On Oct. 14, 1899, the first touchdown was scored on Garcelon Field — without fanfare or recognition.

The diminutive Bates athlete who plunged one yard for the historic score never scored another, yet propelled himself onward to Harvard Law School, the presidency of the 30,000-member American Bar Association, and from there to help defeat President Franklin Roosevelt’s controversial “court packing” scheme.

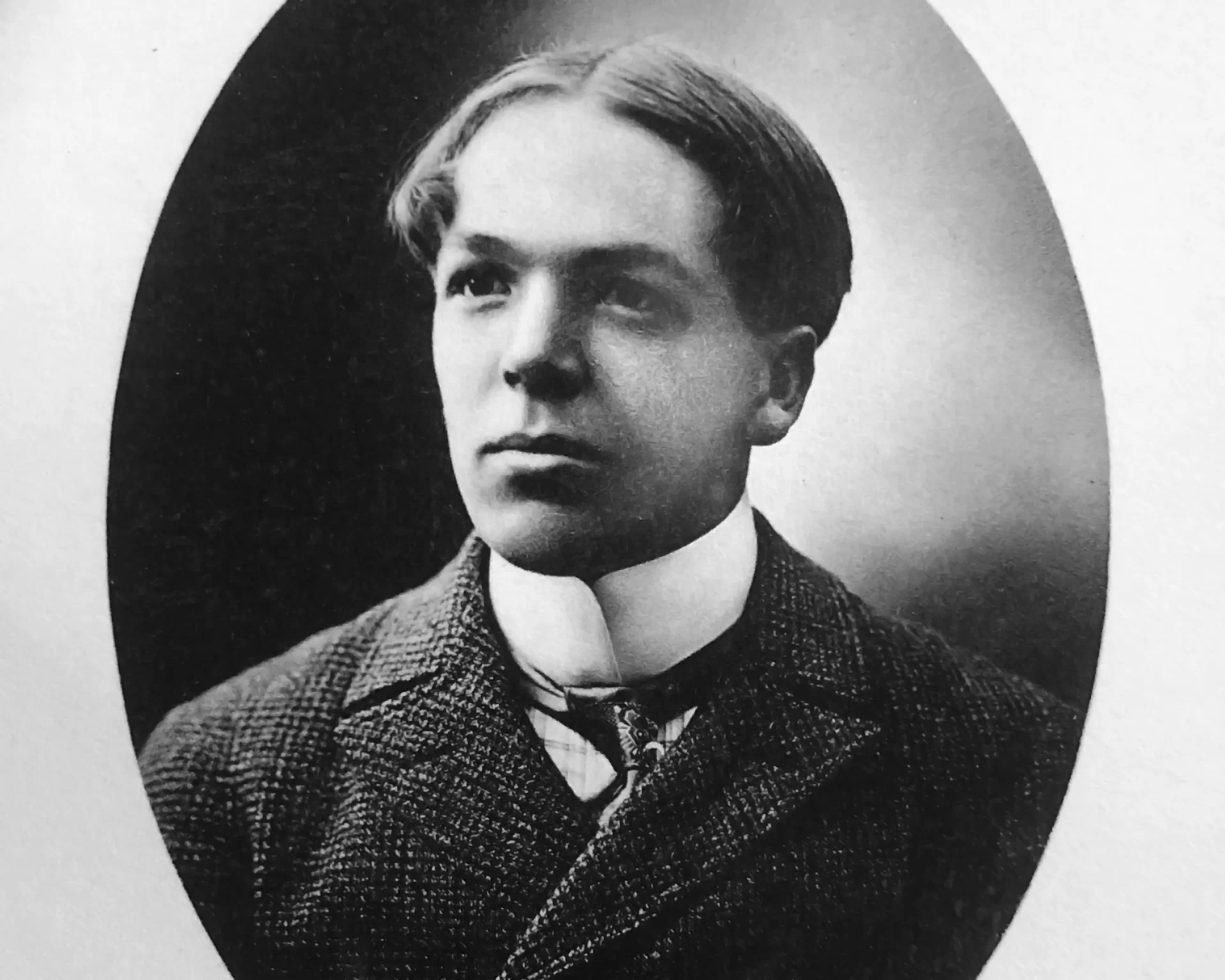

The eldest of Amaziah and Rosella’s three children, Frederick Harold Stinchfield was born on May 8, 1881, in the Washington County town of Danforth in far eastern Maine. The Stinchfield family was prominent in the town; his father ran a country store and the local post office and served in the Maine Legislature.

