“What happens when we are deprived of the ability to grieve?”

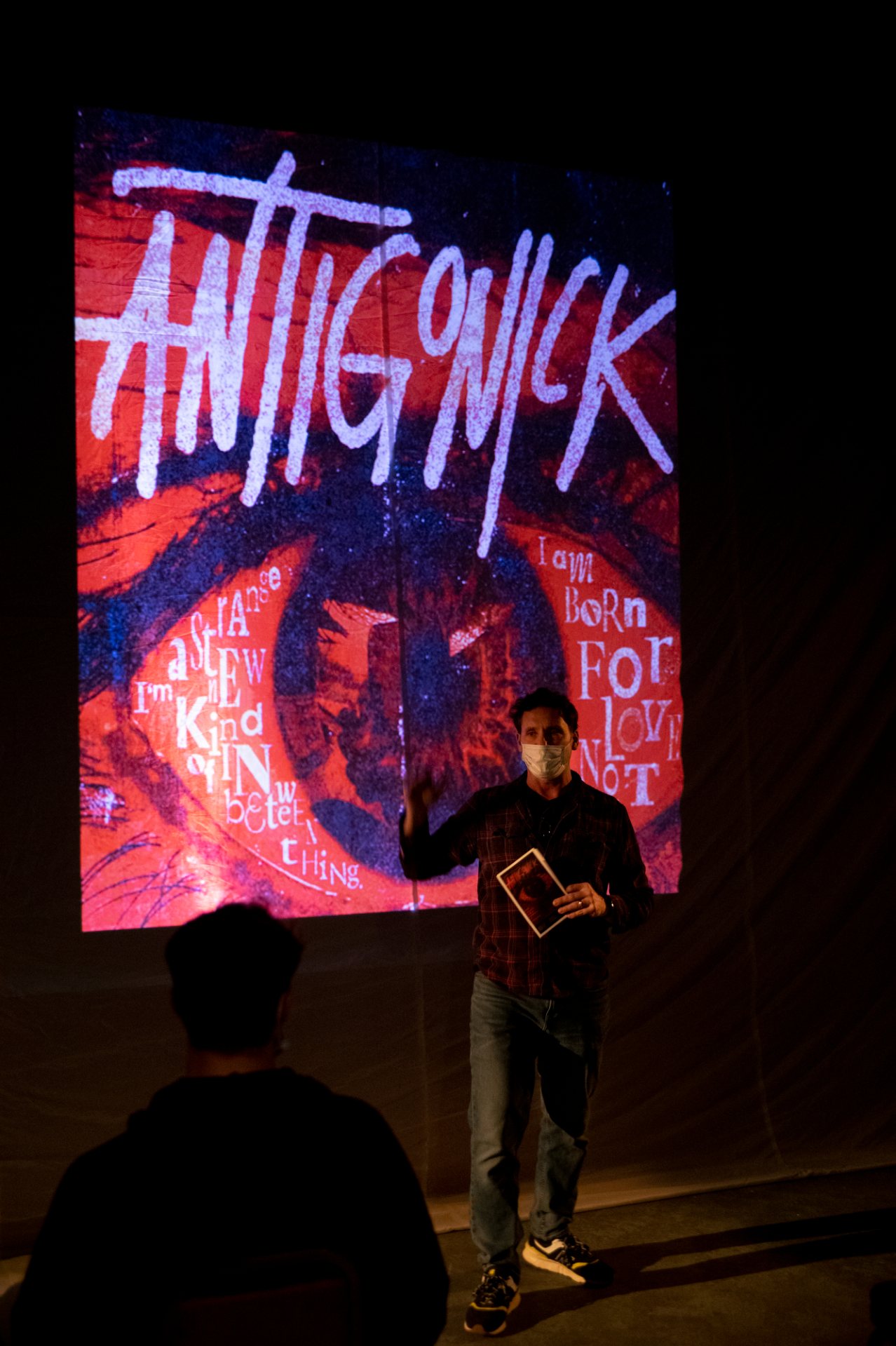

That’s the question the cast and crew of Antigonick, now in a sold-out run at Schaeffer Theatre, asked in January as they set out to stage their adaptation of poet Anne Carson’s innovative translation of Sophocles’ play Antigone.

In case you need a brief refresher of Sophocles and Greek mythology, Antigone, the daughter of Oedipus, has been deprived of the ability to grieve. She’s trying to secure a decent burial for her brother Polyneikes; he was killed by their other brother, Eteokles, when the pair fought on opposite sides of the the war of the Seven against Thebes.

