The way to someone’s heart is through their stomach, they say. More important, it’s the route to our overall well-being.

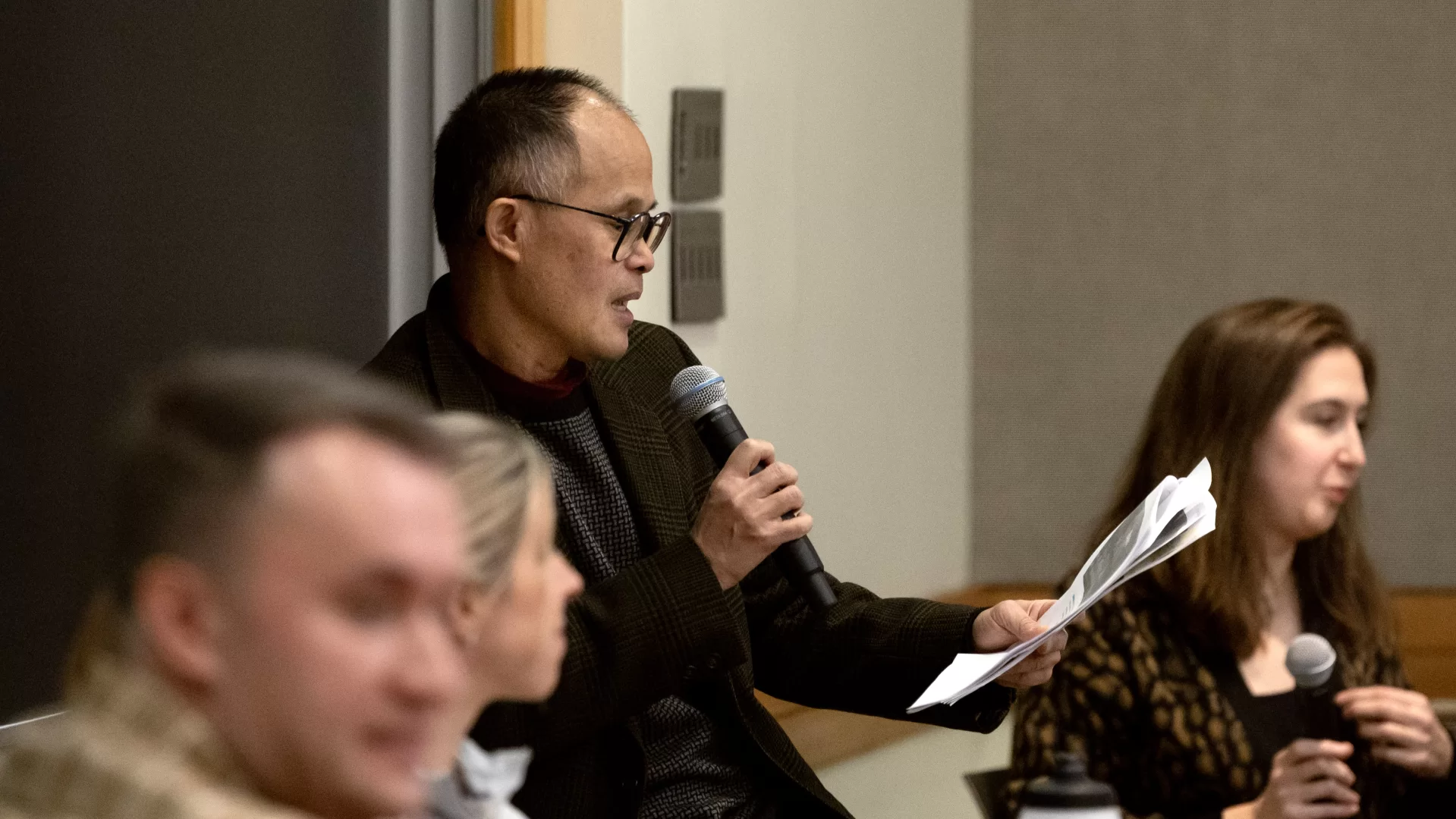

Recently, professionals from the Bates Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS) program gathered to discuss diet and mental health, offering facts and tips, giving cautions about social media, and explaining why you don’t “yuck on someone else’s yums.”

The topic of food and well-being is a vast one, admitted Dr. Susanna Preziosi, a CAPS psychologist who moderated the discussion on Martin Luther King Jr. Day that filled a Pettengill Hall classroom. “We could devote a month-long conference to it.”

