Two years after their last post-election gathering, members of the Department of Politics at Bates reconvened to offer their expert takes on this year’s midterm election results.

Taking part and sharing insights from their specific areas of expertise were Pavel Bačovský, John Baughman, Steve Engel, Lisa Gilson, and Chris Price.

“Welcome to our biennial politics department panel,” said Baughman at the start of the webinar, quipping that “we conveniently have federal elections immediately preceding these panels so we have something to talk about every two years.”

Here are their insights:

First, a primer on “thermostatic voting”

Thermostatic voting is the idea that the electorate acts as a thermostat to balance the political climate, explained Baughman, an associate professor of politics whose specialty is American politics and the U.S. Congress.

“If your house is too cold, the thermostat triggers heat” to bring the temperature back to normal. “Often, the electorate in a mid-year election will pull the government back to the ideological center. So after a Republican president is elected, swing voters may want to elect more Democrats in the midterms to check the president.”

The lack of a “red wave” doesn’t mean there was no thermostatic voting in the 2022 midterms

Pundits expected that thermostatic voting would create a “red wave” of Republican victories during the midterm elections. “Those expectations came from President Biden’s low approval ratings and past midterm results,” Baughman said.

“But leading up to the election, pundits misapplied” the idea of thermostatic voting.

Typically, thermostatic voting reacts to what the president is doing that dominates the headlines. But Biden didn’t change the temperature of the electorate. Something else did.

Baughman asked the audience to think of the biggest policy change over the past year. “It’s probably not what the president did. It was arguably the Dobbs decision, overturning Roe v. Wade,” he said. “There’s quite a bit of evidence, especially in states like Michigan, that voters were responding with a thermostatic reaction to Dobbs more than to Biden’s low approval rating. This benefited Democrats. It was a reaction against a conservative Supreme Court.”

Baughman added, “It’s extraordinarily rare for a Supreme Court case to generate the level of public reaction that we had in this case. I can’t think of a similar moment in modern American history.”

