Among the bygone realities of life on the Bates campus many years ago were these two:

- The campus was woken weekday mornings by the ringing of the Hathorn Hall bell — at 6:30 a.m.

- Said bell was rung not only at 6:30 a.m., but up to 19 more times every day, the final time at 5:20 p.m. as a call to dinner — by students who lived in Hathorn Hall.

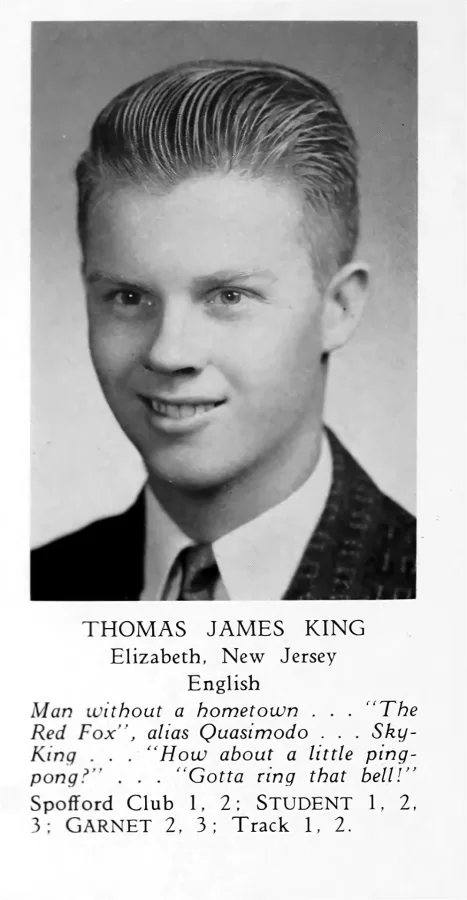

One of those student ringers was Tom King ’58. In fact, he’s believed to be the last in a long line of student bell ringers before automation took over. And we know about the final bell ringer thanks to a long Bates friendship between King and Chris Bond ’81, both residents of Carmichael, Calif.

The two met years ago at a cocktail party and found, in addition to a shared Bates degree, they also shared a love of literature. (King had a long career as a professor at American River College in Sacramento and has published novels, essays, and poems.)

One day, their conversation turned to King’s unusual campus job as a bell ringer, a job that necessitated living in Hathorn in Spartan conditions — showering meant heading to Parker next door — and many trips from wherever he was on campus back to the second floor of Hathorn to pull the rope to ring the bell for classes, meetings, meals, and chapel (when it was required); after big sports victories; and during Commencement.

The practice of a student bell ringer dates to the 1800s, an era when the Hathorn bell might be the only way for professors and students to know what time it was.

As such, the ringer’s punctuality was sometimes the target of sarcasm in The Bates Student. “The college bell-ringer is to be congratulated on his punctuality,” the Student noted in 1879. “It is a comfort to feel that all hours of the day are to be of the same length.”

A 1953 issue of the Student reported that one of the bell ringers, John MacDuffie ’53, “kept a record and came out with the amazing news that they rang that bell almost 100 times a week. It…sometimes rings as late as 11:30 p.m. after a triumphant basketball game.”

