She’s 64 years old, but never ages. She’s a global phenomenon, switching careers like a pair of shoes. She has been lauded as empowering, and condemned for promoting an unrealistic body image. And now she’s on the big screen in a big way.

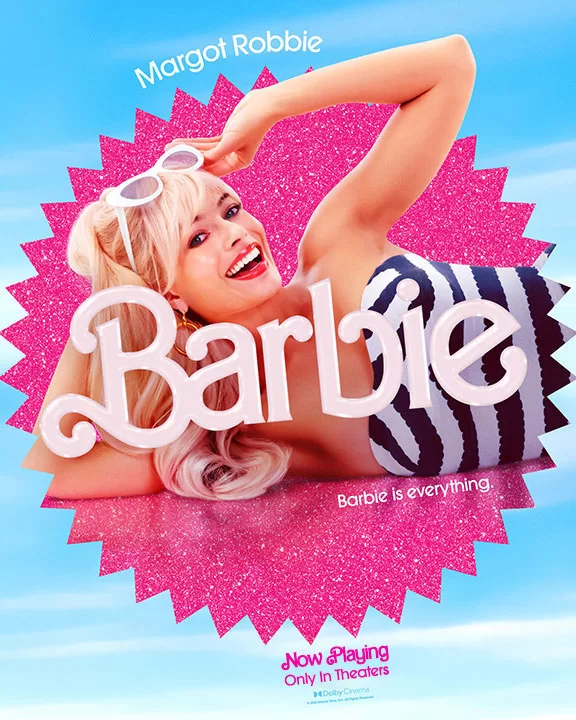

Since its July release, director Greta Gerwig’s Barbie has raked in more than $1.2 billion worldwide, making Gerwig the first solo female director with a billion-dollar movie.

We asked two Bates professors, Jon Cavallero and Erica Rand, to give us the lowdown on what’s up with the doll, from shelf to screen and everything in between, from their areas of expertise: Cavallero is an associate professor of rhetoric, film, and screen studies, and Rand is a professor of art and visual culture and gender and sexuality studies.

Rand has more than a passing interest in all things Barbie. In 1995, she published the book Barbie’s Queer Accessories, an examination of the doll, including its appropriation by children and adults using Barbie in very un-Mattel-authorized ways.

“One big ‘queers-come-hither’ moment in the trailer is when Barbie drives along in her Barbie convertible belting out ‘Closer to Fine’ by the Indigo Girls.”

Erica Rand

Many anticipated that Barbie might have overt feminist and queer themes with Gerwig and actor Margot Robbie, as Barbie, at the helm. The latter co-founded the female-focused production company LuckyChap, and the former’s movies, such as Lady Bird, have a reputation for feminist disruption.

The pre-release marketing hinted at such themes, says Rand. “One big ‘queers-come-hither’ moment in the trailer is when Barbie drives along in her Barbie convertible belting out ‘Closer to Fine’ by the Indigo Girls, a classic in the lesbian-girl-with-guitar genre, and it comes up repeatedly in the movie.”

But a nod is as far as it goes, says Rand. “It would be a very different Barbie movie if any character identified the song’s queer fanbase. But the film’s camp sensibility and some glorious queer moments, like the all-Ken production number, should not be overlooked.”

There are other queer moments, including the casting of Hari Nef, a transgender actor, as Doctor Barbie. And, Rand adds, the movie does take on “damaging and contradictory gender expectations.” Still, most of the queerness in the movie’s trailer could be considered “gay window advertising,” Rand told NBC News, where advertisers nod to queer audiences but in a subtle enough way that naysayers don’t notice.

“Queer is partly what you make it; it also isn’t whatever you make of it,” Rand says. “I have to say that I was disappointed — especially amid all that was feminist about it — in the persistent gender binary,” Rand said. “[In the movie,] dolls are Barbie or Ken, people are men or women. No one’s asking anyone their pronouns.”

Rand also noted that — as in Barbie’s plastic world — the primary Barbie and Ken remain white. “The film can call the main characters ‘Stereotypical Barbie’ and ‘Stereotypical Ken’ but that doesn’t change the predominant importance of white characters.”

At Bates, Jon Cavallero teaches film theory, among other courses, and is the author of Hollywood’s Italian American Filmmakers: Capra, Scorsese, Savoca, Coppola, and Tarantino. Every other year, he and his students produce the Bates Film Festival.

“[Barbenheimer] frames Barbie as the silly movie and Oppenheimer as the serious one. That does a disservice to Barbie, Greta Gerwig, and Margot Robbie.”

