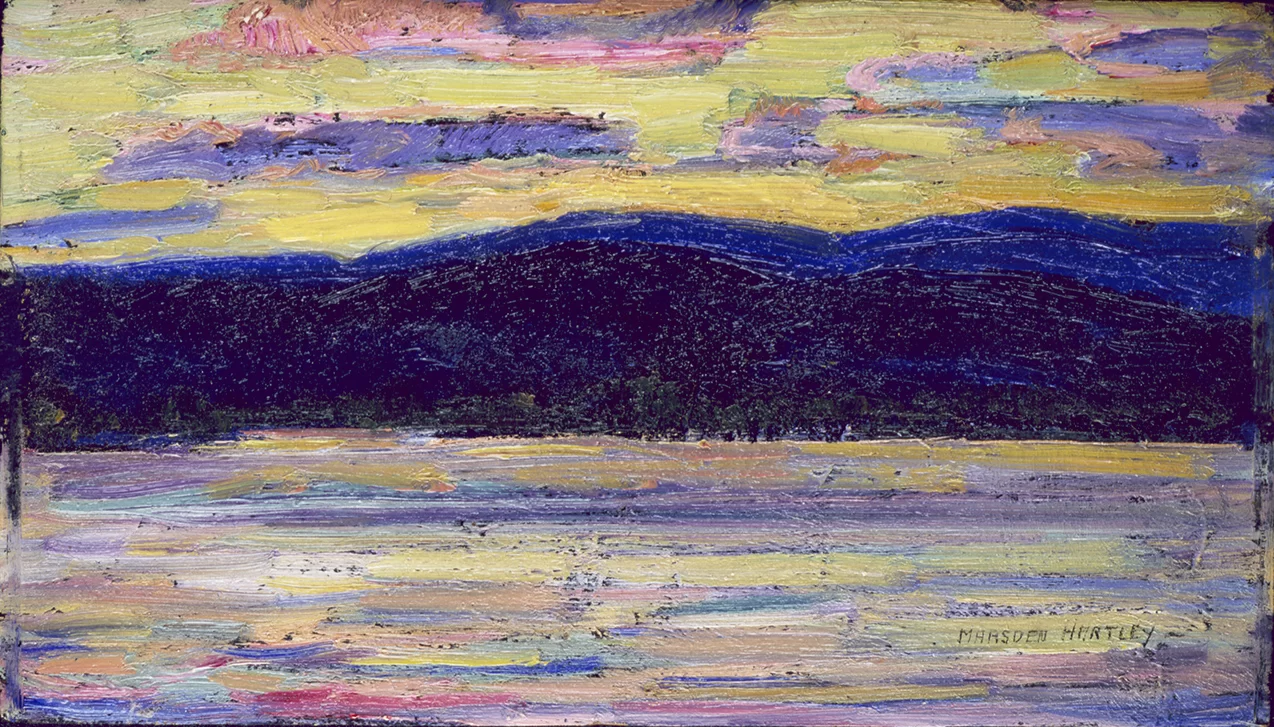

Marsden Hartley, the famed modernist artist who was born in Lewiston in 1877, was a lifelong traveler and wanderer who collected mementos everywhere he went — from seashells to bracelets and rings.

Those souvenirs influenced his art, and vice versa, a dynamic that gives nuanced meaning to the exhibition Marsden Hartley: Adventurer in the Arts now at the Bates College Museum of Art.

At its center, of course, is Hartley’s artwork, more than 35 paintings and drawings, including all 22 Hartley works in the collection of Jan and Marica Vilcek, which are presented alongside personal objects and keepsakes from the artist’s life of adventure and travel.

Exhibition Catalog

The exhibition catalogue for Marsden Hartley: Adventurer in the Arts is available through the Bates College Store. As of Sept. 24, the Bates Museum of Art is open only to members of the Bates community with a valid Bates ID.

Rick Kinsel, president of the Vilcek Foundation, where the exhibit will travel next, calls Hartley “a trailblazing American multiculturalist.” The exhibition demonstrates that and more, while acknowledging Hartley’s love of his home state, and the influence his hometown had throughout his life.

