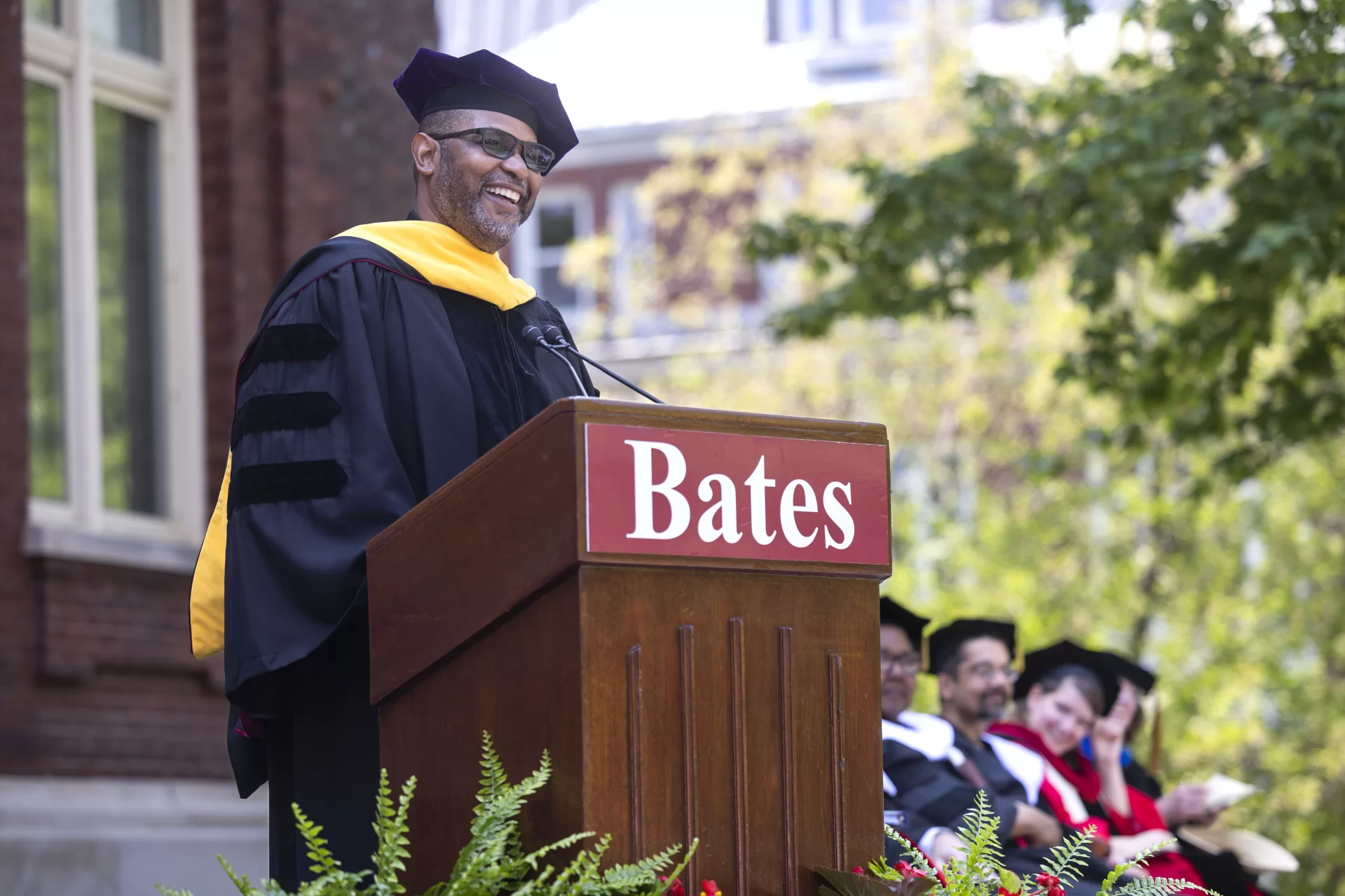

Had Benjamin Mays not ventured north to Bates to seek self-emancipation more than a century ago, Sunday’s graduation ceremonies would have looked much different, said Bates Commencement speaker J. Drew Lanham.

