What do you get when you mix together one Bates biochemistry class, two teachers passionate about community education, and 120 middle schoolers? In the case of Assistant Professor of Biology Lori Banks’ latest project, a recipe for success.

Banks had just received a prestigious national grant to support her community outreach. Students in her cellular biochemistry course would be taking a deep dive into vitamins and human health. What if she paired her class with a local middle school, turning her Bates students into teachers?

As the school year opened last fall, one teacher at Lewiston Middle School, Nicole Goyette, was already planning to teach nutrition science in class, so she and Banks came up with a plan: Banks’ students would create video presentations for LMS students about the important role a nutritional, balanced diet plays in a healthy life, and then deliver ingredients for them to take home and make a meal that connected to the lesson.

They say too many cooks spoil the broth, but the most important ingredient in making this academic recipe collaborative and engaging for the middle schoolers was involving them directly in the project.

Six groups of LMS students — around 120 in all — collected and submitted recipes to Goyette. Then, throwing civics into the mix, they held a vote to decide what meal they would all be learning how to make.

For the middle-school students, each recipe needed to fit a few criteria.

“They first started learning about the different human body systems,” Goyette said. “Then we went into the different vitamins and what can happen if they have a lack of a certain vitamin, and what system that would affect.

“Then they researched where we find these vitamins, and in what foods, and that’s what led to this. They had to find a recipe that would give them at least three of the essential vitamins that they need in their daily diet.”