Their uncle is Kreon, whose son Haimon is in love with Antigone; she’s determined to bury Polyneikes’ body, but in doing so, is condemned to death by Kreon because he considers Polyneikes traitorous.

In addition to making meta-references and pulling back the curtain on more silent characters, Carson’s adaptation adds the character of Nick, who silently measures things throughout the play.

Staging Antigonick at Bates has offered an “idyllic opportunity” to dig deep into Anne Carson’s text, says director and Assistant Professor of Theater Tim Dugan, and to devise theatrical elements to support the story through puppetry and shadow theater. It’s also idyllic to be producing theater as pandemic restrictions have eased.

“To be a part of this process and of making theater once again in person has filled me with such gratitude.”

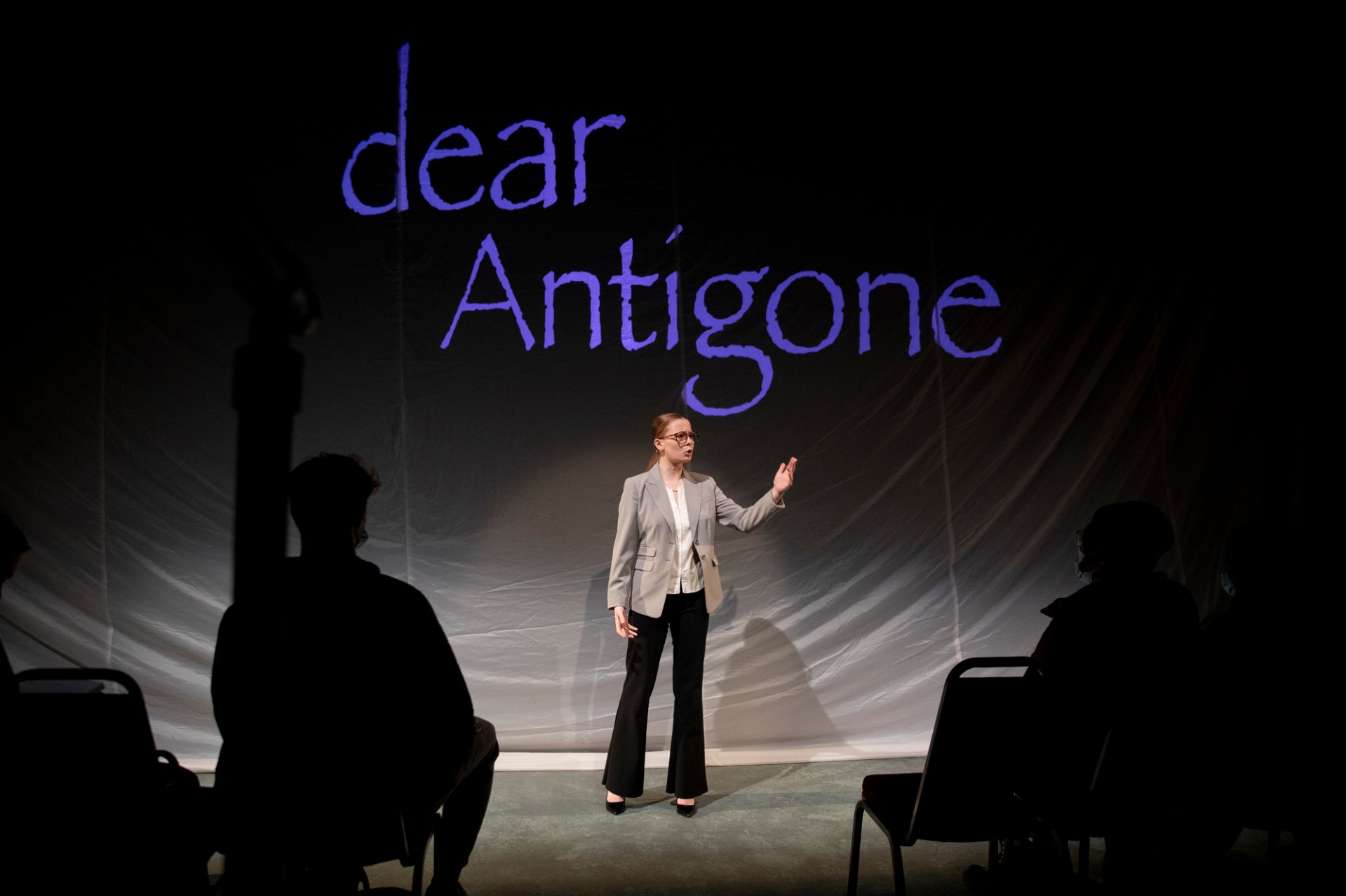

The task of the Translator

Sydney Childs ’24 of Cohasset, Mass., is the Translator, delivering Anne Carson’s opening letter to Antigone, referencing earlier translations and interpretations of Antigone’s narrative, and promising to forbid that she should ever lose her screams.

