Since 2018, when the Bonney Science Center project was publicly announced, we’ve mostly talked about the center in the future tense.

What it will look like. What we hope will happen within its brick and glass walls when Bates professors, as both researchers and as teachers, take their ideas — and their students — across traditional disciplines of chemistry, biochemistry, biology, and neuroscience.

Well, now it gets real.

Since the building opened for the fall semester, Director of Photography and Video Phyllis Graber Jensen has made multiple visits to Bonney to engage with the building’s new residents as they, in turn, begin to engage with their new home.

“The architect has commissioned stunning photographs of what the building looks like,” Graber Jensen said. “I wanted to complement that, and portray in a candid way what life looks like for those who work in Bonney, day in and day out.”

Windows, lab benches, and chairs. Doors, stairs, and desks. Classroom multimedia, automated lighting, expansive views of campus — it’s all now in the hands of the Bates faculty and staff who work in Bonney, each of whom we will profile in images and words in the coming weeks.

Here are our first three: Colleen O’Loughlin, assistant professor of chemistry and biochemistry; David Hanscom, building custodian, and Mary Hughes, who oversees the vivarium.

Colleen O’Loughlin

Title: Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry

Joined Bates: 2018

Date Photographed: June 24, 2021

She says: “My office is here and everything for research is here — it’s awesome.”

For Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Colleen O’Loughlin and fellow faculty and staff who moved into Bonney Science Center last summer, the relatively quiet weeks of a Bates summer offered get-to-know-you time in Bates’ newest academic building.

For example, on the morning of June 24, O’Loughlin took time to explain to her student researchers some of the improved features of her laboratory space, including the fume hood.

“I explained to them that the hood that is big enough to hold all the solutions we need to stain and visualize biofilms,” she says.

In the life of bacteria, biofilms are helpful, serving as a kind of “apartment building, a structure that protect bacteria from external stresses, like antibiotics or the immune system, the same way that apartment buildings or houses protect us from the elements and weather outside,” O’Loughlin explains.

Continuing the metaphor, O’Loughlin and her student researchers are seeking ways to “alter the design of these apartment buildings, to see if we can design antibiotic drugs that might be able to get inside those apartment buildings” and help remove the bacteria.

“I’m in the building that I teach classes in. My office is here and everything for research is here — and it’s awesome.”

The fume hoods are important because the bright purple dye that researchers use to stain biofilms “requires a lot of fixing and rinsing and drying — honestly, it’s a bit like developing film,” says O’Loughlin. “The hoods in Bonney are much larger than the hood I had in Dana, and it makes this process a lot easier.”

The improved hood is just one example of how Bonney is giving faculty and students more of what no one has enough of: time.

“I used to have to go back and forth between Carnegie and Dana, and it was very difficult to fit in experiments between classes. Now I am in the building I teach classes in, my office is here, everything for research is here — and it’s awesome.”

Like many others who moved into Bonney Science Center last summer Assistant Professor of Chemistry and Biochemistry Colleen O’Loughlin has been struck, both literally and figuratively, by how much more natural light cascades into the building.

As she posed for a photograph in her office on one of the longest days of the year, June 24, she was thinking how she’d be able to “put many more plants in here over the years” than she could in her old digs in Dana Chemistry Hall.

David Hanscom

Title: Custodian with Facility Services

Joined Bates: 2020

Dates Photographed: Feb. 2 and Feb. 23, 2022

He says: “Just trying to keep up with it.”

Frequent freeze-thaw cycles this past winter left a stubborn layer of ice on campus walkways. That meant lots of sand had to be put down for safety — and that spelled more work for campus custodial staff, including Dave Hanscom.

“A lot of foot traffic brings in a lot of sand,” says Hanscom as he wields his trusty Windsor Sensor XP12 commercial vacuum cleaner. “In the winter, the bag will fill up in just two days.”

He was working in one of the first-floor Bonney classrooms when the photo was taken. He was thinking, “I’m just trying to keep up with it.” Hanscom has a wry sense of humor. “I guess the only way to stop the sand is to cancel classes,” he says with a smile.