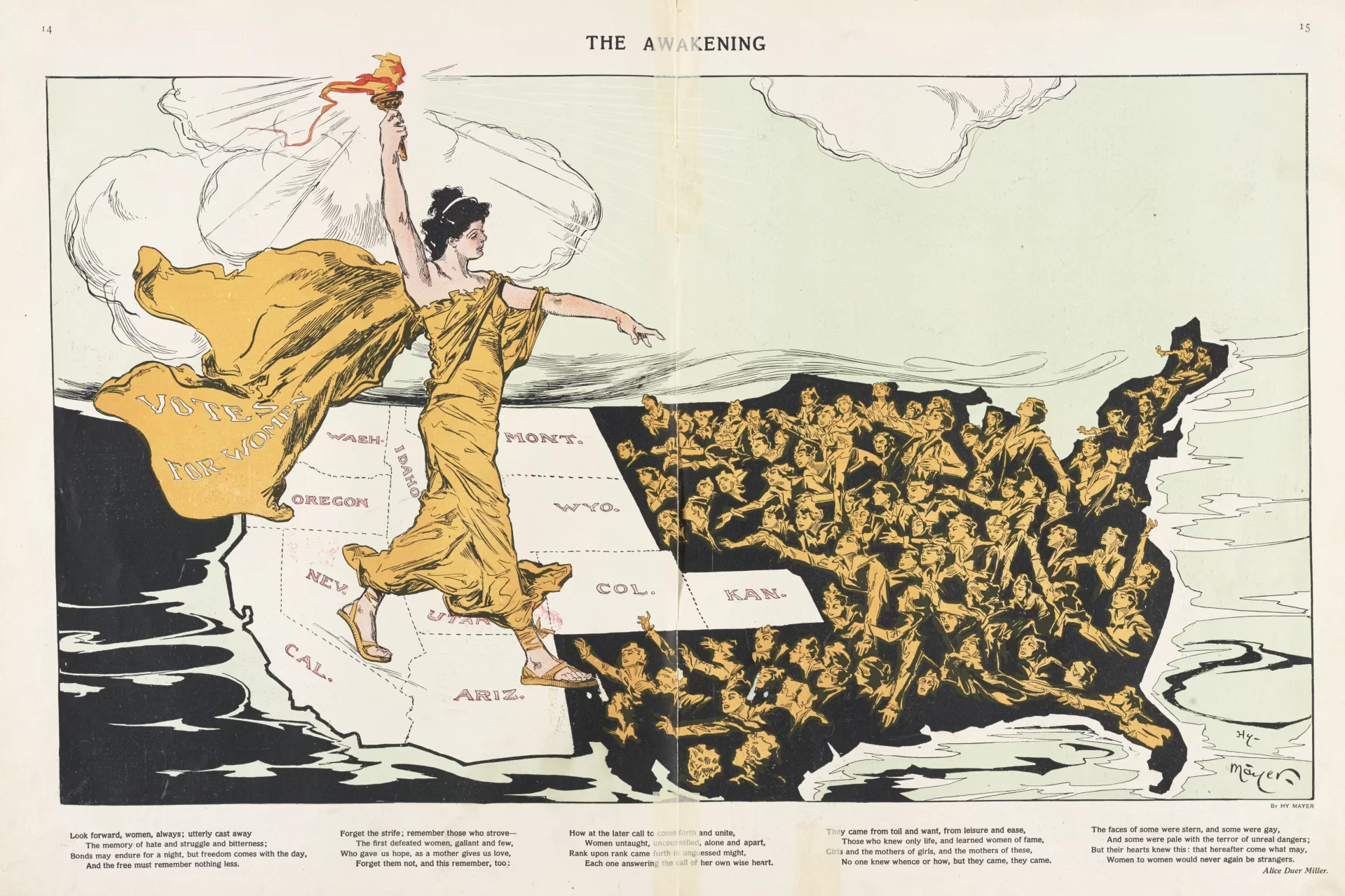

Young voter turnout played a big role in the midterms

Pavel Bačovský is a visiting assistant professor in politics whose specialty is political behavior, including youth political behavior.

Noting that “everyone’s probably most interested in the turnout,” he cited data from the CIRCLE at Tufts University, which defines voters between 18 and 29 as “youth.”

“We see that the turnout this year among young voters was 27 percent, the second highest in the past 30 years — nothing to sneeze at,” he said. “It’s less than the last midterms in 2018 where it was the highest in the past 30 years at 30 percent.”

The issue that young voters prioritized, said Bačovský, was a woman’s right to choose. “Forty-four percent of young voters prioritized” a woman’s right to choose. “And the overwhelming majority of them trust Democrats more on this issue than Republicans.”

He added, “Inflation was their second-highest issue, 21 percent. And even in older demographics, abortion was the still the second-most important topic, behind inflation. So absolutely: This was a situation where the electorate, especially the young electorate, has gone for a party that they think would protect the women’s right to choose.”

SCOTUS doesn’t care ’bout elections

In terms of the Supreme Court, “I don’t think that the election results will matter that much,” said Engel, professor of politics and associate dean of the faculty who specializes in constitutional law, judicial politics, LGBTQ politics, and U.S. political development.

”I don’t think the election actually changes their calculus in any way. The court will still be taking on considerations of race and higher education. It will still be taking on a key case regarding the tension between the First Amendment and same-sex marriage.”

In fact, he said, “the court seems pretty unconcerned with the decline of its own institutional legitimacy, as measured in public polling in the wake of Dobbs. They don’t seem to particularly care about this right now.

The Democrats might not lean into abortion rights issue for political gain

Despite voters siding with Democrats on abortion access, said Engel, “I don’t expect Democrats to lean into this in a political way that might parallel, for example, the way Republicans kept putting bans on same-sex marriage on the ballot in 2004, 2006, and 2008 as a kind of get-out-the-vote mechanism. I don’t think Democrats have the bandwidth or the stomach to do that.”

Republicans did not tell voters what they would get

Engel pointed to a public scholarship essay by Julia Azari, where she argues that Republicans failed to tell voters what they would get if they put Republicans in power.

“The only thing that people knew they would get was probably some kind of anti-abortion access policy,” Engel said. “And that was clearly rejected by the voters.”

Which is not surprising. “If you had followed public opinion polling on abortion access, it’s not surprising to me that the American public rejected restrictions on abortion access that were on the ballot.”

Codification of same-sex marriage doesn’t make sense from a constitutional perspective

Led by Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer, the Senate is taking steps to protect same-sex and interracial marriages through federal law.

