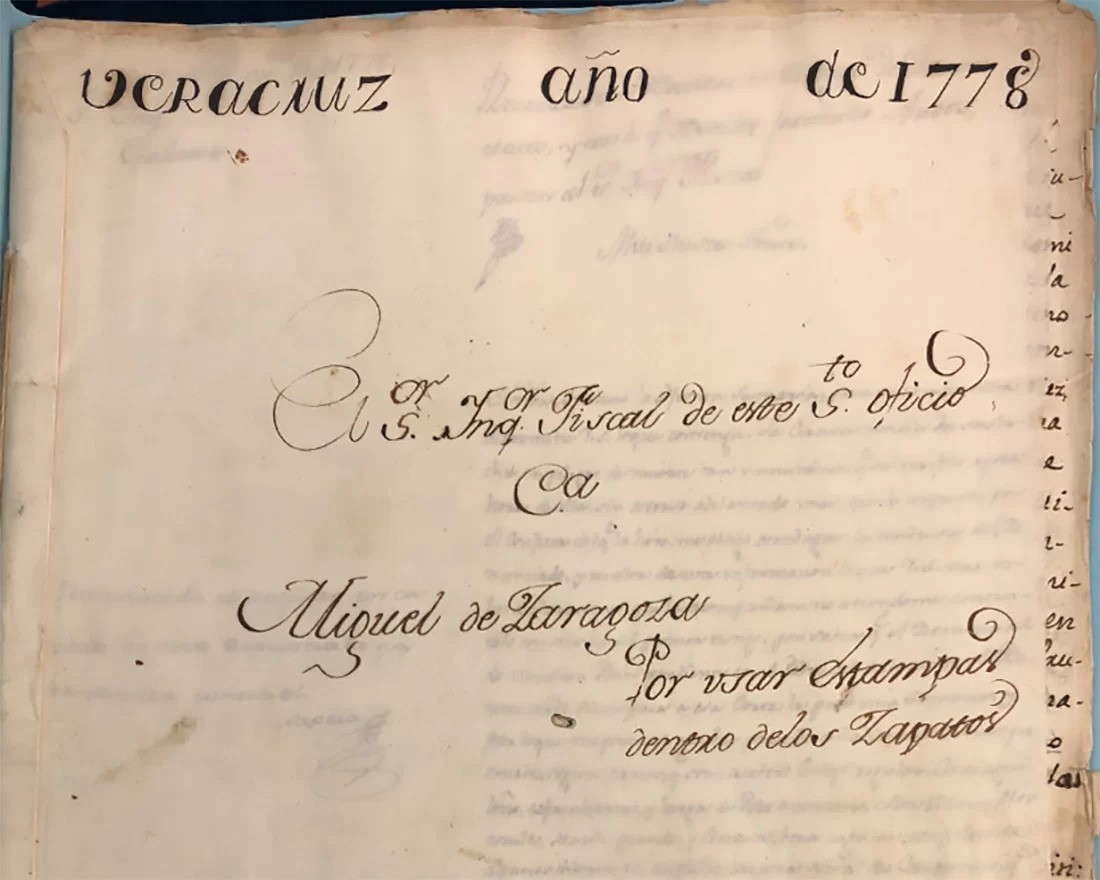

On his deathbed in Veracruz, Mexico, a man accused his acquaintance of this act of blasphemy: “Usar dentro de los Zapatos, unas Ymagenes que le parecieron de Santos.”

The accusation, translated from the Spanish: “Using in his shoes certain images that appeared to be saints.”

The year was 1778, when putting printed images of saints, known as estampas, inside your shoes could get you swept up in the Spanish Inquisition, the tribunal established to root out and punish acts of heresy throughout the Spanish Empire.

Running from 1478 to 1834, the Inquisition operated through fear and ruthless efficiency, at least according to Monty Python, prosecuting an estimated 150,000 people for various offenses and executing between 3,000 and 5,000.

