Matt Tavares ’97 has been writing and illustrating children’s picture books for more than 25 years. He’s a serious, established artist and author, with the awards and glowing reviews to show for it.

Kirkus Reviews has called his illustrations “magisterial.” The Washington Post has raved about how gorgeous his work is. His 2019 picture book Dasher has had multiple appearances on The New York Times bestseller list, including as a seasonal release again in 2022.

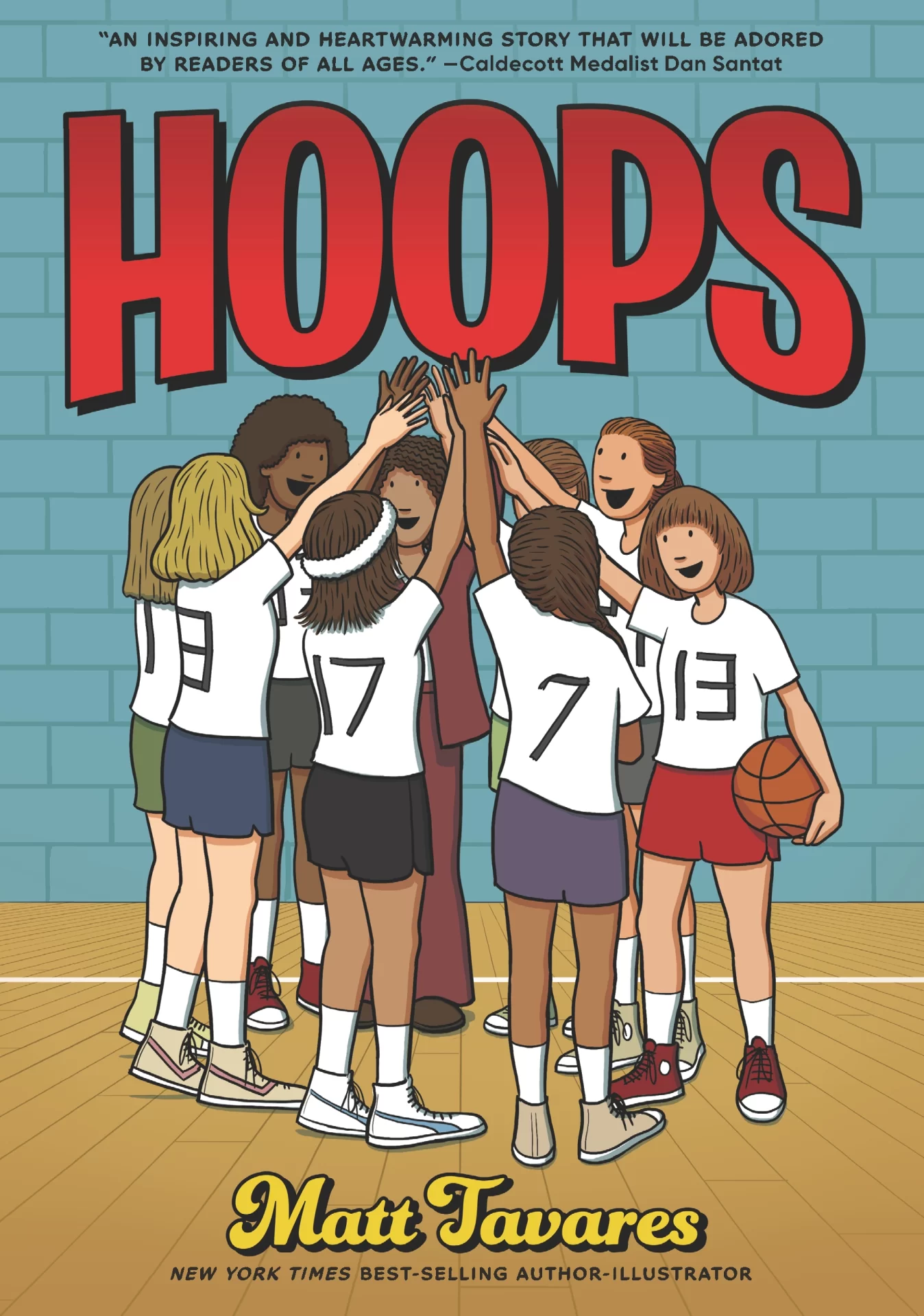

But his latest book, Hoops, published this month after nearly seven years in the making, challenged Tavares like no other. Hoops is historical fiction inspired by the true story of a high school girls basketball team from Warsaw, Ind., that had a Cinderella season not long after the 1972 enactment of Title IX.

It’s a graphic novel, a genre Tavares has long admired but never tackled before, and it has, conservatively, 20 times as much artwork as he is used to producing.

Picture books, his usual medium, are typically only 32 pages long, and often, there might be a single drawing or painting that covers two of those pages at a time. Hoops is 224 pages long and as with most graphic novels, often has several frames on a single page. That meant Tavares had to generate a lot of art. “Probably like a thousand pictures,” Tavares says.

There’s nothing boastful in his tone (but with Tavares you get the sense, instantly, that he’s never going to be a boaster). It’s more like a seasoned marathoner telling you about their first 100-mile run. You know they prepared for it and they wanted to do it, and yet still, it was grueling. And maybe on some level, even they can’t believe they got through it.

“Definitely there were some days where it felt sort of scary and terrifying that I didn’t know what I was doing,” Tavares says, sitting in his kitchen in the southern Maine town of Ogunquit. It’s a late summer day, and he is in the final proofreading phase with Candlewick Press, his longtime publisher, for Hoops, slated to arrive close on the heels of the 50th anniversary of Title IX. “I feel like I’ve been doing picture books for a long time, and I love making picture books, but this was like, this…”