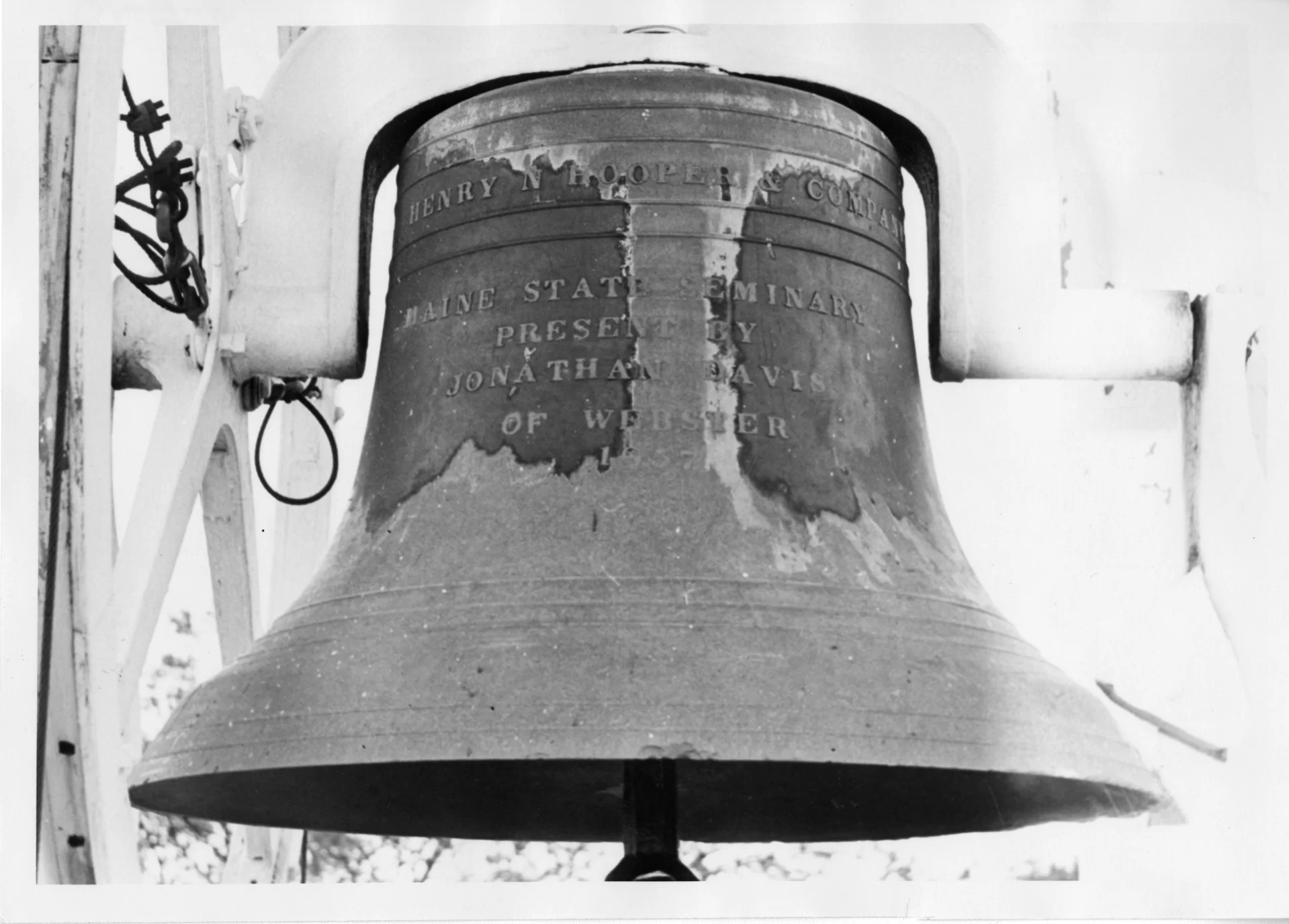

As to the bell today, the college recently completed improvements to the attic of Hathorn, including a new HVAC machine, walkways, lighting, and retractable stairs for access. The project sets the stage for replacement of the old and problematic , with a winch and cable setup used to swing the historic half-ton bell, given to the college in 1857. (And contrary to lore, there is no recorded version of the bell sounds)

Here is an edited version of Bond’s conversation with King about his job as a Hathorn bell ringer (a job that did include some perks) and other stories about his experience, offering a window into Bates campus life in the 1950s.

Chris Bond ’81: How did you happen to attend Bates?

Tom King ’58: My mother was the sole parent and she had pulled off a sort of miracle by becoming a department store buyer without having ever gone to college. Every other buyer in the profession was college taught.

Out of sheer pluck, she had raised herself up by her spiked heels and become a feisty Southern-belle buyer. And because she had done it the hard way, she wanted to make sure that I got a college education, so she sacrificed tremendously to put me through college.

As a senior in high school in Asbury Park, N.J., I applied to several colleges, and Bates was one of the ones that accepted me. I felt it was a romantic idea to attend a college in New England, alien to me except through reading Robert Frost.

Bond: How did things go at the start?

King: Freshman year I roomed in Roger Williams with three other fellows, and because I was always an introvert it was good for me to unwind a little bit, with more social contact than usual.

I wouldn’t say I was happy, but I was getting someplace in my life.

My poverty meant I had to constantly work in the kitchen [in Chase Hall] in order to stay in college, resulting in continual fatigue and theft of hours that might have been devoted to study, keeping my grades mediocre.

Bond: What was the crisis you faced at the end of sophomore year?

King: My mother had been able to fund my attendance with her out-of-pocket support along with what loans we could set up. However, in my sophomore year her store in New Jersey closed and she had to look for another job. Suddenly it looked like I was not going to be able to finish college.