The last time Bates created an entirely new science building, Dana Chemistry Hall in 1965, the primary surfaces were hard and hardy: brick, concrete, plastic, and linoleum.

In Bonney Science Center, Hanscom has a few more surfaces to tend to, including natural wood, which he cleans with Murphy’s multi-wood cleaning spray, which has 99% naturally derived ingredients and is 100% biodegradable. Then there are the carpets and fabric-covered chairs. Stains in those come out with Delta Ultra cleaner and degreaser.

“Seeing the students working in the labs. That’s cool.”

(In recent years, the college has reduced the number of everyday cleaning products menu from 15 to four, all of which meet the EPA’s Design for Environment Standard for Safer Cleaning Products.)

In this photo, he’s using Murphy’s to wipe down one of the large study tables in the main lounge area. “I’m thinking of my next task in that room — it’s a pretty big area,” he says.

An intentional design feature is lots of glass, from the huge curtain walls that look out onto campus to the many interior glass walls that give good glimpses of what’s going on in the labs. All that glass “looks more intimidating to clean than it is,” he says. Still, “I’m always looking for smudges.”

Perhaps the most fun piece of custodial equipment is the Tomcat Sport V2.0 walk-behind floor scrubber. “It’s like using a snowblower,” Hanscom says. “It does all the work.”

Hanscom came to Bates after working for 18 years at a nearby assisted living center. Going from a quieter, elderly community to a more youthful one took some adjustment. But now, that’s the best part of the work: “Seeing the students working in the labs. That’s cool.”

Mary Hughes

Title: Vivarium Coordinator

Joined Bates: 2001

Dates Photographed: Feb. 8, 2022

She says: “You’re going to be bad before you’re good.”