His voice trails off as he ponders how hard the process was but if you filled the space the words might be: Really. Hard. Thing. “I almost couldn’t believe they were letting me do this,” Tavares says. “Like, I have a family to support, this needs to be good.”

“Two hundred-plus pages of all artwork,” says his friend and fellow children’s book author, Chris Van Dusen (author of picture books like The Circus Ship and Down to the Sea with Mr. Magee). “It is just crazy. But he is passionate about his artwork and this story. I kept saying, ‘You are a better man than I.’”

Tavares didn’t start the project with intentions to make a graphic novel. But he wanted to do justice to an important story, one about gender equality in sports. In 2016, when he first learned about the 1976 Warsaw Tigers, he’d been spending “countless hours” watching his two young daughters, Ava, now at Bentley College, and Molly, now at Wells High School, play basketball. “It was definitely something that felt personal to me,” he says.

He’d discovered the Tigers and their star player, Judi Warren, in the pages of the National Book Award finalist We Were There, Too! Young People in U.S. History, by Phillip Hoose. In the early 1970s, “most schools had sports programs for boys but very little to offer girls,” Hoose writes in the 2001 book. Basketball-crazy Indiana had its huge statewide high school basketball tournament, made famous by the 1986 movie Hoosiers — but just for boys. It wasn’t until 1975, by coincidence the year Tavares was born, that the impacts of Title IX permeated Indiana to the point where a statewide competition for girls basketball was considered a necessity.

Even then, at Warsaw High, the girls team was hardly a priority. The “Lady Tigers” had neither uniforms nor a bus to take them to games. They had to practice at the grade school (at dinner time), and when they asked the boys’ basketball coach for equal access to the gym, he told them they’d have to be able to fill the gym with fans for that to happen. Then they went on to (spoiler alert) win the state championship.

With Hoose’s blessing, Tavares contacted and interviewed Judi Warren, and through her, several of her Tigers teammates. Their stories felt rich, filled with details and a thread of persistence and true love of the sport.