And some of it might surprise you. Because distance and the pandemic might prevent you from visiting the museum in person, we like to share these 13 nuggets from a gem of an exhibition — so you can experience a bit of Marsden Hartley, wherever you are.

His niece planted the seed for this exhibition 70 years ago

In 1951, four years before Bates dedicated its first art exhibition space, Treat Gallery in Pettigrew Hall, the family of artist Marsden Hartley designated Bates as the recipient of his possessions from his last days as an artist.

The possessions included everything that had been in his studio in the Down East fishing village of Corea, where he lived and worked until his death in Ellsworth in 1943.

It was a gift with a mission; his niece, Norma Berger, the closest relative the Lewiston native had, and who had herself been the regular recipient of souvenirs from her uncle’s extensive travels, told Bates that Hartley had wanted to leave a collection for “the boys and girls of Maine.”

Berger said that Hartley told her how “barren” his childhood and young adult life had been of “anything that he might have studied along that line.” Hartley, she continued, “cherished the hope that he could provide some such collections which would be helpful to the children of his native state.”

Four years later, Berger added to the gift, with a collection of her uncle’s work, including 99 drawings, some early oil sketches and some poems. There were also antiquities, textiles, and memorabilia in the collection.

At the time of Berger’s gift, Hartley was all but forgotten in Maine

But during his lifetime, he had deeply wanted to be known as a Maine artist. He referred to Maine as “his continent” and to himself as “the painter from Maine.” He hoped to live on in history as one, connected to Lewiston. At the time of his death, his ashes, by his wishes, were scattered on the Androscoggin River.

In making this gift, rich not in canvases but in its markers of Hartley’s passions, Norma Berger thought ahead, writing to Bates: “The collection was of no great intrinsic value and could hardly have meant much to any institution as such, but the time will come when a memorial collection will have its significance.”

He learned to love the circus in Lewiston and remained artistically obsessed with it

Born in 1877, in Lewiston, Hartley had an impoverished childhood and lost his mother when he was only 8. The nature surrounding his native city captivated him while “the harsh grinding of the mills rang in my ears for years.”

But so did the warm memories of the circus coming to Lewiston — and the annual Maine State Fair at the Lewiston fairgrounds. Hartley’s cousin owned and operated a theater in Lewiston, which furthered his connection to performance.

At 16, he moved to Cleveland, Ohio, to be with his father and his father’s new wife. Later, as a young man, Hartley moved to New York and attended the circus in Madison Square Garden. On a trip to Paris, he saw the circus at the Cirque d’Hiver. His love of the circus even landed him a byline in Vanity Fair (in 1924, for a poem about the circus). He was particularly fascinated by acrobats, who he wrote knew how to “decorate the space on which he operates.”

One of the big canvases lent to the Bates museum by the Vilceks is The Strong Man, a direct reference to the circus, painted in Berlin, likely in 1923. A drawing of an elephant in the Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection at Bates was likely made during multiple attempts Hartley made to design a cover for a planned but unfinished book called Elephants and Rhinestones: A Book of Circus Values.

Hartley hoped that if there was an afterlife, a heaven, that in it, he could join “the splendid horde” of circus performers, on “what will no longer be ‘The Greatest Show on Earth.’”

Hartley was broke, just about all the time

The famed photographer Alfred Stieglitz helped fund Hartley’s first trip to Europe in 1912. Hartley had been longing to go. “One day it all came like magic and I knew I could go, and there was my first voyage into the world of dreams and legend,” he wrote in his memoirs.

In the next decades, he would regularly travel, staying in the homes of friends or finding cheap places to rent, until the money ran out. He visited, among other locales, Germany, Austria, Italy, Bermuda, Mexico, and Canada.

But he was at peace with his lack of money

Anyone with money problems knows how hard it is not to focus on them. But Hartley was at peace with it, near the end of his life writing to Berger: “When I am no longer here my name will register forever in the history of American art….O the difficulties — all monetary of course because the rest is pure satisfaction — joy — and a feeling of having gone where one was headed for.”

Hartley was enterprising

He once wrote that he didn’t even need a real studio, just a room “any kind of room” and two chairs, one of which he’d sit on and the other, he’d use as an easel.

