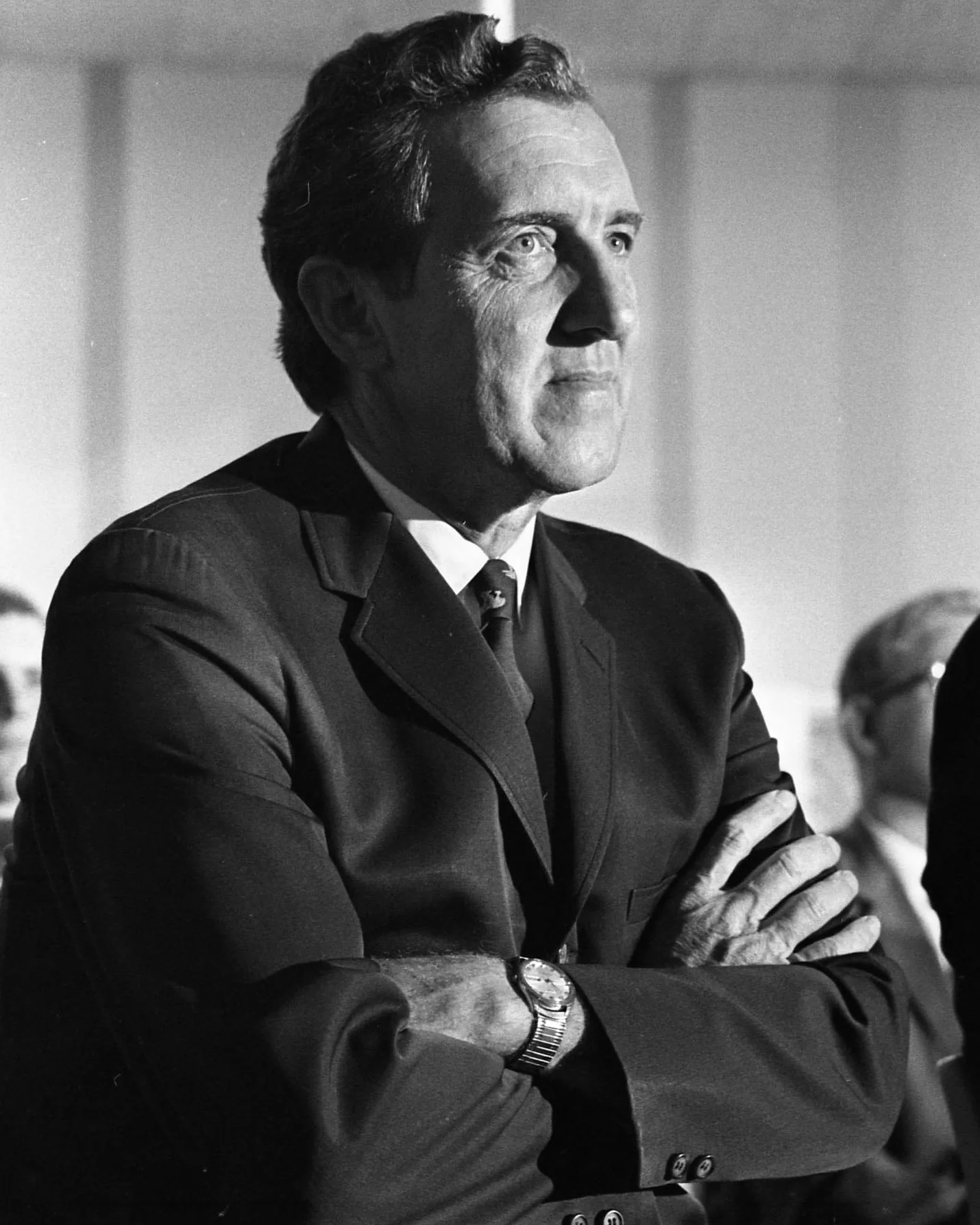

Edmund Muskie ’36 is considered a prime mover and leading voice of modern American environmentalism. In many ways, he quite literally was the voice.

