Welcome to the 25th edition of Good Reads: The Bates College Non-Required Reading List for Leisure Moments.

Begun in 1997 by now-retired Bates College Store director Sarah Emerson Potter ’77 as a gift for graduating seniors, Good Reads features recommendations from current and retired faculty and staff as well as alumni. Alison Keegan, in the Dean of the Faculty’s office, now edits the list.

Potter had long wanted to publish a summer reading list. One day, an encouraging conversation with fellow book lover Ann Harward, the late wife of then-President Don Harward, “gave me a kick in the pants to do it,” says Potter. “She was very supportive.”

Today’s submissions are all electronic, of course. Back in the day, Potter recalls how sociology professor Sawyer Sylvester, one of the earliest Good Reads contributors, would submit his titles with great formality — like a “Letter of Transit” in Casablanca — “on a single sheet of paper, trifold, printed off the computer, and always signed!”

Sylvester is a contributor again this year, as is another founding contributor, Anne Thompson, English professor emerita.

This year, the titles that have two or more recommendations are:

- A Long Petal of the Sea by Isabelle Allende

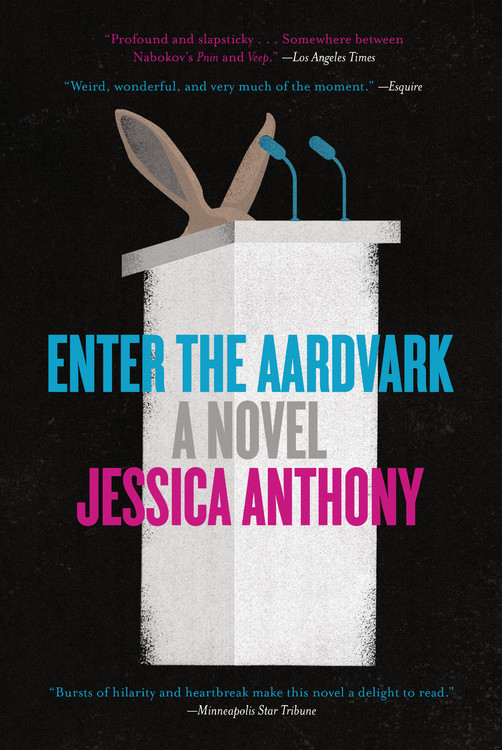

- Enter the Aardvark by Jess Anthony ‘96

- Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler

- The Four Winds by Kristin Hannah

- Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

- The Dutch House by Ann Patchett

- The Overstory by Richard Powers

- Caste by Isabel Wilkerson

Onward!

Áslaug Ásgeirsdóttir, Professor of Politics and Associate Dean of the Faculty

The Eighth Detective by Alex Pavesi. Tells the story of an editor working with an author on an old manuscript. Through conversations about the rules of mysteries, you begin to sense that there is a mystery within the story that slowly unfolds as you read.

Twilight of Democracy by Anne Applebaum. The author has had unique access to the world of conservative politicians in the United States, Britain and Poland. In telling the story of the changes in her conservative circles over the past 20 years, her argument about the twilight of democracy is compelling, even though the book is missing any discussion about the role of conservatives and their policy successes in these changes.

Drive your Plow over the Bones of the Dead by Olga Tokarczuk. Janina lives in a small Polish village where she spends her days translating poetry and taking care of near-by summer homes. Her neighbor turns up dead and soon the mystery deepens. Funny and tragic.

My Life as a Spy by Katherine Verderey. As an American anthropologist doing research in Romania in the 1970s and 1980s, Katherine Verderey was — unbeknownst to her — the subject of secret service surveillance until the collapse of communism in the late 1980s. Much later she gets access to her more than 2000-page file and begins to reflect on it and what it means to be surveilled.

Outline Trilogy (Outline, Transit, and Kudos) by Rachel Cusk. This trilogy tells the story of a female writer and her encounters with friends and strangers. The books simultaneously tell you enough of her encounters, but also leave you wanting more.

Split Tooth by Tanya Tagaq. A work of auto-fiction about a girl growing up in Nunavut mixes fact, fiction and myth. It is often hard to tell which is which. Filled with joy and heartbreak, where the last chapter still haunts me.

Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men by Caroline Criado Perez looks at how various public policies (for example in education, health care, urban design) are suboptimal as they fail to account for gender. The book is well written with great examples.

Pamela Baker ’69, Helen A. Papaioanou Professor Emerita of Biological Sciences

One of the best books I read this year is Lisa Genova‘s new book Remember: The Science of Memory and the Art of Forgetting. It is her first non-fiction book and covers so much up to date information about neuroscience (her Ph.D. after all), yet still in her very readable, personable style. It is truly a work of science and art.

Another good one is This Magnificent Dappled Sea by David Brio. It covers a lot of the biology of transplantation, and finding the match for a present-day child with a blood disease reveals truths of Italy in World War II.

Completely different and very funny is a retelling of Pride and Prejudice in current America: Eligible by Curtis Sittenfeld.

Jonathan Cavallero, Associate Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies

Born a Crime by Trevor Noah has been listed by a number of others over the years. I don’t have much to add to what has already been said. It’s a great book and well worth the time.

Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination by Neal Gabler. It is difficult to fully capture the significance of Walt Disney to American cinema and animation generally, but Gabler does it. From animation techniques to the structure of labor in Hollywood studios and all points in between this book is an eye-opening history of the studio chieftain as well as the institution itself.

American Spy by Lauren Wilkinson. Some of the most interesting work in recent years focuses on characters from marginalized groups that work within and for institutions that marginalize them. Chinonye Chukwu’s film Clemency took on the issue and so does Wilkinson’s novel. Both are wonderful.

Jane Costlow, Clark A. Griffith Professor Emerita of Environmental Studies

An Unnecessary Woman by Rabih Alameddine. Amazing narrative about a woman in Beirut who defies all sorts of expectations. I loved the book for her, most of all — but also for its evocation of the city, in both war and peace. She’s a translator, and one of the pleasures of the book for me was settling into a world in which identity (both hers and the reader’s) expands across language, gender, era…

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin. I’d never read this. Along with Robyn Davidson’s Tracks I spent several weeks imaginatively trekking through the Australian outback. I did in fact learn a lot from these authors about Australian aboriginals (and Australians’ treatments of them), but both books are as much about the authors themselves as about the places and people they encounter.

The Empire Trilogy: Troubles, The Siege of Krishnapur, and The Singapore Grip by J.G. Farrell. Farrell is brilliant and ruthless at skewering the stupidities and racism of British colonialists. Not just “colonialism” but individual participants in the system. Brilliant social satire, The Singapore Grip is Monty Python plus Tolstoy.

A Terrible Country by Keith Gessen. Young Russian-American goes to Moscow to live with his grandmother, who is very elderly and starting to get a bit confused (but still regularly beats him at anagrams). This is Gessen’s portrait of Moscow in the early 2000s; the relationship between the hero and his grandmother is beautifully described.