The thought dawned on him this very morning, Lanham said. A world without Mays, the 1920 Bates graduate known as the Schoolmaster of the Moment for mentoring Martin Luther King Jr., would today likely be a “world where I am not standing here now,” said Lanham, a scholar, author, and self-described “bird-loving Black kid” who grew up in South Carolina.

Invoking Mays was a crowd-pleasing moment during Sunday’s graduation, which saw degrees conferred on 439 graduates who gathered in front of Coram Library with family and friends and Bates professors and staff on a warm, sunny morning.

But the nod to Mays was more than just a gesture; it was a central part of Lanham’s message about how we should live our lives with a shared pursuit of freedom and a full-circle mindset: “360-degrees around, beginning to end, me to you, and all that we connect to, every azimuth and degree in between, person to person, stranger to friend.”

The complete video of Bates Commencement on May 28, 2023

At Sunday’s ceremony, Lanham, who holds the Alumni Distinguished Professorship in Wildlife Ecology at Clemson University and is the author of The Home Place: Memoirs of a Colored Man’s Love Affair with Nature, also received an honorary degree. He was praised in the degree citation as “expert on birds and an artist with words — dedicated to the proposition that the natural world we all inhabit is meant to be experienced fully and joyfully by all people — despite the barriers that too often prevent this.”

Lanham was joined by fellow honorands Michael Lewis, the award-winning author of such books as The Big Short, The Blind Side, and Moneyball; Julieanna Richardson, founder and executive director of The HistoryMakers, the preeminent archive of African American oral histories; and Shankar Vedantam, who is renowned for his Hidden Brain podcast and radio series.

This year’s 439 graduates represent 39 U.S. states and the District of Columbia and 38 countries. Eleven percent are the first in their family to graduate from college, and 44 percent studied abroad. Twenty-six seniors earned departmental honors for their senior thesis, and three seniors completed two honors theses each. Among the graduates, 47.2 percent were varsity athletes.

What’s next?

Only seven of the college’s 157 commencements have been hosted by a president in their final year in office, and this was one of them, as Clayton Spencer will step down as the college’s eighth president on June 30.

In her welcoming remarks, Spencer acknowledged the connection that she and the Class of 2023 have, both heading out into something new and/or unknown.

“Everyone I run into has the same question: ‘What’s next for you?’” Spencer said. And like a senior being quizzed about their next step but not having a snappy answer, Spencer said she got “kind of stressed and a little irritated” that everyone seemed to expect that the outgoing Bates president surely would be ready for her next act, even after running a college for 11 years, a stretch that included a global pandemic. “Don’t I get to just do nothing for maybe a summer?” she asked.

From a practical standpoint, Spencer suggested that “I’ve got a few irons in the fire” is often “sufficiently vague to deter the over-eager questioner.”

But in terms of the larger question, should a senior (or even Spencer) feel that they should have their life all figured out? “Emphatically, ‘No,’” she told the seniors.

“As you face the blank canvas of your 20s… resist the temptation to panic and grab for premature clarity or a narrative that sounds impressive…but really isn’t you,” Spencer said. “If you pause and look within yourself, I’m pretty sure you will find the confidence and patience to take things one step at a time and build your way toward your own true version of a life of meaning and purpose.”

Every step forward, however small or seemingly insignificant, “is a step you will learn from,” she said. “You will learn practical skills — like how to drag yourself out of bed in the morning and get suited up for work, or how to eat healthy meals when you can’t just swipe into Commons.”

There will be existential lessons, “like how to deal with difficult housemates or colleagues, how to cope with not being valued in a space, or not seen at all. You may learn, as well, that whatever you’re doing at any given moment is the farthest thing from what you want to do with your life. And the great news is, in the decade of your 20s, there is plenty of time for do-overs and re-invention.”