Washington County town of Danforth, in far eastern Maine, and made history as the first Bates football player to score a touchdown on then-new Garcelon Field. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

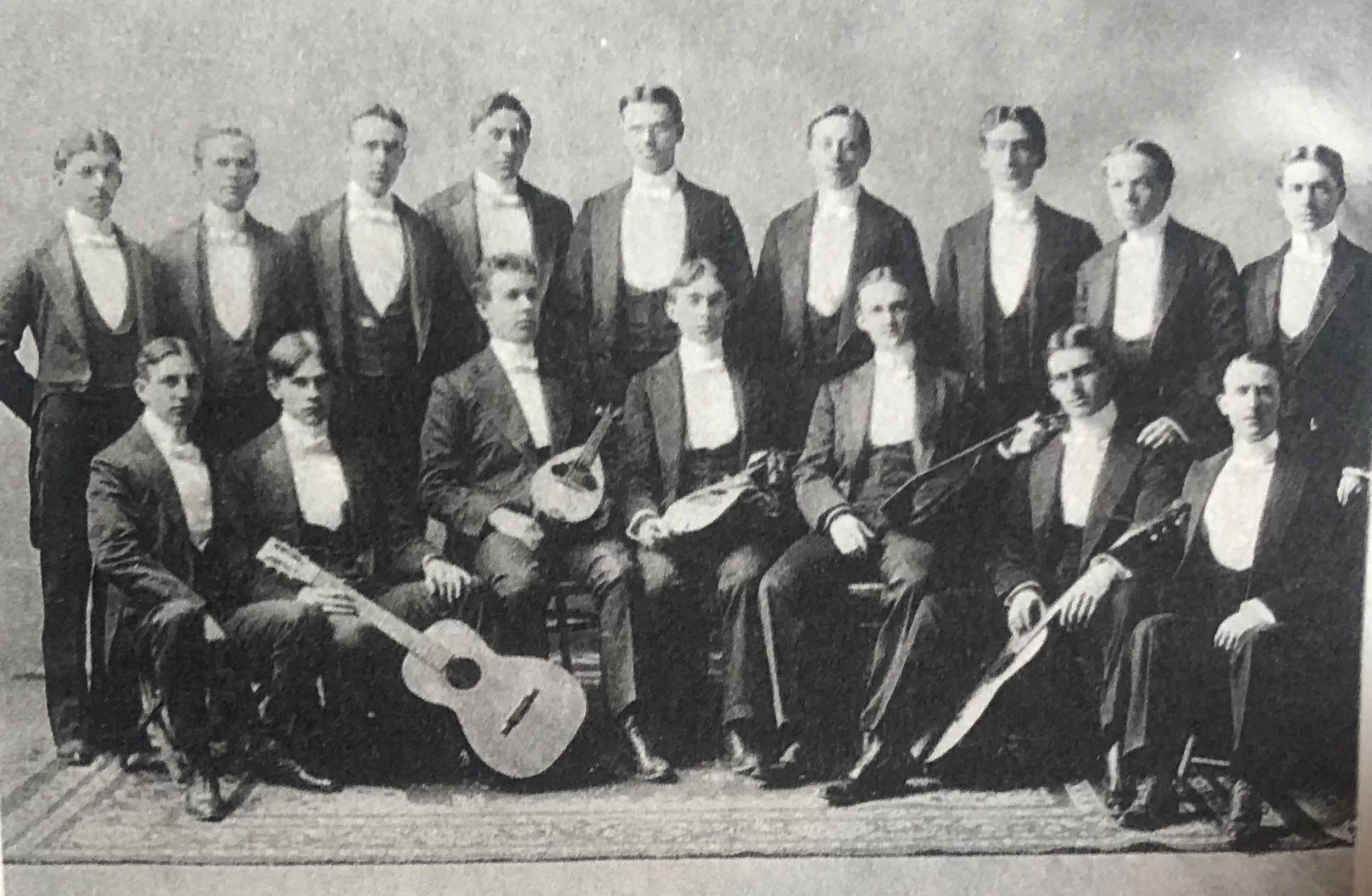

“Fitted” at Lewiston High School, Stinchfield and his classmates entered Bates in fall 1896. The class had 75 members, “two-thirds…young men — certainly all will agree, a right proportion,” declared The Bates Student. “Already they have given evidence of physical prowess, and we believe many of them will shine on the athletic field.”