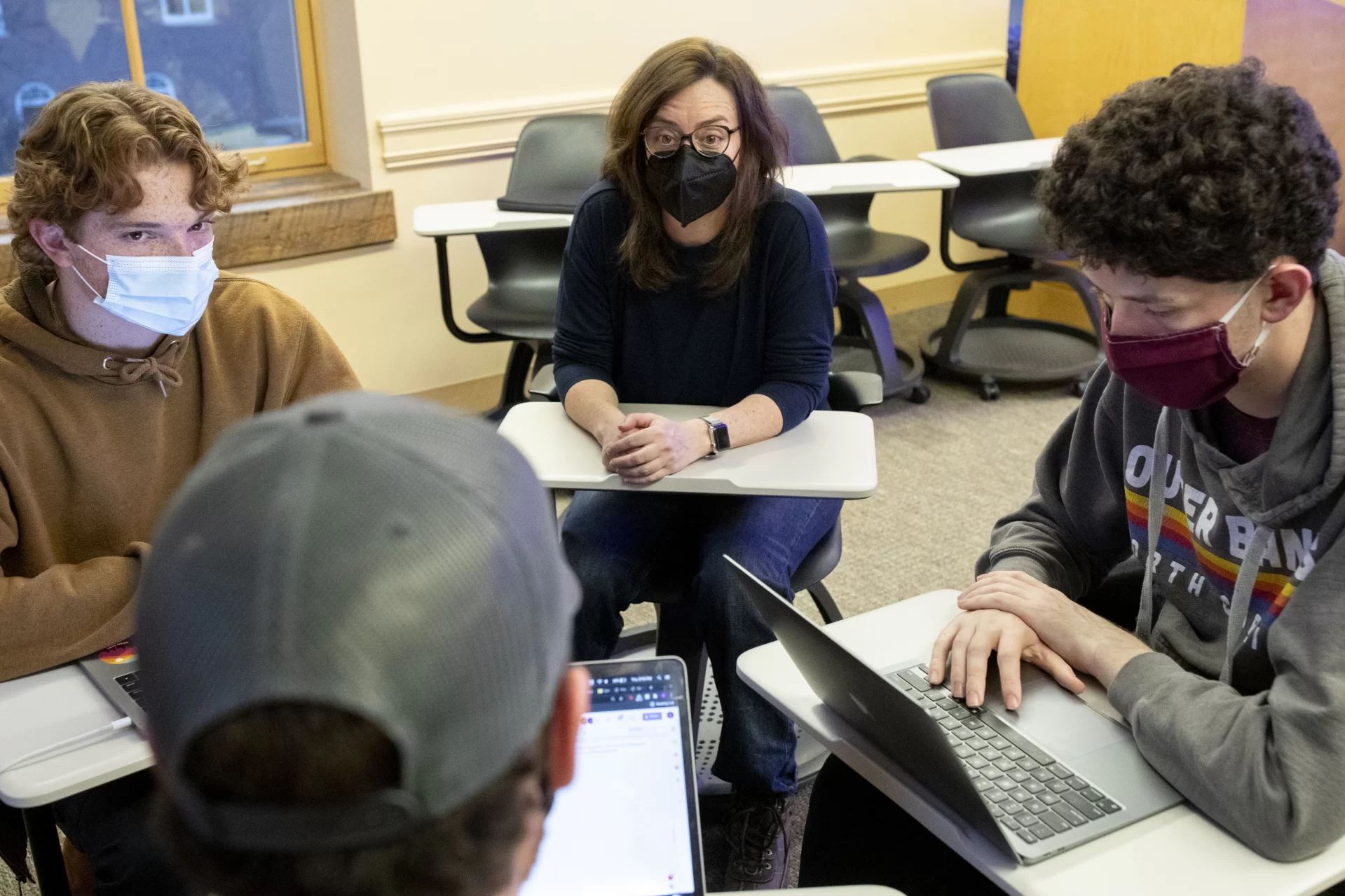

Now, thanks to a first-of-its-kind website co-founded by Bates Professor of History Karen Melvin, you can read all about the inquisition of Don Miguel de Zaragoza, an 18th-century silversmith accused of wearing unsensible shoes, as well as other cases of the Spanish Inquisition.

