One day, the little girl announced to her kindergarten teacher, “I want to be an entomologist!” While her classmates dreamed of becoming princesses, dragons, and firefighters, Essie Martin ’22 already knew what she wanted to do: study the natural world.

Martin was raised in the coastal Maine town of Damariscotta. As she grew up, so grew her love of the ocean and her community, as well as her understanding of how coastal communities depend on the marine economy.

“Since a young age, I’ve always wanted to sort of work with oceans and help oceans,” she says.

But at the same time, she’s also had a front-row seat to the effects of climate change. “I’ve seen climate change in action in a way that I wouldn’t have otherwise if I had grown up somewhere else,” she says.

“There’s the side of me that really hopes that kelp is contributing to climate mitigation and the oceans can be a solution to all this, and then there’s the science hat that I put on in the lab.”

At Bates, Martin is putting her advocacy into informed action. She’s majoring in geology and minoring in chemistry, and her senior honors thesis is studying the ability of kelp to sequester carbon, a popular rallying point of climate activists encouraging investment in ocean health.

Kelp absorbs carbon from the atmosphere through photosynthesis, and then sinks to the ocean floor like leaves in a forest, eventually becoming part of the ocean floor, holding onto the captured carbon for — hopefully — millions of years.

“There’s a lot of media hype about kelp and its ability to sequester carbon, but actually there’s very little scientific evidence to back that up,” says Martin.