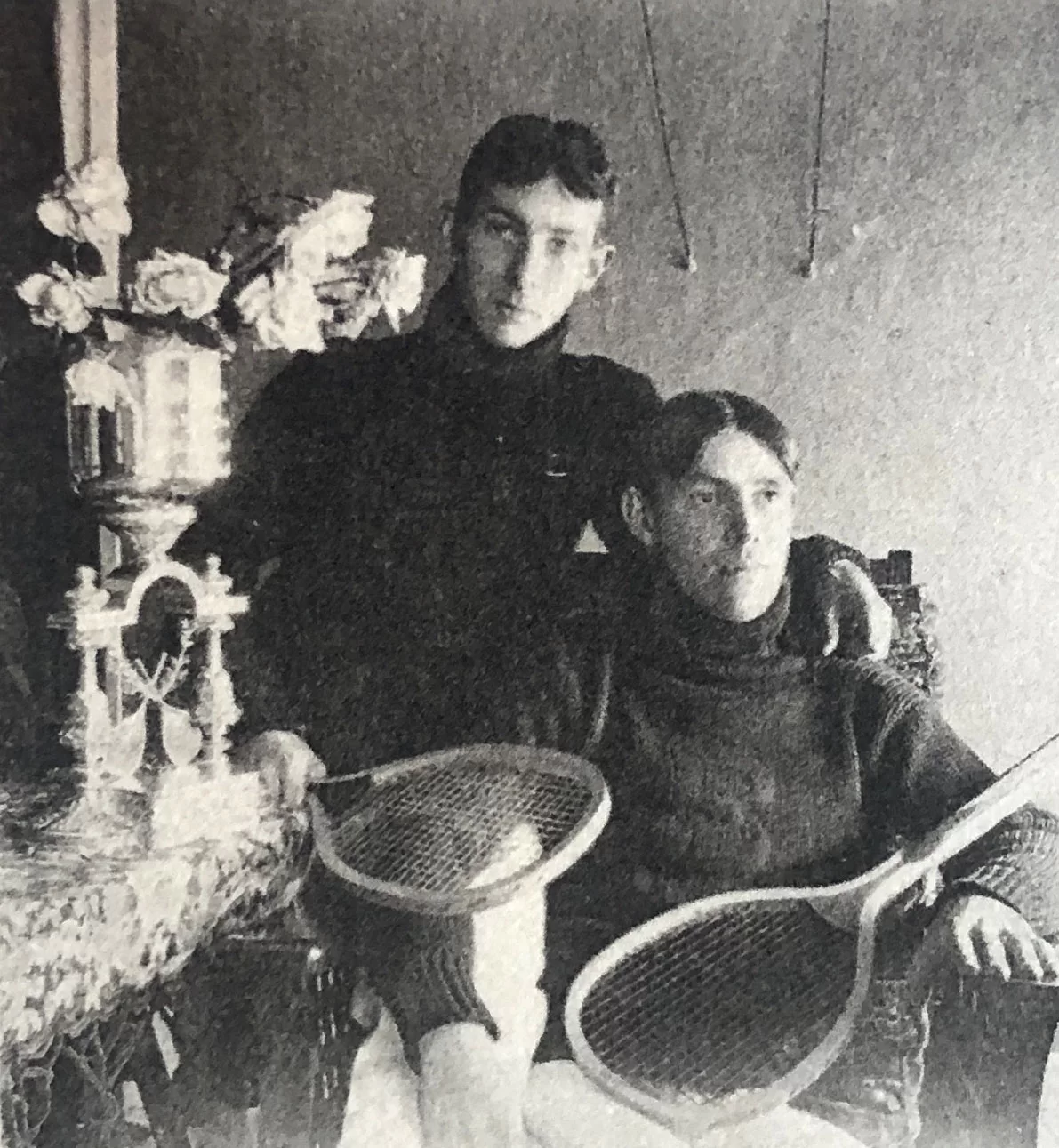

Plunging into campus life, Stinchfield teamed with classmate Ferris Summerbell to win the doubles championship in the College Tennis Tournament in October; Stinchfield fell to his more-skilled partner in the singles finals “in a hotly contested deuce match.”

In fine Bates form, he soon entered debate. In the year ahead, Stinchfield would argue the negative to the question “Is the English government superior in form and operation to the government of the U.S.?”

