A few days ago, I was driving to the college, listening to the radio, and there was a story about how corporations have pulled back from celebrating Pride.

In particular, the story recounted Target’s discontinuing of its Pride-themed children’s clothing line, the elimination of Pride displays from many though not all stores, and the shifting of Pride-themed merchandise to online availability only.

About Stephen Engel

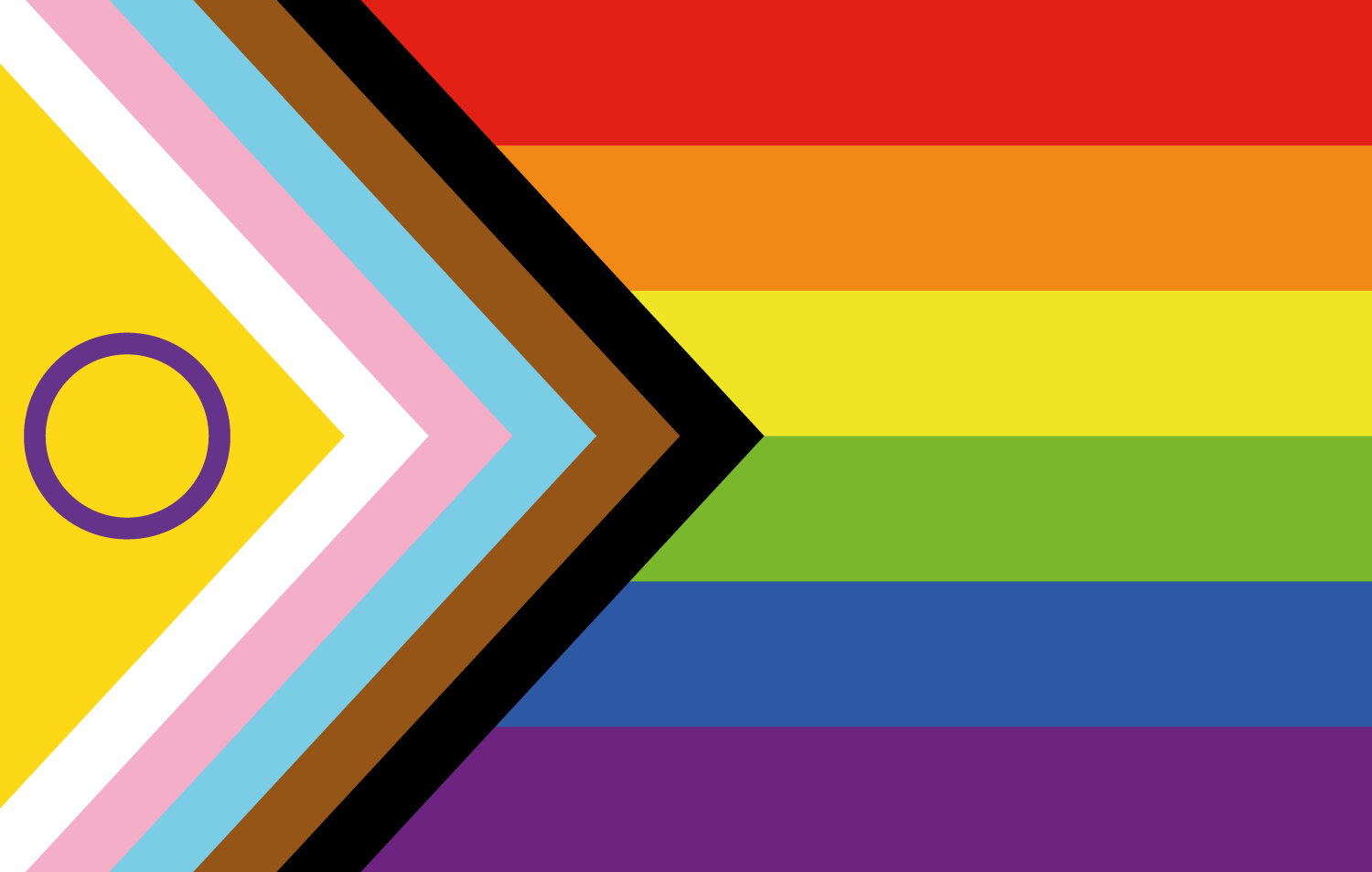

Professor of Politics and Associate Dean of the Faculty Stephen Engel offered these remarks at the raising of the Intersex-Inclusive Progress Pride Flag at Garcelon Field on June 13. His current research looks at whether discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity constitutes a violation of the Constitution’s 13th Amendment.

