On an April weekend in 1919, Bates junior Benjamin Mays and some college friends walked downtown to see a movie at a Main Street theater. When the movie was over, they sprinted back to campus, fearing for their safety. It all had to do with the film they saw, The Birth of a Nation.

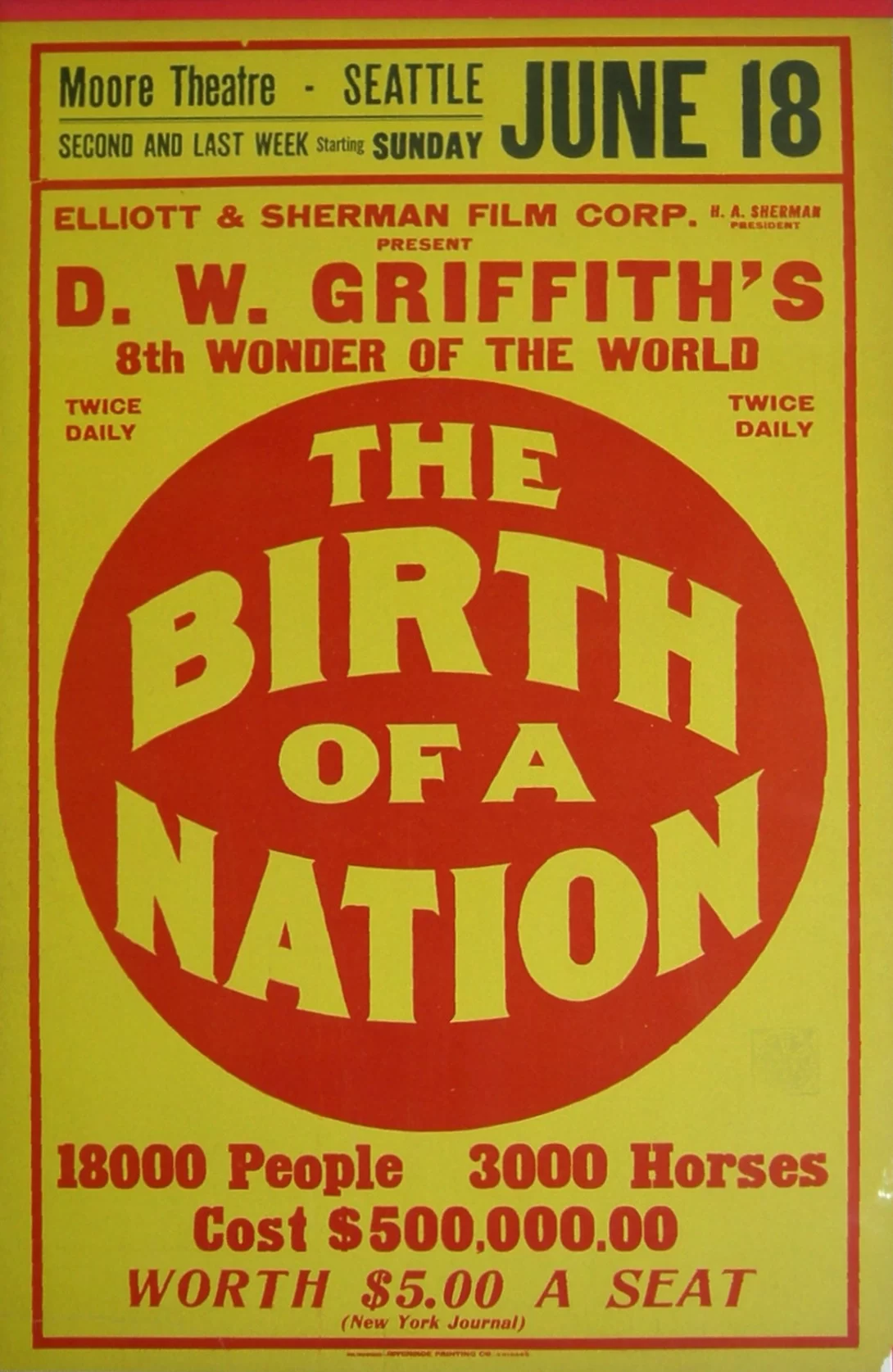

When it premiered, in 1915, it was a tour de force, featuring filmmaking wizardry that audiences had never before seen. For a comparison, “Star Wars would be a close analogy,” says Charles Nero, the Benjamin Mays Distinguished Professor of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies, who specializes in film, literary, and cultural studies at Bates.