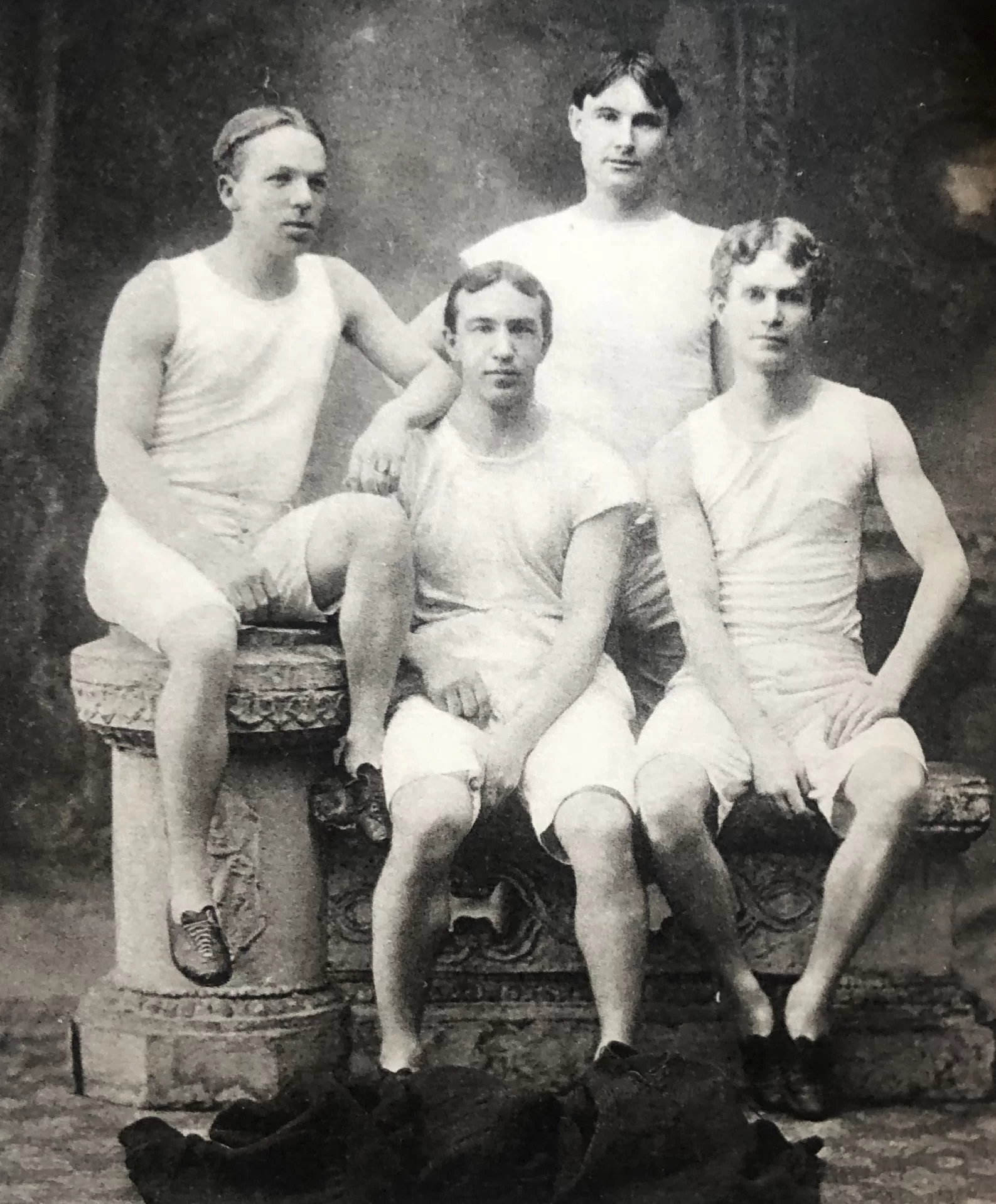

In June, he competed in the third Annual Maine Interscholastic Athletic Association track meet at Bowdoin’s new field. The 15-man Bates squad included football stars Thomas Seth Bruce, Class of 1898, of Virginia, and William Allen Saunders, Class of 1899, of West Virginia.

Sophomore year, Stinchfield and Summerbell defended their college doubles championship. But the big story on campus was football.

The 1897 team went undefeated (4-0-1) and won the Maine State Championship under captain Nathan Pulsifer at halfback, versatile linemen Bruce (six-foot-one, 178 pounds) and Saunders (five-foot-10, 173 pounds), and quarterback Royce Davis Purinton. There was apparently no room on the team for Stinchfield — who seems to be on the short side in all photos — but at the Class Field Day in May, Stinchfield displayed his speed, placing second in the 220-yard hurdles.

1898 was Bates’ greatest football season ever. The team went 6-0, won the Maine Championship, shut out Bowdoin, and didn’t allow a score in college play. Stinchfield, now a junior, played on the second team, seeing the field only once, in a 35–0 route of New Hampshire. Leading 30–0 at the half, “Bates put in seven of her second team” including right halfback Stinchfield.

Home games back then were played at Lee Park, a city commons at the intersection of Sabbatus Street and East Avenue, known for hosting traveling circuses. But Garcelon Field was already in the works. Bates had solicited contractor bids in July 1898, and work continued through the summer and fall, and by spring 1899, was baseball-ready, sort of.