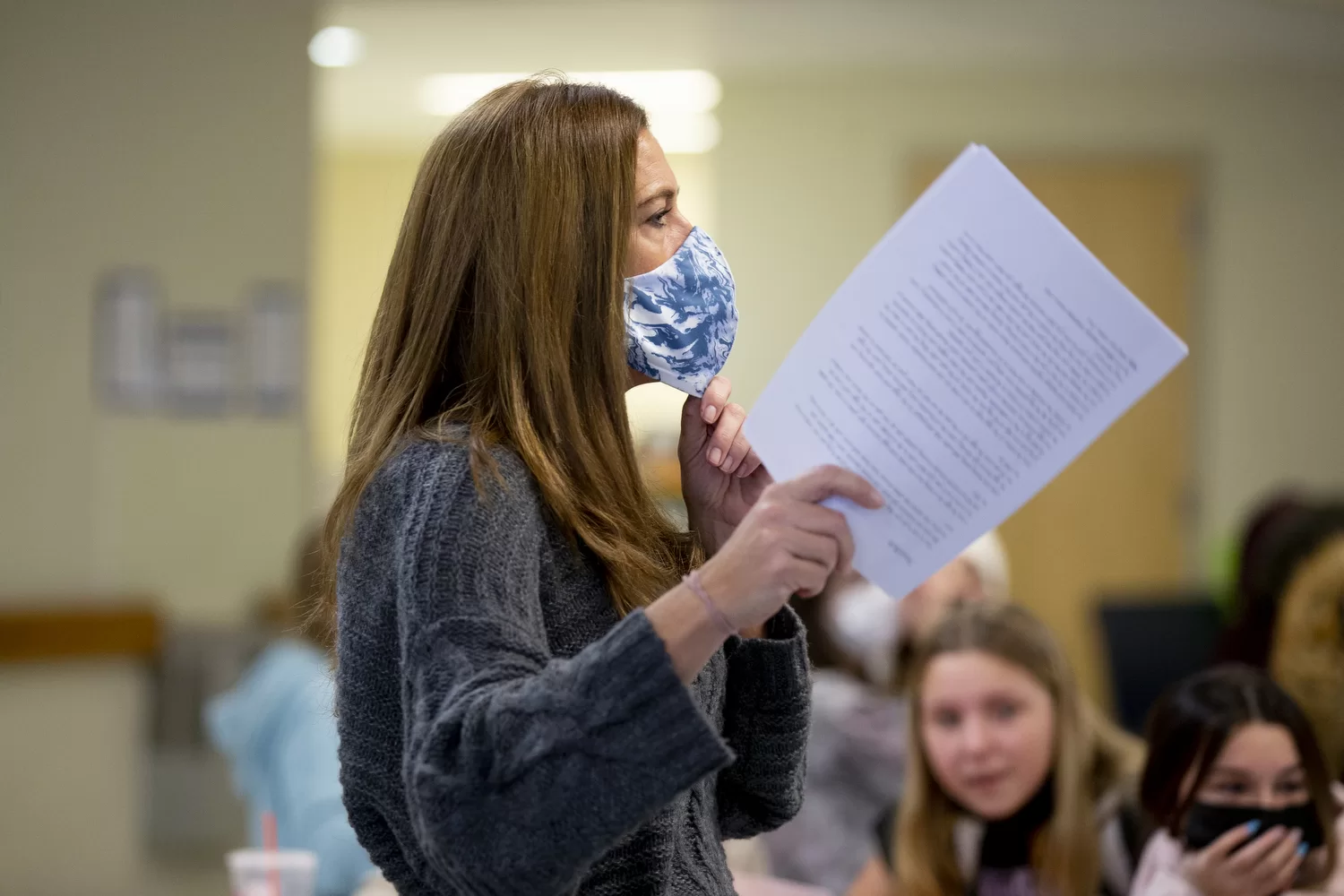

Students collected over 100 recipes for breakfast and dinner dishes, and narrowed them down to 12 for a final vote, held in the school cafeteria the day before Thanksgiving break. Before the vote, the students talked excitedly with each other and compared the recipes that had been chosen.

“They really wanted to win,” Goyette said. “That did help them really pay attention to what they were doing and to make it a recipe people would want to eat. That was the big thing here: which class is going to win?”

There was also a strong sense of ownership over the recipes, especially among students who had submitted similar recipes. When the winning recipe was announced, a huge cheer went up as they celebrated.

The recipe that won? A vitamin-rich veggie omelet, with cheese, mushrooms, tomatoes, and onions. Other recipes included everything from smoothie bowls and stir fry to West African dishes, including fufu, a dough-like food made from cassava.

“The middle school students have such agency in this process, because they are coming up with the recipe. What’s better than that?”

Banks wanted her students to not only learn about the science behind nutrition, but also the social effects of it, including access to and education about nutritional food.

“Not only are my students learning biochemical pathways but also some of the civic or real-world implications of what happens when somebody decides to build a liquor store instead of a Whole Foods, depending on what the neighborhood is,” Banks said.

“The middle school students have such agency in this process, because they are coming up with the recipe. They have to know what foods have lots of vitamin D, and what’s going to be delicious to them, and they can think, ‘I can do this in a way that fits my palate, and that is going to help me make good decisions so that I can treat my body well.’ What’s better than that?”

+Recipe: Veggie Omelet

Total time: 15-20 minutes

Veggie topping:

½ tablespoon butter

2 tablespoons onion, chopped

¼ cup mushrooms, chopped

½ cup fresh spinach

3 cherry tomatoes, halved

Shredded cheese to taste

Omelet:

2 eggs

2 tablespoons vegetable or canola oil

2 tablespoons water or milk

Salt and pepper to taste

- In a small frying pan over medium heat, melt the butter. Add the chopped onions and mushrooms and saute until the onions are transparent. Add the spinach and tomatoes. When the spinach is wilted, remove the pan from the heat and cover with a lid or foil to keep warm.

- Into a mixing bowl, crack the eggs. Whisk until the eggs are light yellow in color. Set aside.

- In an 8-inch nonstick frying pan over medium-low heat, pour the vegetable oil and swirl until the pan is evenly coated.

- While the oil is heating, add the water or milk, salt, and pepper to the egg mixture. Beat the mixture vigorously until it becomes light and airy.

- When the oil appears shimmery and hot, slowly pour in the egg mixture. Let it sit and bubble until the bottom of the mixture begins to set.

- Using a heat-resistant rubber spatula, gently push one edge of the omelet into the center of the pan, while tilting the pan to allow the mixture to fill in the space.

- Repeat with the other edges until there is no liquid mixture left. The omelet should resemble a yellow pancake and slide easily in the pan.