“As a constitutional scholar, I do not understand this strategy or what it accomplishes,” said Engel. “As political optics, I get it. It pushes Republicans into the uncomfortable position of hating on same-sex marriage, which now has overwhelming public support. It pushes Republicans into dealing with the fallout of Dobbs, which they clearly do not want to do.”

But any federal law, Engels points out, “can still be held by the Supreme Court to be unconstitutional. So if the court really wanted to overturn Obergefell [the SCOTUS case that requires states to issue marriage licenses to same-sex couples and to recognize same-sex marriages], a federal law codifying Obergefell does not stand in their way.”

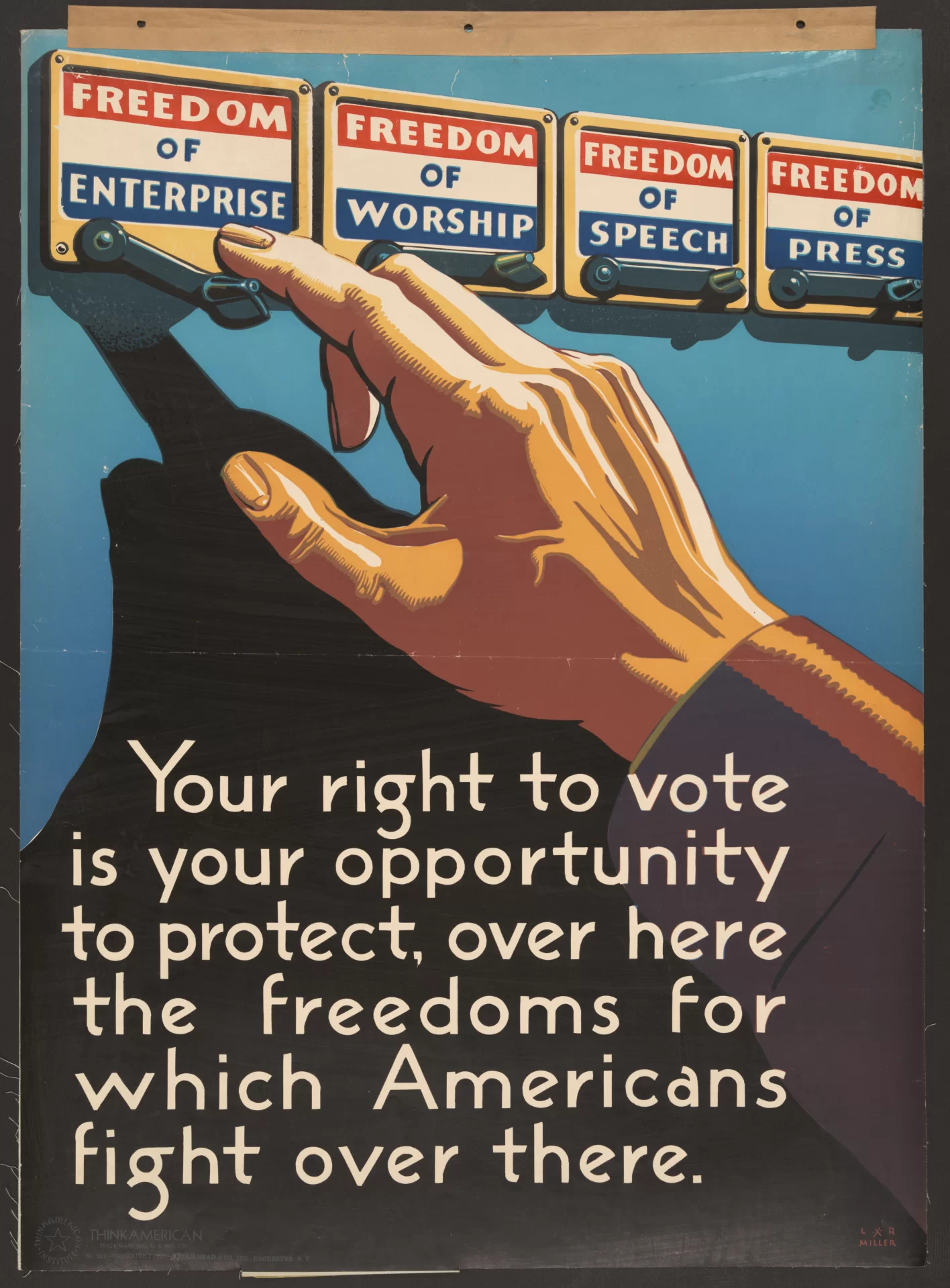

It’s not a good look for a candidate to encourage election denying

In its reporting, the news media has agreed that denying election results is not a winning strategy for political candidates and that voters overwhelmingly rejected election deniers.

