Michel Droge, a visiting assistant professor in art and visual culture, spent a summer month off the western shore of Costa Rica as an artist-in-residence alongside a group of international scientists probing the depths of the Dorado Outcrop. The voyage was not just a high-seas adventure, but a journey showcasing the unexpected links between art and science, as Droge recorded the expedition through watercolor, oil paint, and drawings.

The scientists were exploring unseen areas of the ocean floor and studying the outcrop and its hydrothermal vents, home to ecosystems that are potentially vulnerable to deep sea mining.

“I think that it’s important that we make work like this because people don’t get to see the deep sea everyday,” said Droge. “And when we can’t see something, it’s kind of ‘out of sight, out of mind.’ I think if we can expose people as much as possible to this rich, amazing environment, and the extremely important ecosystems that exist there, and if people can visualize it and connect with it, then they’re more apt to care.”

In recent years, Droge’s creative partnership with Beth Orcutt, a senior research scientist at Maine-based Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, inspired multiple paintings that explore the wonder and potential of the deep sea.

After that project culminated with the 2022 exhibit All the Light Below, Droge began to set their sights on a new source of inspiration and connection. “I really thought an immersive experience might be good, but I didn’t think that was on the radar.”

But it soon was, when Orcutt reached out and asked if Droge wanted to join an expedition to the outcrop, located just off the west coast of Costa Rica, as a resident artist, joining Costa Rican artist Carlos Hiller, to document the discoveries with art.

Back in 2013, an expedition to the same outcrop had discovered a group of female octopuses laying their eggs along the outcrop. Yet no developing embryos were found, leading scientists to believe that conditions at the Dorado Outcrop might not support a true octopus nursery.

That mystery was on the minds of researchers for June’s return expedition, dubbed the “Octopus Odyssey,” and organized by the Schmidt Ocean Institute and led by Orcutt and Jorge Cortes of the University of Costa Rica.

