What do hemp, centuries-old squash seeds, and a lake of carefully tended wild rice have in common? The future, according to environmentalist, economist, writer, and activist Winona LaDuke.

The coronavirus pandemic has changed economies globally, crippling large and small businesses alike. Supply and demand never seem to match, and countries’ unwillingness to give up fossil fuels has delivered a setback to the world’s climate change goals, while increasingly extreme weather events — drought, heat, floods, and rising ocean waters — underscore the need to take action.

Even with modern and sustainable methods of generating power, conserving water, and consuming more efficiently, not all the solutions we need are new. Sometimes, reaching back into the past and consulting the cultures who lived here before us — and live here today alongside us — can reveal the answer we’re all looking for.

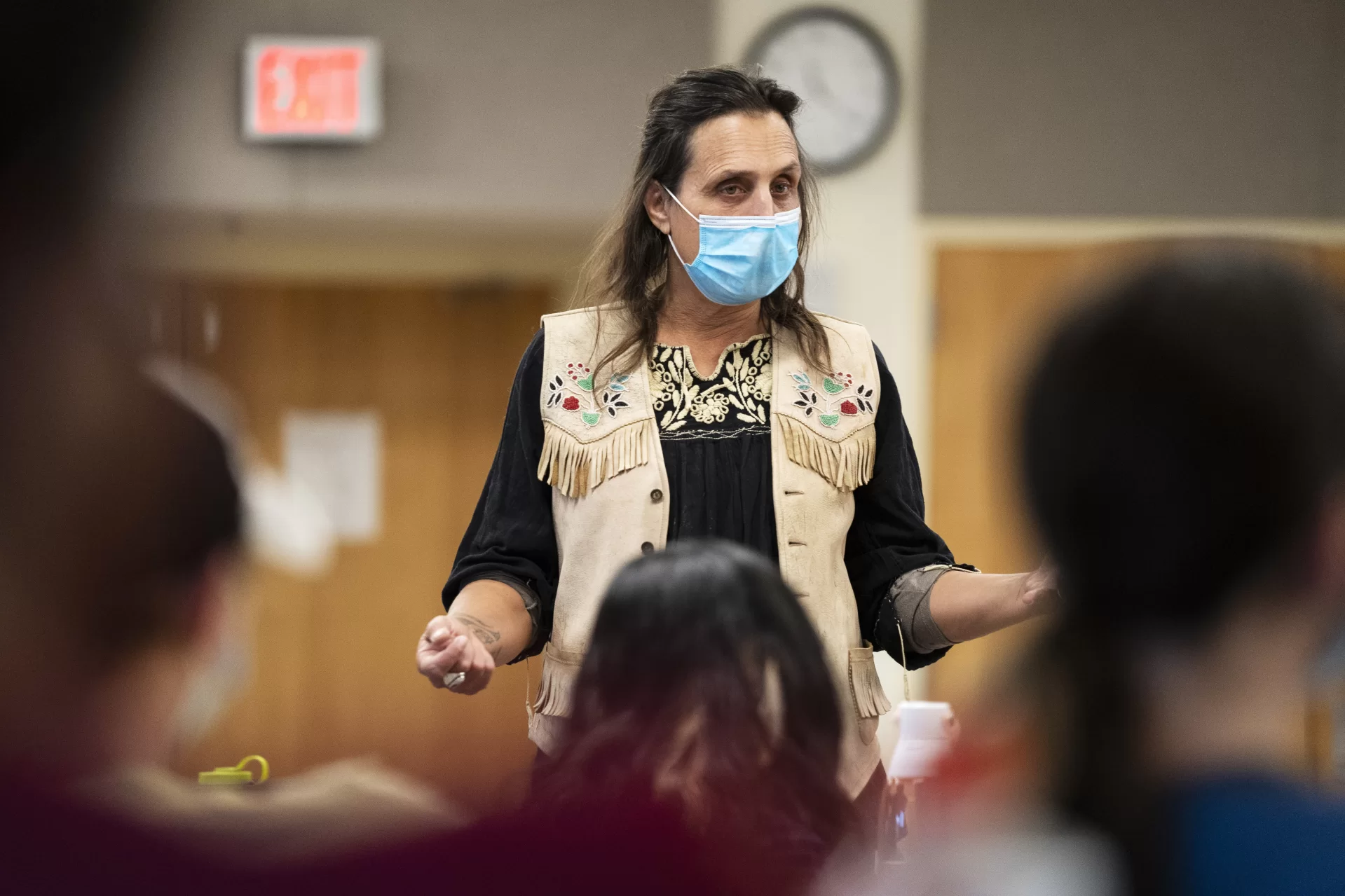

That was LaDuke’s message last Monday while delivering Bates’ 24th annual Otis Lecture, “The 7th Fire and a Just Transition: Indigenous People and the Next Economy.”

