Wearing an apron and standing at a lectern beside a table full of mixing bowls and vegetables, Bryant Terry showed the crowd gathered in Gomes Chapel on Martin Luther King Jr. Day just how communal, joyful, and personal food is to him by opening his keynote address with a soulful rendition of the song his grandmother sang while cooking in her kitchen in Memphis, Tenn.

“Glory, glory. Hallelujah. When I lay my burden down, burden down. No more Monday, no more Tuesday, when I lay my burden down,” Terry sang.

An artist, author, activist, and award-winning chef, Terry delivered the Bates MLK Day keynote address on Monday, tying together the problem of food injustice today with the history of Martin Luther King Jr.’s fight against systemic racism during the Civil Rights Movement more than 60 years ago. Along the way, Terry spiced his talk with personal stories and, as a dessert of sorts, ended his presentation with a live cooking demonstration of one of his vegan recipes.

President Garry W. Jenkins first greeted the more than 200 gathered at the observance, explaining that while this year’s Bates MLK Day theme of food justice is a modern-day concern, it is one of many injustices King fought to correct before his life was cut short.

“Dr. King himself was explicitly focused on the issue of food justice,” Jenkins said. “Speaking in Montgomery, Ala., in 1965 he said, ‘Let us march on poverty until no American parent has to skip a meal so that their child may eat.’”

Offering further evidence how King raised awareness about the stark inequalities in the American food system, Jenkins quoted from King’s 1960 speech at Spelman College where King said: “I do believe that in America we must use our vast resources of wealth to bridge the gulf between abject, deadening poverty, and superfluous inordinate wealth.”

Phoebe Stern ’24 of Nashville, Tenn., one of the student representatives on the Bates MLK Day planning committee, briefly spoke about the prevalent inequalities in food systems today. And Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Tyler Harper, the committee’s co-chair, thanked the committee for its work and reinforced the connection between King and food justice.

Describing King’s speech from when he accepted the 1964 Nobel Peace Prize, Harper noted the continuing relevance of King’s message, that “even as our politics feel fraught and perhaps broken, we must not lose sight of the most basic political question of who has food and who does not.”

Then after the MLK Day Keynote speaker greeted the crowd with his grandma’s song, Terry shared with energy, humor, and personal anecdotes how his life’s work came to focus on the fight for healthier, more equitable, and more sustainable food systems.

The James Beard Award–winning chef added with some mirth that in his early days as a food justice activist he was “the most self-righteous, dogmatic, judgmental, vegan that you’ve ever encountered.

“I don’t know if you guys have ever dealt with someone who has a vegan diet, and they are the most self-righteous, finger wagging nanny. That was me, and I apologized to my parents almost every week for putting them through hell for several years because of my zeal.”

On a more serious note, Terry explained how, just as King did, he came to champion the idea that healthy food should be a fundamental human right. The fact that marginalized communities in the United States have less access to healthy, more sustainable food systems, he said, has resulted in food apartheid in our country.