Fifty years ago, as a U.S. senator from Maine, Muskie’s Bates-trained voice sounded across the country. From Sacramento to Millinocket to Pensacola, he explained in lucid and compelling and logical terms why a new law to protect water from pollutants was not just good for Americans and America, but absolutely necessary for our survival.

On Oct. 18, 1972, the Clean Water Act became law, all because of Muskie, who understood to his Maine-born core that protecting the natural environment was inseparable from protecting what he called “our total human environment,” incorporating economic and other realms.

In speaking to audiences around the country — audio clips are below, from the Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library — Muskie followed an important principle of argumentation and debate learned at Bates: Understand, respect, and speak to your audience.

“The technical term is argumentum ad populum,” says Jan Hovden, lecturer in rhetoric, film, and screen studies and director of debate at Bates. “Muskie is appealing to the values of the common people and making sure that they are at the forefront of the arguments that he’s making.”

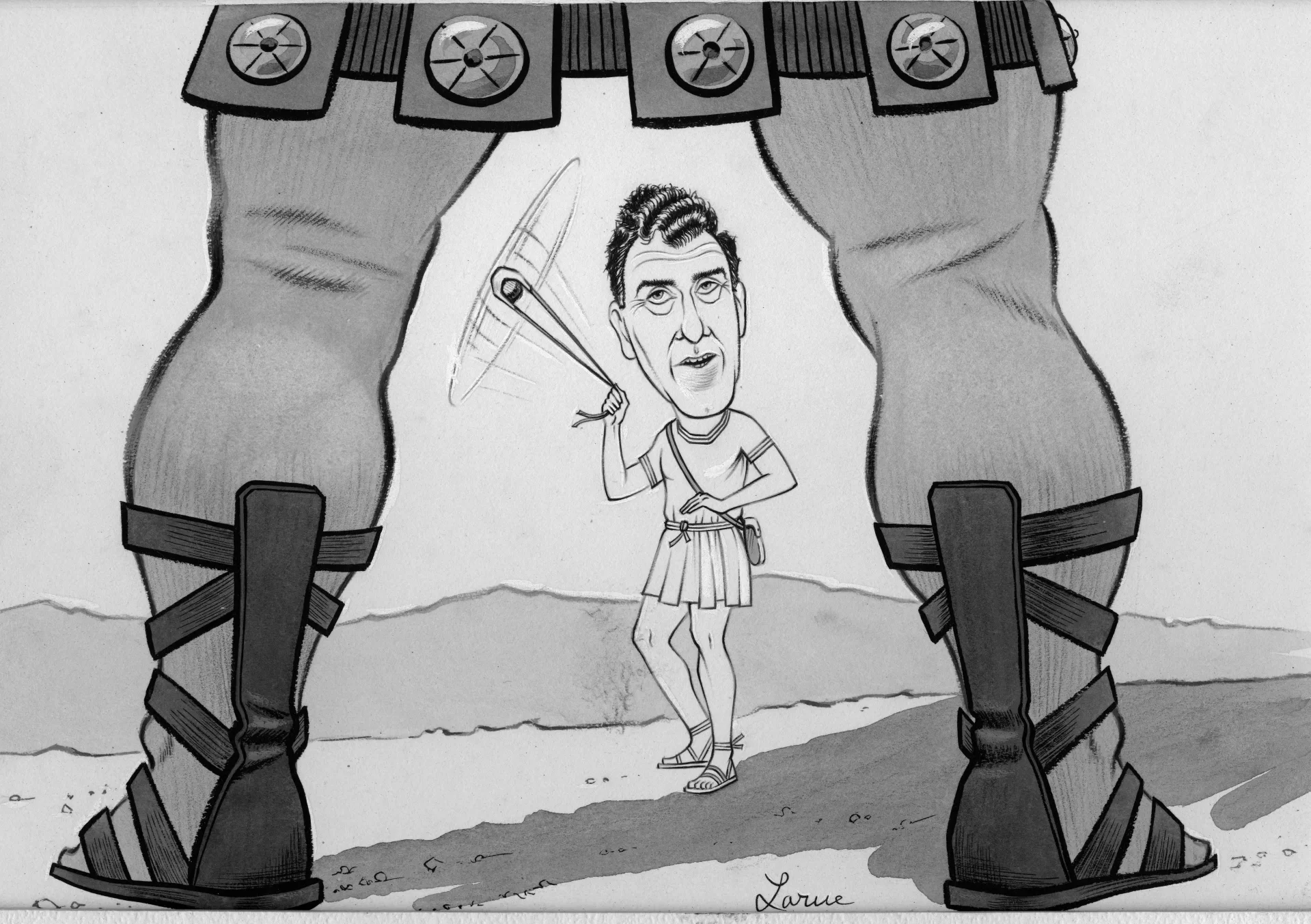

Muskie was a shy kid who came to Bates from Rumford, Maine. He blossomed through public speaking and debate, taking four semesters of public speaking, all taught by Brooks Quimby, Class of 1918, a professor of argumentation and speech from 1927 to 1967, and namesake of the Quimby Debate Council at Bates, which Hovden coaches.

So Muskie probably heard Quimby say to him and his classmates, as the professor wrote in his book, So You Want to Debate, “Don’t mumble, be careful to pronounce every syllable.” He probably heard Quimby’s advice to “listen to Lowell Thomas on the radio” and to “watch for poor diction, ‘git’ for ‘get.’”

A listener will also hear many pauses in Muskie’s speeches.

“He’s using it for effect,” says Hovden. Muskie is allowing his words to sink in with his audience. “Pauses are an incredibly important part of speech-giving. Like after giving a startling fact, you just want to let that sink in. You need to pause for probably three seconds. And that’s really hard for people to do.”

Muskie’s formal speaking style is a thing of the past, suggests Hovden, “very consistent with how you would expect an educated man of his stature to speak during that time period.”