The movie’s special effects were mind-boggling, especially the Civil War battle scenes, “which were epic, something that cinema had not seen before,” Nero says. Throughout the movie, director D.W. Griffith employed new storytelling tactics, including flashbacks, closeups, and panoramic filming.

But in contrast to the way a good-vs.-evil film like Star Wars uses filmic tactics to reinforce audience sympathy for the good, The Birth of a Nation was all about reinforcing and celebrating evil: white supremacy and racism against Black Americans.

“It taught white people that ‘Black people were horrible,’” Nero says. The late critic Roger Ebert emphasized that The Birth of a Nation “did more than any other work of art to dramatize and encourage racist attitudes in America.”

The plot of The Birth of a Nation intertwines stories about two families during and after the Civil War, one Northern and one Southern. The first part, featuring amazing battle scenes, is set during the Civil War; the second part is set during Reconstruction.

The Reconstruction segment features perhaps the film’s most infamous scene, where Gus, a freedman and soldier played by a white actor in blackface, wants to marry Flora, a young white Southern woman. She rejects his advances and flees into a forest. Gus gives chase.

Through the scene, D.W. Griffith uses innovative cinematic tactics that retain their power a century later.

Gus trips over a log, allowing Flora to get away from him — but then he closes the gap. While Gus chases Flora, her brother, a potential savior, tries to pick up the trail. Tight shots of Flora’s terror-stricken face complement wide shots of her weaving through the trees and Gus in pursuit.

“She’s going higher and higher, so you know that she’s probably going to get to the top and have to make a decision,” says Nero. “What’s going to happen? Your heart starts to race.”

Landmarks along the chase, such as a blown-down tree, help the viewer keep track of who’s where, heightening the sense of drama. Frequent cross cuts from Flora to Gus and back again build the suspense as he chases her up a rocky hill.

“She’s going higher and higher, so you know that she’s probably going to get to the top and have to make a decision,” says Nero. “What’s going to happen? Your heart starts to race.”

Up until that scene, Mays and his Bates friends may well have been drawn in and entertained by the movie. And Mays himself was probably feeling quite good. Not only was winter turning to spring — a reliable barometer of optimism on campus — but he was fresh off a debate team victory.