LaDuke is a member of the Ojibwe people, part of the larger Anishinaabe group of North American Indigenous cultures. The “7th Fire” of her talk’s title draws from Anishinaabe prophecies made 500 years ago. Our troubled world is in the time of the Seventh Fire, she explained. The promise of a sustainable, green, and socio-economically just future is the Eighth Fire, and LaDuke wants us all to be ready for it.

“We were told that we would have a choice in the time of the Seventh Fire between two paths,” said LaDuke. “It said one path would be well-worn and it would be scorched. And the other path would not be well worn; it would be green. They said, ‘You need to make a choice between two paths.’ And I would suggest to you that that is not actually just an Anishinaabe conundrum: I think that’s really an American conundrum.”

“We have some experience with sustainability. I would suggest to you that the U.S. does not.”

Few with any environmental awareness would argue against the dire need to create some sort of post–fossil fuel world, with an intentional shift toward solar power, greater sustainability in food and materials, and protection of natural resources.

But getting there? That’s the rub. And from LaDuke’s perspective and expertise as an Indiginous activist, one of the many crimes of American colonialism is how it has systematically pushed aside — and tried to erase — sustainable and effective practices and ways of life.

For example, the Ojibwe people have harvested the same crop of lake-grown wild rice for over 10,000 years, bringing in up to 500 pounds of rice a day “with just two sticks and a canoe,” LaDuke said.

That, she added, is an example of what sustainability is. “You take care of your lake, make sure the water levels are good. So we have some experience with sustainability. I would suggest to you that the U.S. does not.”

To illustrate that point, LaDuke often tells the story of when anthropologists visited the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota to study Ojibwe rice-harvesting practices and left with a disdain for the limitations of its simplicity. In The Wild Rice Gatherers of the Upper Lakes, published by the Smithsonian Institution in 1900, it is said that “wild rice, which had led to their advance thus far, held them back from further progress, unless, indeed, they left it behind them, for with them it was incapable of extensive cultivation.”

The point is, Indigenous practices and ways of life are presented as a thing of the past, says LaDuke. Methods of growing and gathering food, building communities, and sharing culture are often seen as outdated and inefficient. Producing food for local — and not global — communities without an eye toward commercialization doesn’t fit what many of us see as progress.

Wild rice is also central to another of LaDuke’s themes, biodiversity. “In this world that we’re in today, it is essential for all of us to protect where the wild things are,” LaDuke said. “That’s where I say I live: where the wild things are. And that is how we survive: by protecting biodiversity.”

Around 13 years ago, LaDuke was given some very old squash seeds. (There are a few stories about their origin.) She gave some away and planted the rest and they yielded big, bright orange, bumpy squash, now a heirloom variety, which LaDuke named Gete Okosomin, meaning “really cool old squash.”

Even centuries-old seeds remember how to grow, and those ties to the earth can help create stronger, more diverse crops. “The solutions are to grow local, and to grow indigenous varieties,” LaDuke said.

“The next economy should be owned by the people who didn’t benefit from the last one.”

Hemp is another example of a once-powerful economic driver that was relegated to throwback status. Industrial hemp was used to make a variety of industrial and consumer products, including textiles. LaDuke has said that “anything that you can do with fossil fuels you can do with hemp, plus more. Just think about the fact that the word ‘canvas’ comes from cannabis.”

Then, in 1937, industrial hemp was made illegal. “About 100 years ago, we had a choice between a carbohydrate economy and a hydrocarbon economy,” she added. “And we made a wrong choice.”

LaDuke grows hemp on her farm near Callaway, Minn. She’s cultivating it as a perennial, which means that she’s not focusing on the CBD properties but the plant itself, and the way it interacts with the soil. Growing hemp perennially means it can sequester carbon in the soil for longer, and the plant is healthier.

As CBD products continue their march into the marketplace and hemp potentially replaces more fossil-fuel plastics, LaDuke believes the people at the forefront of those industries should be Indigenous and people of color, asserting that “the next economy should be owned by the people who didn’t benefit from the last one.”

LaDuke’s recent activism includes her efforts to fight the expansion of the Line 3 pipeline in northern Minnesota. The pipeline carries tar sands, a type of heavy crude oil. Replacing and building new pipelines to transport tar sands continues to power the demand for unsustainable energy while ignoring Indigenous land rights and the climate crisis.

Indeed, there’s still no coherent energy framework in the U.S. that accounts for climate change and its disasters, LaDuke said. “There’s no plan.” And with no national plan, it can be difficult to see any action that can be taken, outside of political and social activism. Which returns her to the promise of the Eighth Fire.

LaDuke quoted Indian author and activist Arundhati Roy:

“Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging the carcasses of our prejudice and hatred, our avarice, our data banks and dead ideas, our dead rivers and smoky skies behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.”

“You have an opportunity to transform things,” LaDuke said. “The question is, what can you do in those moments? What do you learn from them? How do you adapt?”