Fifty years ago, science and scientists were not disputed, and Muskie gained fame for knowing the science of pollution. “Muskie was speaking when science was prominent,” says Hovden, “when being able to establish yourself as an expert about something, or as an intellectual elite, was actually seen as good. People were looking for educated people to figure things out. Whereas today, that’s just not the case.”

Speaking to Democratic supporters in October 1970 at an Elks Lodge in Millinocket, Muskie offered a raison d’être for his work to advance environmental legislation. He had been asked his one wish for Maine. He said, “I hope we find a way to create economic opportunity for all people without destroying the beauty that is this state.”

“He’s trying to emphasize the idea that these two goals are not mutually exclusive,” Hovden said. “Any path going forward, we can’t just say one or the other. We have to do both. This is what has to happen.”

Muskie insisted that it was not only possible but imperative to think about the “total human environment” — the natural, economic, health, and social environments. “He was incredibly consistent,” says Hovden. “It’s so impressive.”

March 24, 1970: Muskie speaks to the conference of the National Association of Counties

Muskie began many talks with what today are called “dad jokes.” As Hovden explains, “Jokes can be a very effective introductory part of a speech or even used throughout the speech — with some big caveats. It can’t be something that offends your audience members. The audience has to get the joke. The focus isn’t on the joke at the expense of what it is that you’re talking about. Muskie seemed to understand that.”

In March 1970 in Washington, D.C., Muskie began with a joke as he addressed 500 officials from 50 states representing local counties that depended on federal funding for anti-pollution measures.

The joke is about “benign neglect” — a swipe at President Nixon, who was advised to adopt this laissez faire strategy on racial strife:

Transcript:

[With every new administration here in Washington] we get a whole new lexicon of phrases anyway. One of the most interesting ones, that ought not to apply certainly to this field, is the phrase “benign neglect.”