“Your name in Greek means something like ‘against birth,’ or ‘instead of being born.’ What is there, instead of being born?” The Translator asks Antigone at the beginning of the play.

“It is the role of the translator to give Antigone back her voice and her story; to shift from a story of broken men to the truth of women,” says dramaturg Maggie Nespole ’23 of Annapolis, Md.

Slain in shadows

The stage is set with a battle prior to Antigone’s story, as Polyneikes, above left, played by Miguel Pacheco Gonzalez ’24 of San José, Costa Rica, and Eteokles, above right, played by Manuel Machorro Gomez Pezuela ’25 of Mexico City. As one way to expand on the text, the shadow warfare is designed by John Farrell, artistic director and co-founder of Figures of Speech Theatre, which is affiliated with the Department of Theater and Dance.

Dancing chorus

One of two choruses ensembles in the play, this silent —and masked — chorus expresses their role through movement, choreographed by Carol Dilley, professor of dance.

From left, Joaquin Torres ’25 of Silang, Philippines, Jacob DiMartini ’22 of Harrington Park, N.J., Caroline Cassell ’24 of Woodstock, Vt., Quinn Simmons ’24 of Croton on Hudson, N.Y., and Sydney Childs ’24 dance in the shadows.

Family — and family, and family again

Antigone (left), played by Caroline Cassell ’24, and Ismene, played by Quinn Simmons ’24 are sisters — as well as aunt and niece — to each other, caught up in a twisted, deadly family tragedy.