“I think that that’s right to a certain extent, but there’s more,” said Lisa Gilson, an assistant professor of politics who specializes in political theory, particularly theories of protest and criticism, and who also teaches the politics of the American far right.

“It’s significant that the overwhelming majority of the election deniers who were running for secretary of state, the office that administers and validates elections, lost their elections, which suggests that voters, or at least most voters, do not want the people who are supposed to be certifying the election to be denying the validity of these elections.”

One of the reasons why election denying didn’t work, said Gilson, pointing to a recent article in The New York Times, is because it “reduces the turnout of voters who were concerned about or were buying into conspiracy theories about voter fraud.”

Telling voters that their vote isn’t going to be counted “is not actually a really good strategy to get people out to vote. Those voters tend to be disillusioned with the whole process anyway, so you’re actually turning away voters.”

2024 looks good for the Republicans

2024 could be tough for Democrats in Congress, Gilson believes, because Democratic incumbents are vulnerable in a number of Senate elections in 2024, including West Virginia, Montana, and Ohio. “These are states that are red or Republican-leaning.”

And Democrats will have few opportunities to pick up seats in Congress. “Maybe in the past we used to think that Florida was a state that you could potentially pick up,” Gilson said. “It’s not anymore; Florida is very red. Texas, too, hasn’t worked out well recently for the Democrats.”

Then there’s the issue of various states, including Ohio and North Carolina, engaging in redistricting of congressional districts. “The midterms were run on maps that are relatively favorable to Democrats. And they have been in the process of redistricting,” which may not favor Democrats.