Tavares’ work in general tends to the historical and biographical, with a speciality in origin stories. In Growing Up Pedro, he told the story of Pedro Martinez’ journey from the Dominican Republic to baseball’s Hall of Fame. In Henry Aaron’s Dream, readers learn about Aaron’s childhood in Alabama, through his time in the Negro Leagues to his Major League Baseball debut. He illustrated a book about the vision for and completion of the Statue of Liberty and wrote and illustrated another about the Great Blondin, the 19th-century tightrope walker who crossed Niagara Falls.

“What makes Matt great is how true to himself he is in his work. He puts himself into every page.”

Mo Willems

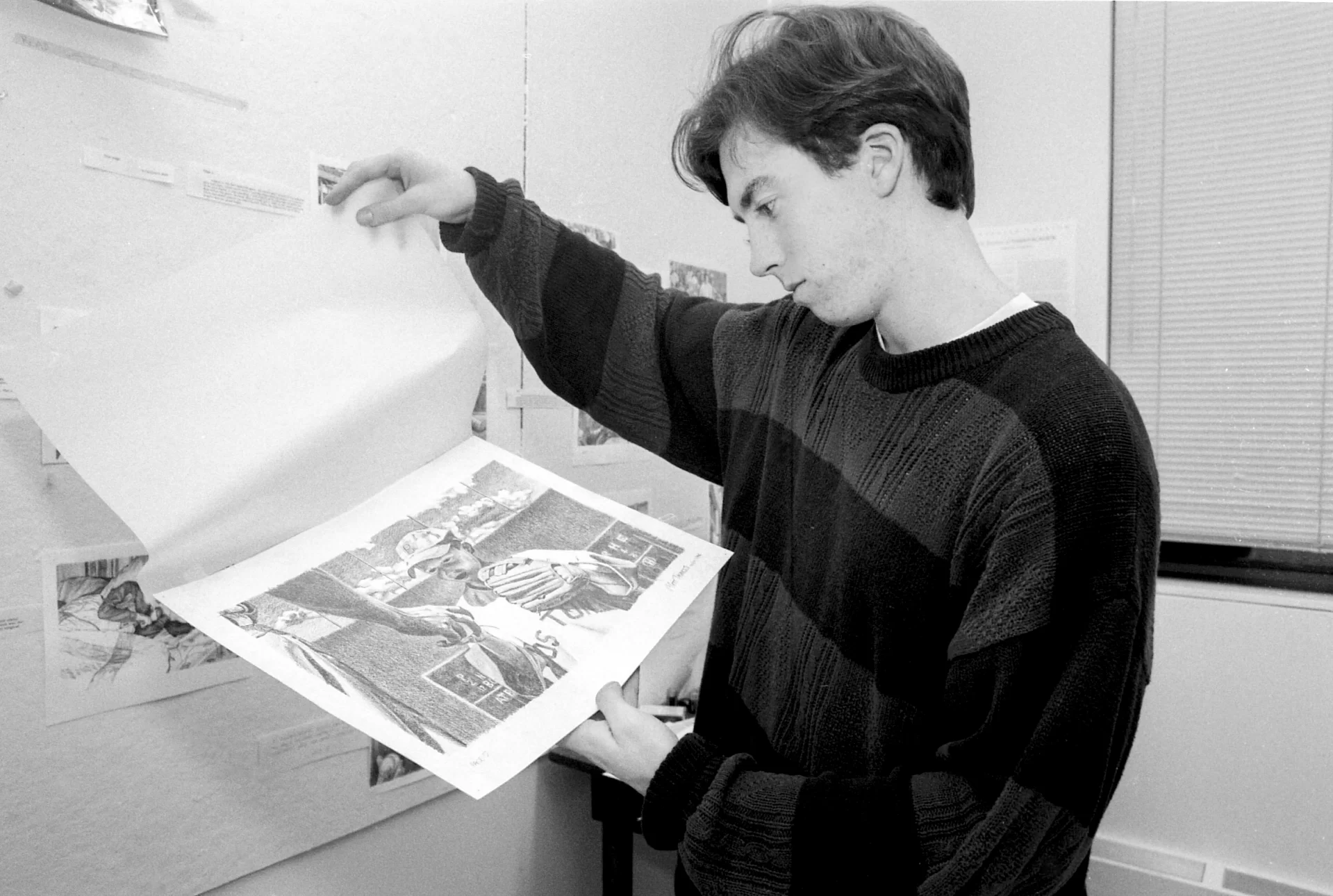

Tavares’ first book was Zachary’s Ball, published in 2000. A revised version of his Bates studio art senior thesis, the book became a regional sensation, chosen by the Boston Red Sox for a reading day event and named one of the 100 classic New England children’s books by Yankee magazine. He has written and illustrated nine more of his own books, along with illustrating a dozen more authors. They’re all intimate works, every face and detail lovingly conceived of and executed.

“Matt’s work is great not because of the detail or the research or the compositions that he creates,” says Mo Willems, the author of such treasured children’s series as Knuffle Bunny and Elephant and Piggie. “Those are the things that make him good. What makes Matt great is how true to himself he is in his work. He puts himself into every page.”

By 2018, two years into the project, Tavares realized he needed more pages for Hoops. “The story he had in mind really suited a longer format,” says his friend Ryan T. Higgins, a Maine author who Tavares mentored when he was still at the self-publishing stage (today Higgins is a New York Times bestseller, five volumes into his Mother Bruce series). Higgins and other writers in their friend group encouraged Tavares to try a graphic novel.

Tavares was already seriously intrigued by the genre, especially by the way his daughters Ava and Molly were reading them. “Just devouring them, and then reading them again.” In his childhood, the only graphic novels were essentially comic books, and looked upon as some lower form of literature. Now they were widely respected and they could also reach a broader audience, appealing to older and younger kids.