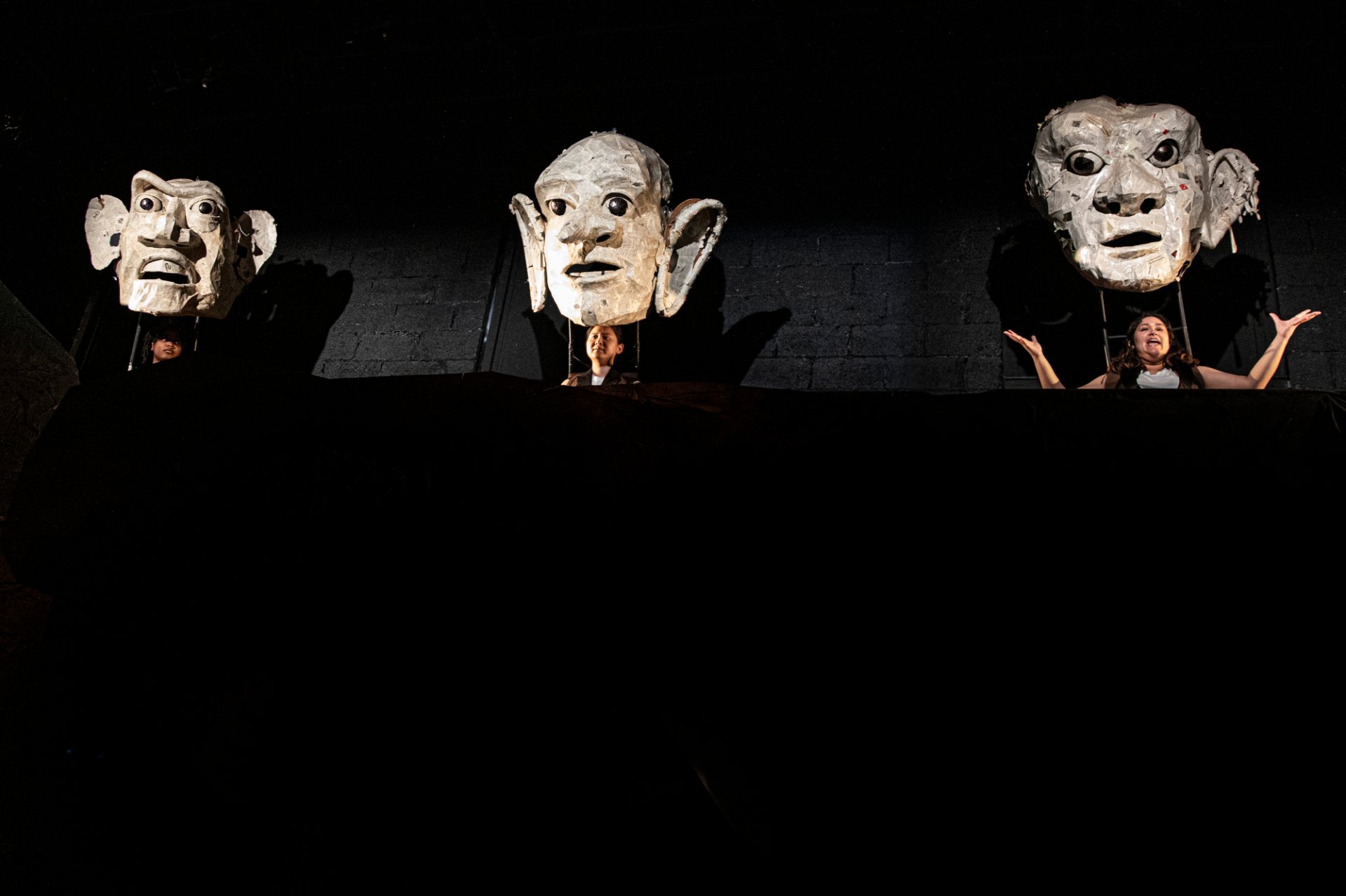

Commentary from the balcony

Dramaturg Maggie Nespole ’23 says there are “moments where the play steps out of its plot to become commentary; these are the moments that highlight Carson’s political statement. The moments that, perhaps, help us to listen and to better hear characters who are long since dead.”

From left, Bora Lugunda ’25 of Kinshasa, Congo, QinYing Zuo ’22 of Shanghai, and Ananya Rao ’25 of Bedford, N.H., manipulate and voice a puppet chorus of Old Theban Men, designed by John Farrell.

A guard against fate

Miguel Pacheco Gonzalez ’24 plays the Guard, a very different character from Haimon, and the costumes reflect that difference. Though the guard’s costume — designed by Carol Farrell — is buttoned all the way up, his movement onstage is anything but contained.

This is one of the many roles Gonzalez portrays throughout the show (Guard, Chorus Ensemble, Haimon, and Teiresias Puppeteer) and Farrell’s costume design “reveals this particular character brilliantly,” says Dugan.

Measure of a woman

“Nick is most likely the loudest mute character to be portrayed on stage,” says Nespole. “Carson’s take on this classic offers… an invitation to explore themes of female autonomy, voice, and how to be loud while in a position of silence.”

“It represents when Antigone starts to grapple with the reception and history of the play and her characterizations, and that Nick is part of her presence — he’s the one who measures her self-measuring. It sets up the following moment when Antigone feels Nick’s presence before they lock eyes for the first time,” says Dugan.

Father and son

As Haimon agonizes over his love for Antigone, his father, Kreon, played by Jacob DiMartini ’22 is desperate to find — and execute — whoever buried Polyneikes, even if it’s his own niece.

“Carson’s translation includes a general shift in Kreon’s voice that highlights a history of victim blaming, the mistrust of women, and the disregard for a woman’s autonomy,” says Nespole.

Another kind of sight

Joaquin Torres ’25 plays the Boy guiding Teiresias, and speaks for Teiresias, represented by one of John Farrell’s puppets and manipulated by Miguel Pacheco Gonzalez ’24.

Puppetry and theater are a perfect partnership in the character of Teiresias, the blind — but far-seeing — prophet.