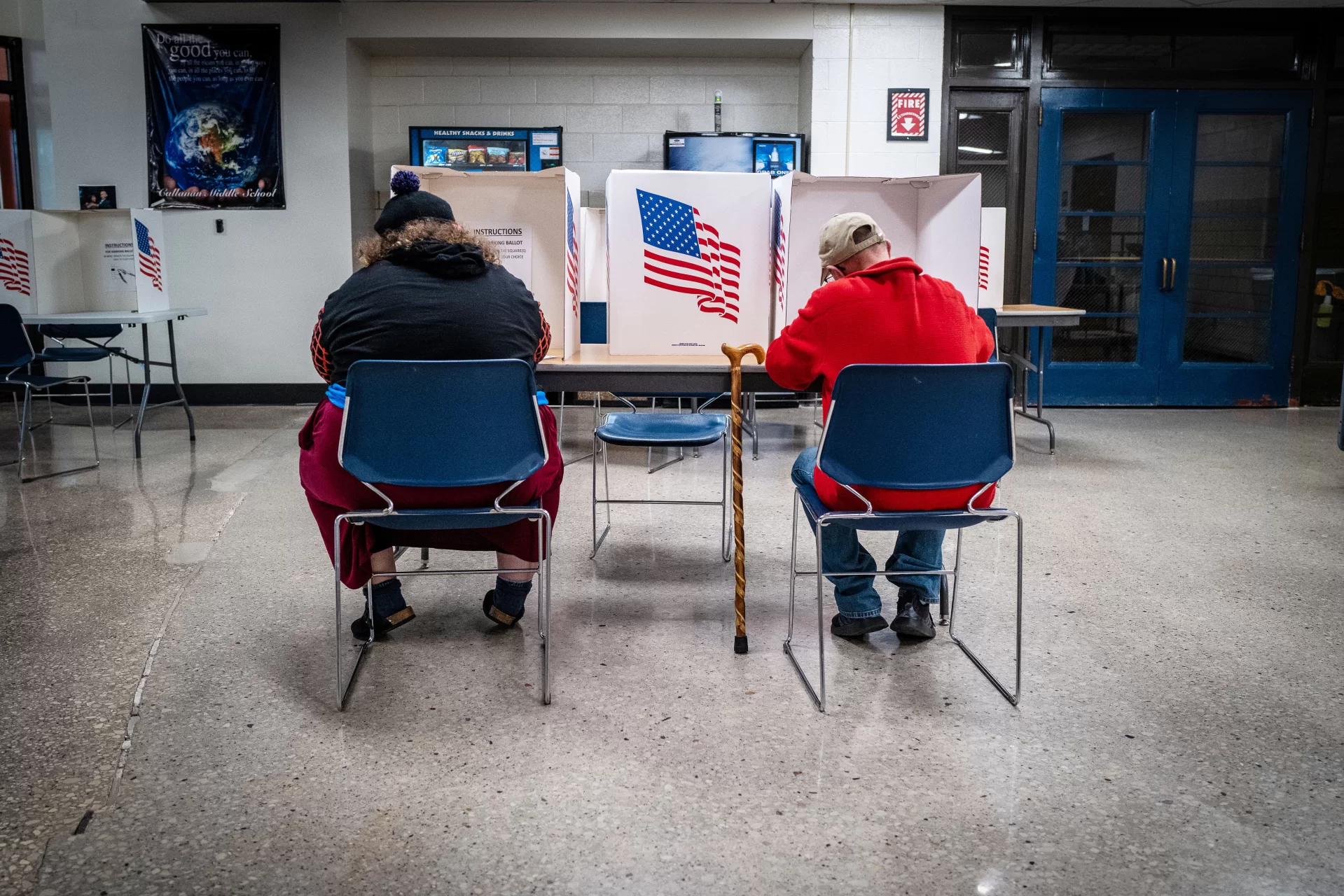

Elections are about counting, not voting

“Elections are not just about the voting but about counting,” said Chris Price, a visiting assistant professor of politics, giving a nod to playwright Tom Stoppard’s line.

Price, who specializes in contentious and violent politics, used the quote to give meaning to the fact that “68 percent of Americans said that they believe that the status of democracy in America was either somewhat or very insecure.” And if such a large percentage of the electorate believes elections and democracy are insecure, that opens the door to a “potentially violent challenge,” he said.

Price is part of a team, which includes colleagues from the University of Chicago’s Project on Security and Threats, that has been trying to measure the “potential mobilizable base of people who say that the election in 2020 was rigged and that they would be willing to endorse force to overthrow the presidency.”

His group “estimates that at about 8 percent” of Americans who, under the right conditions, would be “more than willing to use violence to get their preferred political outcomes.”

So far, bad attitudes have not yielded widespread violent behavior, he says. “But in the run-up to this set of elections, we did see some more very worrying, observable things,” including the armed intrusion into House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s house.

In Arizona, “armed individuals wearing tactical face masks were watching ballot boxes in the run-up to the election. While these are all worrying signs for now, I have to say, so far, so good and knock on wood.”

What will the Republicans rally around in 2024?

“One of the questions going forward about the Republican Party is whether it’s going to coalesce around a coherent fiscal policy,” said Gilson.

It’s speculation, she offered, “but one of the Republicans’ difficulties is that voters may be partial to Trump, they want to decrease the debt, and they also want to expand Medicare. They want all different things at the same time.”

In 2024, “will the Republicans have a coherent platform on fiscal issues? Will one even be necessary? It should be, because even if the rate of inflation is decreasing by 2024, we are still going to be dealing with economic fallout.”

Trump announcing his candidacy doesn’t shield him from various investigations, but…

Trump’s official candidacy for president “doesn’t provide him any kind of immunity” from prosecution, said Engel. “But again, optically it looks weird for the Department of Justice to be investigating an announced presidential candidate.”

Baughman suggested that observers watch to see if Republicans begin indicating support for the investigations. “If Republican leaders really do want to take Trump off the board, they can embrace the investigations, or at least no longer voice the objections they’ve been voicing. That’s one thing to watch for: Does [U.S. Attorney General Merrick] Garland tacitly or even openly gain more support from Republicans?”

If Trump doesn’t win the Republican nomination, might he pull a “Teddy Rooseveltian Thing”

“The former president is the nominal leader of the party, but Trump doesn’t care about the Republican party,” Engels says. “It’s not an apropos analogy, but if he doesn’t win the nomination, will he pull a Teddy Rooseveltian kind of thing — ‘I’m gonna break off, run independently, and bring my voters with me’?”

In other words, said Engel, “it’s not clear to me that the Republican party can deal with Trump if Trump is not the nominee.”