The Bates President Report of 1899 lauded the new field’s pleasing aesthetics and frugal economics: “One of the most satisfactory changes has been the grading of the former ugly pasture field east of Roger Williams Hall and its conversion into Garcelon Field with its ample grounds and tasteful grandstand.” The cost was $8,000 but “would have required nearer $10,000 but for the enthusiastic help of students in removing stumps and in grading.”

The Bates Student, in contrast, emphasized the pains of the student labor in its account in June 1899. “We all had a hand in transforming the rough uncouth pasture into this fine level park. Even the cedar posts surrounding it stand as monuments to the blistered hands, aching limbs, and weary bodies, which we carried home after the day’s work.”

On May 30, 1899, Nathan Pulsifer, captain of football and baseball, added his name to Garcelon folklore by smashing the first home run, against Bowdoin.

It was a “drive to centre field, which proved to be a home run, because of the fielder’s inability to field the ball, which had gone into a ditch in the rear of the yet-unfinished field,” reported the Lewiston Sun, adding that “Pulsifer’s home run isn’t done every day — neither is there so convenient a place to lose the ball.”

Late innings of the game saw “choking, blinding, suffocating clouds of dust (that) rolled up from the new clay field.” But the new field was overall impressive: “When the dust lay quiet, the scene was one to inspire both artist and poet.”

In March, Bates held its eighth Annual Athletic Exhibition at City Hall. Stinchfield again flashed his speed, winning the low and high hurdles. He also played guard in a 27–25 basketball win over the Portland YMCA. At the Class Field Day in May, he won the college 100-yard dash (10.4 seconds) and 220-yard dash (25.4 seconds). Capping off an energetic third year, he claimed the Junior Essay Prize.

By fall, it was time to see who might score the first touchdown on the new Garcelon Field.

