“Okay. I am going to just say it: I’d like to see a woman ask a question,” economist Cecilia Rouse said to her Bates audience.

“A student,” she clarified, and a laugh rippled among the students, faculty, and staff who were asking some Q’s during a lively Q&A session after Rouse’s talk in a Pettengill Hall classroom back in April.

Rouse is no stranger to commanding a room: She chairs the White House Council of Economic Advisors. And as a professor of economics at Princeton, she’s certainly no stranger to speaking with students.

(Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

She’s also a woman, and thus no stranger to the fact that economics is infamously dominated by men, a fact that “is not a trend, but always the case in economics — everywhere,” says Lynne Lewis, Elmer W. Campbell Professor of Economics at Bates. With colleague Nivedhitha Subramanian, an assistant professor of economics, Lewis welcomed Rouse to Bates on behalf of the student club Women in Economics, the Department of Economics, and the President’s Office.

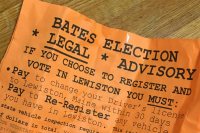

Nicknamed WE@Bates, the economics club was founded by Lewis and a colleague in 2018 following high-profile national media accounts of discrimination against women in economics.

The discrimination was “nothing new,” as Lewis said in 2018 but “at the same time it was great to see the topic getting attention.” The New York Times noted just last year how “gender and racial gaps in economics are wider, and have narrowed less over time, than in many other fields.”

Among economics majors at U.S. colleges, it’s understood that about 70 percent are men and 30 percent women. At Bates, 74 percent of the economics majors this year were male. That’s within a senior class that is fairly gender balanced at approximately 46 percent male, 52 percent female, and 2 percent transgender and/or gender non-conforming.

Open to all students, Women in Economics focuses on supporting female-identifying students who wish to study and explore economics, finance, consulting, and related fields through various efforts, including invited guest speakers like Rouse, who can expand the notion of who can both major and thrive in economics.

Jane Dodge ’24 of Winchester, Mass., is the community liaison for WE@Bates. She’s not an economics major — English is her choice — but knows that economics at the college level has the reputation of creating “finance bros,” a culture that make it hard for female students to see themselves thrive in the field of study.

Students often have a preconceived notion that studying economics is “all about [going into] finance and making money,” says Dodge. But it can be other things. “It’s about looking at how people make choices and ways wealth can be distributed” — which has value that spans most academic majors, she says.

As part of her visit, Rouse spent informal time talking with students, including a gathering in the Fireplace Lounge in Commons, where she offered direct encouragement and advice. At her evening talk, she was introduced by President Clayton Spencer and interviewed by Lewis and Subramanian.

An example of economics’ multidisciplinary reach came during Rouse’s talk when she addressed economics and energy in the context of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Even though the U.S. is “largely energy independent” the invasion has “raised the issue” — mostly due to soaring gas prices — so that “as we make this transition to clean energy, we need to be independent there too, because we don’t want to find ourselves at the mercy of another country,” says Rouse. “We need some energy independence.”

Rouse suggested looking at politics as a component of economics, rather than an opponent.

For Caitie McGlashan ’22 of Hopkinton, N.H., Rouse’s insights into how politics, policy, and economics can inform and benefit each other were eye-opening.

It’s tempting to think of politics as “this nuisance that prevents beneficial economic policy from getting through,” says McGlashan, vice president of WE@Bates. But Rouse suggested looking at politics as a component of economics, rather than an opponent.

“When we have some sort of constraint in economics, we incorporate it into our modeling and use it to make the model more realistic. We don’t just ignore it,” McGlashan explains. “So Rouse framed politics as a constraint that can be modeled into the likelihood of a particular piece of economic legislation being effective.”

The trifecta of politics, public policy, and economics are also all components of a slightly older — but ongoing — issue a little closer to home: COVID. Lockdowns at the beginning of the pandemic have had lasting effects on the economy, and it’s only made it more clear that a single decision can have widespread consequences.

COVID variants keep appearing, but no nationwide lockdown has been announced since the first one in March of 2020. Cases are still high, even with vaccination rates, so why hasn’t the economy been hit as hard as that first time?

“Two years ago we knew nothing about this virus,” says Rouse. Information battled with disinformation. “Remember, people were wiping down their groceries — and being told they didn’t have to wear masks, [that COVID] was overblown. Shutting down the economy was what we just needed to do. It was a very extreme policy simply because we didn’t have the tools.”

But now we have those tools, says Rouse. We know what upticks in cases look like, we know ways to react and mitigate exposure, and more importantly, we have vaccines; all tools that affect the way an economist calculates what actions to take.

And for economics students and those considering studying economics, the job market for economists is “red-hot” right now, says Rouse.

Economics doesn’t afford a single path or a single tool for its majors. “It’s a fantastic toolkit to help understand so much of the world around us,” says Subramanian.

“You’re able to ask important questions and use data to answer them,” says Lewis. True, it can be a means to a specific career goal, as are many academic majors, but it’s also about “finding ways to make people better off, and crafting policies that address poverty, discrimination, environmental pollution, and inequality.”