You know, I have an old friend of mine up in Maine, he’s a Republican, too, 70 years old, who’s lived all his life on a Maine farm. And I asked him if he had heard of that phrase, benign neglect, he said he had. And I asked him if he knew what it meant. He said he did. So I asked him if he wouldn’t explain. Well, he said, “If you were standing on a bridge and watching a man drown, and did nothing about it, that would be neglect. But if at the same time you smiled, that would be benign neglect.”

Muskie sometimes uses the phrases “whole society” or “total human environment” in his call for a “total strategy to protect the total environment.”

Transcript:

And we should all understand that we are all in the same boat. That what happens to our environment must make a difference to all of us, whoever we are. And that what happens to each of us, must make a difference to the rest of us. So we must reclaim the total human environment.

Oct. 10, 1970: Muskie speaks to citizens at an Elks Lodge in Millinocket, Maine

Asked on a local radio show what his one wish for Maine was, Muskie replied: “To create economic opportunity for all people without destroying the beauty that is this state.” The “Ken” and “Bill” in the clip are probably fellow Democrats, then-Gov. Kenneth Curtis and then-Rep. Bill Hathaway.

Later, at the Elks Lodge, he says that after reflection, that first answer was the best one. “He’s using repetition for effect,” says Hovden. “He’s really just saying, ‘This is what has to happen, and, you know, after I’ve thought about it, yeah, that’s still what has to happen.’”

Transcript:

I was asked on your radio this afternoon, it was rather a surprise question that I understand Bill was asked and Ken was asked, if I had but one wish that I could make for Maine, what would that wish be? My answer was that I hope we find a way to create economic opportunity for all people without destroying the beauty that is this state. So I say that was my very quick reaction [applause], but now that I’ve had a few hours to think about it, I can’t think of another wish that I would make. [more applause]

In this clip, Muskie asks his audience to imagine protecting the environment “through different eyes.”

Transcript:

But the challenge that is in it for us, is that we begin to look at this precious resource through different eyes; that we begin to be more selective about the uses to which we’re willing to put it; that we begin to think more in terms of public ownership of these shorelands, both lake and ocean, to ensure that the public as a whole has reasonable access to it; that we adopt the kind of public policy that ensures that a reasonable proportion of these wildlands be retained in that state so that our children, as well as we, can remember what it’s like to camp out where you can hear a loon, to walk through miles of wilderness where you have the impression no one else has ever been.

In this clip, “Muskie appeals to Mainers’ strong feelings about their land,” says Hovden. “How Mainers love their shores, their forests, their mountains.”

He’s also talking about protecting Maine from outside interests. “I grew up in North Dakota, and it’s totally the same way,” said Hovden. “We don’t want outsiders because they won’t value natural resources the same way that we do. It’s subtle, but if you’re a Mainer you recognize it.”

Transcript:

The population pressures are suddenly going to pour people across the borders of our state, not only for recreation or summer vacations, but as a place to live. Already you’ve been reading in the Portland Sunday paper about the speculation that’s going on in Maine shorelands. And it is.

We don’t know who the speculators are, we don’t know how much land they bought up. We don’t know what purposes they’ll put them to, but we know the prices are climbing. There’s 2,500 miles of this kind of shore. We don’t know how much of it has already been the subject of speculation. Now, when the speculators finally decide that there’s a market for some kind of commercial activity as yet undefined, to what uses are they going to put that shoreland? We don’t know. And the speculation is going to creep inward to the lake shores all over the state.

Jan. 26, 1972: Muskie speaks to voters in Pensacola, Fla., about President Nixon’s hostility to the Clean Water Act

Muskie was on the campaign trail in Florida, visiting a notorious pollution site in the early 1970s — Escambia Bay, which was declared “dead” by the local fishing association in 1971.

