Like many children, young Estellita loved to collect butterflies. And she had a wonderful place for the pursuit: her grandparents’ Pennsylvania farm, where she spent much of her childhood in the 1940s. But unlike most children, Estellita had someone who could teach her about the butterflies she collected: her grandmother, the remarkable Bates graduate Stella James Sims, Class of 1897.

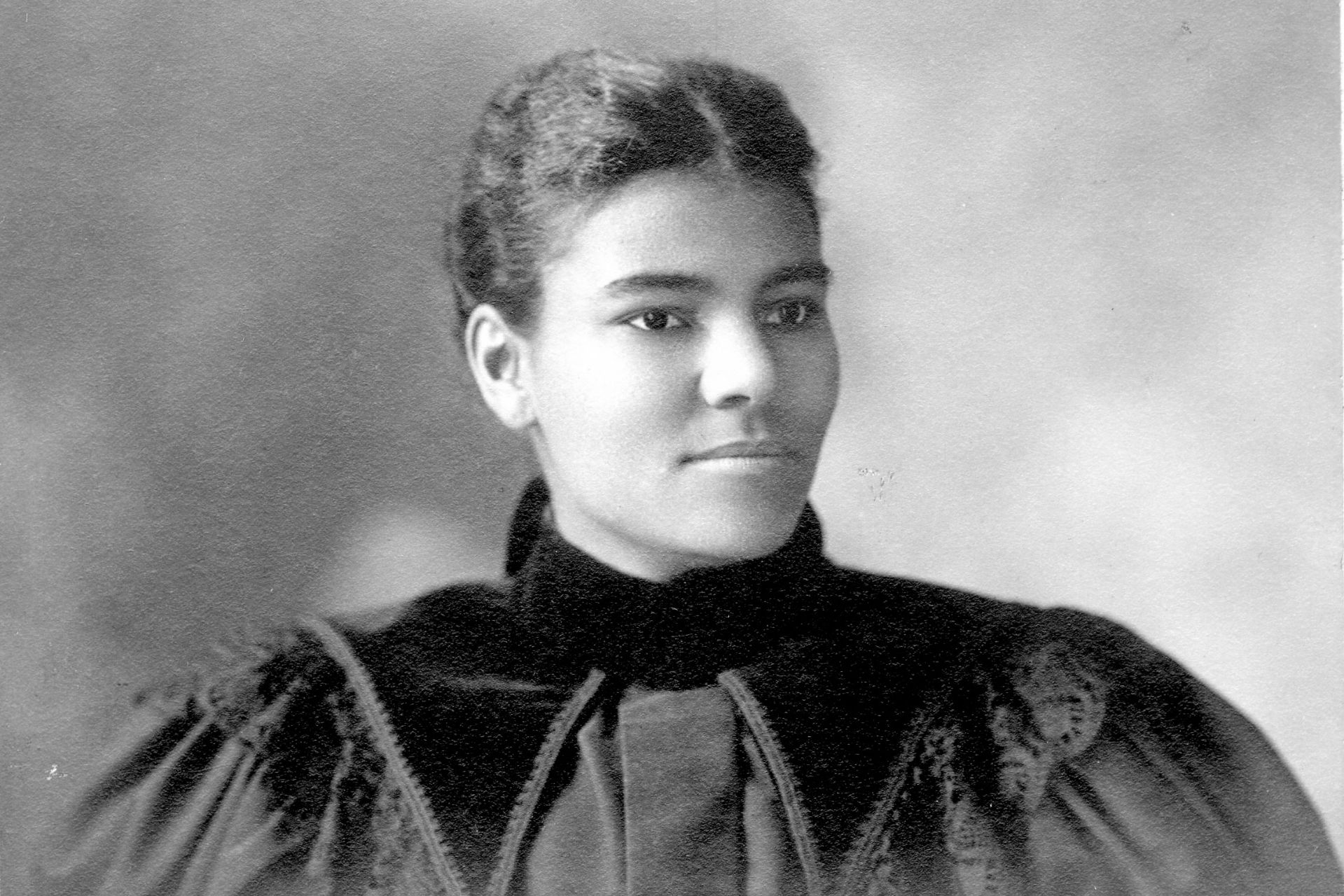

A Black woman who traveled from West Virginia to Maine to attend Bates — becoming the college’s first female Black graduate — Stella James Sims was a career science educator who, in the early 1900s, deepened the reputation of a historically Black college in West Virginia as a leading teachers college.

In addition to teaching a range of science courses and serving as dean of women during her 28-year career at Bluefield State College, James Sims was the wife of the Bluefield president, helping her husband bring notable Black leaders to campus, all while raising five children. She was also an officer in the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools.