And in the coming years, “medicine is going to understand more is the connection between gut and the brain,” said Dr. Heidi Walls.

For example, the majority of the body’s serotonin, which regulates mood, appetite, sleep, and cognition “is actually produced in the gut,” Walls said. “So there is a kind of biological basis for mood connections and our brain. Some people talk about the gut actually is a second brain of the body.”

These days, college students ponder their food choices from a few savvy perspectives. They look for food to fuel their sporting life. They look for food that is organic and/or locally grown. They look for vegan or vegetarian options.

But college students are at the most vulnerable time of their life for eating disorders and mental illness to develop, so it is to their benefit to understand how diet and eating affects mental well-being.

“Good nutrition and well-balanced diets are related to mental health in a variety of ways,” said Dr. Wendy Kjeldgaard, a CAPS psychologist who specializes in treating eating disorders.

Food and diet, Kjeldgaard said, affect “your cognitive functioning, your ability to regulate stress, your capacity to experience really strong, powerful, negative emotions.”

When it comes to the gut-to-brain roadway, “some people talk about the gut as a second brain, which is really fascinating,” said Walls, who serves as head team physician for Bates Athletics. “The majority of the body’s serotonin is actually produced in the gut. So there’s a biological basis that makes sense for some of these food connections and our brain.”

Which means, said Brandon Ouellette, a CAPS counselor, “when you have a gut feeling, you really are having a gut feeling.”

But there are roadblocks between the stomach and brain, the experts explained. From the perspective of working with athletes focused on diet to create the best body possible for their sport, Walls says that she is “always fighting the idea that smaller is faster when it comes to sports.”

Many people assume there’s a certain body that is healthier or more athletic, “and we think of those as being related to weight,” Walls said. “But it’s important to realize that we completely cannot tell someone’s health from the outside of their body.”

In an ideal world, added Kjeldgaard, “food and weight and emotion and shape would not have to be tied together.” She referenced the Health at Every Size movement, noting that “you can be perfectly healthy, medically stable, at many different weights. And just because you’re smaller, that doesn’t mean you’re healthier.”

A student’s homesickness might be exacerbated by missing the comfort of home cooking, whether the cooking is from their home in China or the coast of Maine. “Food is important to who we are, our identity,” said Walls, who recounted her return from study abroad during college, and how her mother asked, “What can I make you for dinner now that you’re home?” To which Walls, who is from Maine, replied: “All I want is a red hot dog. That was the thing that I wanted and missed.”

Kjeldgaar told the students that certain behaviors around eating can affect other parts of your personality.” She pointed to the landmark Minnesota Starvation Experience in 1944–45, the first to make a connection between behavior and a restricted food intake.

When study subjects restricted their food intake, “they started to exhibit the kind of behaviors that people with disordered eating do,” she explained. “They became very rigid in terms of behavior. Their cognitive flexibility decreased, and they became obsessive and compulsive in their exercise behaviors. Their world just started getting smaller and smaller.”

Also important is our state of mind—calm or jazzed up—when we eat, said Walls. Humans have two nervous systems that control our involuntary bodily functions. There’s the sympathetic system, often called the fight-or-flight response. And there’s the parasympathetic nervous system, the rest-and-digest response that occurs when you are sleeping, napping, meditating, or digesting your food.

“Eating in an environment or situation where you’re having an increased sympathetic ‘tone’ is going to make it harder to get the parasympathetic drive you want to digest food,” Walls said.

If possible, students should find a way to chill out when they eat — the parasympathetic state, keeping in mind, the experts acknowledged, that setting aside time to dine can be hard and social anxiety around eating in a large dining hall like Commons is real.

A decade ago, Snickers landed on a tagline, “You’re not yourself when you’re hungry,” that became famous partly because it’s so true. “Everyone’s had an experience of being hangry,” said Ouellette, the CAPS counselor, “when you’re so hungry it’s all consuming and it puts you in such a bad mood. The way that we satisfy those physical needs is going to affect our mental health, as well.”

To avoid the hangries, Ouellette encouraged the students to be self-aware about how hunger affects their mood.

“I’ve worked with children, and nine times out of 10, when a child had a meltdown, my first response was, ‘Do you need a snack? Are we hungry? Are we thirsty? Do we need to use the bathroom?’ And nine times out of 10, it was coming from a physical sensation that was really difficult.” We experience that as adults, too, Ouellette said.