The 1899 schedule was unprecedented in difficulty, featuring games against Boston College at home, and Yale and Harvard on the road. Coming off two undefeated Maine Championship seasons, Bates had scheduled boldly — but, alas, the team had graduated its two-year captain, Pulsifer, and the battering ram Saunders. Trusty kicker Frank Halliday transferred to Dartmouth.

Still there were hopeful glimmers. “Of the new men, Stinchfield ’00, while very light, is, with the possible exception of Garlough, the fastest man on the team,” the Student reported.

A senior, Garlough had transferred to Bates from another Freewill Baptist school, Hillsdale College, which had won the State of Michigan title in 1898. In three years at Hillsdale, he had played football and won the Simpson Medal for “All-Around Athlete.”

The first game at Garcelon was Sept. 30, 1899, at 3 p.m. against Boston College. “This afternoon the champions of Maine carry the pigskin onto the new gridiron in Garcelon Field,” the Lewiston Evening Journal wrote. “There was an unusually good crowd for an opening game and in the grandstand, the fair co-eds sat in solid garnet phalanges, waiving streamers, singing, cheering, shouting as only the college girl knows how to do.”

But the entire first-year class almost missed it. On a class outing — likely the famed “Stanton Ride” enjoyed by each entering class for decades — they had taken a trolley to Lake Auburn with Professor “Uncle Johnny” Stanton where, report says, “they spent a very pleasant afternoon…The class returned in time for the football game.”

Newspaper reports noted that “Boston College is said to have a heavy team with fast backs.” Notwithstanding, Bates held BC to a scoreless tie, with Purinton at quarterback and Garlough at right halfback. The untested Stinchfield did not play.

Next week, Bates lost 28–0 to Yale in New Haven. Stinchfield, however, started the game at right half. That same month, he and Summerbell again won the College Doubles Championship, the third time in four years.

On Oct. 14, Bates hosted Colby in the opener of the Maine Championship Series. The Garcelon turf was still unscored upon. The backfield was the same: Purinton at quarterback, and newcomers Garlough and Stinchfield at halfbacks The forward pass was not yet legal. A touchdown counted for five points; the extra kick one.

In the first half, Bates received a punt on the 40 and rushed steadily to the Colby 10-yard line. Two plays later, “the pigskin is but a yard from the line.” Then history was made as Stinchfield plowed in for the score, reported with spare prose: “Stinchfield made the TD.” But the extra point kick was gushed over in suspenseful terms: “Baldwin tried the kick for goal. The wind was against him. But he did the trick prettily.” Bates led 6–0 at the half.

Bates scored again, this time by Garlough, to make the final score 12–0. Key to the win was a quick-huddle offense: “Bates had Colby on the move most of the time Saturday and at two or three times, by their quickness in line-up and action forced the Waterville men to give way repeatedly for good gains,” reported the Lewiston Evening Journal.

The Student recognized Stinchfield’s rushing efforts, noting he “played particularly well on the home team.” That was it. Nothing more. The historic first touchdown in Garcelon history was celebrated not with a bang, but with just a few syllables.

Four days later, on a Wednesday, Bates lost 29–0 to Harvard in Cambridge. In defeat, “a double pass, Stinchfield to Robinson, was used very effectively.”

Bates finished 1899 with a 3-3-1 record, defeating Maine twice but falling to rival Bowdoin. Winning three of four in the Maine Series, Bates was crowned state champion a third straight time. In those three years, Bates had lost only thrice, and only once to a Maine team. A golden era of Bates football had come to an end.

That December, 18 seniors, including Stinchfield and Garlough, accepted teaching positions over the holiday months, which was customary in those days. Stinchfield was also chosen as a substitute in the Colby debate.

In May, at the Class Field Day, Garlough took first in the 100-yard dash (10.2), dethroning Stinchfield, who ran third. Summerbell, a recent winner of the New England College Doubles Tennis Championship (but with a new partner), took second in the pole vault. At graduation in June, Stinchfield delivered the “Address to Halles and Campus.”