She is remembered as a science teacher who inspired others to follow her path as a teacher. “I can remember how her love of biology came out,” recalled her granddaughter, Estellita Gonzales Rainwater-August, for a Bates oral history in 2006. “I can remember her taking the time to take out the books and tell me what the butterflies all were and how they evolved.”

Stella’s Champions

Longtime Bates dean James Reese and Professor of Physics John Smedley have long been interested in the life of Stella James Sims. Their investigations and efforts over the years, including conducting an oral history interview with Sims’ granddaughter in 2006 which is now in the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library, have uncovered many of the details included in this story.

Stella James Sims’ name and legacy have a new prominence at Bates these days with the appointment of Paula Schlax as the inaugural Stella James Sims Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry.

In August, speaking to a small gathering held in the Schlax lab in Bonney Science Center, following a ribbon-cutting to open the building, Dean of the Faculty Malcolm Hill explained that the Sims professorship “honors a faculty member whose contributions to biochemistry, accomplishments as a pedagogue, achievements as a researcher, and effectiveness as a leader have enriched STEM at Bates and the college as a whole.”

Before Stella Sims traveled north to Bates, in 1893, she did college preparatory studies at Storer College, a historically Black school, now closed, located in Harpers Ferry, W.Va. Linking the two schools was Bates founder and Freewill Baptist leader Oren Cheney. In 1867, Cheney encouraged Maine philanthropist John Storer to make a $10,000 gift that enabled an erstwhile Harpers Ferry primary school to evolve into a college to train much-needed Black teachers.

At Bates, James took courses in mathematics, botany, ornithology, physics, chemistry, astronomy, and geology. She received second honors in physics, earning a spot to speak at her Commencement, on July 1, 1897. Considering that only 390 Black students had earned a college degree from a predominantly white U.S. college by 1900, according to W.E.B. Dubois, James’ achievement, of a Southern Black woman receiving a science degree from a Northern, white-founded college, is distinctive, if not unique.

By graduation, James’ abilities as a public communicator were already established, as evidenced by essays in The Bates Student marked by precision and boldly practical thinking. In one essay, she wrote of the manifold significance of Harpers Ferry. This geological wonder, she wrote, is a Gibraltar-like formation “lying somewhere between the present and the past.” She refers to John Brown’s historic 1859 uprising there, intended to bring on abolition — “the first blow against slavery, and at Charlestown its first martyr was tried and hung.”

In another Bates Student essay, “Manual Training,” Sims brilliantly anticipated the tension between vocational and college-prep education at the secondary level. “Shall the manual laborers finish a preparatory collegiate course — for the public and fitting schools tend toward this end — and then begin the training of their life work?” she asked.

By “manual training,” Sims did not mean “digging ditches, hodding brick, washing, and the like.” Instead, she was thinking about skilled, hands-on work, which “is not, [and] neither can be, independent of intellectual training, although we try to draw a line between manual and intellectual labor.”

She argued that scientists like James Watt and Isaac Newton called on their manual and mechanical skills, their practical ways of knowing the world, as much as their intellectual heft to make their discoveries. She reasoned that infusing manual labor into school curricula strengthened intellectual development by “cultivating exactness, keenness of observation, and bringing us in contact with the practical and concrete, rather than the theoretical and abstract.”