- Using the spatula and tilting the pan as needed, gently flip the omelet over and cook for a few more seconds. Do not overcook: the omelet should be soft and flexible, not stiff and brown.

- In the center of the omelet, spoon on the veggie toppings in a line. Sprinkle your preferred amount of cheese over the toppings. Fold both sides of the omelet over the toppings and let the cheese melt. Move the finished omelet to a plate.

The ingredients were supplied by Banks and funded by the Harward Center and from Banks’ national grant.

Sam Boss, the assistant director of community-engaged learning and research at the Harward Center, wanted to make sure most of the groceries were locally sourced, so he bought eggs, spinach, mushrooms, and onions for the omelet from Valley View Farm in Auburn. Then, thanks to a truck provided by a local Sherwin-Williams, they delivered everything to the school.

Biology major Eloise Botka ’23 of Cambridge, Mass., and her group made their video using a whiteboard, dry-erase markers, and narration. She was excited to be creating a learning tool.

“We really tried to focus on how to make middle-schoolers really want to watch the video,” Botka said. “Thinking back to when I was in middle school, if someone told me that a bunch of college students near me made a science video, it would have been pretty weird.

“My group definitely talked about how to make it something that they actually would want to watch and pay attention to.”

Even with COVID distancing rules, Banks wanted her students to be able to engage with the community around Bates, in a sustainable way — not just giving the middle-schoolers something temporary, but helping them learn skills and knowledge they can continue to use — and maybe a new favorite food.

The teachers at LMS are also getting something they can continue to use: the videos will be uploaded to BatesConnect, an online repository of teaching tools Bates students have created.

Through the videos, Banks’ students got a chance to transform what they were learning in the classroom into a tool that will have lasting value to the community.

“Science doesn’t just exist in my laboratory,” said Banks, whose lab in Bonney Science Center seeks to understand how key structural features of selected microbial proteins can be exploited in the design of new antimicrobial agents. “Science is everywhere. Whether it’s mathematical modeling, or whether it’s physics in a pressure cooker in somebody’s kitchen.”

Banks wants students to see that science can be done by anyone, anywhere, and cooking with family can be a great way for kids to learn about everyday chemistry.

“My first biochemistry professor was my Grandma,” Banks said. “She had the ratios of fat, carbohydrates, and water down to a science in the way that she made her pie crust. She could get it right every single time by making observations and thinking about how humid it was one day, or dry the next. But the outcome was exactly the same every single time.”

Banks’ pedagogical approach is inspired by favorite figures of educational entertainment: The Magic School Bus’ Ms. Frizzle, Bill Nye the Science Guy, and everyone’s friendly neighbor, Mister Rogers. All these programs teach important social, scientific and scholastic concepts while being entertaining, well-researched, and approachable for children.

Named one of 1,000 inspiring Black scientists in 2020 by the web resource Cell Mentor, Banks has long sought ways to bring science into her communities and schools.

In 2017, as a post-doc at Baylor College of Medicine, she and others joined a March for Science, whose activities included a strawberry DNA extraction exercise — held on the lawn of Houston City Hall and joined by 300-plus visitors and other science presenters.”

The opportunity to redesign her cellular biochemistry course to focus on community engagement came in 2021, when Banks was named a Periclean Faculty Leader, a national honor that provides funding to college professors who “create and teach innovative courses” that “champion civic engagement.”

As shown by the partnership with Lewiston Middle School, Banks’ redesigned course now asks hard questions about public health, with attention to race and inequality, and how marginalized populations in the U.S. are disproportionately affected by illnesses related to vitamin deficiency.

“What are the real health outcomes that happen as a result of people not being able to have access to produce or fresh, farm-raised animal products?” Banks asked. “If they are created in a way that makes them nutritionally deficient, then you lose a lot of these cofactors, and what are the clinical implications of that on a person-by-person basis?”

As the Lewiston youngsters become high schoolers, and as the Bates students become alumni, there’s a strong chance that no one involved in this project, from Batesies who delivered the eggs to the middle-schoolers who cracked them, will ever forget the lesson — that nutrition is important in building a healthy community — behind a simple omelet.