Ivy Day poet Blanche Burdin Sears delivered the final words to the graduates:

O’er life’s threshold to the future,

With the thought of what has been

Goes the Class of Nineteen Hundred

To the laurels she may win

And with those stirring sentiments, and the Hathorn Bell ringing, “the four years of pleasure and study were over,” the Mirror reported. “Farewells were said, old associations severed, and 1900 scattered through the world, a class no more except in love for the dear old ties and the memories of bygone days.”

Stinchfield returned to work at the country store in Danforth for his father but soon left to teach in the Philippines. That too did not satisfy: as a biographer would write, “a dislike of teaching and of a country store sent Mr. Stinchfield into law.”

The Harvard Crimson framed it this way: “In 1900, Bates College, thankful for his work on the football team, recommended him to the mercies of the world. He went instead to Harvard for a law degree.”

He graduated cum laude from Harvard Law in 1905, burnishing his athletic portfolio with a letter in basketball; he also played baseball and handball.

Reviewing a workout before the Penn game, the Crimson appraised the basketball team harshly. “Almost the entire practice was discouraging…fumbling and rough playing were also frequent.” After the inevitable 22–16 defeat, the Crimson blamed the loss on the “inability of the University players to throw easy baskets.” Stinchfield endured the outrageous slings and arrows of the Harvard press — and played two seasons.

He also played club baseball at Harvard, helping Maine to defeat the Missouri Club, 14–8, for the 1903 State Club Championship. The fault-finding Crimson noted that Maine “took advantage of a large number of errors by their opponents.”

Stinchfield was joined on the Maine Club by third-year law student Oliver Cutts, Bates Class of 1896. After football at Bates, where Cutts competed in the first intercollegiate debate tournament, he starred for the undefeated 1901 Harvard national champion football team. He was awarded All-America honors, with The New York Times later calling him “one of the greatest linemen to ever play the game.”

After graduation, Stinchfield was admitted to the New York Bar, and cut his legal teeth in the city. But, “the call to the west sounded strong,” and in 1909 he headed to Minneapolis.

His Bates teammates and classmates were also taking steps in their careers, and, by 1915, the General Catalogue reported that the 1900-era grads had become lawyers, physicians, surgeons, professors, athletics directors, major league ballplayers, principals, trustees at historical black institutes, traveling salesmen, and biologists. They had trotted the globe: Turkey, the Philippines, all across the U.S. By now, they were in their mid-30s, leaning in on careers and raising families.

Practicing at Wilson, Mercer and Swan, Stinchfield defended white collar crimes, such as grand larceny in the case of D.R. Morrow, of Sterling Securities, accused of raising $43,000 to start a “Farmer’s” Bank, then stealing it.

He argued before the Minnesota Supreme Court that an attorney convicted of espionage should not be allowed on a U.S. Senate primary ballot. He championed streamlining court proceedings by eliminating grand jury indictments except in major criminal cases.

When he made partner, the firm became Mercer, Swan and Stinchfield. In World War I, he served as counsel for the Minneapolis Draft Board and Judge Advocate in the U.S. Army.

He had a great zeal for the bar organization, receiving credit for building membership in the Minnesota State Bar Association as its president.

“Prior to his presidency of the state association, the membership of that group was small, its activities few, and its influence slight,” said the American Bar Association Journal. “This was because many members of district associations were not members of the state body. When he became president, Mr. Stinchfield succeeded in reorganizing the Bar so that all district members were given membership in the state association.”

In 1928, he married Elizabeth Shrader and had step children, John and Liz. By now, he was the senior member of Stinchfield, Mackall, Crounse, and Moore, “representing many of the outstanding interests of the Northwest.”

His civic boosterism included membership in the Minneapolis Club, the Minneapolis Athletic Club, and several hunt clubs. Along the way, he picked up golf, becoming a top amateur in the state, playing out of the toney Minikahda Club, host of the U.S. Open in 1918. He was director for the Twin City Federal Savings and Loan.

In Stinchfield’s rise to civic prominence, perhaps there are faint echoes of Sinclair Lewis’ satirical Babbit. But Stinchfield would step outside conformity in 1936, when he was named president of the 30,000 member American Bar Association. “A native of Maine, with the accent which that state endows its son still part of his speech,” noted the ABA Journal.