The Hiawatha by David Treuer. I am currently reading my way through anything and everything Treuer has written (now working on Rez Life, non-fiction/memoir about contemporary Indian lives). The Hiawatha is the story of several generations of an Ojibwe family resettled in Minneapolis: along with the heart-breaking story of a family that is not really surviving various acts of violence, the novel has descriptions of men at work — felling trees in the northern Minnesota forests, building the skyscrapers in downtown Minneapolis, fishing in a northern river — that are just amazing.

Grace Coulombe, Director of Math and Statistics Workshop and Lecturer in Quantitative Studies

Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony ’96 and Project Hail Mary by Andy Weir

Deborah Cutten, Academic Administrative Assistant

I think I’ve read more novels this year than in any other. Looking back on this list I note they were all thrillers and dark conspiracy stories that spoke to my own spirit during the pandemic. You would think I would have searched for uplifting and optimistic stories to cheer myself, but perhaps, real life didn’t look so bleak in comparison.

- Ice Hunt, Amazonia, and The Demon Crown: A Sigma Force Novel all by James Rollins

- The Blood Gospel: The Order of the Sanguines series by James Rollins and Rebecca Cantrell

- The Sancti Trilogy (The Sanctus, The Key, and The Tower) by Simon Toyne

- The Templar novels (The Last Templar, The Templar Salvation, and The Devil’s Elixir) by Raymond Khoury

- The Trench by Steve Alten

- And last but certainly not least, Enter the Aardvark by Jessica Anthony ’96

Karen Daigler, Director of Graduate and Professional School Advising, Center for Purposeful Work

The Art of Inheriting Secrets by Barbara O’Neal. When Olivia Shaw’s mother dies, the sophisticated food editor is astonished to learn she’s inherited a centuries-old English estate — and a title to go with it. Raw with grief and reeling from the knowledge that her reserved mother hid something so momentous, Olivia leaves San Francisco and crosses the pond to unravel the mystery of a lifetime.

The Lost Girls of Devon by Barbara O’Neal. The Lost Girls of Devon follows the story of Zoe, her estranged mother Poppy, her grandmother Lilian and her daughter Isabel. When Zoe’s childhood best friend Diana goes missing, she and her daughter Isabel head to Devon from Santa Fe to try and find her.

Beneath Scarlet Sky by Mark Sullivan. This is about an Italian teenager’s courage and resilience during one of history’s darkest hours. He helps Jews escape over the Alps in an underground railroad. Not my usual, but I really enjoyed it.

This is How it Always Is by Laurie Frankel. This book is about parents forging uncharted waters in order to help their transgender children live happy, healthy lives in a society that still largely defines gender by what’s in your pants. Laurie Frankel takes those real-life experiences and puts them into a big-hearted story of family and secrets. Loved this book.

The Downstairs Girl by Stacey Lee. The Downstairs Girl is a powerful portrait of one plucky Chinese-American heroine living and working in the beginning of the Jim Crow south. She works by day as a maid for a wealthy socialite family while at night she writes an advice column for Southern women. She uses that platform to shed light on gender and racial discrimination. THAT does not always go over well.

28 Summers by Elin Hilderbrand. A decades-long, once-a-year, secret love affair.

The Way of Beauty by Camille Di Maio. The Way of Beauty is a charming, sweet and heartwarming historical women’s fiction novel that touches on many topics while bringing a piece of history to life here with Penn Station and blending the lives of two very strong women and the people connected to them. Loved the interesting compelling characters and reading about the women’s suffrage movement.

Carol Dilley, Professor of Dance

I am thoroughly enjoying The Final Revival of Opal and Nev by Dawnie Walton. The structure, the prose, the characters and the story just keep unfolding throughout.

For those who read in Spanish, Patria by Fernando Aramburu is an utterly gripping story of the intimacy of violence in the Basque region of Spain. They made an excellent TV miniseries as well.

Phil Dostie, Assistant in Instruction

The Story of Earth by Robert Hanzen. Brief, approachable, interesting and engaging this book covers our planet’s geological history from stardust to present.

Plant Propagation Principles and Practices by Hartmann and Kester. Its current ninth edition is rather expensive but older, used editions are available shipped to your door for less than $5.00. While it’s sometimes dry, it’s always informative. I find myself using it every spring as a reference for grafting or looking the best way to propagate my lilacs and forsythia.

Northeast Foraging by Leda Meredith. Full of pictures and information on where, when, and how to harvest some of the edible wild plants around you, this book is one of the best foraging references for our state.

The Parable series by Octavia Butler. The Parable of the Sower and The Parable of the Talents (Trigger waring depictions of rape, torture, and other forms of violence are written in these book). Published in 1993 and 1998 respectively, and set in the mid-2020s. These are the first two books in what was supposed to be a trilogy, unfortunately the author died before completing the works and getting to the end of the second is very much like having a captivating conversation with a friend suddenly cut short. They leave you wanting more and knowing you’ll never get it.

The level of insight and forethought that the author had for the writing of these two books allows her to paint a future that is a portrait of modern-day America with a twisted black shadow looming over it. Additionally, there are some pretty terrifying parallels in this storyline with our current politicians/political systems and, while I’m aware that the phrase did not originate with the 2016 candidate for president, I could feel myself blanching when reading certain lines from the book. If I didn’t already know that the man struggled with basic sentences I would have sworn he read Butler first in order to coopt her work. They’re well written, fast reads that captivate and terrify. They’re the written equivalent of driving by the after effects of a particularly violent car crash; you want to look away and yet you can’t. These two books are worth the read.

White Fragility by Robin Deangelo. Deangelo takes the difficult topics of race and accountability and presents them in an approachable manner.

How to be an Anti-Racist by Ibram X Kendi. The author explores the structural underpinnings of racism and helps the reader to find tools to recognize and address racist laws, behaviors, and societal norms, a good start into the subject.

Elizabeth Durand ’76

Invisible Girl by Lisa Jewell. A mystery full of twists and turns and changing points of view; keeps you off balance right up to the end.

Anxious People by Fredrik Backman. A book about idiots, love, ineptitude, and optimism. My favorite read of 2021.

Transcription by Kate Atkinson. Another one set in World War II, behind the scenes, so many times I get to the end of the book and the ending is all wrong. This is not one of those books.

The Glass Hotel by Emily St. John Mandel. I finished it and immediately had to read it again.

The Rose Code by Kate Quinn. More World War II. Young women from vastly different backgrounds end up at Bletchley Park working as code breakers. If Kate Quinn is the author, the book will end up on my “best” list.

Angela’s Ashes by Frank McCourt. I missed reading this one when it was a bestseller (and won the Pulitzer Prize) in the late 1990s. Utterly absorbing and appalling.

Band of Sisters by Lauren Willig. A naive group of Smith graduates head for France in 1917, while World War I is still very much in progress, to do good works among the civilians. Reality is much grimmer than they anticipated. Based on a true story and beautifully written.

Francis Eanes, Visiting Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies

- A Planet to Win: Why We Need a Green New Deal by Kate Aronoff

- Capital City: Gentrification & The Real Estate State by Samuel Stein

- The Geography of Risk: Epic Storms, Rushing Seas, and the Cost of America’s Coast by Gilbert Gaul

- Freedom Farmers: Agricultural Resistance and the Black Freedom Movement by Monica White

Melinda Emerson, retired colleague

The Wild Inside, Mortal Fall, The Weight of Night & Sharp Solitude by Christine Carbo. Novels set in and around Glacier National Park. If you like Paul Doiron’s books, you will enjoy these.