Jon Cavallero

He, too, has thought about Barbie through the lens of the audience experience, including how the bright pink Barbie and its fellow opening weekend blockbuster, Oppenheimer, a grim thriller about the birth of the nuclear age, became an internet pop-culture mashup meme: “Barbenheimer,” with fans making plans to see both as a unique cinematic experience.

He recalls how a former student recently told him that friends were urging him to see Barbie and Oppenheimer back to back because, they said, “you’re such a film guy.” Cavallero’s response to his former student flipped the script. “Because you’re the film guy, you have to watch them separately.” In other words, “you have to give them their own space to let them breathe.”

The Barbenheimer mashup, Cavallero argues, creates a troubling binary, in this case “framing Barbie as the silly movie and Oppenheimer as the serious one. That does a disservice to Barbie, Greta Gerwig, and Margot Robbie — an incredibly talented actress who has worked with well-known male directors who don’t make full use of her talent.”

Far too often, Cavallero says, directors “place Robbie in front of the camera and let it merely capture her beauty. Check out her Oscar-nominated performances in Bombshell and I, Tonya or her turn as Nellie LaRoy in last year’s Babylon to get a sense of her range and skill.”

While Barbie’s queer content exists mostly as winks and nods, Rand finds a nod to another identity almost more interesting. That happens with the nonfictional character Ruth Handler, who Mattel now advertises as the inventor of Barbie — though that origin story is not completely true, says Rand — and who appears in the movie, as “a fairy-godmother of sorts, a guide to freedom and human feeling,” she says.

“The meaning of cultural products always depends partly on what consumers bring to them.”

Erica Rand

Handler, who died in 2002 and was Jewish, “is played as an implicitly Jewish grandmotherly type by the actor Rhea Perlman, also Jewish,” Rand says. “Noting that queer and ethnic content — and content producers — have intertwined histories of erasure, I find it interesting that Jewish content dwells even more at the level of suggestion than queer content.”

Rand points out that when pondering, attending, or reflecting on a movie like Barbie, you have to acknowledge the audience, because “the meaning of cultural products,” whether a doll or a Hollywood blockbuster, “always depends partly on what consumers bring to them.”

For example, she notes, “I might consider Barbie as an ad for the cisgender binary, but others might bring different interpretations and experiences to it, including their history of encountering Barbie and Barbie products.” Many people, she notes, remember making Barbie genderqueer as children or might now think of Mattel’s Laverne Cox doll as transgender Barbie. “The many queer and trans fans of the doll and the film teach me not to make pronouncements that quantify queerness.”

Whether Barbie or Oppenheimer, movies are complex cultural products, often disconcerting and contradictory, yet they still “can unite us in a way that few other things can,” says Cavallero. “This idea is at the core of the Bates Film Festival: Movies are among an increasingly rare number of spaces where people from different backgrounds and perspectives can come together and they can use their reaction to a film to discuss more controversial social and political issues.”

Notwithstanding the cinematic excellence that Gerwig and Robbie have delivered in Barbie, Cavallero sounds a warning note about the continued rise of the movie franchise. “One way to judge the strength of a studio is to identify which franchises they control,” he said.

Paramount, for example, “controls Star Trek, Mission Impossible, Transformers, and other Hasbro IP, and Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles. They’ve resurrected Top Gun and they’ve got all the Nickelodeon stuff, like PAW Patrol.”

Movies are just the start of franchising. “It’s merchandising: books, lunch boxes, action figures, video games, and bedsheets. The list goes on. It’s a juggernaut. And certainly Mattel and Warner Media are hoping Barbie will be the start of a long line of movies and other products that bring more profit to their multi-billion dollar companies.”

The worry, however, is a future where filmmakers are forced to recycle something — a character like Top Gun’s Maverick Mitchell — in order to tell a new movie story.

Cavallero compares Barbie with the acclaimed movie A Thousand and One, which won the Sundance Film Festival’s grand jury prize. “It’s a film about a lot of things: a Black family in New York, gentrification, the power of Black women, the foster care system, the bond between mother and child.”

A movie with such topical and challenging themes “is hard to sell. With Barbie, you don’t have to do a lot of selling. People already have an idea of what the movie is about, although some viewers have become angry and dismissive when the film resisted their expectations.”

Of course, Cavallero says, it’s not completely either/or. “It would be silly to say that all sequels and franchise films are terrible. They’re not.” The worry, however, is a future where filmmakers are forced to recycle something — a character like Top Gun’s Maverick Mitchell — in order to tell a new movie story.

If that happens, asks Cavallero, “to what extent are you limiting the possibilities — not just of the medium and the art form but also the artists who are working within it? Where are the original characters?”