For the record, Spencer has shaken 3,728 hands at Commencements since 2013, with virtual 2020 (no handshakes) and mostly-no-shake 2021 cutting into the total. The first graduate she congratulated, in 2013, was Hakimah Abdul-Fattah ’13, Fulbright winner and now a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Pennsylvania. The final handshake today was with Leah Zukosky of St. Louis.

‘One of your own is our own’

Lanham started his address by expressing gratitude for the honor of being a Commencement speaker and honorary degree recipient, that “you would honor me, my family, and a long line of ancestors who worked, who toiled for hundreds of years by force and not choice for this moment.

“Their bitter sacrifice leads me to this sweetness, a bird-loving black kid with maternal roots and shoots in a little known and seldom seen place called Ninety Six, S.C.”

“Ninety Six Creek to the Androscoggin River. My Piedmont clay to your rocky shore. Full circle, Bates. I hope you’re beginning to feel that with me.”

Drew Lanham

The connection between Bates, Lanham, and Benjamin Mays has a nexus in that town, Ninety Six, where Mays himself was born and lived and was “my mama’s neighbor, a mile up the road,” Lanham said. Ninety Six “is where one of your own is our own.”

It’s all more than a coincidence, said Lanham. Mays, “a man who has come before me but whom I never knew but was close to me as family, speaks through me at this moment. Ninety Six Creek to the Androscoggin River. My Piedmont clay to your rocky shore. Full circle, Bates. I hope you’re beginning to feel that with me.”

For his theme and message, Lanham drew on one of Mays’ most famous statements. Bates, said Mays, “made it possible for me to emancipate myself, to accept with dignity my own worth as a free man,” a concept that is now baked into the Bates mission statement, which promises that Bates is dedicated to “the emancipating potential of the liberal arts.”

The emancipating potential of education, said Lanham, should teach us all that “what’s been done wrong should not be doubled down on by denial to repeat the sins again and again. That’s called ignorance. That’s the opposite of what you’ve been here to achieve. And so I know that what you will promote past this day is actually called education.”

At the same time, education means that “we don’t say what happened in the past and get over it. We acknowledge the truth to go forward. That is what I call critical fact theory,” to which the audience responded with a resounding cheer.

Freedom is “as an inalienable and emergent force, a seed inside each one of us waiting to burst forth and to grow.”

Drew Lanham

And if education has the power of self-emancipation and freedom, said Lanham, “the question that hangs out there then is, what does that freedom look like?”

For Lanham the ornithologist and naturalist, “it’s about wildness. It’s about finding these spaces unencumbered and untethered, where I can watch and not be watched to prosecutorial effect.” With wildness in mind, Lanham asked his audience to “think about freedom as an inalienable and emergent force, a seed inside each one of us waiting to burst forth and to grow.”

Thinking about freedom as an unalienable and emergent force, he said, means to “be able to look full on in the mirror without hesitation and love who is looking back. Freedom is that seed planted to form root and shoot, grown into a mighty oak. Freedom is that head and heart space that turns us loose to roam the hinterlands of our own imaginations.

“Freedom is head to heart to hand and back again. That is full circle, Bates. It is a place where discovery lurks around the hairpin turns on life’s path. Freedom is curiosity’s valve stuck on full flow.”

“Freedom is also about being shoulder to shoulder, together with me to be more than we can be alone.”

Drew Lanham

Freedom isn’t just reading banned books. “Freedom is reading a library full of them and then making sure those who would ban them get banned by vote from banning ever again,” he said, which prompted a round of applause. “Freedom is writing the book that others would ban if they could, but can’t.”

“Freedom is building the library where there is none. Freedom is leaving me alone to be who I am, dress how I want, control my body’s being without outside interference. Freedom is also about being shoulder to shoulder, together with me to be more than we can be alone.”

Lanham closed by asking the audience to embark on a shared mission, asking them to repeat a vow: “To be better, to do better, to bring my being, my community, the environment, humanity, and this world to better than it has been. To be an arc in the bigger circle. For without me, the circle cannot be.”

