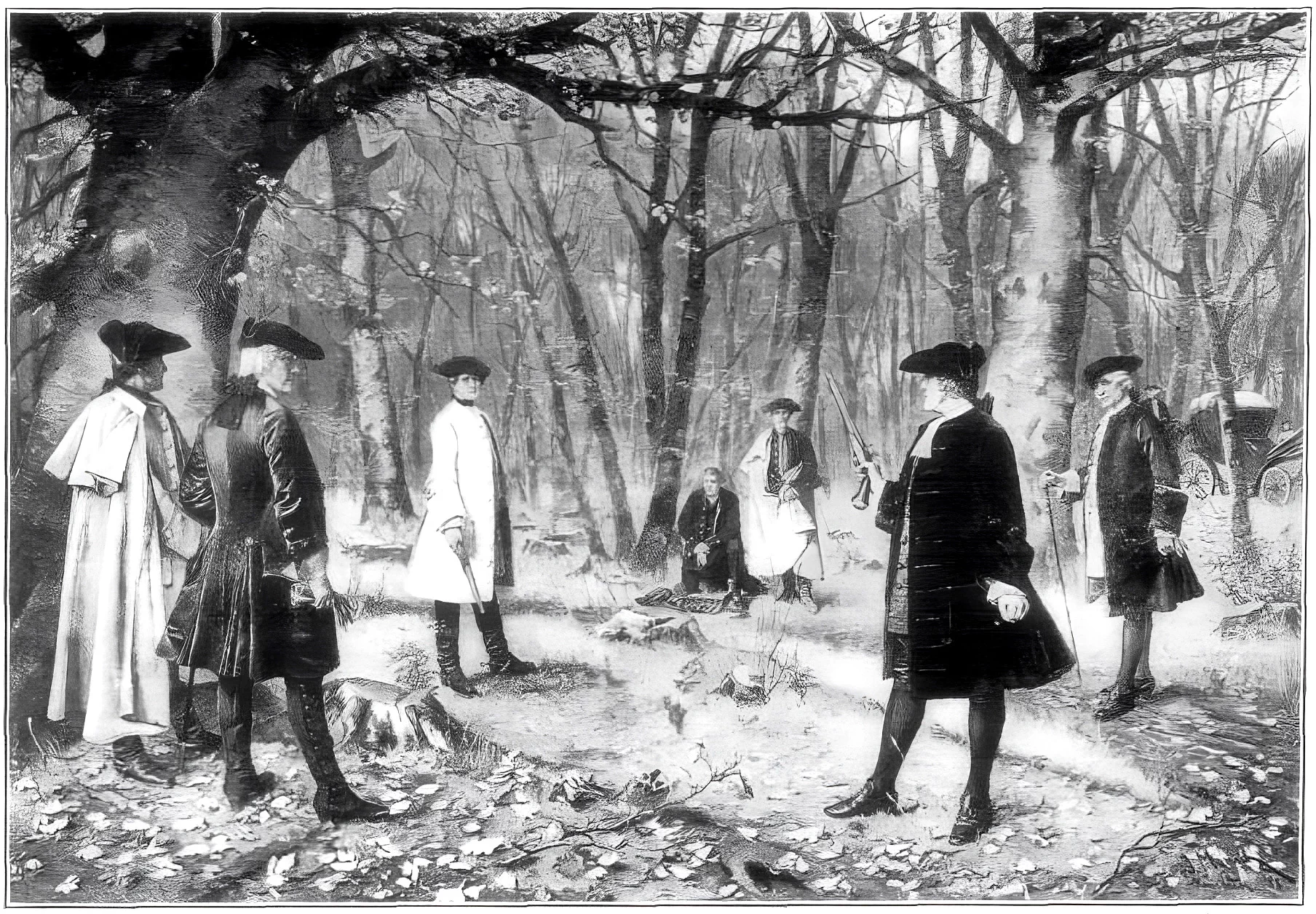

In April 1804, a newspaper published a scandalous letter alleging that Alexander Hamilton had publicly called Aaron Burr “a dangerous man,” even “despicable.”

That letter, published 220 years ago today, April 12, set into motion events that ended with the infamous pistol duel of July 1804, leaving Hamilton dead and Burr’s political career moribund.

Even before the musical Hamilton came onto the scene, the Burr-Hamilton duel left most people figuring that pistol duels were both deadly and irrational. Still, even as they faded away in the North, pistol duels continued to be common in the U.S. South in the decades before the Civil War.

Now we have an idea why: pistol duels served a purpose in the antebellum South.

That’s a theory, plus startling facts, put forth in a scholarly paper co-authored by Bates Professor of Economics Paul Shea, “Lethality and Deterrence in Affairs of Honor: The Case of the Antebellum South,” in the journal Rationality and Society.