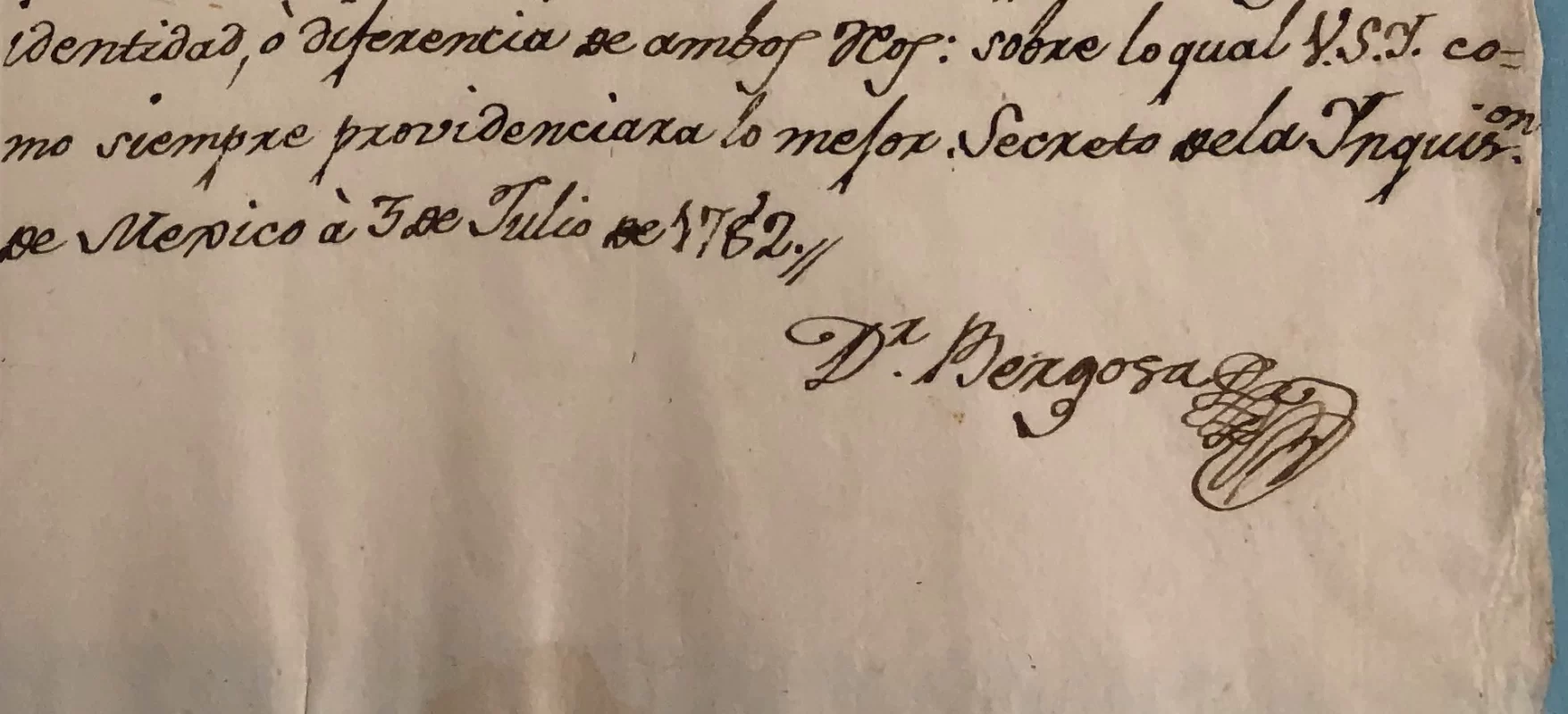

The website, Reading the Spanish Inquisition, is distinctive for displaying source materials in three different formats: images of original Inquisition documents; text transcriptions into Spanish; and English text translations prepared by scholars.

While there’s no shortage of Inquisition source materials — cases were recorded in meticulous, handwritten detail, and original documents can be found in libraries and archives worldwide — complete English translations are “few and far between,” says Melvin.

She knows of no single resource that offers all three: images, transcriptions, and translations. “We’re the only game in town.”

As the saying goes, necessity was the mother of this invention. Melvin, who teaches a Bates course on Inquisition, recalls comparing notes with a colleague at Boston College, Professor of History Sylvia Sellers-García, who also teaches the subject.