Students are busy and under stress and pressure — classes, extracurriculars, and trying to make time for relationships — “some really important body maintenance things can start to fall by the wayside,” he said. “I’m always talking to clients about making sure you’re eating throughout the day. If you have a really busy afternoon, grab a banana or an apple or a little snack from Commons to bring with you.”

During the Q&A, a Bates student asked how they could help friends who seem to struggle with food issues.

Ouellette encouraged being candid and acknowledging the discomfort of discussing sensitive topics, like food behavior. The panelists also offered online resources and toolkits, including the National Eating Disorder Association. They welcomed students to come into CAPS for advice.

Walls said that “it’s never wrong to tell someone that you care about them and that you’re worried about them. Even if it comes out kind of messy, it’s probably better than not saying anything at all.”

The experts also advised not commenting on a friend’s diet, food, or meal, to “not yuck on other people’s yums,” said Kjeldgaard. If a friend is in need, Walls said, “the first thing is to stop body talk. I know I’ve been guilty of it before: ‘I shouldn’t have eaten that, I feel guilty, I need to lose 10 pounds.’”

A proactive way for a student to take control of their relationship between their mental well-being and food is to be savvy about their social media use and the information pushed out on social media.

Certain uses of photo-centric social media apps, like Instagram or Tik-Tok, “can put you at higher risk for developing body satisfaction or disordered eating.”

“This is my dream come true,” said Kjeldgaard about the chance to offer advice to students about how they gather facts about diet, including problematic fad diets like Keto.

Kjeldgaard noted a study that found that nearly 50 percent of people said they learned about food and eating through social media, while around 22 percent learned from nutrition professionals. “You need to be wary of who’s giving you information, how much of it is driven by their desire to get more likes and clicks,” she said.

She noted that certain uses of photo-centric social media apps, like Instagram or Tik-Tok, “can put you at higher risk for developing body satisfaction or disordered eating.” For example, there’s the problem of permanence: “You can revisit old photos or old feedback, including negative comments, and it’s very easy to compare current photos of yourself with old photos of yourself or of other people.”

There’s also the absence of interpersonal cues when communicating using social media, which Kjeldgaard said can heighten social anxiety. The wide accessibility of social media content can “exacerbate the psychological concept of an imaginary audience, common in adolescents or later adolescents, where you think people are paying attention to you all the time.”

Like the many other presentations on MLK Day, the CAPS session reflected this year’s chosen theme of “Food Justice.”

“Food and mental well-being does not exist in isolation. It exists in community,” said Wayne Assing, director of Bates CAPS. “In the spirit of Dr. Martin Luther King, I’d like to consider that food is life, injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere, and thus food injustice anywhere is a threat to food justice everywhere.”

The experts homed in on how marginalized communities bear the brunt of food-related injustices. For example, sometimes when children who have experienced neglect and food insecurity at home are brought to a foster home where food is readily available, they show binge-eating behaviors.

BIPOC communities have higher rates than white communities of eating disorders, said Kjeldgaard. And another population that really struggles with disordered eating and eating disorders is the LGBTQ+ population, where there are dramatically higher rates versus cisgender communities or heterosexual communities, Kjeldgaard said.

“Members of the queer community are more likely to experience food insecurity,” added Ouellette. “So food insecurity and eating disorders are linked in that way.”

To put all the pieces of advice in perspective, Assing referred to chef and author Bryant Terry’s keynote speech where he talked about gaining confidence as a cook, “where you’re using your intuition.”

Assing hopes Bates students can achieve something similar in their relationship to food and eating: confidence, independence, and intuition.

He encouraged the students to be kind to themselves. “This is a journey and the journey is a journey of balance. None of us is going to be perfect. None of us is ever going to get it right.”

As Kjeldgaard said, “Not every meal’s going to be perfect. Not every snack’s going to be perfect.”

Instead of judgment and perfection, said Assing, students should try to ask themselves “what does an evolving practice of self-care for you look like in terms of how you navigate your relationship with food with compassion for yourself and with others to decrease this sense of judgment? Our judgment can really affect one’s gut as people have said, which really can create a lot of stress.

“The message is trust yourself. Listen to yourself, be in relationship to your needs in a given moment. Health is always a balancing act.”