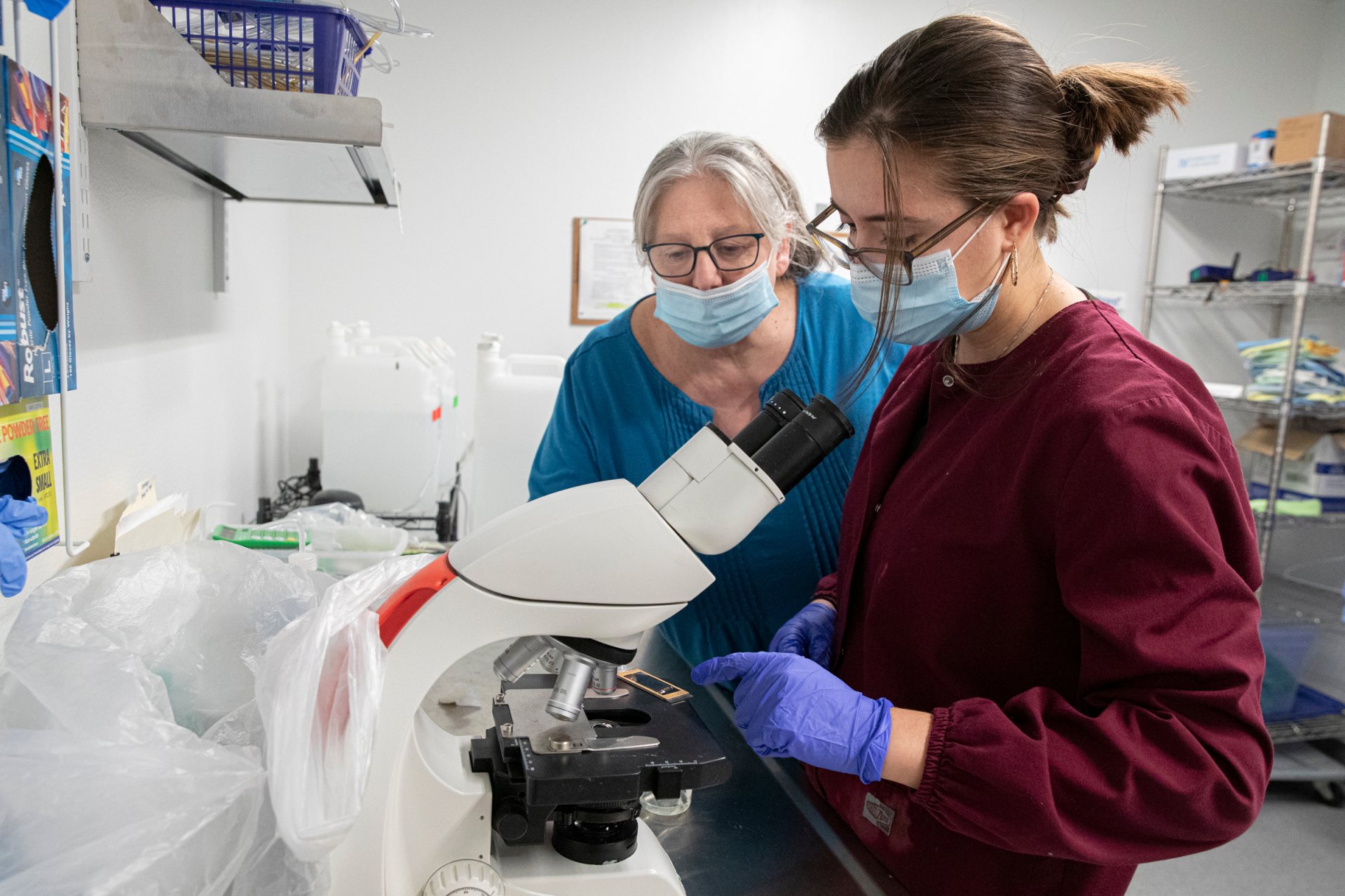

Mary Hughes watches intently as Emily Walsh ’24 of Sausalito, Calif., learns how to count “rotifers” under a microscope.

Rotifers are tiny microscopic invertebrates that, among other attributes, are food for the larval zebrafish that Hughes and her student workers grow in the vivarium.

A powerful model organism in biological research, zebrafish have helped scientists develop therapies for muscular dystrophy; better understand certain cancers, including mesothelioma; and, in a Bates lab, research how toxicants affect the development of aquatic species.

In the vivarium, rotifers are cultured in buckets filled with salt water and a rich amount of nutritious algae, then fed to the larval zebrafish. While it’s easy to measure a cup of chow for a dog, it’s hard to measure out the correct number of rotifers at mealtime. (And like any creature, larval zebrafish must be fed a specific amount of rotifers.)

Walsh was learning how to take a small sample from the total serving of rotifers, place it under a microscope, and count the rotifers with a clicker.

From that count, a mathematical formula is used to extrapolate the total number of rotifers in the serving. From there, adjustments can be made to the serving’s “food density” before the rotifers become the fish larvae’s next meal.

One of Hughes’ new student workers, Walsh is just learning this complex process. As with learning any skill, getting good at rotifer counting is “about repetition,” says Hughes. And like any good teacher, she doesn’t expect her student workers to be adept right off the bat. “You’re going to be bad before you’re good,” she says.

Students have to learn how to manipulate a special counting slide, called Sedgewick-Rafter cell, which is not easy. At first, “you’re going to set it up wrong. You’re going to put the slide on wrong. You put the cover slip on wrong. It just takes practice.”

“I love to see them gain the confidence they need, and tell me, ‘I got this!’”

And while there’s only one way to execute the task, Hughes sees many reactions from students.

“Everyone’s different. Failing bothers some more than others — they want to get it right the first time. But I always warn them: ‘You’re not gonna get this the first time. And it’s okay if you break a slide If you don’t get the count correct the first time, it’s okay. It’s like algebra: you’re not gonna get it right the first time.”

And working with students and teaching them a skill? “The best part of my job,” she says. “I love to see them gain the confidence they need, and tell me, ‘I got this!’”