Unlike many students starting college for the first time, Logan Yogi ’27 of Kaneohe, Hawaii, didn’t want to leave her home on O’ahu to come to Bates last month.

That’s because the deadly wildfires that consumed nearby Maui in early August left her shaken, worried about the friends and family in her close-knit Hawaiian community, and feeling she needed to do more.

“My sister and I had survivor’s remorse,” said Yogi.

Including Yogi, there are nine current Bates students from Hawaii and a handful of alumni who live on Maui — including one who was on the front lines of the medical response as a paramedic. In interviews, many worry how the people from Maui who are now homeless will move forward. They worry that the nation’s concern for Hawaii is all but certain to die out, and how the disaster might force a massive dislocation of people who have lived on Maui for generations.

According to the Maui Emergency Management Agency, it will take an estimated $5.5 billion to rebuild from the fire that destroyed much of the town of Lahaina. The fires killed more than 100 people and damaged or destroyed more than 2,200 buildings, 86 percent of which were residential homes, the agency reported. About half of the roughly 30 friends and family Yogi knows on Maui lost their homes.

All of which was on Yogi’s mind as she left home for the 5,100 mile trip to Bates in late August. Though feeling deep remorse, she arrived with a goal: “to bring awareness, even though we’re across the country. I wanted to bring awareness because every little bit helps.”

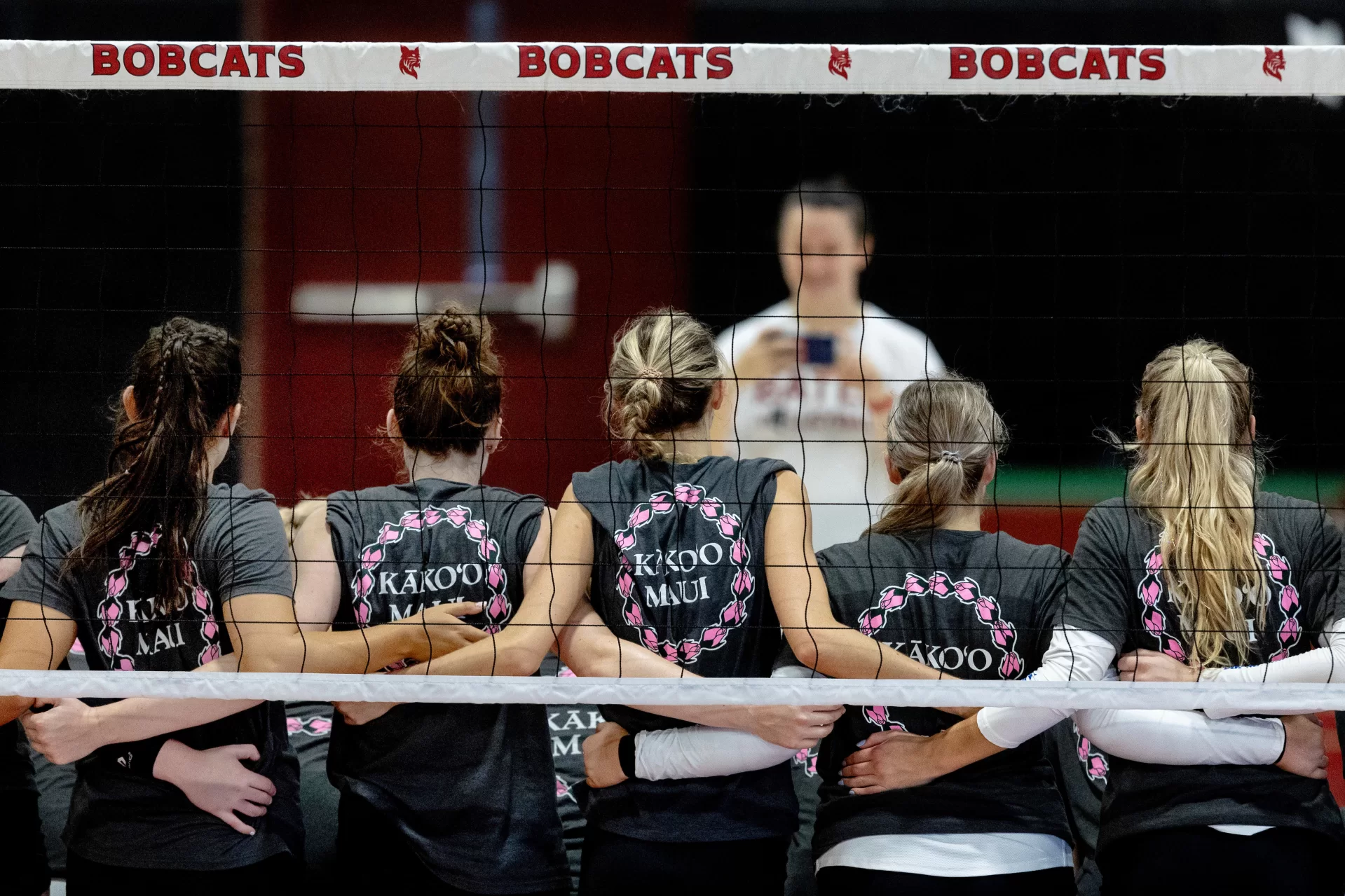

Two weeks ago, Yogi worked with her teammates on the Bates volleyball team, including two others who are from Hawaii, to hold a fundraiser at their home matches on Sept. 7 and 8 to raise funds for the Hawaii Community Foundation, which supports the relief efforts through the Maui Strong Fund.