Senior Address

In his Senior Address, Rishi Madnani of Langhorne, Pa., gave a nod to Spencer by quipping, “Did we print Clayton a diploma?!”

Madnani used the metaphor of an in-vitro cell culture — controlled environments for growing cells — to describe the Bates community. “As incoming stem cells, each of us brought a unique genetic and molecular profile to the table: our similarities, and our differences, brought us together to form an impressively cohesive socio-cellular infrastructure.”

Assisting in this cultural development, “certain growth factors were added along the way: whether they were the intellectual stimulation of anthropology class, the timeless enjoyment of a cappella, or the vehement sense of purpose instilled in us through student government. These molecules activated signaling pathways which have helped us differentiate into the specialized cells that we are today.”

Making those reactions possible were enzymes: faculty and staff, who “served as biological catalysts without which life would never be possible.” (Getting a laugh, he added, “we also ingested a few molecules that aren’t exactly the best for growing cells, but I’d be lying if I said we didn’t create incredible memories along the way.”)

But even as the cells in a culture differentiate, “the sequence of the DNA in their nucleus remains the same — they never forget where they came from, and neither should we.”

For Madnani, his Indian heritage was his epigenetic signature, and early on at Bates, he missed the embrace of his culture. He considered transferring to a larger school with a larger South Asian population. “But before I sent in the application, I asked myself one question: what about the Brown kids that came to Bates after me? I knew then that I had to stay, and I’m so happy to be standing here today.”

Unlike a cell culture in a lab, however, the cells in the Bates culture were able to “influence the behavior of the experimenter watching over them” — in this case, the Bates administration — explaining how members of the senior class played a critical role in the successful creation of a course requirement focusing on race, power, privilege, and colonialism.

“As one of the first colleges in the nation to have such a requirement, our cell culture is constantly pushing the envelope and leading by example.”

What happens in a lab culture goes beyond a Petri dish, and what happens at Bates does not stay within the confines of campus. “Insights and discoveries that we yield from an in-vitro cell culture… are taken and applied on a larger scale,” including important drugs and therapies that we use today.

“While we may not have set the foundation for a revolutionary pharmaceutical compound, our trials and tribulations at Bates have allowed us all to make a number of discoveries about ourselves and our ability to make a difference in our communities.”

Honorary Degrees

In delivering this year’s honorary degree citations, Malcolm Hill, vice president for academic affairs, and dean of the faculty, noted that best-selling author Michael Lewis was an art history major. “Not a business or economics major, though he is perhaps best known for the books he has written about the world of high finance. Not a math major, though he has written about how statistics can win baseball games.”

He wrote a senior thesis on Donatello, the Italian sculptor. And as a writer, Lewis “sees the faces in the stone, and wields words like a chisel, bringing unknown — though real — characters vividly to life for our eager consumption, entertainment, and edification. His writing, in short, helps us better understand the world in which we live and think more deeply about how we move through it.”

Hill noted that Julieanna Richardson, founder and CEO of the HistoryMakers, shares a profound connection with Alain Locke, the father of the Harlem Renaissance, in their commitment to empowering Black voices and preserving cultural legacies.

Locke wrote, “Nothing is more galvanizing than the sense of a cultural past.” Richardson “frames a similar idea — the one that drives her immense contribution to the preservation of Black experiences in America — in this way. She says, “We want to reawaken memories, to reconstruct the history of a people who didn’t have time to capture it themselves.”

Shankar Vedantam is the visionary behind Hidden Brain podcast, which seeks to explore “the unconscious patterns that drive human behavior and questions that lie at the heart of our complex and changing world.” This requires the capacity, said Hill, to “very consciously observe the world around them — then process what they see, synthesize meaning, and communicate findings. In other words, the skilled investigator of the unconscious must wield the precision tools of the liberal arts. Vedantam “is a master of this craft.”