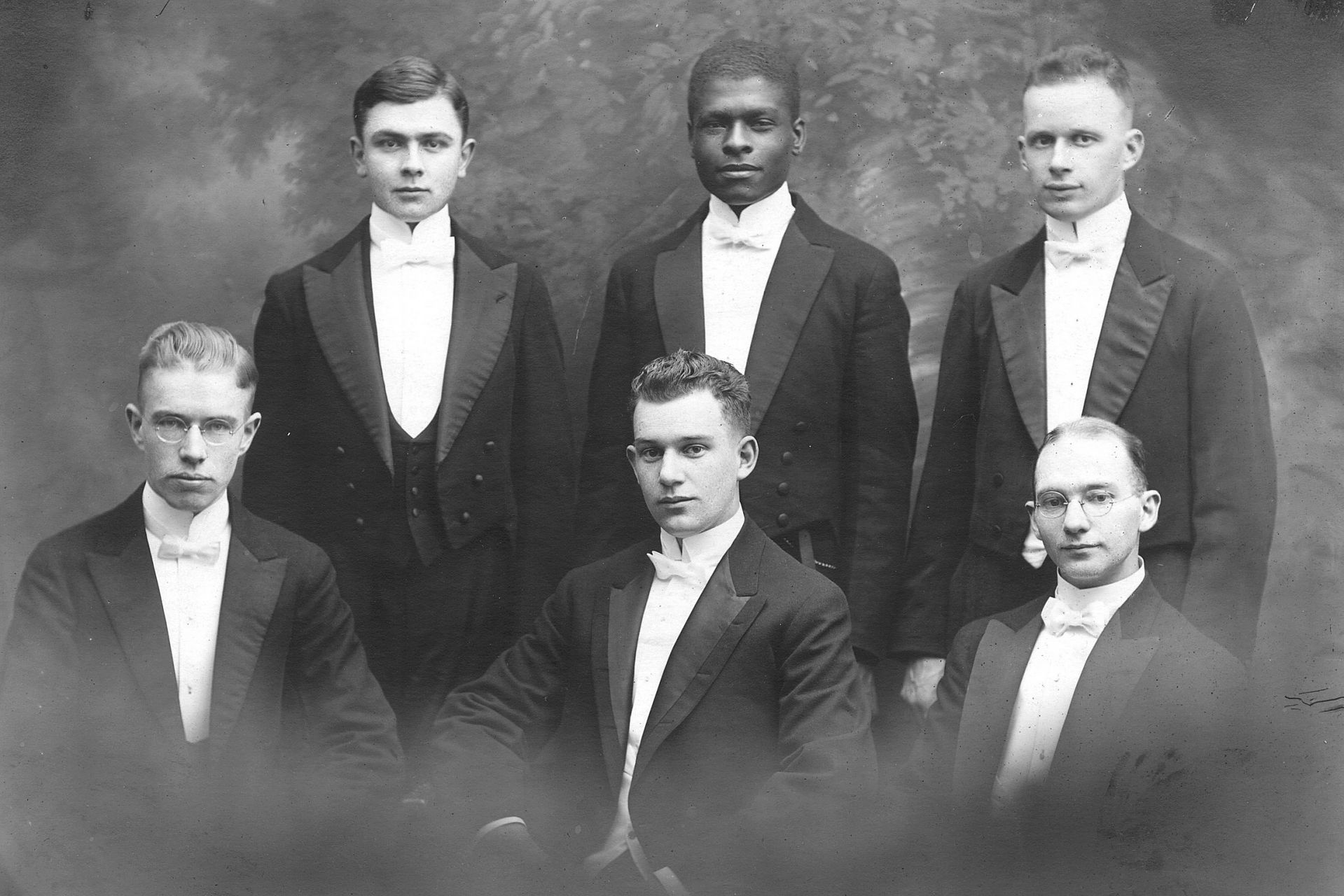

Just a few days before, The Bates Student, in a story filling nearly the entire front page, called out his winning performance in Bates’ triangular debates vs. Clark and Tufts, in which one Bates team debated Clark in Lewiston, and another, Mays’ team, headed to Medford to face Tufts.

By April 1919, Mays was a confident junior, well on his way toward accomplishing what he set out to do by attending an integrated Northern college: to prove “that superiority or inferiority in academic achievement had nothing to do with color of skin” and to “dismiss from my mind for all time the myth of the inherent inferiority of all Negroes and the inherent superiority of all whites — articles of faith to so many in my previous environment.”