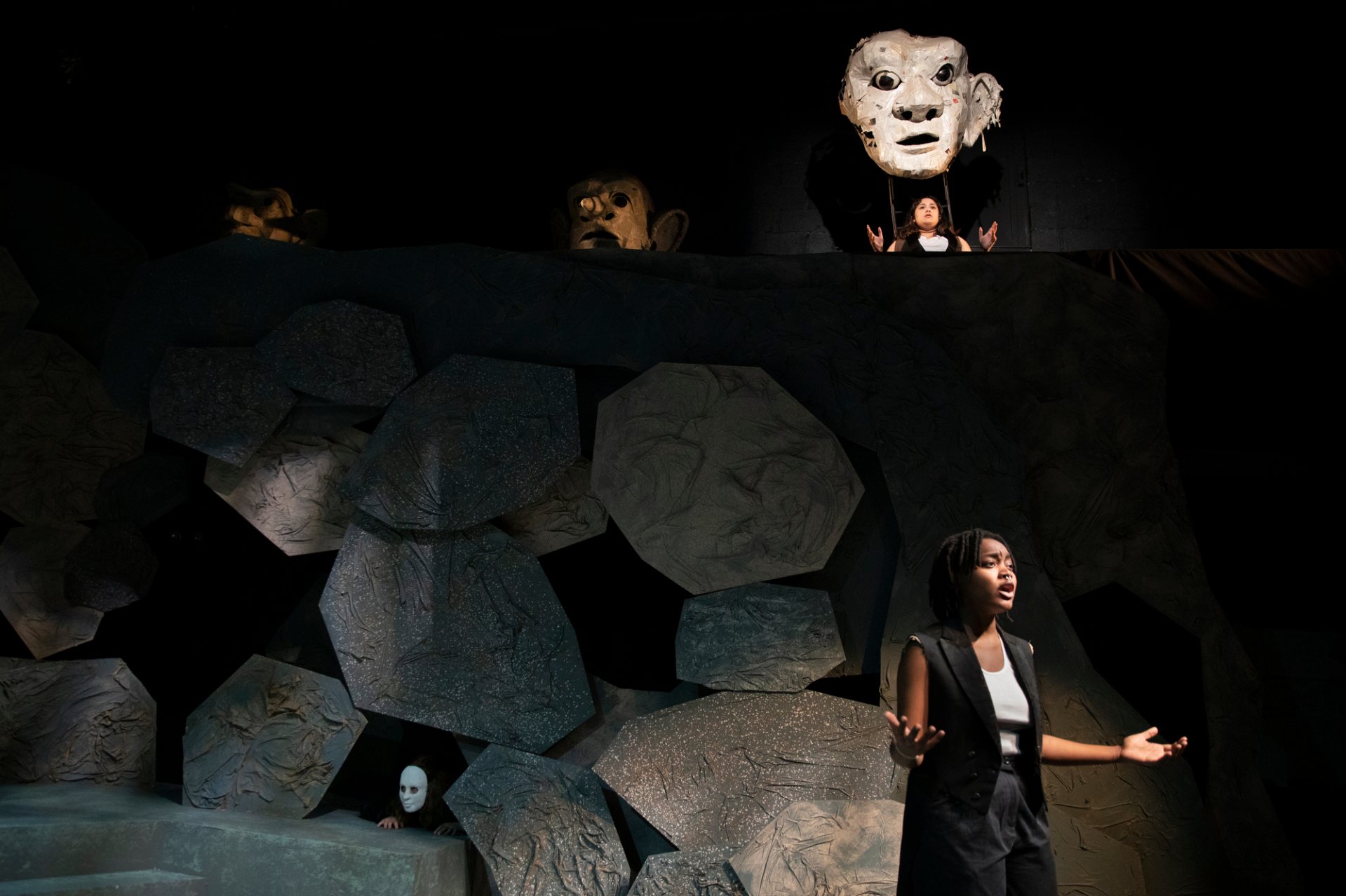

Between a rock and a hard place

With Nick waiting to measure, and a member of the chorus peeping from behind a rock at left, the Messenger, played by Manuel Machorro Gomez Pezuela ’25, delivers lines in front of the set designed by guest artist Marie Laster — the “subterranean world” of Antigonick.

Shedding some light

Light and shadows fall on members of the Theban chorus. Unmasked, Bora Lugunda ’25 is below, Ananya Rao ’25, still masked, watches from above.

As each member of the Theban chorus removes their puppet head, it “represents a transformation from the Chorus of Old Theban Men to the Chorus of Contemporary Identity, who cannot support what Kreon is doing to Antigone or what he stands for,” says Dugan.

(Almost) silent presence

Eurydike is Kreon’s wife, played by Sydney Childs ’24. She delivers only one monologue throughout the play, but nonetheless arrests the audience with her presence, her words, and her costume.

Shrouded in regret

Onstage, Kreon agonizes over the dead body of his son, Haimon, after Haimon chooses to commit suicide rather than keep fighting with his father over Antigone’s life.

“Playing Kreon has expanded me so much as an actor,” says Jacob DiMartini ’22. “The language in the show really allowed us all to explore.”

Fate marches on

Traditionally, Kreon has the “last moment of the last words” in Antigone, says Dugan.

In the Bates production, Antigone has the last say.

“This was something we devised together,” says Dugan. “In essence, it’s bringing her story back to the forefront of the audience’s awareness. It also lifts the last words of the play and serves as a wake up call to all of us: ‘last word / wisdom-better get some / even too late.'”