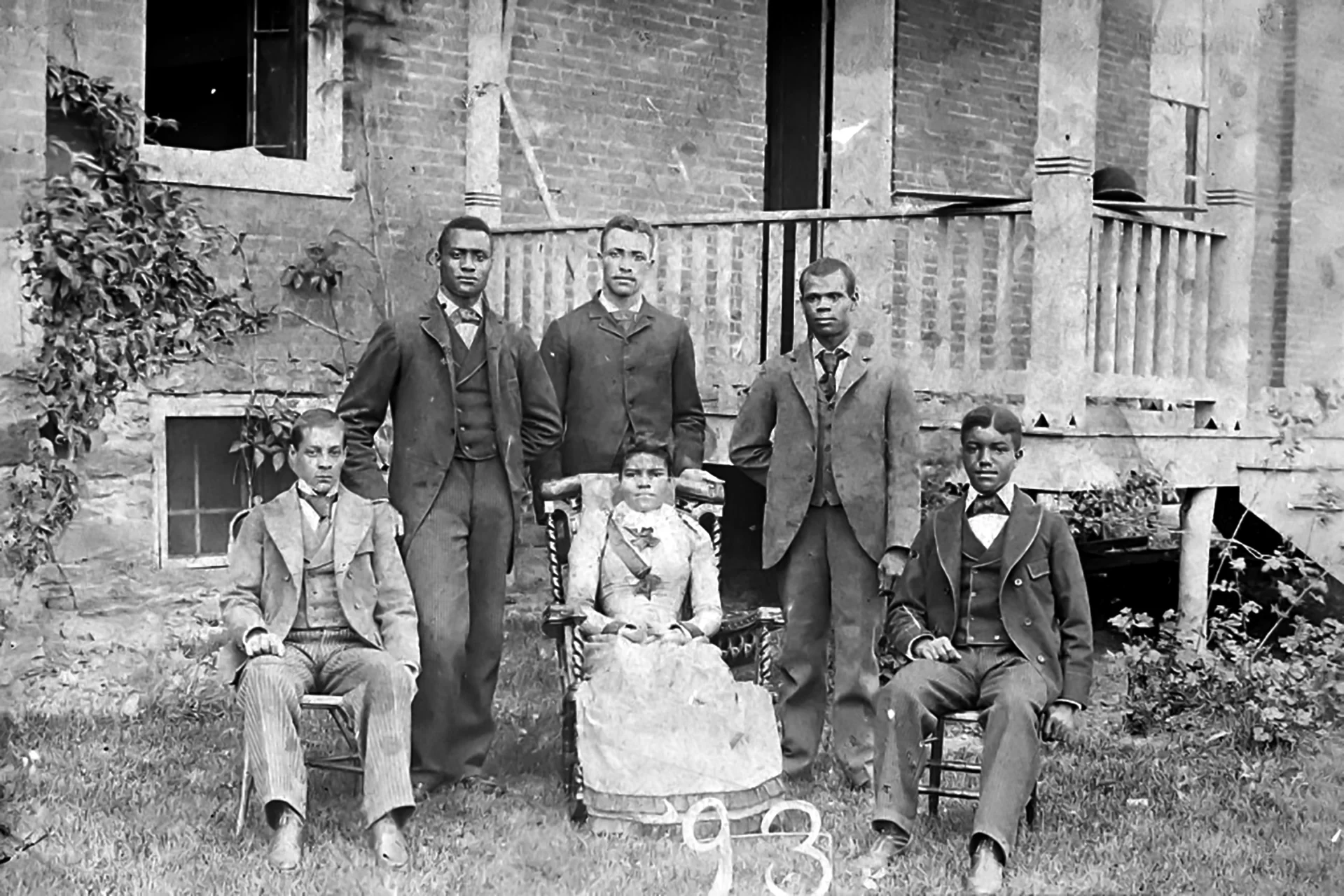

Upon graduating from Bates, James returned to the South. She taught science and physics at Virginia Seminary, now Virginia University of Lynchburg, and at Storer. In 1901, she married a fellow Storer graduate, Robert P. Sims, who had earned his degree at Michigan’s Hillsdale College, which, like Bates, had been founded by Freewill Baptists. They had known each other for years at that point: A photograph of Stella at Storer in 1893 shows Robert Sims standing behind her.

Perhaps reflecting ideas about education that Stella James Sims articulated while at Bates, Bluefield emphasized both vocational and academic coursework.