When it came to materials, he made do. In 1933, he traveled to the Alps and spent seven intense weeks walking to make sketches for paintings. He wrote to Berger that he’d nearly finished 15 paintings in seven weeks, but had switched to painting on cardboard “because I can’t afford canvas but I like cardboard so no call for pity then.”

He was a souvenir hunter

He collected inexpensive mementos that he treasured, picking up objects and artifacts everywhere he went.

He loved seashells (there are paintings of a few in the exhibition). He sought out jewelry, including bracelets with his initials and rings. “We don’t really put our initials on things as much anymore,” says museum registrar Corie Audette, pointing out some German cufflinks and a cigarette case, emblazoned with the “MH.”

In Hartley’s memoirs he called his collecting an alternative to “concrete escapades” — a reference to his life as a sexually repressed gay man—and his own preference for abstract escapades (“the collecting of objections which is a sex expression too the upper hand,” he wrote.)

He never owned a home of his own

While he was happy being a nomad, late in life he did have thoughts of building a home in Corea, where his art could be shown next to his beloved treasures. He gave the place a name, High Spot, and drew up plans for it. He gave up the idea, but those plans are in the Marsden Hartley Memorial Collection at Bates.

His souvenirs influenced his paintings, and vice versa, regularly

The red and black blanket, probably Mexican, that is part of the exhibit, seems echoed in the motifs and palettes of paintings like Christ (1942), one of many religious images he finished in his last years.

Intellectual Niece, owned by Bates, was painted either in West Brooksville, Maine, while Hartley was visiting friends, or shortly after that visit. It features the Bagaduce River in the background, with sailboats coming in and out of the frame, and a man looming in the middle, two women seated on either side of him.

But the composition seems very reminiscent of an Egyptian textile fragment (likely from a garment) Hartley purchased in his travels. Bates museum curator William Low has placed them together in the show. “Some scholars really think that these images influenced his painting,” Low says. “And so the reason I have this here is because this is a late figure work that he did, and I see a clear connection between the things that he was looking at and his work”.

One of these paintings has never been exhibited in the U.S. before

Schiff (ship or boat), a large painting with a frame that Hartley decorated as well, extending the work off the canvas, was painted in Berlin in 1915. But before the Bates show opened this week, it had not yet been shown publicly in the U.S.

“That’s a big deal,” says Low. The painting’s central image looks more like a Native American canoe — with a bit of a circus vibe — than a ship. But in the exhibition catalogue, Rick Kinsel, the president of the Vilcek Foundation, suggests that Hartley may have been thinking of the solar ship of the sun god Ra in ancient Egyptian mythology. (Look closely at the bottom right part of the frame and you’ll see a horizontal red zigzag, the Egyptian hieroglyph for water.)

The painting was directly inspired by Hartley’s early travels. After Paris in 1912, he went to Germany in January 1913, with a German sculptor friend named Arnold Ronnebeck. He fell in love with Ronnebeck’s young cousin, an officer in the German military, and was captivated by the Kaiser’s many military parades, which featured men in white leather breeches on white horses, and held an erotic charge for him.

In his memoirs he wrote of the allure of the parades, “six foot of youth under all this garniture,” and how they brought the attraction back to childhood memories of circus parades in Lewiston.

Experts marvel at the varied styles of Hartley’s work

Jan and Marica Vilcek can’t quite believe how much his work varies in style. “It’s hard to fathom that works as diverse as Mont Sainte-Victoire and Schiff were painted by the hand of the same artist,” the couple says in the preface to the exhibition catalogue.

“Among all the American modernists we have collected, Hartley stands out not only for the diversity, beauty, spirituality, and mystery of his work, but also for his openness to other cultures and ways of life.”

