Art and activism, the theme of this year’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day observance at Bates, could be expressed visually in a serious and heavy way.

“But Blackness is much more than that,” says Olivia Orr, a graphic designer in the Bates Communications Office who designed two distinctive posters for this year’s observance. “Blackness is beautiful, it’s bright. And the history of MLK is beautiful. We can celebrate — we’re allowed to be joyful and artistic and expressive.”

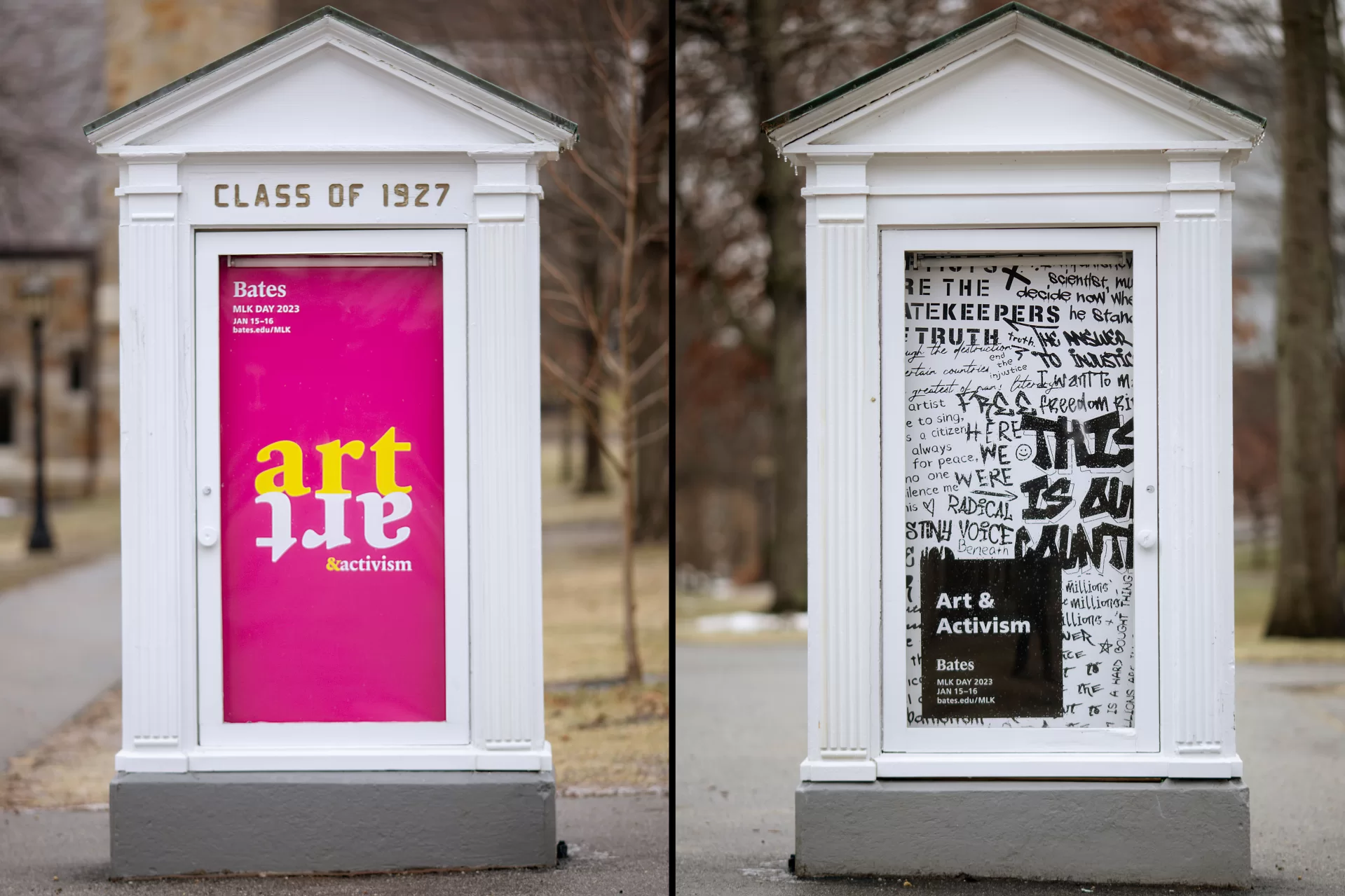

Evoking all three elements, the poster designs are now displayed everywhere on campus, from the historic “Mouthpiece” outside Hathorn to the many widescreen monitors within Bates buildings. One poster is black and white, featuring a slew of uplifting quotes about the power of art and activism, rendered in different fonts to suggest different voices.