Stinchfield entered national affairs with a forceful voice. He declared the ABA is “the guardian of liberties and privileges under the constitution which are in danger of encroachment.”

Almost immediately, that guardianship was put to the test. The ABA organized a national response to Franklin Roosevelt’s Judicial Procedures Reform Bill, infamously known as the “court packing plan” that would give FDR the power to add Supreme Court judges to help push through his New Deal agenda.

Stinchfield said the president had “assumed and is exercising the powers of an autocrat.” In February 1937, Stinchfield galvanized opposition with an address, “Would You Destroy Our Supreme Court?” He surveyed ABA members and found that 86 percent opposed FDR’s plan.

Stinchfield, circa 1928 (Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons)

Stinchfield went head to head with FDR in the media. When the president said that the Constitution was more like a “layman’s document, not a lawyer’s contract,” Stinchfield laid into FDR, accusing him of an “apparent determination to destroy the Supreme Court.” Noting that 32 of the 55 framers were lawyers, Stinchfield said that lawyers have “made America whatever America is.” Opposed by Congress, too, FDR’s plan was eventually defeated.

When Hugo Black, an appointee to the U.S. Supreme Court in 1937, admitted to being a member of the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s, Stinchfield was there with his lawyerly observations. Noting that Black had said his own record as a U.S. senator “refutes every implication of racial or religious intolerance,” Stinchfield asked, in the press, “whether Mr. Justice Black was of the same opinion as to religious and racial freedom when he was a member of the klan as when he resigned.”

That June, Bates awarded Stinchfield an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree. In his address, he admitted that times were tough due to the Depression, but told the graduates they must “take the world as it comes to you.”

Bowdoin, too, honored Stinchfield. The citation said, in part, “like so many other native sons of this State [he] has gone to the Middle West and shown there the tenacious, bulldog characteristics so many associate with the State of Maine.”

In his visit back to Maine, perhaps he visited Garcelon Field, and remembered the long-ago touchdown, or walked onto one of the tennis courts that dotted the campus in those days.

Stinchfield died on Jan. 16, 1950, at age 68 following a heart attack in California. The Minneapolis Star said, “As civic leader, sportsman, counsel, and friend he will be sadly missed.”

Time had long forgotten that fabled touchdown of Oct. 14, 1899, the first ever on Garcelon Field, by the determined athlete, the loyal tennis partner, the undersized back in football.

After his Bates Commencement address in 1937, Stinchfield spoke to the honor seniors at the University of Minnesota that year. He challenged them to “follow the path of truth and sincerity, avoid the roads of deception and popularity, and abhor pleasant words uttered for the momentary reward of the pleased feelings of those who listen.”

The callow youth from Danforth had, in the end, stepped out from the shadow of anonymity, found his voice, and made himself known to the world.

Bob Muldoon ’81 lives in Boston. The author of the novel Brass Bonanza Plays Again, he has written a variety of historical sports features for Bates News and essays about New England life.

![Title: [Harry Lord, Chicago AL, at Hilltop Park, NY (baseball)]Creator(s): Bain News Service, publisherDate Created/Published: [1912]Medium: 1 negative : glass ; 5 x 7 in. or smaller.Reproduction Number: LC-DIG-ggbain-11489 (digital file from original negative)Rights Advisory: No known restrictions on publication. For more information, see George Grantham Bain Collection - Rights and Restrictions Information https://www.loc.gov/rr/print/res/274_bain.htmlCall Number: LC-B2- 2514-10 [P&P]Repository: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.printNotes:Original data provided by the Bain News Service on the negatives or caption cards: Lord, Chisox.Corrected title and date based on research by the Pictorial History Committee, Society for American Baseball Research, 2006.Forms part of: George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress).General information about the George Grantham Bain Collection is available at http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.pnp/pp.ggbainAdditional information about this photograph might be available through the Flickr Commons project at http://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2658871356](https://www.bates.edu/news/files/2020/10/crop-Harry_Lord_ggbain-11400-11489u-200x133.jpg)