But how to go about it? He read and reread Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud. With the word balloons and timestamps and multiple panels per page, he decided he needed to change his artistic approach.

“I felt like the art needs to focus more on clarity and just simplicity. Just tell the story and get the information across. As opposed to in my picture book art, where I would try to get into every little detail and make, you know, fully rendered paintings. Logistically, I knew, if I’m ever going to finish this book, I have to figure out a simpler process.” He threw away countless sketches of Judi, his main character, as he pared down the imagery.

“You have to redraw the same character a couple of hundred times, and it’s a matter of figuring out, what do the characters look like? What shape are the faces? What are the eyes? Are they going to be dots? There’s so much personality in those simple lines. To be able to express a full range of emotions with just a few lines is in a lot of ways more powerful.”

Tavares looked at the work of colleagues, like that of Willems, a multiple Caldecott and Emmy winner, and considered how much simple, seemingly quick sketches could convey. They’ve swapped art in the past, and two of Willems’ Elephant and Piggie sketches hang in Tavares’ house in Ogunquit while an original drawing from Tavares’ Lady Liberty hangs at Willems’ house, part of a “who’s who of contemporary illustrators as a reminder for me to do my best and be my most authentic,” Willems says.

“More people might connect with Elephant and Piggie [as they are] than if they were a specific, realistically drawn human character,” Tavares says. “That’s something that kind of took a while to get through my head. Now I look at these little cartoon characters I drew for Hoops and I feel like I get across all the information I would want to get across, but it’s just kind of boiled down to its essence.”

Tavares found creative joy in the graphic novel format of Hoops: He had much more space to develop the characters. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Along with the stylistic change, he was making a digital leap. A few years before, Higgins had given him a high-tech hand-me-down that would turn out to be a vital tool in his creative process, a Wacom drawing tablet. “A number of people had suggested digital artwork to him,” Higgins says. “I think I was the one who was most persistent. I like the idea of Matt trying new things. His traditional art work is so intricate and lifelike. I just know how long that artwork takes him.”