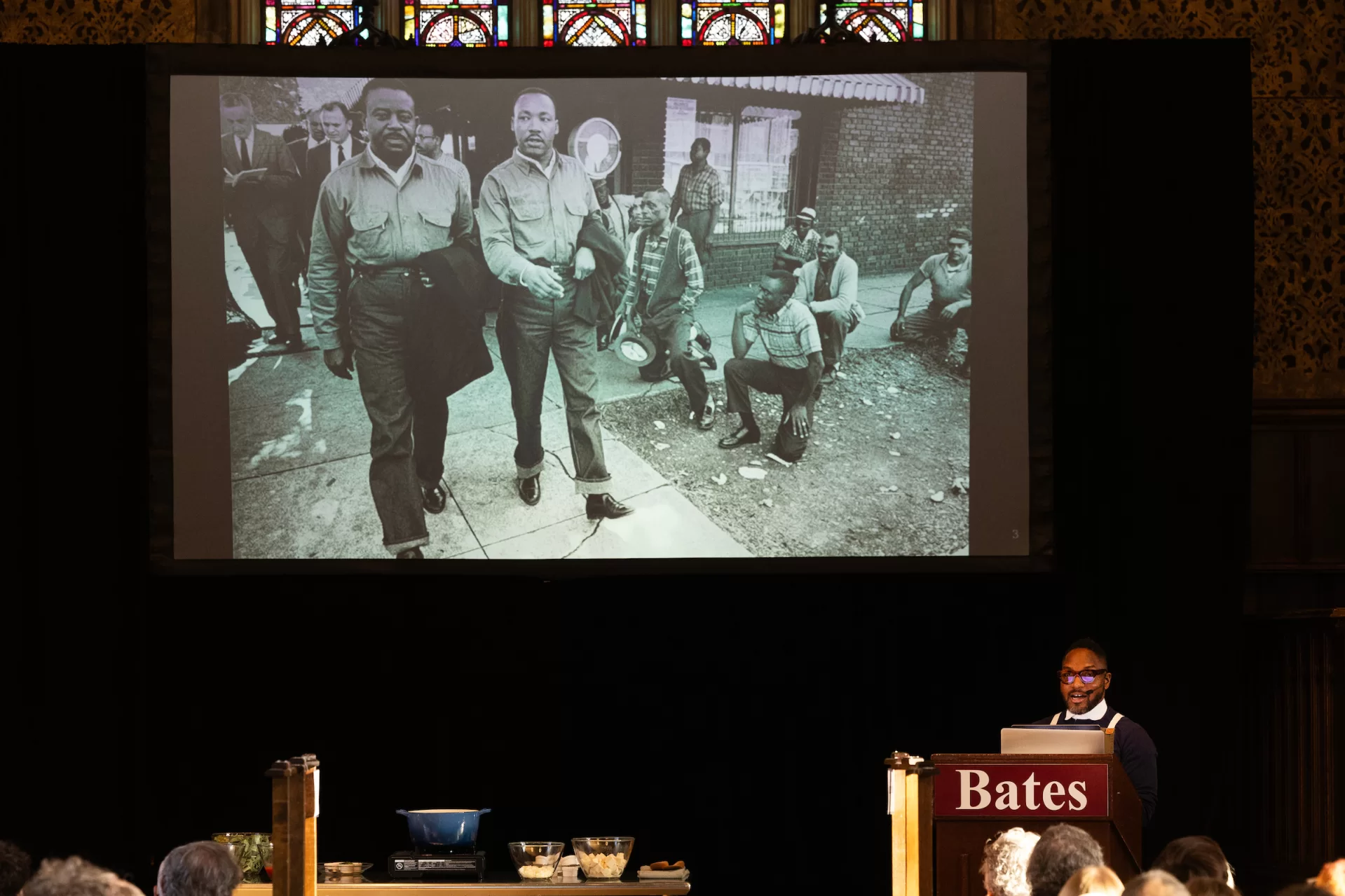

Bryant Terry displays a famous photograph of Martin Luther King Jr. and Ralph Abernathy wearing denim work pants and work shirts when they were arrested in Birmingham, Ala., in April 1963. Terry explained how King eshewed tailored suits when he protesting in the South to better connect with everyday people. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Terry explained that he specifically chose the term “food apartheid” rather than the more familiar term “food desert.”

“The word desert almost makes these “economic, physical, geographic barriers that many communities face seem natural. But ‘food apartheid’ refers to the systemic and structural inequalities in the food system resulting in some communities having limited access to healthy, affordable, and culturally appropriate food while others have more abundant access,” he said.

His love of cooking came from his grandparents in Memphis, Tenn., who Terry said used their example of scratch baking and farming to teach him the ideals of “self-determination, practice of generosity, community care and the mutual aid to meet the immediate needs of neighbors and the wider community.” These early life lessons instilled in him a desire for healthier food systems.