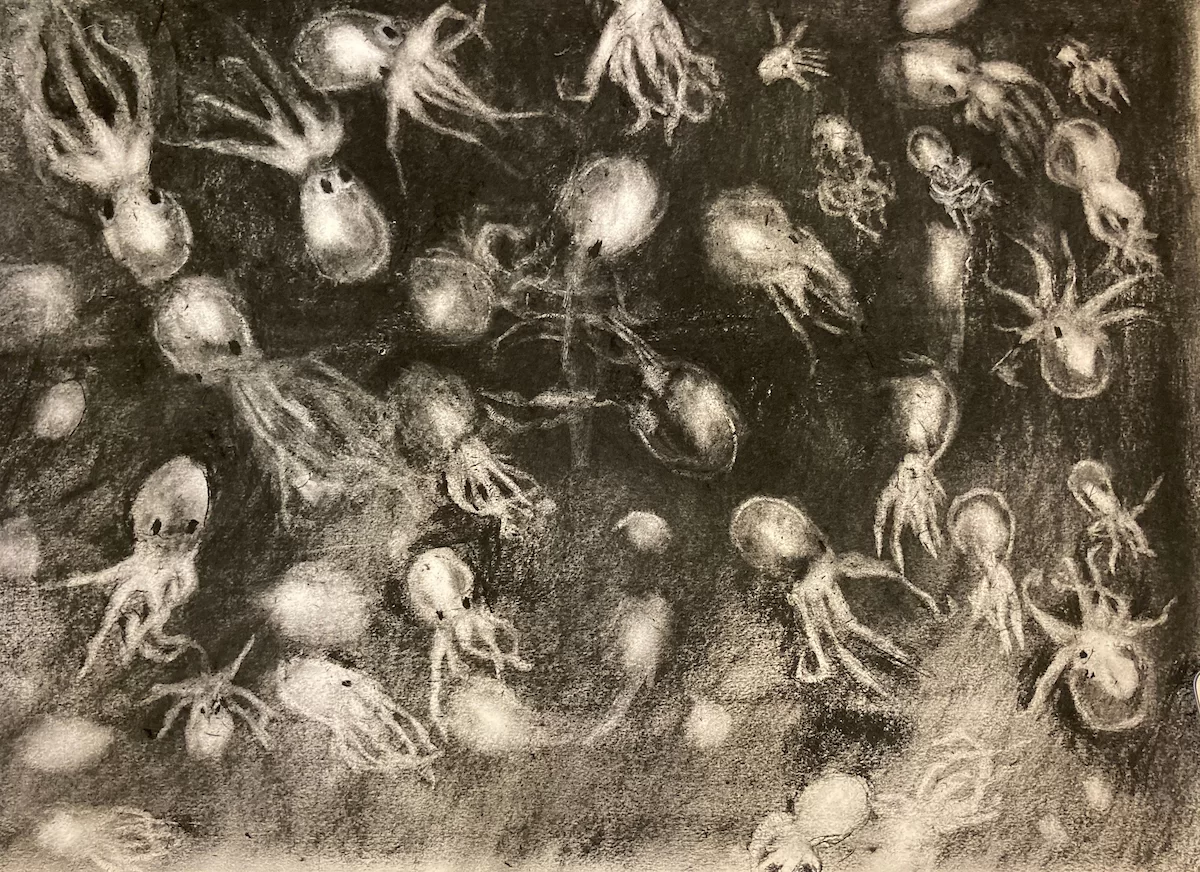

During the expedition, the scientists solved the mystery by finding an active octopus nursery, which disproved the idea that the area is inhospitable for developing octopus young. They found that hot spring-like water flowing from low-temperature hydrothermal vents in the outcrop created the perfect conditions for a nursery, and they witnessed the hatch of a potential new species of Muusoctopus, a genus of small- to medium-sized octopus that lack ink sacs.

Aboard the institute’s research vessel, Falkor (too), Droge soaked up the buzz of scientific discovery and the collaborative work with the scientists. Every day the team would sink SuBastian, their remote-controlled submersible vehicle, to explore and collect samples. Droge and Hiller would help the crew unload the samples at night, getting hands-on experience studying their subjects.

“It was something that everyone was involved in,” Droge said of the work handling the samples of sediment, coral, and live marine organisms. “[We] would get in line and help get the buckets of cold seawater and samples off the submersible.”

Droge and Hiller used samples of the sediment to mix into their paint. In a lot of ways, an art studio and a laboratory aren’t so different, said Droge. To this day, researchers create artwork, whether by hand or by computer, to illustrate their findings.

The relationship between scientist and artist used to be much closer, they explained. “Now it’s more separated. But I feel like that connection makes sense, and I’m curious about how we can bring that sort of 19th-century naturalist into this contemporary world, but still bring art and science together in a way that’s meaningful.”

Droge is well-known for creating art with a queer lens, an awareness that assumptions related to gender, sexuality, and identity shapes our understanding of life — above and below the surface of the ocean. Indeed, the creatures of the deep sea exhibit gender and sexuality in a “much much more expansive way than human beings,” Droge explained.

“So many deep sea creatures are hermaphrodites, and they’ll shift from male-female mating to mating with themselves in order for the species to survive, because they’re very rare.”

The dives were broadcast on TV screens all over the ship — including the mess hall — and livestreamed on the institute’s YouTube channel. Droge spent the weeks watching, talking with the team, and creating art, even inside the labs.

One of the species that fascinated Droge was the tripod fish, which uses its much-elongated tail and pelvic fins to balance on the ocean floor, looking like something “made up, like a dream, or like a Dr. Seuss drawing.”

“There were so many crazy things that I’d never seen,” said Droge.

Many creatures made their way into the paintings, including comb jellies, which undulate through the darkness like what Droge called bioluminescent disco lights, and Venus’ flower basket, a kind of glass sponge that has a symbiotic relationship with glass sponge shrimp.

The shrimp swim into the latticed sponge and take up residence, growing too big to exit and get trapped. Usually a male-female pair, they then spawn, and the babies swim away, to start the cycle in another sponge.

In their month on the ship, Droge completed 11 paintings that are on exhibition at the University of Costa Rica. Now they’re working on a second body of work, using sketchbooks and audio and video footage gathered during the expedition, which will travel with the Schmidt Ocean Institute to museums and galleries around the world.

It’s been “an amazing adventure the past couple of years,” said Droge, and “to get to go on the boat trip was like a dream I didn’t even know how to dream, but so amazing.”