Similarly, Bud Light had pulled back from Pride-based marketing, and the explanation was that general marketing for Pride was costly; it provoked backlash.

While that might make us think about a broader critique of late-stage capitalism or about how we should not conflate consumerism with political recognition and equal treatment, the story also included the comment that many companies know how to do niche marketing, so that queer consumers would still have access to queer- and pride-themed products, but that other consumers wouldn’t, and isn’t that great.

No, it is not great, I think, for at least two reasons. First, when I was a closeted 17-year-old, seeing some pride gear at a store on public display would probably have brought me some joy or, if not joy, at least carried the notion that I wasn’t alone even if I knew no one who was out at the time.

Second, targeted messaging about Pride to those who are in the community, who are in the life, isn’t actually the point of Pride. For me, Pride isn’t about, or isn’t only about, a time to celebrate my queerness, my identity, with my community. And it’s not about, or isn’t only about, as a recent meme has suggested, going to a parade so I can get smacked in the head when someone from the Bank of America float throws a rainbow-colored Bank of America-branded pen at me.

Pride is about demanding recognition, it is about demanding rights, and it is about taking up space and responsibility precisely among the people who don’t want to see you. Pride is the opposite of niche marketing.

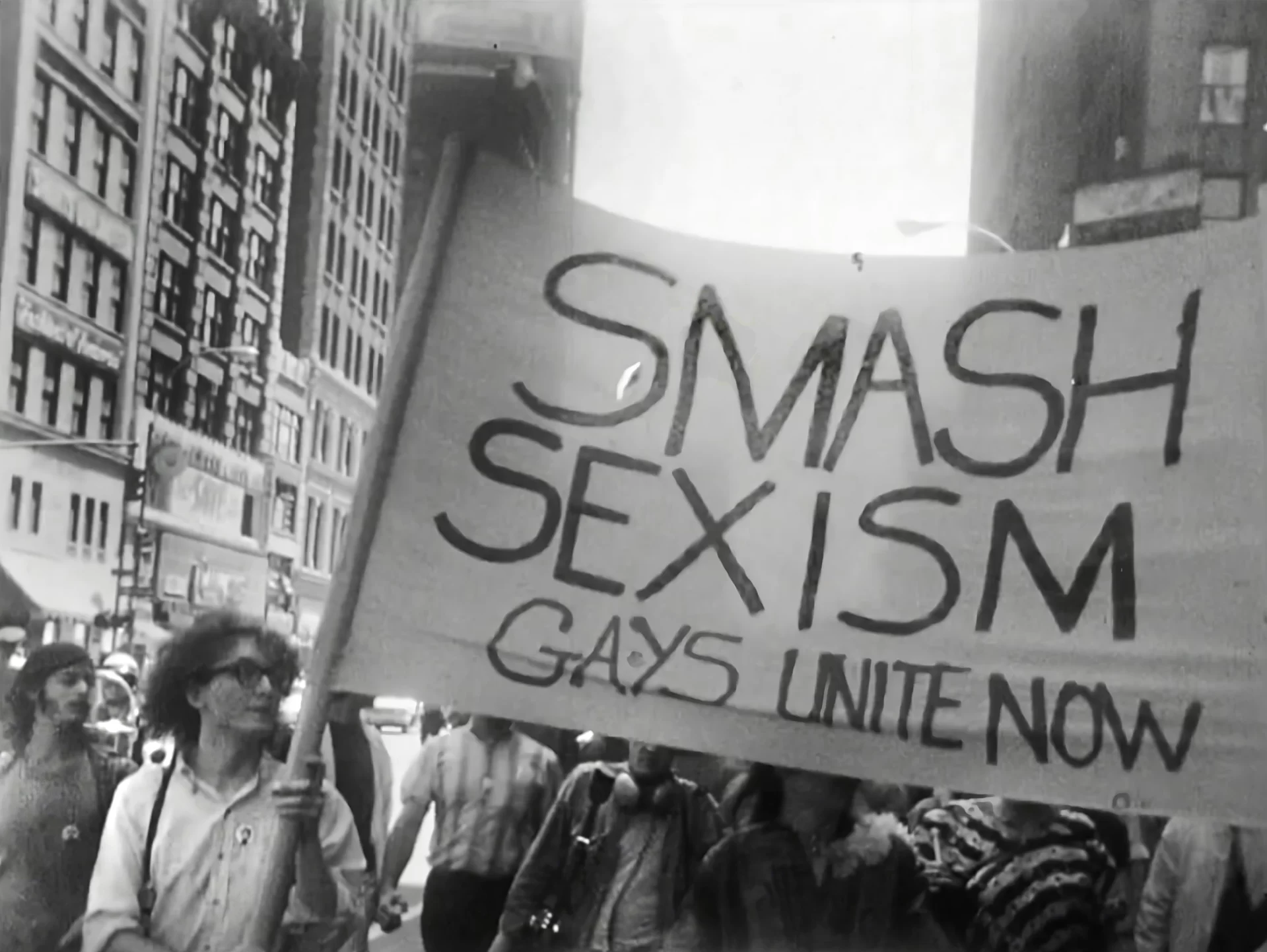

What we think of today as Pride celebrations in June grew out of the Christopher Street Liberation Day March of 1970, a commemoration of the Stonewall Riots that took place in New York City on June 28, 1969.