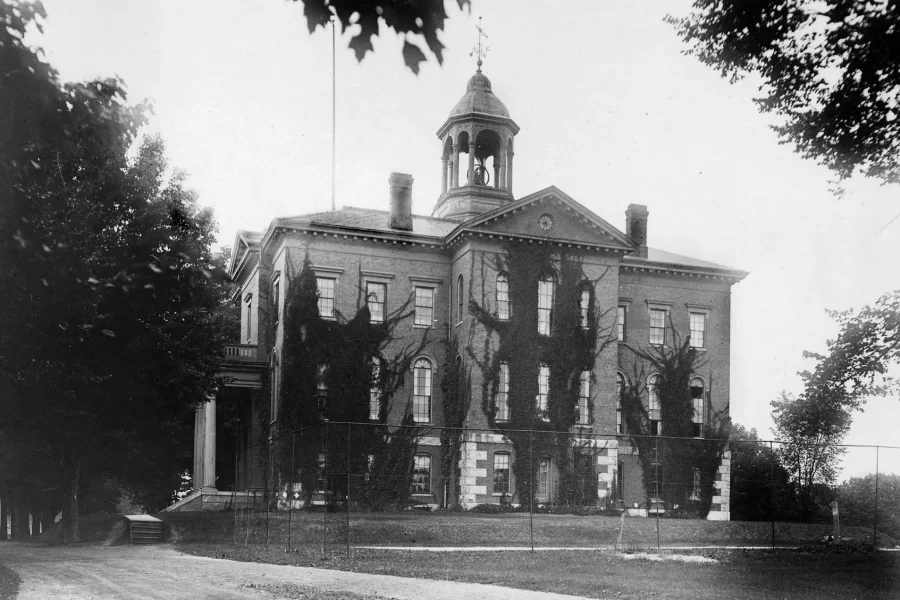

And then another player comes into the plot: Dean of Men Walter Boyce. He was sort of Lincolnesque — over 6 feet tall, lean and austere. Everyone looked up to him. Dean Boyce took mercy upon me when he understood the situation. He went to work and, along with a loan, got me a highly unusual appointment: a job lodged in the bell tower of Hathorn Hall, which came with a stipend enabling me to continue with college by ringing its bells.

Bond: What was entailed in your role as Bates bellringer?

King: I was lodged in a room on the top floor of Hathorn Hall. It looked like just another classroom from the corridor, but that was where I and one other bellringer were living. The lodging consisted of upper and lower bunks (I had the top bunk), two desks, and that was it.

Out of the ceiling hung this boa-constrictor-like rope as big around as Arnold Schwarzenegger’s thigh, which came down alongside the bunk bed.

For two years I was bellringer, with two different roommates to share the duties. (We were never good friends, just tolerable roommates.) My first task at 6 o’clock each morning, straining to get the rhythm going, was ringing that thousand-pound bell to wake the campus. The two of us were required to ring for all the classes through the course of the day. Yes, it was a bit of a frenzy sometimes. And we had automatic permission to come in late for our classes.

Bond: All tolled (so to speak), how many times did you ring the bell each day?

King: I think maybe I would swing on that big rope about a half dozen times a day. I might mention that I rang the bell and then five minutes later I had to ring it again, telling the students they were late.

Bond: What else do you remember about your lodgings in Hathorn?

TK: One colorful aspect of the situation is that there was a small door, lowdown, and you could crawl through this door and it would take you to this maze, a dark labyrinth, that included ladders leading up to the roof.

“Rachmaninoff sent out into the sleeping dark! It was a great delight occasioning my music-starved youth.”

Tom King ’58

And some of the time, let’s say on a weekend, it was very pleasant to invite a fellow classmate to climb that final ladder all the way up to the roof and sit up there, maybe have a couple of beers. The view was stupendous. Looking down on the campus, I felt sort of like the king of what I surveyed, since I was the bellringer, you know.

Bond: I can envision you up there, with a view worthy of Quasimodo atop Notre Dame.

King: Yeah. Observe, though, that, distant from my former dorm, and because I didn’t make a strong connection with my belfry roommates, lodging in Hathorn contributed to my sense of isolation. The hermit-like life of an introvert ran against what influences might have offered a strong social education.

Bond: It must have been pretty quiet.