When they first met, about a decade ago, Higgins was selling self-published books out of the back of his car. “It was at a very important time in my life where I needed to see someone who did that job on a very successful level,” he says, joking that he latched onto Tavares. “I drew a lot of inspiration from him. When I had a book that I wanted to present to publishers, he was the one that really helped me navigate that.”

So he was more than happy to teach Tavares how to use the Wacom. And working digitally has been revelatory for Tavares. In his home studio, tucked behind the family’s living room, Tavares pulls up a few pages from Hoops onto the screen to show how the Wacom works (he’s since upgraded from the one Higgins gave him). “I can do all these amazing things that I can’t do on a piece of paper.” Like move faster, and more nimbly.

Working digitally on a Wacom tablet lets Tavares do “all these amazing things that I can’t do on a piece of paper.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

He grabs a copy of 2022’s Twenty One Steps: Guarding the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, which he illustrated for author Jeff Gottesfeld. “I drew the soldier on one piece of paper and I drew the background on a different piece. Then I scan them in. If it’s all on one piece of paper, I can’t move the soldier unless I start over.” The Wacom gives him the digital freedom to play around. While tackling this new genre for Hoops, that leeway was essential.

“It was great to see him get into it,” Higgins recalled. “He just sort of lit up and had this fire to him.”

“When I try something new, it’s like my brain awakens,” Tavares says.

Part of Tavares’ joy was the gift of more space to develop the characters in Hoops. While he changed some of the timeline of the Warsaw Tigers story, he used much of what he learned from those conversations with Judi Warren and her two close teammates as inspiration. For instance, their real-life quirky pre-practice habit landed in Hoops. “They would all eat baby food before practice,” Tavares says. “It was like something they could eat that wouldn’t make them feel sick. And it just turned into like this fun, just weird thing that high school kids do, you know?”

He cherishes some of the quieter moments he illustrated, as when Cindy, Judi’s best friend, starts dating someone. “And all of a sudden Judi’s alone after school. And I just remember illustrating that scene where I can show her bored and just kind of annoyed. It was so cool to be able to just take that time, to get into those little quiet moments.”

It’s now been 25 years since Tavares had his last formal art instruction, at Bates, where he took “fundamental art classes,” courses in drawing, painting, sculpting, and color theory. After graduation, he moved into self-teaching mode, revising his thesis project, which was black and white, getting feedback from art directors, and, after Candlewick bought Zachary’s Ball, continuing in that vein. “I learned a lot just by doing,” he says. The five Lupine Awards, the Maine Library Association’s highest honor for children’s book authors, hanging on his studio wall are a testament to how well he’s taught himself.

As he goes, he’s working through a short list of professional goals. One was to make The New York Times bestseller list. “Like one week,” Tavares says. “Just get on there.” Dasher, the story of a young reindeer who escapes from a traveling circus with dreams of finding Santa and the North Pole, took him there on multiple weeks, climbing as high as the No. 3 spot on the children’s list. “So that was pretty amazing, just to get that call from my editor.” (A sequel is in the works.)

Another is to win a Caldecott honor (the American Library Association prize for excellence in children’s books). “Like, I don’t want the gold,” he says, smiling. “Just at least a silver one. One time.” Higgins says his friend also quietly aspires to have a truly iconic holiday picture book, in a similar vein as The Polar Express. Higgins believes Tavares will get there. “I think Dasher will end up being like The Polar Express,” he says.

Taped to the wall in a corner of Tavares’ studio is a testimonial from another loyal fan. It’s a list created by his daughter Ava when she was a pre-teen, titled “Top 10 Reasons You Are the Best.” It’s worth noting that four out of the 10 listed are book-related.

You make fabulous books.

You let my family be the first people to see your new books.

You teach me how to draw.

You are the best children’s book author and illustrator.