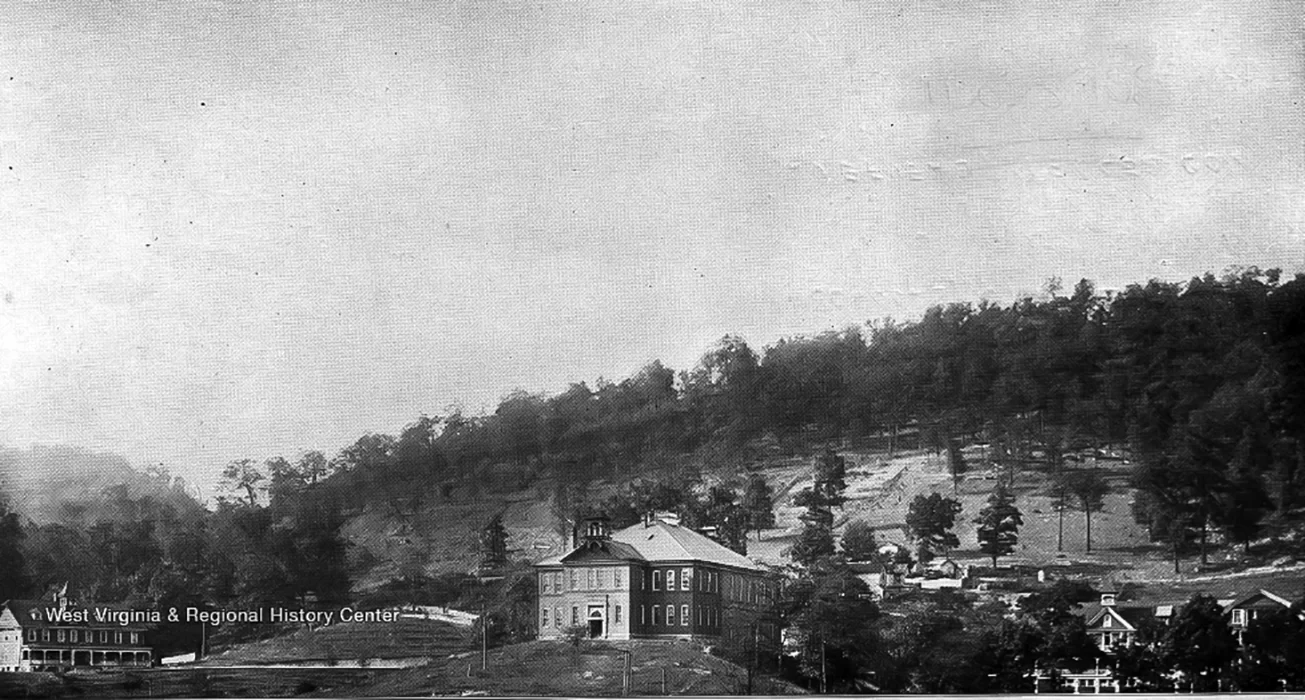

In 1906, she joined the faculty at what was then called Bluefield Colored Institute, where Robert had been appointed president, a school founded to educate children of Black coal miners in the region, and had by then evolved into a school to educate teachers. (Yet another marker of the Storer–Bates connection is the fact that Robert Sims’ predecessor at Bluefield was Hamilton Hatter, Bates Class of 1888, who taught at Storer before becoming Bluefield’s first president.)

The Bluefield setting was beautiful, a10-acre campus 2,700 feet above sea level at the base of the Stoney Ridge Mountain. About half the campus was used for growing fruits: apples, cherries, peaches, grapes, raspberries, and strawberries. “All the work of tree planing, fruit culture, and vegetable production is performed by the students under the watchful eye of the principal.”

Perhaps reflecting ideas about practical education that James Sims had articulated while at Bates, Bluefield emphasized both vocational and academic coursework.

“In addition to the regular courses of study usually pursued in a school of this character, we are aiming to give special attention to the manual arts and certain kinds of handicraft,” noted a report to the state by the Bluefield board of trustees in 1907. The goal of a Bluefield education, they said, was to prepare Black students “to become part of that higher citizenship for which the state strives, and that they may be a part of that intellectual life which should keep pace with the material development of the state.”

At Bluefield, James Sims taught a range of biology, botany, and zoology courses. In keeping with her Bates writings, she encouraged her students to conduct hands-on fieldwork. Her stated goals included “awakening an interest in the pupil for nature and its workings.”

Already well known for its teacher-education curriculum, Bluefield was expanding in size in the early 1900s, adding 22 acres and a new classroom building, and in scope, adding offerings in business administration, home economics, and education. “Prof. and Mrs. Sims…are really building an institution that will occupy a large place in the educational and social well being of the community,” reported the local newspaper, The Daily Telegraph, in August 1925.

By 1931, the school was renamed Bluefield State Teachers College. “Much of the success of the entire program [at Bluefield] was due to the teaching personnel,” wrote Charles Ambeler in A History of Education in West Virginia from Early Colonial Times to 1949. And “among the most effective teachers,” he wrote, was James Sims.

Various sources indicate that Robert Sims, no doubt aided and abetted by Stella, worked to bring leading figures in Black culture to campus, helping Bluefield to achieve “recognition as a center of African American culture,” according to New Life for Historically Black Colleges and Universities.

W.E.B. Dubois twice spoke at Bluefield, including a 1927 visit, where he gave addresses on “Negro Art and Literature” and “Russia.” In 1930, Marian Anderson sang at the downtown Granada Theater. The record shows that James Sims kept up with changes in the teaching profession. As an officer for the West Virginia chapter of the National Association of Teachers in Colored Schools, James Sims contributed an article to the association’s publication, The Bulletin, discussing the role of the parent as the focus of childhood education moved from the home to public schools.

She and Robert Sims retired to their farm in Perkiomenville, Pa., in 1934; he died in 1944. And Bluefield State College? It’s still classified as a historically Black college, though its enrollment is now 86 percent white.

James Reese, the longtime Bates dean, has a deeply held interest in the life of Stella James Sims. (As has Professor of Physics John Smedley, whose investigations have uncovered many details included in this story.)

Reese once visited Harpers Ferry to learn more about her life. There, he met one of Sims’ former students, then in her 90s, who vividly recalled “Miss Sims.” The woman, learning that her former teacher went to Bates, said, “Oh, well, that must be why her standards were so high.” She lived to be 88. Her grave is in Harpers Ferry, that spot she described as “lying somewhere between the present and the past.” At Bates, her name is now tied to the future of scientific study