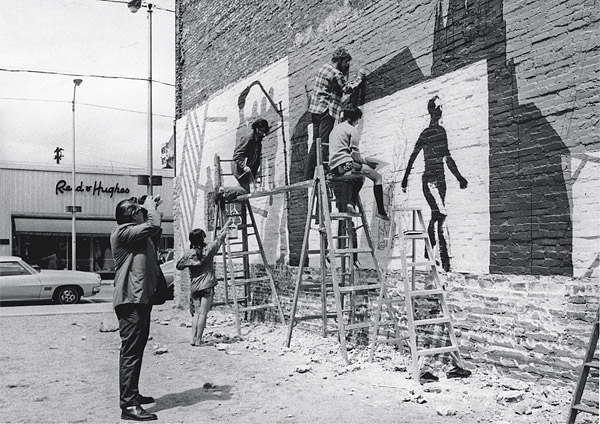

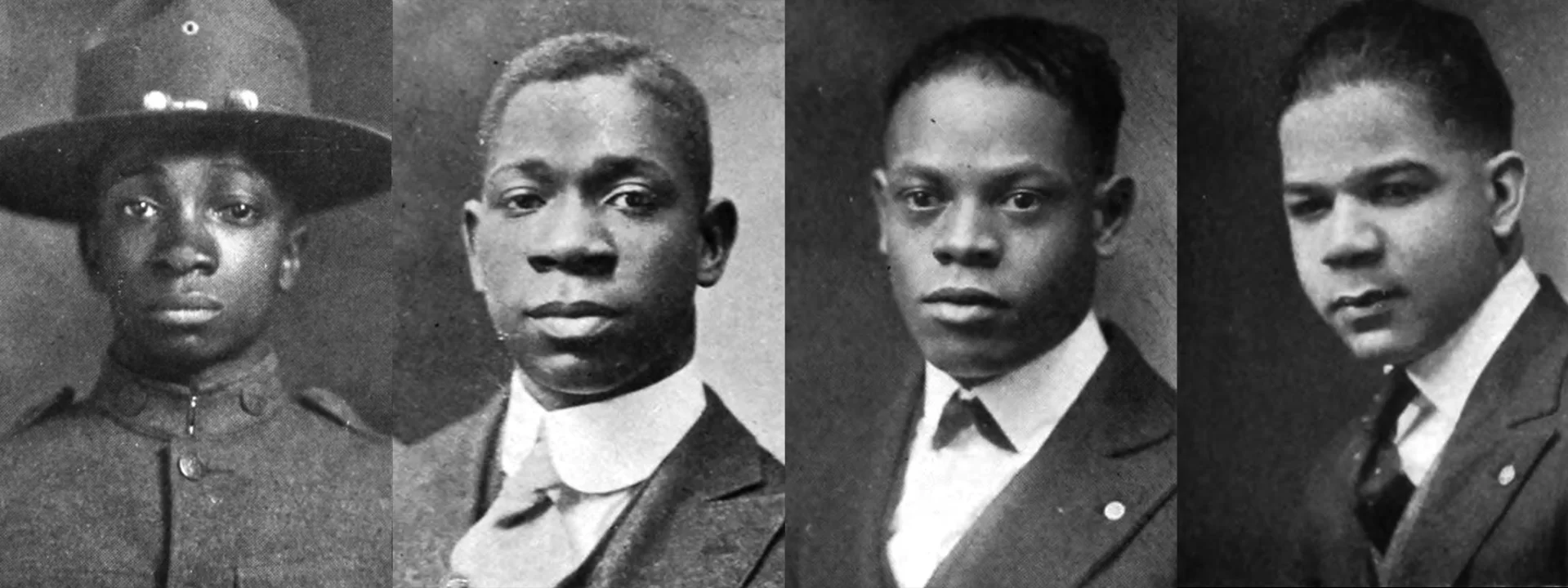

We know that Mays — who would become one of the leading civil rights leaders of the 20th century — went to see The Birth of a Nation in Lewiston from two sources: his autobiography, Born to Rebel, and an undated TV interview, likely filmed in the early 1980s, when Mays was in his 80s. In the autobiography, he describes seeing the film “with other Negro students at Bates.” While he doesn’t specify, his companions might well have been Birtill Barrow, a senior from Barbados; his brother, Ellis Barrow, a classmate of Mays’; and two sophomores from Washington, D.C., Roscoe McKinney and Lewis Moore.

And this wasn’t your typical modern theater with 100 or so seats. This was the grand, opulent, and bygone Empire Theatre on Main Street, about a 20 minute walk from campus and, in 1919, in its infancy as a motion picture theater. The Empire had nearly 600 seats on the ground floor, another 360-plus in the balcony. There were also eight box seats — akin to today’s luxury boxes at sports stadiums — with 44 seats. And an upper balcony, known as the “family circle,” offered another 500 seats.