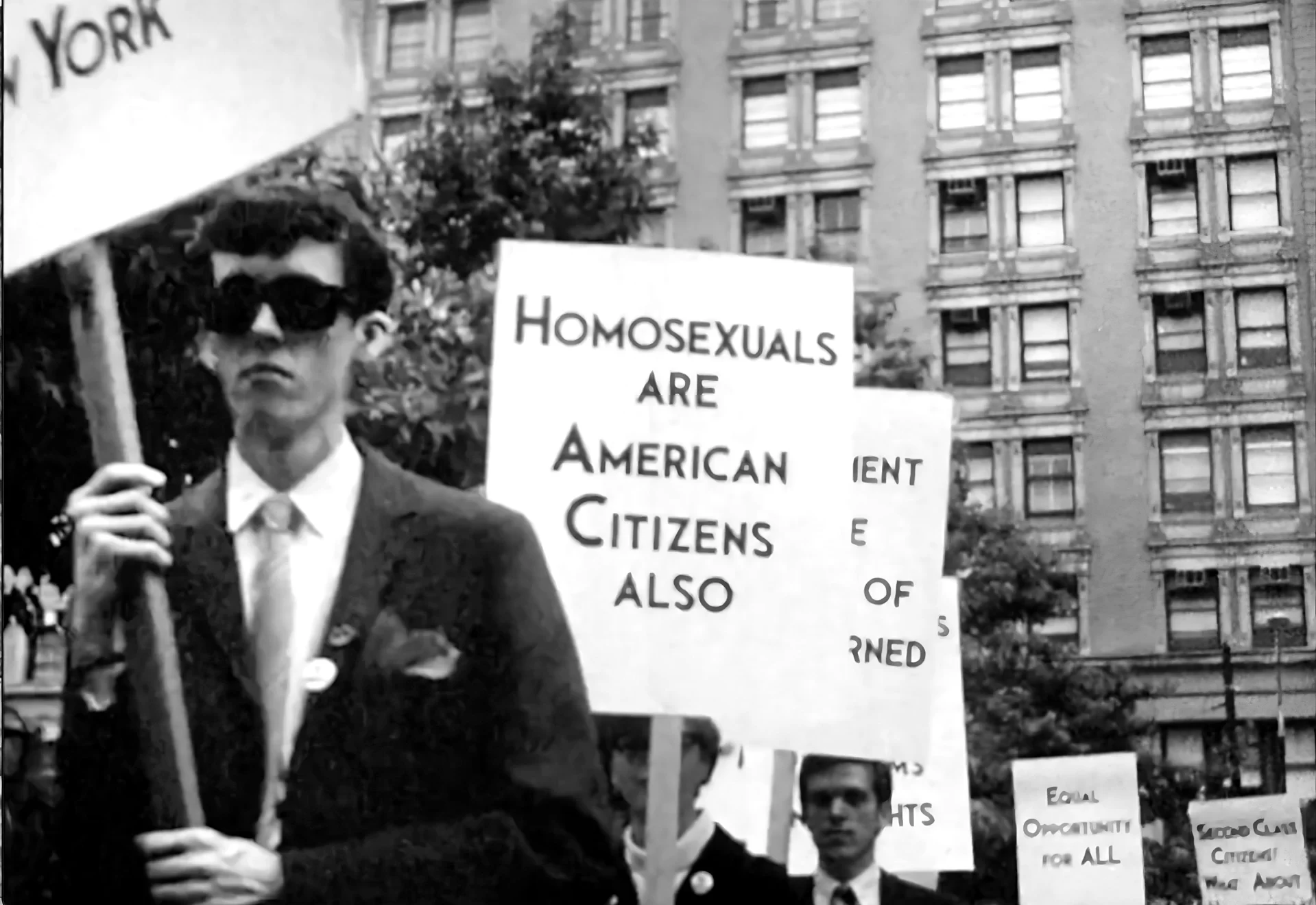

But it is also important to remember that, as I teach in my classes, Stonewall is by no means the start of LGBTQIA+ political activism. Indeed, the Christopher Street Liberation Day March was based on the Annual Reminder Day pickets, which were held on July 4 in the early and mid 1960s, organized by the Eastern Regional Conference of Homophile Organizations that was made up of the Daughters of Bilitis of New York, the Mattachine Society of New York, and the Janus Society of Philadelphia.

And those pickets — as a political strategy — drew upon the tactics of African American civil rights mobilization, upon second-wave feminist theory and action, and upon a rich history of labor activism and protest. Pride celebrates all of those historical connections and shared paths.

As we take a moment to remember that history and those points of connection among and across communities as well as shared and distinct identities, we should also take stock of what we forget. If Pride lands in June to commemorate the Stonewall Riots, let’s also be sure to remember the Compton’s Cafeteria riots in San Francisco three years before Stonewall when trans women stood up against police violence.

Let’s be sure to remember when queers took a stand against state violence and discrimination at Cooper Do-nuts in Los Angeles in 1958. Let’s remember when in 1961, a gender non-conforming Black queen, Josie Carter, stood their ground to protect a bar in Milwaukee from men trying to physically destroy this gathering place. Let’s remember when over 200 people picketed in front of the Black Cat tavern in 1967 in Los Angeles to protest police harassment of our community.

Remembering that long history of protest — of standing up to be seen — and remembering that Pride is as much a celebration as it is a political riot is more necessary than ever as our communities are confronted with hostile state governments as much as with cowering and cowardly corporate partners.

The rights and value of our community, of ourselves, have been stripped away by state governments that have passed bans on gender-affirming care, that have banned books and even the ability to speak our truths publicly, and that have sought to divide our communities by threatening the most vulnerable among us while simultaneously elevating those within our community who are already privileged.

So, as we mark Pride 2024, some aspects of our shared experience may seem bleak or challenging, but they are no more so than what our predecessors faced. We do well to remember how they were proud, how they fought back, and how they celebrated their queerness and their community, to make better lives for us.

And, Pride reminds us to take up that challenge, and to be visible not only within our own community, within our own niche, but to everyone.

Faculty Featured

Stephen M. Engel

Professor of Politics