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes by Suzanne Collins. The prequel to the Hunger Games Trilogy. It starts as 18-year-old Coriolanus Snow is preparing for his one shot at glory as a mentor in the Games.

Virgin River series by Robyn Carr. Much better than the Netflix series, based on the books.

Mrs. Sherlock Holmes by Brad Ricca. The first-ever narrative biography of this singular woman the press nicknamed after fiction’s greatest detective. Her poignant story reveals important clues about missing girls, the media, and the real truth of crime stories.

The Haunting of Brynn Wilder by Wendy Webb. This novel is partially a paranormal romance, partially a mystery, partially a woman trying to regroup after taking time off from being a professor of English lit to reset.

Under a Gilded Moon by Joy Jordan-Lake. This is historical fiction that features characters who actually lived and became a well-known part of American history. The time is the late 1800s and young George Washington Vanderbilt II has built Biltmore House in the Appalachian Mountains.

Time is A River by Mary Alice Munroe. This is an insightful novel that will sweep readers away to the seductive southern landscape. Recovering from breast cancer and reeling from her husband’s infidelity, Mia Landan flees her Charleston home to heal in the mountains near Asheville, N.C., where she seeks refuge in a neglected fish cabin owned by a fly-fishing instructor, Belle Carson.

Wesley the Owl: The remarkable Love story of An Owl and His Girl by Stacey O’Brien chronicles the author’s rescue of an abandoned barn owlet, from her efforts to resuscitate and raise the young owl after an injury that prevented it from returning to the wild through their nineteen years together, during which the author made key discoveries about owl behavior.

Above the Bay of Angels by Rhys Bowen. A single twist of fate puts a servant girl to work in Queen Victoria’s royal kitchen, setting off a suspenseful, historical mystery.

West with Giraffes by Lynda Rutledge. An emotional, rousing novel inspired by the incredible true story of two giraffes who made headlines and won the hearts of Depression-era America.

Nathan Faries, Assistant Professor of Asian Studies

John le Carré passed away late in 2020. All of his spy novels about British Intelligence are amazing — reportedly required reading for Soviet KGB recruits in the 1970s and ’80s. I would start with the George Smiley novels, and if you want to “cheat” and jump into the BBC adaptations (with Sir Alec Guinness as Smiley) —Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy and Smiley’s People— who would blame you? (Or watch Michelle Pfeiffer (sigh) and Sean Connery in The Russia House: “You are my country now.”) The books are more complete, naturally, but these filmed adaptations still capture the anti-jingoistic moral ambiguity of spy craft during the Cold War as le Carré envisioned it.

David Sedaris occasionally gets a little too sad for my moods to bear, but his essays are mostly hilarious and addictive. I recently re-read When You Are Engulfed in Flames and Dress Your Family in Corduroy and Denim. Check out his “Nuit of the Living Dead” or his perennial NPR reading of “Santaland Diaries” about his experience working as a Macy’s elf. The audiobooks are read by Sedaris himself, and his voice and cadence are part of the experience.

Max Brooks, Devolution: A Firsthand Account of the Rainier Sasquatch Massacre. As a big fan of Brooks’ World War Z (not the movie), I was compelled to read this “found-footage/fake-documentary” follow-up. In World War Z, Brooks is able to play with multiple genres and produce what is essentially a complex short-story anthology. Devolution is more linear and focused, but it is still a fun and compelling page-turner with all the X-Files–style pseudo-science in the background and a playful plot twist for a coda.

Dan Girling, Mail and Materials Handling Clerk, Post & Print

The Stand by Stephen King. In a year derailed by COVID, I found it a fitting time to read this classic from Stephen King. The story begins with a deadly form of influenza sweeping the world, but in the aftermath, the few survivors find themselves in a struggle between good and evil. While the Stand is in no way a guide on how to survive a pandemic, it does offer a thrilling story that will captivate you from beginning to end.

If It Bleeds by Stephen King. This is a collection of four stories. While I usually read Stephen King’s longer works, the variety here was a nice change of pace. The highlight for me was the story “The Life of Chuck” which retells the life of a man in three separate, uniquely designed sections.

The Water Dancer by Ta-Nehisi Coates. Blending historical fiction with elements of fantasy, this novel takes place in 19th-century America, where a young man discovers he has teleportation abilities that allow him to free himself — and later others — from the bonds of slavery. The Water Dancer covers a bleak period in history, but the novel’s imaginative style and premise make it a story worth reading.

A Beautifully Foolish Endeavor by Hank Green. This book concludes the story that began with Hank Green’s first book, An Absolutely Remarkable Thing. After a mysterious being known only as Carl appears on Earth, the world questions whether they can trust it and what motivations Carl might have. I appreciate how these novels take an old science fiction idea and use it to explore modern concerns, such as our reliance on technology, misinformation on social media, and the influence of big corporations.

Phyllis Graber Jensen, Director of Photography and Video, Bates Communications Office

Coming of Age in Mississippi by Anne Moody and The Resisters by Gish Jen. The hellish past and dystopian future: how two strong women struggle and prevail against their circumstances.

Meg Gresh, Assistant to the Dean of Faculty

- Verity by Colleen Hoover

Bruce Hall, Network Administrator, Information and Library Services

I used some of my pandemic reading to catch up on the history of the US founding. Based on that, I recommend 1787: The Grand Convention by Clinton Rossiter. The title is the first thing I learned: We call it the “Constitutional Convention,” they didn’t. The times were fluid and the result not pre-determined. Rossiter sets the scene with great detail, including the political situation that led to the meeting in Philadelphia. He includes biographies of all of the participants, even the minor ones. They and their world come alive as he puts them in context. He describes the economic interests and setting of each state. This includes the population divisions between free and slave within each state.

It is only after more than a third of the book, that you get to Philadelphia for the Grand Convention itself. About the middle third of the book is Rossiter’s account of the day by day debates. These make for compelling reading and are relevant to many issues we contend with today. The final third of the book covers not only the struggle for ratification but the early years of setting up the new government under the Constitution.

Indeed, some of my favorite parts were in his concluding chapter where Rossiter goes through important items that ‘completed’ the Constitution. For example, he ends in 1803 with Chief Justice John Marshall establishing the doctrine of judicial review in Marbury v. Madison. It is at this point that Rossiter says “…the Grand Convention stood at last adjourned.” Even that suggests that there is much more to study in later US history as the people of the United States through amendments, laws, and practices seek to “form a more perfect Union” and “establish Justice”.

Rossiter includes a detailed appendix of documents so that you can trace the development of the Constitution through multiple plans and proposals. You can even see the deficiencies of the Articles of Confederation that the Constitution was meant to correct. Curiously, Rossiter does not include “The Declaration of Independence” in his appendix of documents. You can remedy that by reading the Bates Common Read book of a few years ago: Our Declaration by Danielle Allen.

