle schoolers at the school where Hart was working, the students were rapt and then rushed Walker at the end. “It was just, like, flocking,” Hart says). He still makes music, faith-based rather than rap. Last year he started a clothing company, R3Raiment, athletic leisurewear that speaks to his spirituality, the three Rs standing for Repent, Reborn and Redeem. Tiauna is one of his models for the clothing line.

While studying abroad in Ghana in early 2020, Tiauna Walker does the famous canopy walk in Kakum National Park. (Photograph by Samuel Mironko ‘21)

For the record, he did not push his first-born, who attended Lincoln-Sudbury High School, into applying to Bates. “Surprisingly, no,” Tiauna Walker says, smiling. “He definitely heavily reps Bates,” she concedes. But they did look at other schools and in the end, Bates was her top choice. “It was all me,” she says.

On campus, she has encountered many who were floored that the baby they knew was now on her own Bates journey, and seemingly in the blink of an eye. Like Charles Nero and his husband, Professor of Hispanic Studies Baltasar Fra-Molinero, who met her and the whole Walker family outside Commons during her first year. “We’re so old now,” Nero quips.

Her major is psychology, with a minor in Africana, so she’s taken a couple of courses from her father’s former mentor. She’s also studied Spanish with Fra-Molinero, who admires her globalist perspective. She has campus jobs as an Admission Fellow and in Post & Print.

There are physical similarities between father and daughter: height, cheeks, smiles. But there was a generational difference Nero observed. Ed arrived with drive but less direction; he was a sponge, soaking up the experience. His daughter arrived “with a very clear idea about her direction.” Junior year, she studied in Ghana. And as she prepares to leave Bates, she says she’s thinking about going into education. “I want to be a principal or a head of school, most likely middle or high school.”

Her favorite class was a developmental psychology course with Rebecca Fraser-Thill, which entailed an immersive community engagement component. Tiauna signed up for visits to D’Youville Pavilion, the elder-care center adjacent to the Bates campus. That’s often a tough assignment to get students interested in, Fraser-Thill says, but “Tiauna was one of the people who was like, ‘Oh yeah, I’m all in.’” “I love infants and elderly people,” Tiauna says. “I like that bluntness that they have.”

In the memory unit, Walker grew close to Joan, a sassy woman who wore earrings and lipstick and was always happy to see Tiauna and tell her stories about her life. For a student, sitting and just listening is a crucial part of the lesson, Fraser-Thill says. “It might sound like someone just rehashing their life, but that’s actually a huge psychosocial journey that a resident is going through.” In those moments, Tiauna was empathetic and thoughtful, Fraser-Thill adds. “She was the only student to reach out and say, ‘I want to write to my resident over the summer.’”

“I’m just grateful for what we have and how far we’ve come,” Ed says.

When James Reese looks at Tiauna, he sees the quiet strength of her father. A similar posture and approach to life. “They both reflect an openness,” Reese says.

Tiauna Walker is leaving Bates with a host of connections to last a lifetime and stretching around the globe. This makes Ed Walker very happy. “Hanging out with her and her friends is like the United Nations. It’s so diverse. Right? She has friends from all walks of life.”

Soon, she will enter a time where it is fine, even natural, for her father to be hands off. (Yes, he proofread her thesis.) To let her fly as he did. “I’m just grateful for what we have and how far we’ve come,” Ed says.

A few years ago, in fall 2017, Tiauna arrived at Bates as a first-year student. As he’s done for so many students, James Reese was there to welcome her.

Reese didn’t want to presume by telling her about meeting her in 1999, when she was a day old, but he wanted her to understand what he remembers: how her father felt so strongly that she was a person who had to be met. “Because that’s really a statement about Ed Walker.”