View the full Martin Luther King Jr. Day keynote gathering in Gomes Chapel on Jan. 15, 2024:

“My maternal grandmother kept a cupboard in her kitchen that was about 7 feet tall and a foot deep,” he said. “Each shelf crowded with glass jars full of preserves, pickle, pears, peaches, carrots and green beans, figs, blackberry jam, sauerkraut, and her not to be forgotten: chow, chow — cabbage, onions, peppers, chopped finely cooked for about five hours and served as a relish along with leafy greens such as collards, mustards, turnips, kale, dandelions. Listen, my grandmother could work magic in the kitchen.”

His activism took root in culinary school in New York City, at the Natural Gourmet Institute, where he worked to empower young people in neighborhoods affected by food apartheid by teaching them culinary skills and training them in advocacy work. “Our aim was to empower these youth to resist the influence of these corporations and make healthier choices,” Terry said.

Around 2001, Terry said he started advocating more strongly for food justice within marginalized communities after he first attended gatherings aimed at addressing the problem and looked around at those attending.

“These gatherings were predominantly attended by privileged white people, and those who suffered the most from our flawed food system were often absent from the discussions.” He also noticed educational and class biases within the gatherings, and felt those impacted the most by injustices in food systems should have been leading the discussions.

“The conversations often initiated with discussions of public policy and high level intellectual concepts, yet they lack the essential elements of art, culture and a focus on community,” Terry said.

His journey in activism at that time spawned his personal mantra — that he repeats to this day: “Start with the visceral to ignite the cerebral and end with the political.”

While he found inspiration everywhere — in art, music, and literature, including some of the hip hop music he played for those gathered in Gomes — Terry said that two creative works, published 85 years apart, inspired his path forward. One was Upton Sinclair’s expose of the Chicago meat-packing industry, The Jungle. The other was “Beef” by Boogie Down Productions and KRS-One in 1990.

“Surprisingly, it wasn’t a scholarly monograph or a lofty intellectual lecture that profoundly reshaped my habits, attitudes, and political views concerning food. It was a song and a novel,” Terry said.

While a graduate student at New York University in the early 2000s, Terry researched the “methods of resistance employed by the Black working class in the 20th century to combat capitalism and white supremacy,” such as protests and slowdowns in work places that were used as forms of resistance.

Yet, Terry said, he came to advocate for food justice by embracing a simpler approach, such as foraging, cooking, and breaking bread together.

“While the food justice movement engages in organized forms of resistance, I believe it’s equally vital to recognize and celebrate seemingly apolitical acts such as growing food, preparing meals from scratch, and fostering community around our dining tables as profoundly political, dare I say, radical acts of resistance,” Terry said. “I celebrate these everyday acts of resistance and view them as accessible entry points into the food justice movement for everyday people.”

Terry closed his keynote address demonstrating his most favorite everyday act of resistance to food apartheid: A 25-minute cooking demonstration in which he encouraged novices, assuaged cooking fears, and served up humorous stories about spices, tofu, and the pleasure of a communal feast.

When he finished preparing the curry dish from his Afro-Vegan cookbook, Terry thanked the Bates crowd for joining him on his “intellectual and creative journey,” Then he asked those gathered to consider finding their own accessible entry points to the fight for food justice.

“I think whatever talents and skills we could bring to bring us to a tipping point, we should bring those,” Terry said. “You need chefs, you need designers, you need scholars, you need journalists. We need all hands on deck to really work toward what I would argue is one of the most important movements of the 21st century.”

His closing remarks were met with a rousing standing ovation from the Gomes audience.

Associate Dean for International Student Programs James Reese closed the keynote asking the crowd to thank Terry again and encouraging them to go forth and enjoy the day full of workshops, and, importantly, bear in mind that King was mentored by one of Bates’ own: the Rev. Benjamin Elijah Mays ’20, longtime president of Morehouse College, and remembered as “the schoolmaster” of the Civil Rights Movement.