She recalls how little more than a month ago her social media feeds were filled with horrific images of destruction, razed homes, and the once vibrant seaside city of Lahaina in ruins. There were days she and her sister, Jordan, didn’t want to turn on the television.

“My fear is that Lahaina will never be the same again. People already are scavenging to buy land and make it more of a tourist spot,” Yogi said.

“They will price the Hawaiians out of paradise and people who have had generational homes will never get their land back. The Hawaii community, we are so close with each other. When something happens to one person, you feel each other’s pain.”

A paramedic who helped to start Bates Emergency Medical Services as a student, David Kingdon ’98 is now a professor of emergency medical services with the University of Hawaii system, and also works for Maui County EMS.

Working on a solo paramedic Special Response Unit in Ma’alaea, Maui, Kingdon was on the front line helping to triage and transport burn victims during the fires. On Aug. 8, he served as medical command at the mass-casualty incident, working almost non-stop the first four days, including more than 24 hours straight on the scene during his first shift.

In just the initial stage of response, his team treated around 60 patients, and transported 32 to Maui Memorial Hospital, nearly half of whom were flown to a burn center on O’ahu.

“Obviously as a responding paramedic, I was deeply affected by the lives lost. In fact, one of our own off-duty EMTs was killed by the fire. It was such a massive disaster, I don’t think any family on Maui doesn’t know someone who died or lost their home,” Kingdon said.

The night of the intense fires there were at least four different areas on the island with major fires, which grew and moved with unexpected force. At one point, when a fire suddenly changed directions and bore down on Kingdon’s command post, he had to drive his response vehicle through the flames to escape.

An off-duty paramedic from Kingdon’s unit got his family to safety, reported to the triage center, then used his personal pickup truck as a medic utility vehicle to respond to area as his home burned to the ground. Kingdon said his team worked valiantly. They also tried to help with evacuations to the extent they could. But weeks later, he said he was still reeling from the devastation and death toll.

“Of course, that’s one of the hardest things for us to live with, wishing we got more people out, wondering if we could have,” Kingdon wrote in an email to dozens of concerned family members and friends, many of whom were Bates classmates.

Kingdon is married to Roxanne Gillespie ’99. They live in Wailuku, where they raised their two children, now teenagers. They were fortunate in that the area where they live was one of the few parts of the island that escaped the worst of the fires.

But Kingdon said it’s shocking how many homes and buildings on the island were lost. Just two days before the fires, their family went sailing off the coast of Lahaina. Now Lahaina Harbor and the entire historic city, once the capital of the native Hawaiian Kingdom, is decimated. Kingdon called it “apocalyptic.”

Gillespie remains concerned for their neighbors and friends who live in Lahaina, including one family who lost their home and came to live with them for a month.

In the early 2000s, Gillespie, a speech-language pathologist, served many families and children in their homes in Lahaina. She immediately worried about mothers trying to evacuate with their young children during the fires.

“As soon as I realized where the Lahaina fire was located, I didn’t think of specific families so much as all the women with infants and toddlers without transportation who lived in those neighborhoods,” Gillespie said in an email.

For other Bates students from Hawaii, the uncertain future so many on Maui now face is hard to fathom.

Max King ‘26 of Kalaheo, which is located on the island of Kaua’i, worries how the rebuilding that takes place on Maui might squeeze out the locals who can no longer afford the new construction.

King has met many people at Bates who have vacationed in Hawaii and he said they often are eager to share with him their memories of the fantastical wild landscape there. He hopes such beautiful memories will inspire generosity and people might “turn those memories into compassion.”

“Billions of dollars will be needed to rebuild. It’s important that people who have been there can help out, so they help preserve the island,” King said.

King, who was born in Hawaii, considers the people of Maui his neighbors with whom he shares the same culture and identity, even though he doesn’t have any friends or family on the island.

“It’s definitely one big community,” said King. “I had a little bit of a culture shock coming to Bates. I know everyone does, but the people of Hawaii are just special. They are the friendliest people I’ve ever met.”

Ami Evans ’26 of Honolulu, who is also a member of the Bobcats’ volleyball team, worked at a restaurant this summer on the island of O’ahu, where donations poured in as locals gave clothes, pillows, stuffed animals for children, even toilet paper. So much is still needed, she said.

Now that the tourist area around Lahaina has to be rebuilt, Evans also fears native Hawaiians will be priced out and displaced, and have to leave their homeland forever.

“On a local Instagram there is a lot of talk about that,” Evans said. “People are also upset about the tourists coming. That’s an ongoing issue in Hawaii in general — people from the mainland want to move there and then local people can’t afford to live in the houses. It’s kind of sad. It takes away from the natural Hawaii.”

Evans is fiercely proud to have been born in Hawaii and to call it home. The culture, she said, is authentic and rooted in friendship.

“Everyone is so respectful of each other. Strangers are always nice to each other. Everyone is so friendly. It’s different from the mainland,” Evans said. “They call old people ‘aunty’ and ‘uncle,’ even if they don’t know them at all. It’s a unique culture, a special culture.”