I have read 72 of the 85 Federalist Papers written in 1787 and 1788 by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay in support of the ratification of the Constitution in New York. Considering that they were written as part of a public political debate, they are remarkably frank. Madison observes in No. 51 that “ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Hamilton warns in No. 6 that people are “ambitious, vindictive, and rapacious”. I’m sure they would be ready to survey our politics now as well. Balancing this somewhat bleak, if clear-eyed, view, Madison in No. 55 also says that there is “sufficient virtue…for self-government”. While some things under the Constitution did not turn out the way they expected or desired, their incisive study also bears directly on many of the issues of today.

Joe Hall, Associate Professor of History

The Overstory by Richard Powers. It’s not my favorite novel, but I loved what Powers did with shifting the focus away from people to also include trees. I learned a lot about trees (Powers did some great homework), but I also appreciated the ways that he showed us how people are connected to trees in ways that we, with our shorter, faster lives, often fail to recognize.

Considering that Maine is the country’s most forested state, one could do worse than to think in new ways about our numerous neighbors.

Tyler Harper, Program in Environmental Studies

The Bear by Andrew Krivak. An elegantly-written and poignant novel about the Earth getting along just fine without us.

Tender is the Flesh by Agustina Bazterrica. A brutal but thought-provoking satire about the moral and environmental perils of factory farming.

Bill Hiss ’66, retired colleague

Improbable Voices: The History of the World Since 1450 Seen from 26 Unusual Perspectives by Derek Anderson ’85. Derek is a Bates alum and history teacher at a high school in California. His 700-page book is a marvel, written over 8 years, and scrupulously footnoted. Playfully, he follows the logic of the alphabet to explain world history, choosing 26 individuals from a Portuguese explorer in the 1400s to a still-living woman environmental scientist.

His 26 portraits are of people who were not historically famous but achieved something that shaped modern history. His “Exhibit A,” for example, a Portuguese explorer named Albuquerque, figured out how to use adjustable triangular sails to sail against the wind, and thus explore the southern coast of Africa and then around to India, where he was later a governor for Portugal, establishing the patterns of European colonial empires.

Crisis in the Red Zone: The Story of the Deadliest Ebola Outbreak in History, and of the Outbreaks to Come by Richard Preston. Ebola only a hint of the future, as the title suggests.

Empty Mansions by Bill Dedman and Paul Clark Newell Jr. Huguette Clark was an heiress who, though not ill, spent her last 20 years in a hospital room in New York, triggering a monumental lawsuit over her $300 million estate. Her family was a classic American story of immense riches put to bizarre uses.

Sixty Miles from Contentment: Traveling the 19th Century American Interior by M.H. Dunlop. Many foreigners wanted to see the American frontier and went to great trouble and some danger to get there. There were also some wonderful cultural clashes: upscale British visitors expected to hire servants, but no American was willing to work as a servant, even while taking on frightful labor for other ends.

The Pioneers by David McCullough. McCullough is one of our fine story- teller historians, and this book no exception: the settling of Ohio when it was utter wilderness to arriving whites.

Liberty Men and Great Proprietors: The Revolutionary Settlement on the Maine Frontier, 1760-1820 by Alan Taylor. In some ways, a parallel book for Maine to The Pioneers and Sixty Miles from Contentment. In the years surrounding the American Revolution, largely poor settlers, often Revolutionary War veterans promised land for their service, came to Maine for what they expected to be free land, if they settled and improved it. But the “Great Proprietors”, including a fellow named Bowdoin, had immense land grants from the King, and wanted these settlers to buy the land. Sixty years of threats and intimidation from both sides.

The Storm on Our Shores: One Island, Two Soldiers and the Forgotten Battle of World War II by Mark Obmascik. Few places are less habitable than the Aleutians. When one of the most distant islands was invaded by the Japanese, the American military decided they needed to retake it. The book is the account of a Japanese but American-trained physician who got drafted into the Japanese medical corps while home to get married and see his parents, and then sent on this invasion. He was killed by an American soldier who found and kept his touching diary, and decades later tracked down his descendants to return it.

In Search of England by H.V. Morton. Morton was an early British travel writer who wrote a number of books about different parts of Britain. His books sold well: this one, published in 1927, saw 11 printings in five years. He was a charming and elegant writer, entranced by medieval cathedrals and villages, and regarding almost everything else that happened in Britain after the invention of the steam engine as regrettable. Like his In Search of Scotland, fascinating to read about places we may know from a century later.

A Gentleman in Moscow by Amor Towles. A minor Russian nobleman is sentenced by a Revolutionary court to spend the rest of his life in an elegant hotel in Moscow. Wonderfully told novel, with a riveting collection of oddballs and survivors flowing into the hotel.

The Shipping News by Annie Proulx. Fiction masterpiece.

Emily Kane, Professor of Sociology

Here are some things I read this year that have particularly stuck with me for various reasons:

- Parable of the Sower and Parable of the Talents by Octavia Butler

- Apeirogon by Colum McCann

- You Can’t Stop the Revolution: Community Disorder and Social Ties in Post-Ferguson America by Andrea Boyles

Alison Keegan, Administrative Assistant and Supervisor of Academic Administrative Services, Office of the Dean of the Faculty

The Book of Longings by Sue Monk Kidd. Imagine Jesus had a wife and her name was Ana. She’s rebellious, independent, and brilliant, bent on defying the expectations placed on women. This gorgeous, imaginative, and creative reimagining of what we know of Jesus, but through the eyes of Ana, is a stunning reflection of women’s longing, silencing, and awakening, and was the first of two best books I read in 2020-2021.

The Invisible Life of Addie LaRue by V.E. Schwab. Few books touch me and are unforgettable in the ways that this book did and is. To say that I didn’t want this to end is an understatement and I found it difficult to imagine reading anything in the future that is as beautiful and striking storytelling as this book. This is a book about a girl, a boy, a devil, and the stories that get told, repeated, and remembered. This is a tale of power dynamics and imbalances and what humans are willing to do to not feel trapped and alone.

This is all about a young girl who lives her life for herself, who lives her life in spite of the odds, who lives her life in hopes someone will recall her from memory. The second-best book I read in 2020–21.

Where the Forest Meets the Stars by Glendy Vanderah. Magical, whimsical, debut novel. I was charmed by this story of two neighbors, each dealing with their past and its effects, and a young girl claiming to be an alien, who brings them together in her quest for 5 miracles. Without giving anything else away, simply put, this is a beautiful story of friendship, family, and recovering from past wounds to move forward to present healing.

The Sun Down Motel by Simone St. James. I couldn’t read this book at night because the creep factor was way too high…then I couldn’t put it down in the daylight. Perfect summer twisty dark pleasure.

The Four Winds by Kristin Hannah. Kristin Hannah does it again. She has this incredible talent for making the landscapes of her novels every bit as much a character as the people within. In this case, it’s Texas, 1934 during the Dust Bowl/Great Depression era. This is a book about a woman’s choice to fight for the land she loves or go west in search of a better life. I found myself nearly choking on the descriptions of the dust storms, and the suffocating feeling of the gritty, grainy sand at every turn of page. Not an uplifting book by any means, but a beautiful, real novel of courage and the indomitable spirit we are capable of when all other hope is lost.