They both identified a “real shortage of English language material for students,” says Melvin. That led to a collaboration that produced Reading the Spanish Inquisition. “It came directly out of teaching needs, to make more material available for students.”

The website’s initial set of images, transcriptions, and translations are drawn from Mexican Inquisition papers preserved at the Huntington Library in San Marino, Calif. Meanwhile, the site’s functionality, look, and feel was developed by the “talented and patient folks” in two Bates offices within the college’s Information and Library Services devision, says Melvin: Curricular and Research Computing, and Systems Development and Integration.

Doing the initial transcription and translations were Melvin, Sellers-García, and others, including one of Melvin’s former students, Cristopher Hernandez Sifontes ’18. The process is “very labor intensive,” she says. “We manually do the transcriptions, and manually do the translations.”

Going forward, Melvin hopes the site can crowdsource transcriptions and translations from historians, and the site is set up to welcome guest editors.

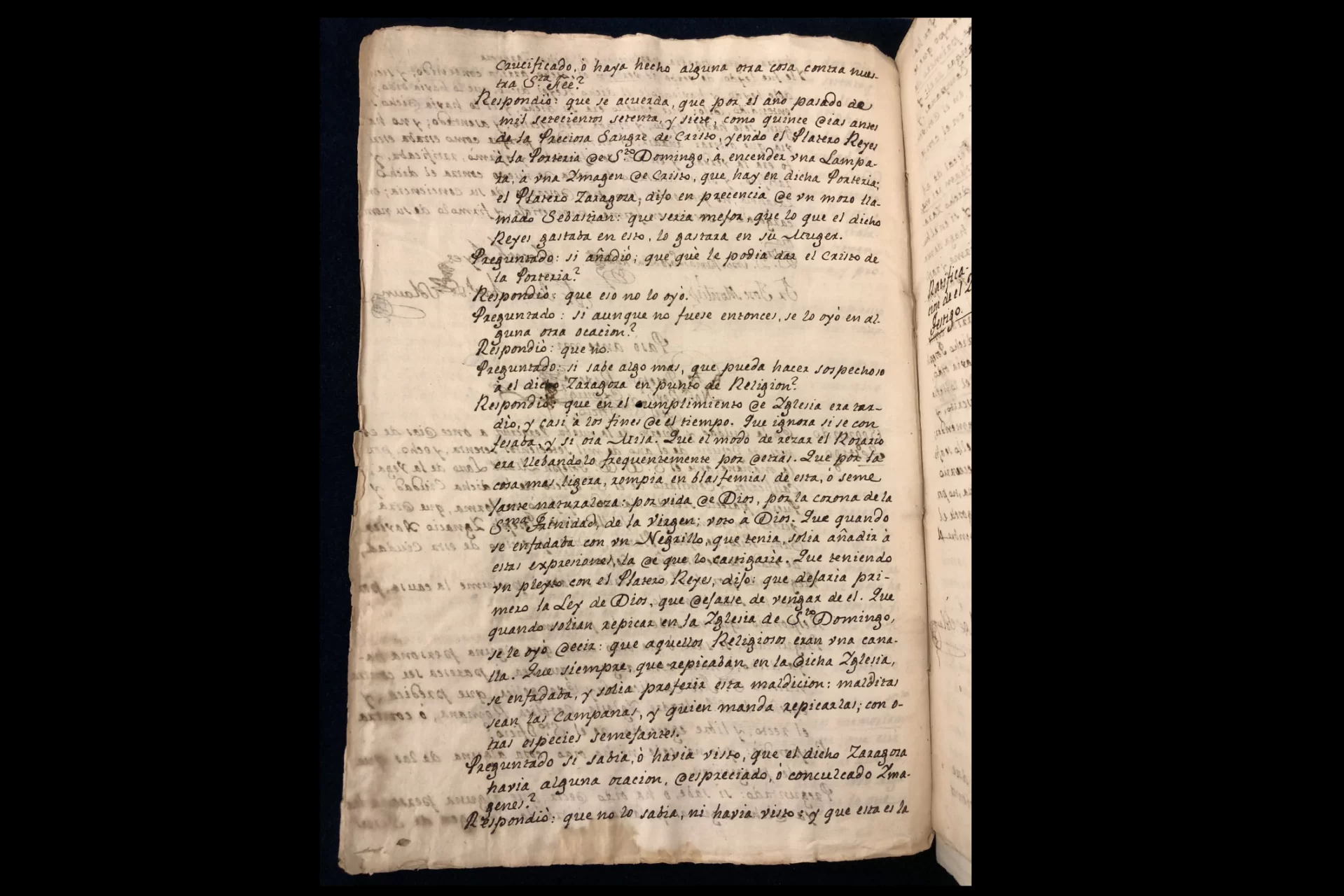

Through the case of accused silversmith Don Miguel de Zaragoza, readers can learn fascinating details of daily life in 18th-century Mexico that hint at the all-encompassing, sometimes fanatical nature of the Inquisition in Spanish society. Even for those who don’t read Spanish, the document images are compelling: the various Inquisition officials’ signatures are written with a great flourish, known as a rubric.

In Mexico as elsewhere in the Spanish Empire, the tribunal that carried out inquisitions had a few key figures. Zaragoza’s case was typical. It was heard by the local “commissary,” like a commissioner, in Veracruz. A “fiscal” prosecuted the case. Everything was recorded — written down, that is — by a notary.

After hearing the deathbed confession, the priest immediately took it to the local inquisitor.

Three witnesses called to testify against the silversmith, who apparently was not a well-liked man, nor particularly handsome. He had an “ill-kempt beard,” “an average mouth with a few teeth missing,” and “a high-pitched voice, with evidence of a carbuncle on his forehead that is still healing.”

It was said that Zaragoza “does not fulfill his Easter Duty” and that “over the slightest matter he would burst out in blasphemies” and “is so foul-mouthed that many consider him a Freemason.” (Even the suspicion of Freemasonry was potentially a capital offence during the Spanish Inquisition.)

Another said that Zaragoza “prays with his hands behind him so that the Rosary falls over his posterior, and he stands this way until completing it.”