The joke about Nixon’s revolutions “not lasting very long” is a reference to Nixon calling for a “New American Revolution” in the form of unrestricted funding to states during his State of the Union address.

Transcript:

Two months ago, the Senate by a vote of 86 to nothing approved the Water Quality Act of 1971. It is a tough and far-reaching piece of legislation, the product of my subcommittee’s work. It was unanimously supported by the subcommittee, by the full committee, and by the Senate. It would do what needs to be done to clean up bodies of water like the Escambia Bay. [The legislation] was written to help you.

But President Nixon, who a couple of years ago devoted a major part of his State of the Union message to the fight against pollution, who this year devoted, I think, one sentence to the same cause — his revolutions don’t last very long [laughter and applause] — is now making every effort and enlisting all the support he can to water down that bill on the House side of the Congress.

Oct. 28, 1973: Muskie speaks to a nonprofit citizen’s environmental group, the Housatonic Valley Association in Newtown, Conn.

Though we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of the Clean Water Act now, Muskie himself considered 1970’s Clean Air Act his greatest achievement. Both required assiduous defending — for example, $18 billion had been allocated by the federal government to construct municipal water treatment plants but that level of support had been undercut by the Nixon administration.

This clip is a favorite of Hovden’s for how Muskie sets himself off from the economic elites, personified by The Wall Street Journal; shows his scientific understanding of pollution issues; and makes a connection to the audience, telling them that they don’t have to understand the science to know what pollution is.

“He’s setting up the dichotomy between the economic elite and the scientists,” says Hovden. “And he’s saying, ‘Even if you all don’t believe the science or don’t understand the science, this is how you personally know. And you all know.’”

Transcript:

The Wall Street Journal accused me of doing my scientific research by looking out the window of an airplane. And they quoted one of my recent speeches in which I had said that as I returned from Maine to the Senate following the August recess, I saw one unbroken dirty air mass covering the land, urban and rural areas alike, and darkening the sun.

Well, I was a little upset about the editorial because The Wall Street Journal was obviously trying to impugn the standards we set in the Clean Air Act and blatantly ignored the well-documented fact that those standards were based on health data produced by the Public Health Service.

But on second thought, I was even more upset that the Journal considered it irrelevant to public policy that dirty air is a visibly offensive intrusion upon the daily lives of millions of helpless citizens who have no choice but to breathe it. This isn’t to say that we shouldn’t get the best scientific evidence we can of the impact of pollution. We must vastly expand our knowledge. We must identify the biological limits of our environment and we must identify the margins of safety which are necessary to protect us in areas of uncertain knowledge.

But pollution is more than parts per million or gallons per hour or BOD [biological oxygen demand] or other scientific measurements. As citizens, you know what dirty water is. You know when you cannot swim in the Housatonic River, you know when those tributaries you used to fish no longer have trout. You know that’s pollution. And I’m not sure you’re interested in the exact quantity of suspended solids or the oxygen demand in the river, but [what] you are interested in is getting an unhealthy environment healthy, getting a dirty river clean. And we share that goal. And the 1972 Clean Water Act is intended to achieve that goal.

It’s fun to hear Muskie use his physical presence, as in this clip, where you can hear him banging the lectern as he cites three finite resources.

Transcript:

What we are talking about are three finite resources: air, water, and fossil fuels.

Ultra-consistent in messaging, Muskie here talks about how the pressing energy crisis is not a reason to pivot from solving environmental issues. It’s about the total human environment.

Transcript:

We’re going to have to find renewable sources of energy at some point to deal with the energy requirements of this planet. But there is that possibility with respect to air and water. They will serve our needs only to the extent that we clean them up for reuse. Not talking about aesthetics now.

I’m not talking about what’s pretty to look at. I’m talking about two resources that are absolutely essential to human activity from simple breathing to providing the means for this industrial society to work — air and water. To the extent that you don’t clean them up for reuse, to that extent do you build up the limitations of the future.