John Kelsey, Professor Emeritus of Psychology

I just finished reading The Code Breaker by Walter Isaacson about Jennifer Doudna (our graduation speaker when we last had such things) and the research on CRISPR that led to her Nobel Prize in 2019. Isaacson does an excellent job of explaining the relevant biology at a lay level and revealing the personalities behind the intense West Coast/East Coast competition to discover how this gene-splicing technique (CRISPR), evolved by bacteria over millions of years, can be used to treat human disease, including COVID-19. An absolutely fascinating detective story.

I immensely enjoyed The Mirror and the Light which completed the trilogy by Hilary Mantel about Thomas Cromwell (Henry VIII’s advisor and shaker). Wolf Hall, the first of the trilogy, remains my favorite book of the last several years, and although the latest is longer with some unnecessary digressions, it is also lovely and a marvelous comment on class, religion, and power in pre-Elizabethan England. Her writing is just a joy for me to read.

Although I have not been a big fan of Tana French, I enjoyed her recent The Searcher: A Novel about an American who recently immigrated to rural Ireland to find a new life. In contrast to her other books, this one focuses more on character development and culture than on a mystery (although there is, of course, a mysterious disappearance). I could easily imagine having a beer with the protagonists.

Grace Kendall, Director of Design Services, Bates Communications

Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power by Pekka Hämäläinen. Billed as a more complete history of the Lakota nation, this book sets out to share a history in which the Lakota, and the “seven council fires” — distinct bands within the nation — are less victims of an all- consuming colonizing power and more a powerhouse making purposeful and measured political decisions. It delves into how the Sioux shaped the political landscape in their region(s) both before and after the arrival of white colonizing forces, and it includes a lot of info about inter-nation relations between the Sioux and other indigenous nations as well as between the Sioux and the British, French, and (later) Americans.

It is a very dense read, and there are aspects of it that are still confusing. (I don’t think Hämäläinen does a great job explaining Sioux vs. Lakota / Nakota / Dakota, for example, and how the seven bands fit within that structure.) But it’s the most complete history of an indigenous nation that I’ve read. Even still, folks will notice that it’s very male-centric. That may be because the documents available for research, often having been curated by men, focused on other men, but it’s not something that Hämäläinen addresses, so that’s worth noting and being aware of as you go in.

A Certain Hunger by Chelsea G. Summers. There’s no way around it, so let’s start by saying this novel is about cannibalism. The story is fabulously written, and Summers does a really great job expressing the joy that food critic Dorothy Daniels gets from her work — both official and “off the books.” Although it’s an odd road to get there, the book is about a woman deciding, reluctantly at times, that she’s better than the men around her, and her journey to embrace that. Its satirical view of foodie culture is super entertaining to read, and although the main character is a psychopath…she’s an entertaining one. The subject matter may be dark, but this story was ultimately one of the funnest reads of 2020 for me. Whether that says more about me or 2020, I do not know.

The Only Good Indians by Stephen Graham Jones. This book was my first introduction to writer Stephen Graham Jones, and I’m so glad to have a new favorite author to add to the mix! It’s a sort of sci-fi/horror story that follows four Blackfeet men as they grow up and are forced to come to terms with an event in their past that has unleashed a supernatural entity bent on revenge.

The Mercies by Kiran Millwood Hargrave. I previously had never learned about the witch trials in northeastern Norway in the early 17th century. The Mercies is a novelization of one such rash of trials, taking place in the village of Vardø. I loved the book for its following of female stories, especially its focus on a village-wide tragedy that required women to step up in new ways in order to ensure the village’s survival. When some didn’t want to step back into their former roles, they were the target of derision and labeled as witches. The Mercies is an interesting story following women who chafe at their traditional roles and the kinds of fallout that results, which is something that still resonates, 400 years later.

Sharks in the Time of Saviors by Kawai Strong Washburn. This is a really interesting story about the pressure that comes with greatness. Main character Nainoa is marked for supernatural things at the age of seven when, having fallen from a boat, he is delivered safely to his mother’s arms in the jaws of a shark. As he grows up and develops unexplained abilities, it’s clear to his family he’s been blessed by the gods. With the pressure to use his abilities to help his family escape poverty, and the wedge it drives between him and his siblings, what could be a larger-than-life sci-fi story ends up a personal tale about family, heritage, and responsibility. Beautifully done.

Cheryl Lacey, Director of Dining Services

- Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell

- The Lonely City by Olivia Laing

- The New Jim Crow by Michelle Alexander The Murmur of Bees by Sofia Segovia Afterlife by Julia Alvarez

- The Vanishing Half by Brit Bennett White Rage by Carol Anderson

- Sigh, Gone by Phuc Tran

- Shakespeare in A Divided America by James Shapiro

Peter Lasagna, Head Men’s Lacrosse Coach

I would like to submit Parable of the Sower by Octavia Butler for this summer’s Good Read’s list. Recommended by our son and an author I have enjoyed before, I found this book to be one of the most masterfully crafted and compelling (at times terrifying) of my entire reading life. Images remain that will remain forever. It also describes a place, and life that is not hard to imagine existing right around the corner….

Daniel Lindahl, Senior Database and Oracle Application Server Administrator, Information and Library Services

This year, I read Isabel Wilkerson’s Caste: The Origins of Our Discontents and I couldn’t not share. I’d imagine you’ll get multiple notes on this. Wilkerson, who is a Bates honorary degree recipient and former Commencement speaker, is a remarkable writer. In Caste, she unfolds the framework of inequity at the heart of the history of our nation and enumerates the core pillars of the social contract that allows and enforces it.

Her explication of a structure that codifies and in fact depends upon a strict system of caste, largely parallel to the caste system of India, is clear and personal in a balance of clinical examination and very personal, very real accounts of the lives it has forged. So powerful was my connection to the work that I found understanding of pieces of my own childhood, of my own life, that I only now realize that I had never understood, or had understood in an entirely different context.

Kathy Low, Professor of Psychology

- Stormy Weather by Paulette Jiles

- Yellow House by Sarah Broom

- Deacon King Kong by James McBride

- A Gentleman’s Murder by Christopher Huang

- Night Boat to Tangier by Kevin Barry

- Snow by John Banville

- Sweetland by Michael Crummey

- The City We Became by NK Jemison

- Drive Your Own Plow Over the Bones by Olga Tokarczuk

- Florida by Lauren Groff

- Why Fish Don’t Exist by Lulu Miller

- The Friend by Sigrid Nunez

- Washington Black by Esi Edugyan

- The Night Watchman by Louise Erdrich

- The Mirror and the Light by Hilary Mantel

- The Dutch House by Ann Patchett

- The Dazzle of Day by Molly Gloss

Judy Marden ’66, retired colleague

Last year’s Good Reads showed that Richard Powers‘ The Overstory was widely read by the extended Bates Community. Re-reading it led me to also re-read Annie Proulx’s Barkskins, and find new significance in this comprehensive history of the development of the logging industry in the US and its influence on settlement by Europeans, effect on indigenous peoples in the Americas and New Zealand, and predictions for the future of humanoids. Highly recommended as we contemplate the future, with its relentless extinctions.