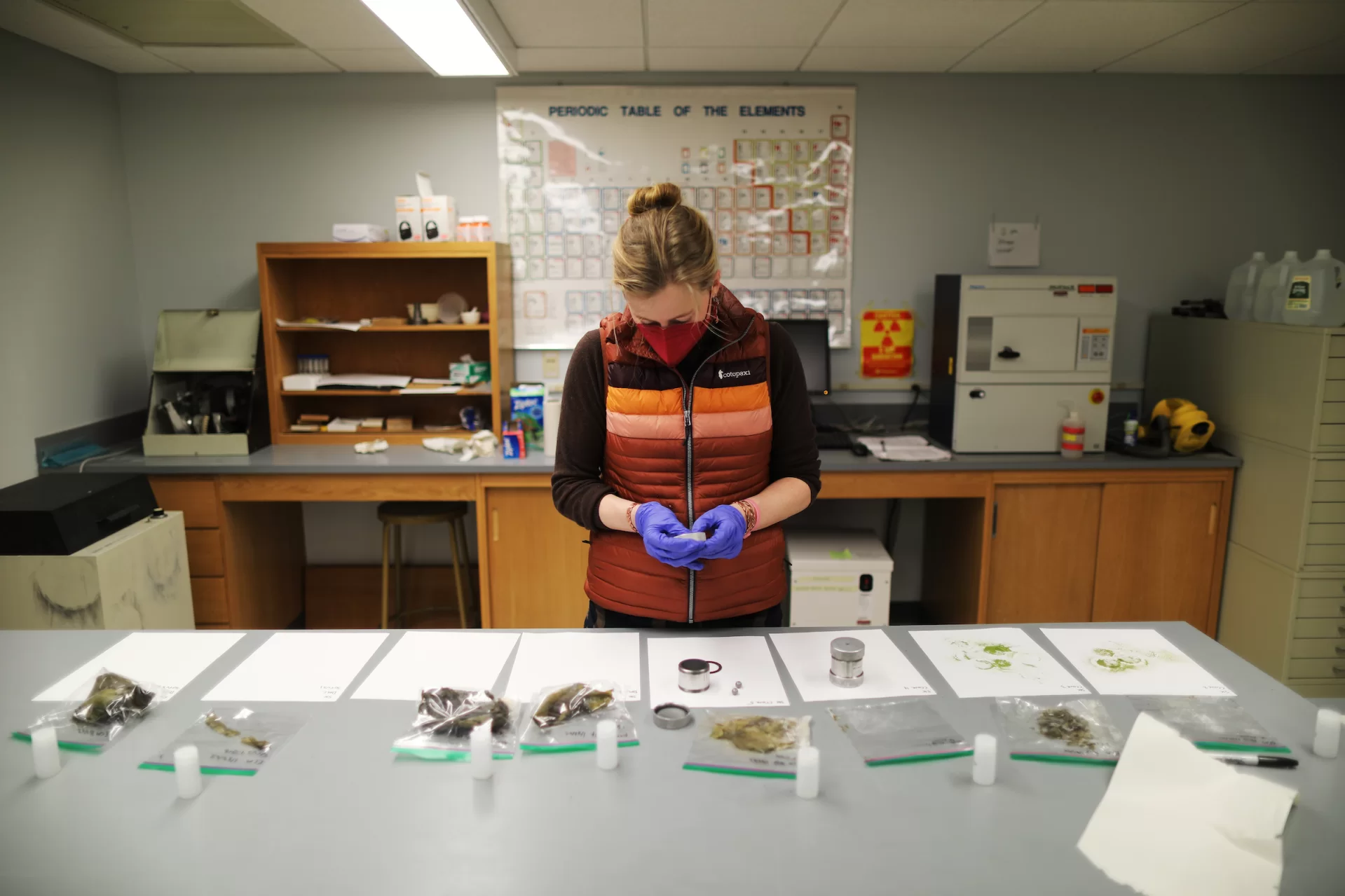

By collecting sediment samples from the sediment below seaweed farms located on the coastal Damariscotta River and studying them in the lab, Martin can see if there’s any presence of environmental DNA or carbon isotopes in the sediment, which could indicate carbon sequestration.

To identify carbon and nitrogen isotopes, Martin uses a stable isotope ratio mass spectrometer in the Environmental Geochemistry Laboratory at Bates. For the eDNA analysis, she was able to access new and important eDNA technology being developed at Maine’s internationally known Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences by senior research scientist Nichole Price. In the Price lab, doctoral student Sam Tan is helping to analyze Martin’s samples.

Martin explains that her honors thesis is part of a “preliminary study to just see if there’s kelp in the sediment at all. After that, there’s going to be a lot more work that needs to be done. And that could be a future project for me in grad school or beyond.”

“There’s a lot of media hype about kelp and its ability to sequester carbon, but actually there’s very little scientific evidence to back that up.”

For Martin, “grad school or beyond” will receive funding from a highly competitive Harry S. Truman Scholarship, which will help her pursue a master’s degree in aquaculture and policy. Martin hopes to follow that with a doctorate in geochemical oceanography.

The Truman Scholarship recognizes individuals who show leadership potential and are committed to public service, traditionally defined by land-locked efforts around social justice. With climate change knocking on earth’s door, Martin appreciates that “an important element of public service now is our oceans and our fisheries and aquaculture.”

Martin’s fieldwork has been through internships with the University of Maine’s Darling Marine Center, in Walpole, Maine, where she’s studied kelp and oyster farms.

“I found that my favorite part of the job were days when I got to go out on the farm and either helped do some of the work or drive the boats around. I just love getting my hands dirty with it,” says Martin.

“I have always been the muddiest kid on the playground and my mom used to get really upset at me for it. My coworkers still make fun of me today. I’ll come back to the lab and I’ll just be drenched in mud head to toe.”

But getting her hands deep in mud and seaweed is one of the things that makes her the happiest, even if it’s cold.

“I’ll come back to the lab and I’ll just be drenched in mud head to toe.”