Shea’s coauthors are Tom Ahn, an assistant professor of economics in the Department of Defense Management at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, Calif., and Jeremy Sandford, a former staff economist with the Federal Trade Commission and now with Compass Lexicon Inc.

To develop their theory, the authors use game theory, an understanding of 19th-century firearms, and a deep dive into historical newspaper accounts. The team also employed Emma Patard ’26 of Montreal as a research assistant. “She scoured old newspapers to create a database on 18th century duels,” says Shea.

So let’s get to the questions. First, why did duels remain popular in the U.S. South even as they faded in the North?

It’s easy to look back and call the duels barbaric and/or just plain stupid. But here, hindsight isn’t 20-20. Dueling had persisted for thousands of thousands of years in different societies. “You can find this all over the world. So it might not be something you would want in society, but there was probably a reason for it,” Shea said.

The antebellum South “did not have well-developed legal institutions,” explains Shea, “so you need something to settle public disputes” related to slander, libel, or other public transgressions. “Duels were a way to mitigate bad behavior, albeit violently.”

In fact, says Shea, “the institution of dueling actually seemed to work reasonably well to deter reputational damage. If you say something horrible about me, the fact that I am willing to risk my life — even if it’s a low risk — was seen as a kind of cleansing of reputation. In the absence of a court system that functioned the way we think of a court system, it did a reasonable job of deterring bad behavior in the antebellum South.”

Next question: Why was the practice of facing off with pistols at a relatively short distance not particularly fatal? Indeed, the risk of death from a duel was low, only about 7 percent.

That’s because participants mostly used antiquated and inaccurate weapons. “Dueling pistols were fancy but really ceremonial,” said Shea. The pistols, though exquisitely made, were smooth bore, not rifled, which meant that bullets were prone to tumbling in flight, reducing their accuracy. They were short-barreled, thus harder to aim.

This is where game theory comes into play. The pistols’ inaccuracy helped make the “game” of dueling worth engaging in. “If the premise is that dueling is a quasi-legal institution to remedy a conflict, it would be a problem if the outcome is based on who’s a better shot,” explains Shea. “If these weapons are so bad that they’re essentially random, then it levels the playing field” making a duel a reasonable option to solve a dispute.

On the other hand, the authors note that there had to be some threat to life and limb for duels to serve their social purpose. “The deterrent effect of dueling depended on the probability of death being neither too high nor too low,” the authors write. “Were dueling too safe, the institution’s public acceptance — and thus its usefulness — may have diminished.”

As an example of a non-fatal pistol duel that served its purpose, one can look at the duel between Secretary of State William Clay and U.S. Sen. John Randolph. The duel seems inept and nearly comical, yet it put an end to a dispute between the two.

According to one account, “Clay and Randolph were frenemies who, more often than not, were teetering on the cusp of a brawl.” In 1826, Randolph called Clay a “blackleg,” a card cheat. A duel was arranged for April 8, 1826, on the Virginia side of the Potomac River. Here’s a play-by-play of the five shots.

- Shot 1, by Randolph: A misfire even before the duel even starts.

- Shots 2 and 3: Clay and Randolph both miss.

- Shot 4 and 5: Clay’s shot puts a hole through Randolph’s coat. Then, Randolph points his pistol skyward and fires, ending the duel. The disputants shake hands, and Randolph quips to Clay, “You owe me a coat.”

Shea and his coauthors came up with the idea of looking into antebellum pistol duels years ago when they were all on the faculty at the University of Kentucky.

Chatting on the way to lunch one day, Shea remarked his wife, who is a lawyer, had to pledge that she had never engaged in a pistol duel in order to be admitted to the Kentucky bar. “Well of course, this was a huge problem because my wife has pistol duels all the time,” Shea said with a laugh. “We were all Northerners, so it struck us as absolutely bizarre.”

Like so many other scholarly investigations, their research began with a simple question, “What’s up with this?” As they dug deeper, “we realized there was relatively little on duels and what was out there was pretty poor. And so we decided that there was actually a paper here. And so it was half fun, but then it got serious.”

Shea’s field is macroeconomics, and his recent papers include “Housing, Endogenous Growth, and Household Leverage” in Macroeconomic Dynamics, which looks at the interplay between household borrowing, access to credit, and economic growth.

So a paper about 19th-century pistol duels might seem off the mark (so to speak), in terms of Shea’s overall scholarship, but it’s an example of how academics from different disciplines (coauthor Ahn is an empirical micro economist, and Sandford has game-theory expertise) can do collaborative research.

It’s also a reasonable example of what economics is all about.

“Fundamentally, economics is a study of human behavior using certain tools. You can be tempted to say, ‘Well, that was stupid. Why are people doing that?” Yes, maybe individuals do stupid things. Yes, maybe societies do stupid things too. But economics tells us that there’s usually some rationale.”