Spring bird migrants are here, and nesting has begun. Three great reference books to peruse in addition to the regular field guides and apps are Sibley’s What it’s Like to be a Bird (if they make it to their first breeding season, songbirds in general have about a 50 percent chance of surviving each year), Julie Zickefoose’s Baby Birds, an Artist Looks in the Nest, and Peter Vickery‘s Birds of Maine, edited by our own Barbara St. John Vickery ’83.

Migrations, a novel by Charlotte McConaghy. A haunting futuristic story of a woman who tracks the rapidly disappearing ArcticTerns from the Arctic to the Antarctic. I simply had to read it, since my friend Andrew Stowe ’06 did exactly that with his Watson Fellowship after he graduated.

The Library Book by Susan Orlean. The story of the devastating fire at the Los Angeles Central Library — and much more. Did you know that the temperature at which book paper catches fire and burns is 451 degrees Fahrenheit — and that is why Ray Bradbury’s book from 1951, Fahrenheit 451, has that title? I’m reading that classic now, for the first time…it is especially relevant in these days of history erasure and culture-canceling.

Tom McGuinness, Director of Institutional Research, Analysis, and Planning

I didn’t read any books that I truly loved during the past year, but I’ll highlight a couple that I really enjoyed. The first is Mediocre: The Dangerous Legacy of White Male America by Ijeoma Oluo, whose voice I really enjoy. It includes an excellent chapter on higher education, in which she explores her conflicted feelings about appreciating higher education as a pathway to a better life but also recognizing its embedded racism. The second is The Guest List by Lucy Foley. This novel is an engaging (though somewhat ridiculous) whodunit set at a wedding on a remote island off the coast of Ireland.

Meghan Metzger ’07, former colleague

If Women Rose Rooted: A Life-changing Journey to Authenticity and Belonging by Sharon Blackie. A spectacular book that has impacted my own path and growth in profound ways.

Kevin Michaud, Campus Safety Officer

I would like to recommend the following book which I could not put down once I started to read it: North River Depot, A Novel about the United States First Operational Nuclear Weapons Storage Site by John C. Garbinski.

I love the novel approach to telling this story which is based entirely on facts involving the establishment of this site in Caribou, Maine on land which the United States Government had purchased in part from my Grandparents in 1950.

This book details the history of one installation in particular and its historical contribution to the nation’s security. These distinctive contributions remained a TOP Secret for more than 40 years. This is a story of loyalty, integrity and pride. What these men did, what they had to do, and why their story has never been told until now, is the theme of this book.

Christine Murray, Social Science Librarian

- Owls of the Eastern Ice: A Quest to Find and Save the World’s Largest Owl by Jonathan C. Slaght

- The Ministry for the Future by Kim Stanley Robinson

Hoi Ning Ngai, Associate Director, Center for Purposeful Work

Young Adult:

- Fable, Namesake by Adrienne Young

- Tweet Cute by Emma Lord

Other:

- Think Again by Adam Grant

- Minor Feelings by Cathy Park Hong

Kerry O’Brien, Assistant Dean of the Faculty

The Dutch House by Ann Patchett. My favorite book of the year. This is an amazing novel about sibling devotion, things that could have been, and unimaginable decisions that have ramifications for years. It’s cast as a fairy tale complete with an evil stepmother and a heartless father, but there are many twists and turns. It’s about obsession, memory, why it’s so hard to let go of the things that have been lost to us, and what we gain in the wake of what we lose.

A Long Petal of the Sea by Isabel Allende. The undercurrent to this novel is life under fascism (a theme of much of Allende’s work), but it follows the lives of two people flung together at the end of the Spanish Civil War. They escape to France and are evacuated on Pablo Neruda’s refugee ship to Chile, which transported thousands of Spanish exiles to Latin America. In Chile they build a new life, only to be met with the Pinochet regime and the complicit Church. It’s a political story told through the lives of compelling individuals and families over a long arc of time and generations.

Spying on the South: An Odyssey across the American Divide by Tony Horwitz. The late, brilliant Tony Horwitz was a journalist-historian whose books are smart and also hilarious. His M.O. was to infiltrate communities and relive historic events (c.f., Confederates in the Attic and Blue Latitudes: Boldly Going Where Captain Cook Has Gone Before) to get at the core of historical questions. In this book, he retraces the steps of Frederick Law Olmsted who, before he became the most famous American landscape architect (Central Park, Boston’s Emerald Necklace), was dispatched by The New York Times in the 1850s to investigate what life was life in the Deep South, as slavery was becoming a burning issue across the country. Horwitz follows the journeys Olmsted made, reflecting on FLO’s observations and reporting on his own view of the modern South, with a throughline of race, class, and geography. It is a fascinating book in these divided times.

Carole Parker, Library Assistant for Acquisitions

- Heavy and Long Division by Kiese Laymon

- A Long Petal of the Sea by Isabel Allende

- So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Oluo

- The Devil in Silver by Victor LaValle (thanks, Therí Pickens!)

- A Stranger in the Kingdom by Howard Mosher

- A Promised Land by Barack Obama

- The Cutting Season and Bluebird, Bluebird by Attica Locke

- Fear of the Dark by Walter Mosley

Mary Pols, Media Relations Specialist, Bates Communciations Office

For memoir, don’t miss Michelle Zauner‘s Crying in H Mart, the story of her difficult but delightful Korean mother, her life growing up in Oregon and visiting her mother’s family in South Korea regularly, and her mother’s battle against cancer. Zauner is an indie musician and the founder of Japanese Breakfast, but the book is never about her quest to make it in the music world; this is about trying to grapple with family, her own Korean-American identity and grief. Crying in H Mart takes off from Zauner’s popular essay of the same name that appeared in The New Yorker in 2018.

Notes on a Silencing by Lacy Crawford is powerful, but be warned it tackles a difficult subject head on. When Crawford was a teenager at St. Paul’s boarding school, she was violently sexually assaulted by a pair of older students. This is her story of being shut down and shamed by virtually everyone at the school, surviving and coming to terms with the privilege afforded her rapists and the misogyny directed at her. This is the kind of book that reveals the institutional sins of not-so-distant past and makes you want to fight for change.

A lot of people have likely already read this one, because it was a Maine Public read earlier this year (and on a lot of 2020 Best of lists) but Portland resident Lily King‘s novel Writers & Lovers is a subtle but firmly feminist novel about the creative process, romantic choices, waitressing to foot the bills while undertaking creative endeavors — in this case, writing a novel — and it is wonderful. I’ve shared this title with about a half dozen friends, all of them very different kinds of readers, and each of them has loved it.

Sea Wife by Amity Gaige is a fantastic summer read. A wife grudgingly agrees to her Trump-voting husband’s request that she and their kids join him on a year-long sea voyage on a sailboat. There’s suspense, a great portrait of a fraying marriage, and totally transporting settings.

Finally, a very recent release, The Plot by Jean Hanff Korelitz. Perfect for writers, those who love them and those who might want to understand them better. The main character is Jacob Finch Bonner, a once-promising novelist, now washed up and teaching at a low-res, low-self-esteem MFA program in Vermont, part time. (He added that Finch for flash, fyi.) A new student, Evan Parker, brags about his unfinished novel and how its plot is so good it can’t possibly fail when it is eventually published. A few years later, Jacob discovers something that makes that plot very tempting to him. No book about writing should be this much of a page turner, but this one is that and relentlessly entertaining and smart.