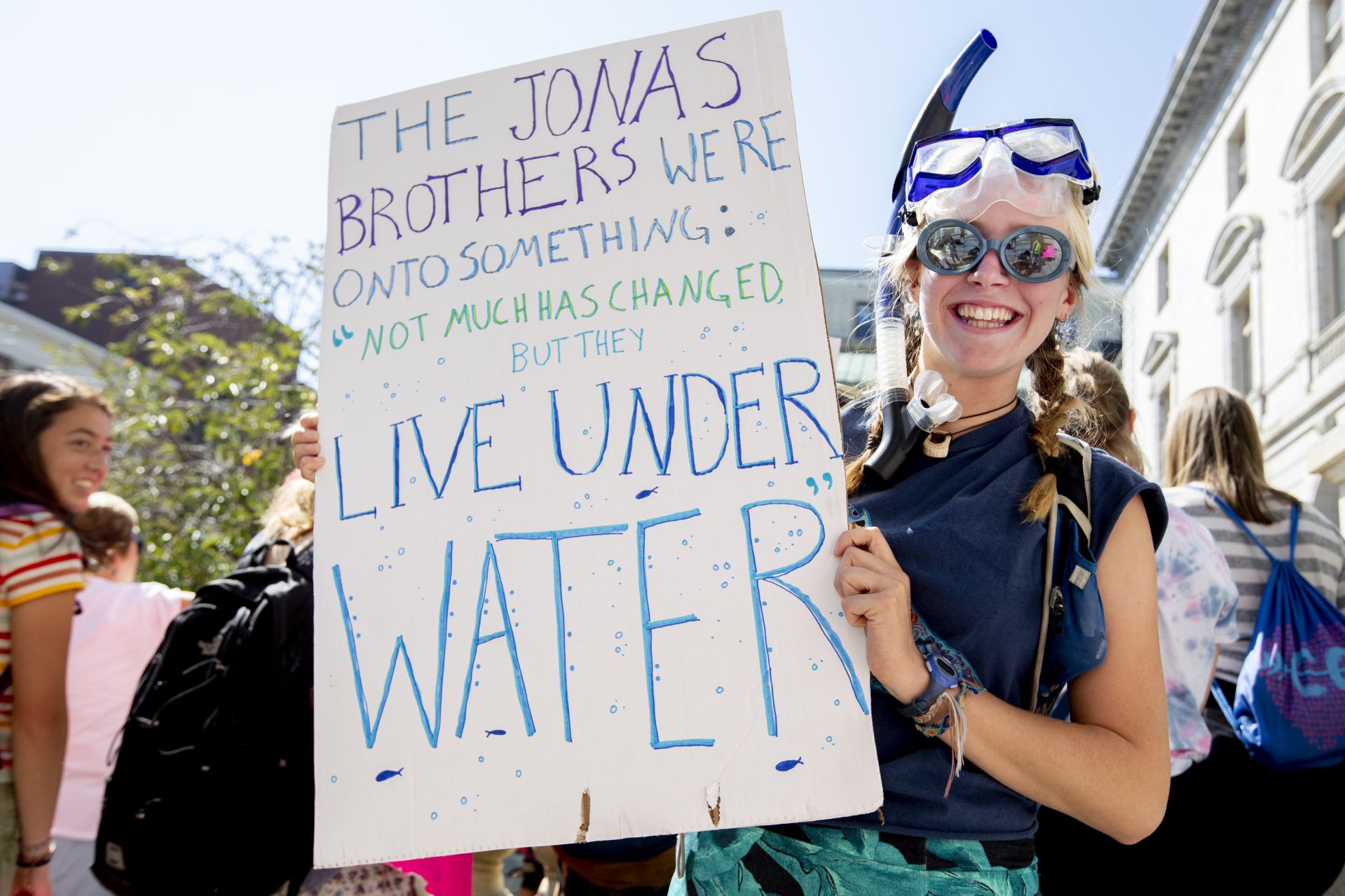

During her time at Bates, Martin’s approach to environmental advocacy has matured. From simple ideas like pulling plastics from the ocean to finding long-term sustainable ways to utilize existing aquaculture resources, she’s figuring out how to be a scientist-activist.

“I feel like I’ve had to create two hats for myself,” says Martin. “There’s the side of me that really hopes that kelp is contributing to climate mitigation and the oceans can be a solution and all this, and then there’s the science hat that I put on in the lab.”

When she’s in the lab, Martin puts the science hat on. “I just plug my music in and I do the lab work. I don’t really think about the intention when I’m in the lab.”

It’s not easy, she says. “I know that this is something that a lot of scientists go through learning, and I’m still very much in that process. Working through those emotions is really important.”

Help and guidance comes from mentors like Martin’s thesis advisor, Professor of Earth and Climate Sciences Bev Johnson, and the Darling Marine Center’s Damien Brady.

Alternating between the lab and the field showed Martin the push-and-pull of aquaculture academics and industry, and she wants to foster that partnership, especially since a large part of the economic life of the Maine coast is drawn from the ocean.

“In Maine, there’s traditionally been sort of some bad blood between industry — particularly the lobstering industry and scientists — because there’s this idea that science is always regulating the lobster industry, which is true,” she says. “I would like to be a scientist who is informing that policy and looking at how to — particularly with aquaculture, because it’s such a new industry — keep it green, and keep it sustainable as a long-term industry.”