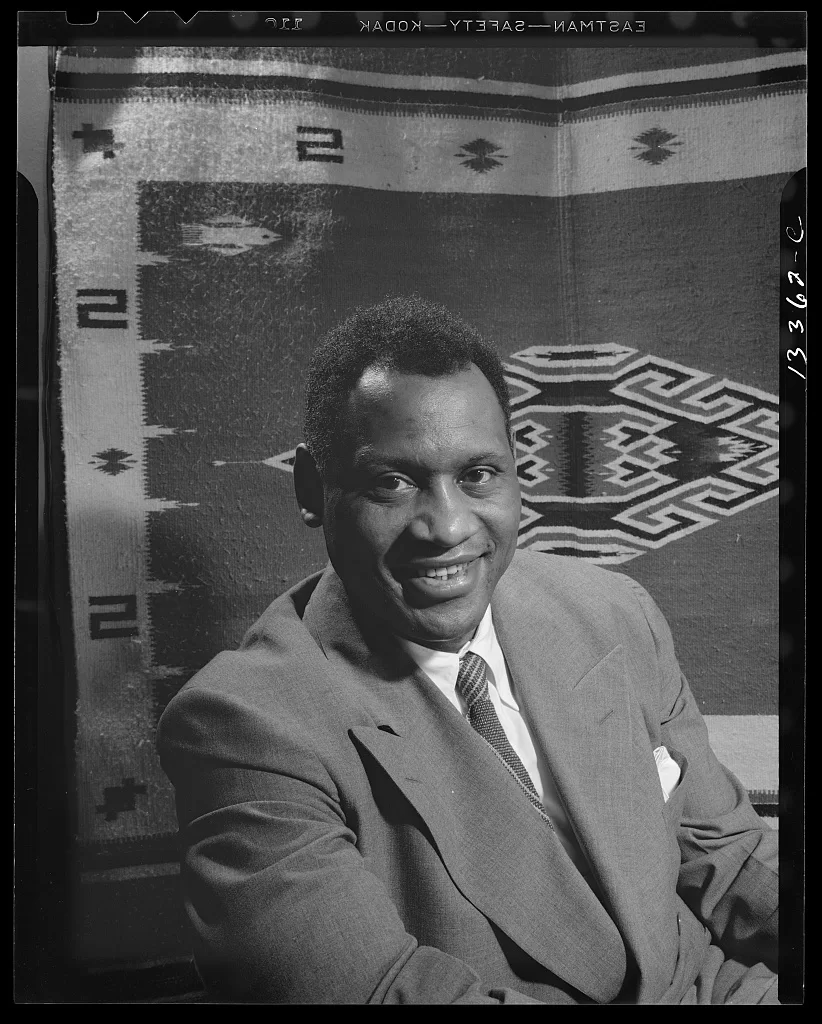

The quotes, such as “Artists are the gatekeepers of truth” and “No one can silence me in this,” are all attributed to an iconic 20th-century figure who embodied the intersection of art and activism: Paul Robeson, an actor, athlete, singer, and activist, and one of the most important voices in the Harlem Renaissance.

The second poster is bold and colorful: magenta, yellow, and white. The text is minimal, just “art & activism.” The word “art” is rendered two ways, rightside up and upside down. The meaning? “It’s just art,” says Orr.

During a meeting of a subcommittee of the MLK Day Planning Committee, the group talked about their ideas for this year’s poster. Committee member Phyllis Graber Jensen, director of photography and video for the Bates Communications Office, shared a link to an American Masters web page featuring quotes from Robeson, who was featured by the PBS documentary series in 1999.

Graber Jensen suggested that his voice and story might inform a poster design. For designer Olivia Orr, Robeson’s was a new name, but after doing more digging, she was captivated by his story and his words. “He was radical and anti-colonial. And he spoke the truth of that publicly.”

Robeson was blacklisted in the 1950s, his passport taken away. He was unable to work for eight years, until a Supreme Court ruling forced the government to reinstate it. “I have to imagine that in some ways, it made his voice stronger,” Orr says, “because of the way it brought attention to the fact that he was being silenced.”

For Orr, it was refreshing to learn about a radical figure like Robeson and to share his words and voice. When it comes to the civil rights era, “society tends to focus on the same people again and again and again,” she notes. Society also tends to sanitize their radical ideas, including King’s, which makes them feel “not quite so controversial any more” to a contemporary audience — “at least the parts that we talk about are not controversial.”

Orr, who is involved in different activist organizations and efforts in Portland, where she lives, blends art and activism in her own way. Artists, herself included, “can sometimes feel a responsibility to tell the truth with their art and to be honest, like their work comes from a place of honesty.”

“Their art also can speak the truth about the world, about the situation that they’re in, and I view that responsibility as a heavy weight that artists carry. They’re telling the truth and being honest and they have a chance to show a larger audience their work.”