(Side note: Theater owners named the upper balcony “the family circle” to push back against a perception that these cheap seats drew a rough crowd. “Sociologists railed against the cinema in the early 20th century,” Nero explains. “They saw it as a place of license, where social deviance — for-profit liaisons — could happen because it was dark.” It wasn’t limited just to movies either; as early as the 1860s, Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., had named its upper balcony the “family circle” to address that stigma.)

The film screened at the Empire over three days in 1919, April 28–30, with matinee and evening shows each day. Admission ranged from 25 to 50 cents, depending on the seat. A big ad in the Lewiston Evening Journal proclaimed, “Still The Greatest Film Ever.” Depending whether or not the film drew a full house, upwards of 5,000 local citizens could have seen the film. The population of Lewiston and Auburn was just under 49,000 at the time.

Seated in the Empire Theatre, Mays and his Bates friends would have had good reason to grow uneasy as Flora scrambles to the top of the mountain to escape Gus. Finally, she is trapped on the precipice with no place to go. Gus draws near. And rather than be touched by a Black man, she jumps to her death. (Nero notes that 1992’s version of Last of the Mohicans has a nearly identical scene: Alice jumping to her death rather than being with Magua.)

In one of the key scenes from The Birth of a Nation, Gus, played by a white actor in blackface, begins his pursuit of Flora, from her home into the woods and to the top of a hill.

And that’s when all hell breaks loose, as May recalled in the TV interview. Though he mis-remembers the scene as Flora drowning, his recollection of what he felt is vivid:

“The reaction [the scene] had for these Maine boys [in the theater] was so violent…when the white woman ran into the water and drowned, instead of having a black man touch her.” In Born to Rebel, he also described how the scene “evoked violent words and threats from the audience.” After the movie ended, “we ran to the campus. We didn’t know if we would be mobbed or not. We didn’t know if they were chasing us or not. That was the first real experience of how powerful Birth of a Nation was.”

Nero can picture young Mays and his friends in a state of terror. “It had to be frightening to suddenly recognize, to look around and realize that you are one of a handful of Black people in the cinema. Are people yelling, ‘Oh my God!’? Are people yelling about the N word? He doesn’t reveal that except to say that violence was instigated. And the violence was so intense that he and the other Black students that he was with felt it necessary to run back to school.”

Benjamin Mays describes seeing The Birth of a Nation while at Bates in April 1919:

Nero suggests that we ask ourselves who was in the audience with Mays and his friends that night. Throughout the late 1800s, hundreds of thousands of French Canadians had emigrated to various New England states, many settling in Lewiston. Between 1910 and 1920, Lewison’s population had grown by 20 percent.

“These people would not have had any direct experience with blackness,” says Nero. But then along comes The Birth of a Nation, which, during its three-day run in April 1919, would serve to “socialize the understanding of anti-Blackness.”

And by 1920, newer citizens of Maine would see other examples of Blacks being erased from the cultural landscape. There were various Civil War monuments in the state featuring Union soldiers and honoring their sacrifice, such as these words on Lewiston’s monument “Justice demanded the sacrifice. We willingly offered it.”

But just as in the South, the Union monuments don’t reflect or represent Black America. “They represent the white Union soldier and the Union cause. That’s one issue.

In Lewiston, with its large immigrant population, there might have only been a “dim memory of the Civil War,” Nero says. With The Birth of a Nation, “they’re being told that we have this internal enemy in our presence, and it’s the Black. If you are a new American or a new arrival, and you see this film, you immediately learn: the enemy is inside of the nation, inside the borders of the country. It’s the Black: and that might be useful if you are an immigrant. It’s not us. It’s them.”

The Birth of a Nation begins with the Civil War tearing apart America and infamously ends with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the idea that the KKK saved America.

“What a film like The Birth of a Nation does is suggest that in order for reconciliation between North and South to happen, Blacks have to be punished — anti-blackness is central to this reconciliation. Blacks have to be subordinated, pushed into place. Blacks have to be shown as profoundly” — and here Nero pauses as he chooses the word — “horrible.”