Another, a fellow silversmith said that when the bells of the local church rang, Zaragoza would let out a curse: “Damn the bells and whoever has them rung!” The witness said that Zaragoza called friars “rogues” who “take the habit in order to assure themselves of a meal.” And Zaragoza would tease the silversmith, telling the man he should spend more time with his wife than worshipping Jesus.

All in all, besides wearing shoes with saints on them, Zaragoza was accused of “blasphemies, disparagement of pious acts, cult, and veneration of the image of Our Lord Jesus Christ Crucified.”

The silversmith was lucky. On Oct. 22, 1778, the fiscal recommended suspending the trial, ruling that “there are not sufficient merits to pursue this case until more proof is presented.” (The trial record doesn’t say what Zaragaza said in his defense, or if he was interrogated, though one witness testified that Zaragoza said the images were Prussian.)

Melvin has reason to be optimistic that scholars will contribute to the site. As she notes, regardless of whether a historian specializes in the Inquisition (Melvin’s own current research looks at alms collection networks in the early modern Catholic world), it’s not uncommon for historians “to have a case or two in their teaching arsenal,” she says.

That’s because, for teachers, Inquisition cases are “problematically rich.” That’s a good thing for students, who can learn about a treasure trove of complex topics with enduring historical relevance: religion, gender, anti-Semitism, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status, among others.

In popular culture, the Spanish Inquisition has proven also to be comedically rich. Exactly 50 years ago, Michael Palin kicked off a now-famous Monty Python skit with the line, “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!”

And though Python plays the Inquisition for laughs (the skit’s inept inquisitors torture a woman with soft cushions), our contemporary understanding of the Inquisition is pretty much how Palin’s Cardinal Ximénez clumsily states it: all about “fear, surprise, ruthless efficiency, an almost fanatical devotion to the pope, and nice red uniforms.”

“We try to address the Inquisition stereotype in the class,” says Melvin, because it “goes against a lot of recent scholarship. For example, there were only three tribunals in all of the Spanish Americas, in Mexico City, Lima, and Cartagena, and how active they were varied.”

Early in her course, Melvin does mention the Python skit to her students. “Some have heard of it,” she says. “Some think it’s funny — it’s not unknown.”