Sarah Potter ’77, Bookstore Director Emerita

Chickens, Gin, and a Maine Friendship: The Correspondence of E.B White and Edmund Ware Smith by E.B. White and Edmund Ware Smith.

Ahhh, I do love E.B. White! Throughout the late ’50s and ’60s, these two writer-farmers exchanged humorous and lively letters. Here White reflects on Smith’s new henhouse: “The domestic egg is the beginning of your doom…first the henhouse, then the egg, then the grain bill, then the full corn in the ear, and the bulldozer to break trail for the grain truck…That first egg, so deceptively beautiful, so germinal! I bought this place because it had a good anchorage for a boat. One day I noticed it had a barn. Now I don’t even have a boat.”

Continuing the theme of farming life in Maine, I read Lost Paradise: A Boyhood on a Maine Coast Farm by R.P.T. Coffin, poet/author, Pulitzer-prize winner, Bowdoin professor. I was charmed by his recollection of Harpswell/Brunswick life in the early 1900s. His story could easily have been my grandparents’ tale of growing up in Downeast Maine. Reading this book prompted me to find Coffin’s beautiful headstone at Cranberry Horn Cemetery in Cundy’s Harbor (in January!). Coffin family roots are broad and deep in this part of Maine.

I was surprised by another good read, Bad Beaver Tales: Love and Life in Downeast Maine by midwife, writer and beaver-trapper Carol Leonard. She was just the hilarious storyteller I needed this past year.

Of course, I read and loved Louise Penny‘s annual Armand Gamache mystery, this one called All the Devils are Here. Not her best, in my view, but it was still a great read.

And finally, I have just finished The Four Winds by Kristin Hannah. This compelling novel paints a vivid picture of the devastation of the Dust Bowl.

Jack Pribram, Professor Emeritus of Physics and Astronomy

How to Tame a Fox (and Build a Dog): Visionary Scientists and a Siberian Tale of Jump-Started Evolution by Lee Alan Dugatkin and Lyudmila Trut. In the late 1950s the scientist Dmitri Belyaev had the idea that if dogs came from wild wolves, maybe dogs might also come from passive wild foxes. Lyudmila Trut offered to go to a farm in Siberia to raise silver foxes and annually mate the passive ones. By the sixth and later generations some would change colors, ‘bark’ and behave much like dogs. Trut and others still work on this. She is now in her late 80s. Working in the Soviet Union and Russia caused problems off and on.

Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past by David Reich. It’s only been a dozen years or so that ancient DNA could be obtained from bones going back over tens of thousands of years, not only of Neanderthals, but recently discovered Denisovans. One big surprise was that so many humans did not always stay in one place; there were large populations moving. People going from India to Europe; people going to East Asia; people going from Siberia to America; and so on. Maps and charts for each chapter makes it possible to get a clear sense of the complexity of what was happening.

Darby Ray, Director of the Harward Center for Community Partnerships

I highly recommend Argentine author Mariana Enríquez‘s 2016 short story collection The Things We Lost in the Fire (the English translation, by Meghan McDowell, is beautiful). Enríquez creates rich, haunting universes within each story.

Stephanie Pridgeon, Department of Spanish

I recommend Thrown in the Throat by Benjamin Garcia. An amazing first book by a queer Latinx poet whose way with words I cannot adequately describe. You could spend your summer in one poem.

Erica Rand, Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies

My guilty pleasure during the first half of the pandemic was reading Tana French‘s crime mystery novels, which I thoroughly enjoyed. In other genres and for quite different reasons, both Lily King‘s Euphoria and Isabel Wilkerson‘s Caste made an impression.

Kirk Read, Professor of French and Francophone Studies

Indeed, I’ve read a lot more this year and offer some suggestions from various spheres and journeys.

Isabel Wilkerson’s book Caste is on the bookshelves of many friends and talking heads that I listen to and watch and I highly recommend it. As with many works striving to wake us up to systemic racism, it is a retelling of American history with a new lense that helps make the scales fall from one’s eyes. When the Nazis went looking for a plan to segregate and exterminate, the monster they came to for a model was the United States. I’m still left with questions about what the legacy of privilege and entitlement means in this scheme, but it was a page turner.

I went down a rabbit hole with Walt Whitman whom I had not read in too long. My editions of his works had turned to cornflakes. My way in was Mark Doty‘s What is the Grass: Walt Whitman in My Life which is a poet and teacher’s rumination of all that this poet has meant to him professionally and personally. Inspiring. Whitman’s queerness is so beautiful, ebullient, and multi-faceted. Shifting between Doty, Whitman’s works and the Justin Kaplan biography (Walt Whitman: A Life) was a joy.

Recruited once again for a theatrical endeavor, I was prompted to research into Dominican culture in the Bronx (the play is Heidi Schreck‘s Grand Concourse — that being the borough’s main drag); Jewish life in the same neighborhood; and an education in schizophrenia and other mental illnesses which plague my very colorful character.

And so, Angie Ruiz‘s Dominicana tells a vivid story of several generations of Dominicans living and migrating between the DR and NYC; E.L. Doctorow‘s World’s Fair, is a beautiful, tender retelling of a Jewish boy’s life in the light and shadow of the 1939 World’s Fair on the cusp of World War II — as a man reading this through a boy’s retelling, I found it remarkably touching and insightful; and one of my favorite books by far: Sandy Allen‘s A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise: a True Story About Schizophrenia, wherein the author tells of their uncle’s tormented journey through a life with schizophrenia and how it repelled, challenged, and enlightened a family—their uncle sent them a manuscript which Allen then blends with their own perspective, augmented with interviews and research. I emerged from that book transformed in the way I think about “craziness” and mental illness. They are also a deeply committed sourdough bread maker with the most joyful Youtube video coaching imaginable.

And circling back to Heidi Schreck, I cannot recommend her Pulitzer Prize Winning play, What the Constitution Means To Me, enough. It is also streaming and is simply amazing. Both this and Grand Concourse deal with reckoning and forgiveness with flawed families, governments, and well- meaning communities of all stripes who do not always triumph.

From my more academic shelf, I’m rereading Albert Camus‘ Le Premier Homme which I am just loving. Again, as with Doctorow, the voice of a sensitive boy’s experience (here in a very poor family in Algiers pre- independence) is stunning. The work was unpublished upon his untimely death in a car accident and was pieced together with some notations. Those who only know L’Etranger (The Stranger) from high school lit or French class will be surprised. Yes, it’s better in French, but it’s called The First Man. I am rereading all of Frantz Fanon‘s works, which as with so many amazing writers on race and colonialism from the past, come back with great urgency and wisdom in light of the year we have endured. Many know of this psychiatrist from Martinique who worked extensively in Algeria for The Wretched of the Earth. There is much more to recommend.

Tiffany Salter, Visiting Assistant Professor of English and Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies

I think, like many, I read more for pleasure this year. Here are some of the best since the last Good Reads came out. We Are Watching Eliza Bright by A.E. Osworth. A gripping thriller about a woman working in the male- dominated video games industry and the “fans” who punish her for speaking out against workplace harassment. If you followed “Gamer Gate” at all, this is a book for you.