The adventurer left Maine a lot, but he always came back

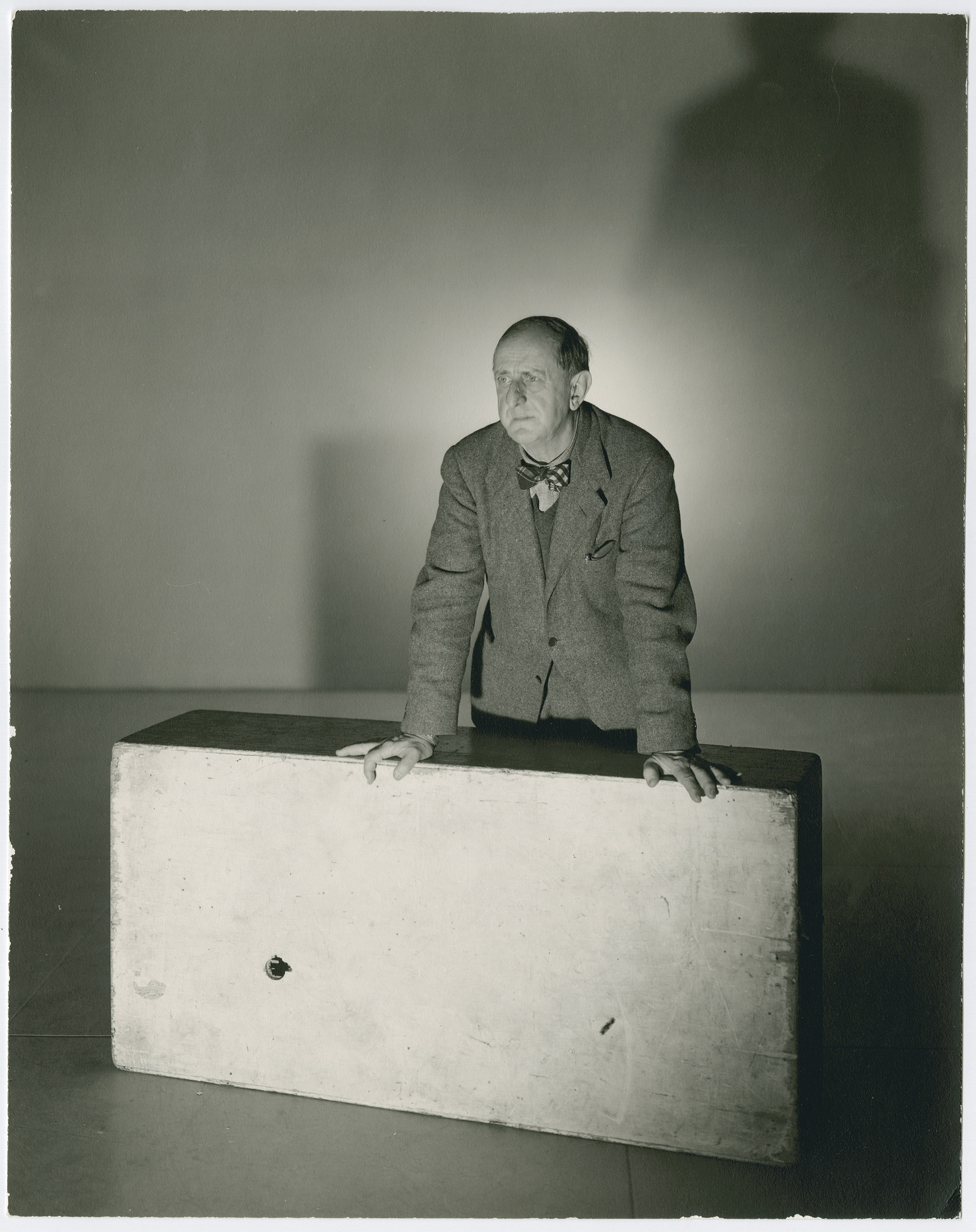

The first recognition Marsden Hartley got for his work were for paintings he made in North Lovell, near the shores of Kezar Lake, in 1908. While he traveled extensively, particularly in Europe, and made famous friends (like Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas, and the photographer Man Ray, who made his portrait, also in the exhibit) he always came home to Maine, the place he told Stieglitz was “the country that taught me how to endure pain.”

He’s also famous for his landscapes of Katahdin

He took his first trip to Baxter State Park in October 1939. The park, founded in 1931, was still very new.

Hartley got a ride to “the foot of the mountain” and in a letter to his niece, described his walk to his camp: “four miles to walk — in the dark through the rain — pitch black and the worst road I ever encountered in my life.”

Eight days in Baxter cost Hartley $40. He came out with four paintings and a wish fulfilled. “I got my sacred mountain in the end….” He also got his wish, that his name would be forever associated with Maine and the mountain.