King: It was interesting, because it was a total transformation. You know, there’d be all kinds of noise, students and teachers getting to their classes outside the door during the day, and then afterwards, it would just be as solitary as a grave.

I’m reminded, though, of another perk. On the first floor where Cultural Heritage met, one of the classrooms contained an LP player. And sometimes in the dark of night I would steal down and find records there and play classical romantic pieces. Rachmaninoff sent out into the sleeping dark! It was a great delight occasioning my music-starved youth.

Bond: So, you were responsible for waking up the campus. What time did you wake up?

King: Well before 6, but the trouble was that I was always behind in my studies because I worked in the kitchen. So I’d often be studying through the night to make up for what I didn’t get prepared for class. I had no alarm clock, and finally dropping back off to sleep in early morning would sometimes cause me to miss a bell. I’d anxiously await reprimand, but none came.

Bond: What were your duties in the kitchen?

King: I was in the dish room. The students brought in their plates, which had to be scraped of the residue from their meals into the garbage bin. Then you had to incipiently clean them before loading them into the automatic washer.

After automation had sent the dishes through a wash, the task was removing the dishes from the dishwasher, drying them, stacking them on carts, and bringing them out for further use.

Bond: What else stands out in your mind from those early Bates years?

King: Something never to be forgotten, called Mayoralty. Every spring the campus was transformed for three days into something quite wonderful. And all the rest of the time a great many of the students prepared for the subsequent year’s event — it was that thrilling to everybody.

Mayoralty consisted of the male student population being divided into two halves and those two clans vying against each other for the votes of the campus’s coeds to get their candidate elected mayor.

Because it was taken in such deadly earnest, everything was magically transformed during those three days. For instance, when I arrived as a freshman, we decided that year that we were going to do a Scottish theme, so the males on our side, every one of us, were decked out in kilts. Imagine a campus swarming with identical sky-blue kilts in full regalia, including boots and dapper caps.

But that just doesn’t begin to give the full picture. What was hard for me to ever understand is how, with such a limited total enrollment — I think the full enrollment was only around 800 students — there could be so much talent packed into that campus. They would produce entire Broadway shows. We put on Brigadoon, with all the dancing and singing.

For our candidate we had chosen Kirk Watson ’56: tall, lean, dark, everything you want in a swashbuckling hero, and this God-sent senior pre-med became “Highland C’ael Kirk.” We were all assembled — the excited components of our side — at the foot of Mount David at twilight.

“And boyo, it was dreamy. It put chills up my spine, because it was just so splendid.”

Tom King ’59

Suddenly we saw, circling the great mount’s higher reaches, heart-lifting Highland Kail Kirk, trailed by his retinue carrying torches and quietly singing, “Once in the highlands, the highlands of Scotland….”

And boyo, it was dreamy. It put chills up my spine, because it was just so splendid, with everything professionally under control, producing that effective Brigadoon theme.

Nor was the thrill lost with subsequent Mayoralties. After Brigadoon, our side tackled Oklahoma! and I had my small contribution behind the scenes helping Jim Kirsch ’58, Bates’ first-string quarterback with scarce experience in public speaking, organize his thoughts well enough to speechify as a credible candidate.

Somehow, we seemed to have the corner on stage talent, and our side kept winning. But the spirit of Mayoralty was far more than a contest.

Bond: Can you talk about the culmination of your years at Bates?

King: In my junior year the chair of the English department sent out an invitation to the student body to write the annual Ivy Day ode. Writing had always been my secret passion, and I entered my ode, and I was awarded the win.

Subsequently I was required to read my ode in the chapel before the full student body. The ensuing stage fright seemed life-threatening. But I got through it.

What is this tyrant, strange dimension, Time

Which scatters old friends forth, like wind the chaff

Unheeding soft-formed sentiments which, born

About these green-lined pathways, subtly thrived?

The answer comes: a stern-voiced mystery-sire

Who, knowing suffering’s methods, thrusts his brood

Forth, like an old, wise parent, from the shade

Of these friendly walls — for our struggle in the sun.

There were two important consequences from writing and publicly reading my Ivy Day ode. The first was confidence I gained from recognition of my talent. The other was a girl, Heather Taurel ’60. What gift I possessed being evident in the ode she heard read brought me to her notice. Eventually, hundreds of miles away from Bates, we married.

It’s true our time together came to a divorce after 10 years. But not before a son and a daughter whose extraordinary humanity topped with charm makes us so proud we never get over the urge to shout our gratitude from the rooftops.