All You Can Ever Know by Nicole Chung. A wonderful memoir about growing up as a Korean American adopted by white parents.

My Sister, the Serial Killer by Oyinkan Braithwaite. A strangely fun quick read about cleaning up after family mess.

Sansei and Sensibility by Karen Tei Yamashita. Short stories from over Yamashita’s long career primarily as a novelist. It is fun to see how her style has evolved through the years. The second half features contemporary takes based on each of Jane Austen’s novels featuring Japanese American characters.

Enter the Aardvark by Jess Anthony ’96. What a wild and fun ride from one of Bates’ very own professors!

If summer means epic fantasy to you, then I recommend these by Ken Liu: The Grace of Kings, The Wall of Storms, and the third one in this series (The Dandelion Dynasty), will be out November 2021, The Veiled Throne.

The Name of the Wind and The Wise Man’s Fear by Patrick Rothfuss.

Sharon Saunders, Associate College Librarian for Systems and Bibliographic Services

Why Buddhism is True: The Science and Philosophy of Meditation and Enlightenment by Robert Wright. Don’t be put off by the title of this book. It looks at things we have learned from evolutionary biology/evolutionary psychology to help explain why the mind works the way it does. It finds parallels in the Buddhist teaching of the three marks of existence:

impermanence, suffering, no-self (e.g., all we experience is impermanent, denying this creates suffering, thinking there is a separate self in charge — telling our bodies what to do and our minds what to think — also creates suffering). It then offers techniques for recognizing the workings of the mind instead of being caught up in the workings of the mind.

Hunt, Gather, Parent: What Ancient Cultures Can Teach Us About the Lost Art of Raising Happy, Helpful Little Humans by Michaeleen Doucleff. A very interesting and easy-reading book that puts our Western way of child- rearing into perspective.

Paula Schlax, Department of Biochemistry and Chemistry

I strongly recommend A World on The Wing: The Global Odyssey of Migratory Birds by Scott Weidensaul. How does a bird adapt to make an 18,000-mile round trip journey? Fly 6,000 miles over about eight days, non-stop? How do the birds know where to go? What happens when their stopover places are being developed by humans? How is global climate change influencing the migration patterns?

Johanna Seltzer ’03, Senior Associate Dean of Admission and Director of Special Projects

Burnout: The Secret to Unlocking the Stress Cycle by Amelia Nagoski and Emily Nagoski. Particularly timely for an intense period in our lives!

Especially relevant for women, working women, working mothers. Emily (a faculty member at Smith) has a great way of bringing in scientific knowledge and research to make her advice evidence-based, but digestible. The book is funny, practical, and good — and typically, I really hate self-help books!

The Road from Coorain by Jill Ker Conway. A lovely autobiography of Conway’s upbringing in Australia. Escapist and relatable, at the same time. It’s a wonderful, easy read about a young person, coming into her own as an intellectual, a leader, and a woman.

Anthony Shostak, Education Curator, Bates College Museum of Art

Democrat to Deplorable: Why Nine Million Obama Voters Ditched the Democrats and Embraced Donald Trump by Jack Murphy. If you don’t understand how a liberal can be a conservative voter, this book might help you understand some of the many complex reasons, in a format that feels like conversations with neighbors.

Apocalypse Never: Why Environmental Alarmism Hurts Us All by Michael Shellenberger. Written by a former professional activist, this book invites one to rethink their settled thinking on environmentalist strategy, policy, and initiatives.

Clayton Spencer, President

Go, Went, Gone by Jenny Erpenbeck. Set in contemporary Berlin, it is the story of a university professor who is a bit at loose ends when he retires after a long career and how he stumbles into finding meaning in his new life by engaging with a group of African refugees who have landed in Berlin. The writing is spare and sublime. The underlying story is powerfully humanistic.

One of the best books I have read this year.

Kika Stump, Learning Assessment Specialist, Office of Institutional Research, Analysis, and Planning

I’ve been reading some great YA to keep up with the teenager in the house: Black Enough: Stories of Being Young and Black in America, edited by Ibi Zoboi; Kira Kira by Cynthia Kadohata; and Brown Girl Dreaming by Jacqueline Woodson.

On my own list, (nonfiction) As We Have Always Done by Leanne Bettasamosake Simpson has kept me going while, (fiction) Washington Black by Esi Edugyan was a powerful adventure novel.

Sawyer Sylvester, Professor Emeritus of Sociology

The Joy of Walking by Suzy Crips is a collection of comments on their walks by well-known figures in English literature.

The Twilight of Democracy by Anne Applebaum is a sobering account of the rise of the modern despotic state.

For two accounts of that highly intelligent (and occasionally playful) ocean dweller, I recommend Octopus: The Ocean’s Intelligent Invertebrate by Mather, Anderson, and Wood, and The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgomery.

The Black Mozart, le Chevalier Saint George by Walter E. Smith is about “a great fencer, a composer, conductor, virtuoso, an artful equestrian, an exceptional marksman, an elegant dancer, an accomplished man of his time….” (1739–1799).

Legacy of the Sacred Harp by Chloe Webb is an account of a personal quest of the author for a link between her extended family and the Southern tradition of American shape note singing.

The Louvre by James Gardner is a political history, from fortress to palace of the world’s most famous museum.

Bill Bryson’s The Body is an engaging and immensely literate account of human anatomy and physiology.

Daniel Silva’s The Order is probably the best of his Gabriel Allon mysteries so far.

Finally, Henry Beston’s Herbs and the Earth is an account, both historical and personal, of his and our relationship to the world of herbs. One should also enjoy the woodcuts by John Hudson Benson.

Anne Thompson, Professor Emerita of English and Euterpe B. Dukakis Professor Emerita of Classical and Medieval Studies

Hamnet by Maggie O’Farrell. A novel about Shakespeare and his family. It’s a fiction, but some basic aspects of it are true: Shakespeare did have three children, two of whom, Judith and Hamnet, were twins. Hamnet died at 11, for unknown reasons.

O’Farrell imagines the relationship between Hamnet’s death in 1596 and the writing of Hamlet, circa 1600. His wife, about whom we know very little, is wonderfully portrayed as an uneducated but gifted and insightful healer with much of the book seen through her eyes. I couldn’t put it down.

Stephanie Wade, Lecturer in Humanities and Assistant Director of Writing

- The Overstory by Richard Powers

- There, There by Tommy Orange

- On Earth We’re Briefly Gorgeous by Ocean Vuong

Dick Wagner, Professor Emeritus of Psychology

Jill Lepore‘s These Truths is the most enlightening and best written US history I’ve ever read. It’s long but well worth the effort. Tells you things and provides contexts the standard history books “forgot” to mention.

William Wallace, Lecturer in Education

Elizabeth Kolbert‘s new book, Under A White Sky: The Nature of The Future. She was our Otis Lecturer a few years ago after she won a Pulitzer Prize for The Sixth Extinction. Elizabeth makes complex science understandable, urgent, and enjoyable to read. She’s wonderful!