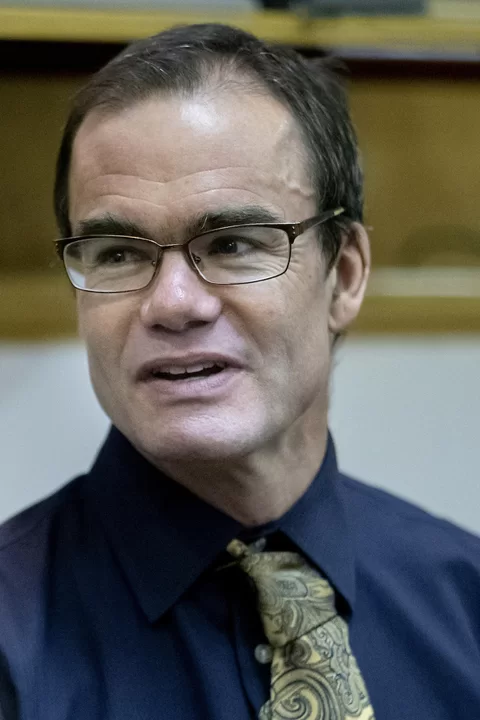

Joe Hall, an associate professor of history at Bates whose course offerings include Native American history broadly and also specifically — that of the Indigenous people of Maine — got a call for help in early August. His expertise was needed to correct, or deepen, the record about how two Maine landmarks came to be.

Both stories covered the history of places as they related to European settlers. And that caused concern for members of a group Hall belongs to, the Pejepscot Portage Mapping Project, which has been working to record the history of the Brunswick area as home to Indigenous people.

Faculty in the News: Bates Bylines

Associate Professor of History Joe Hall‘s principal scholarly interests focus on Native American interactions with Europeans during the colonial period.

Concerned that the stories recounted history within a vacuum, leaving out the stories of the Wabanaki people, they asked Hall to write to the papers’ editors to provide more context.

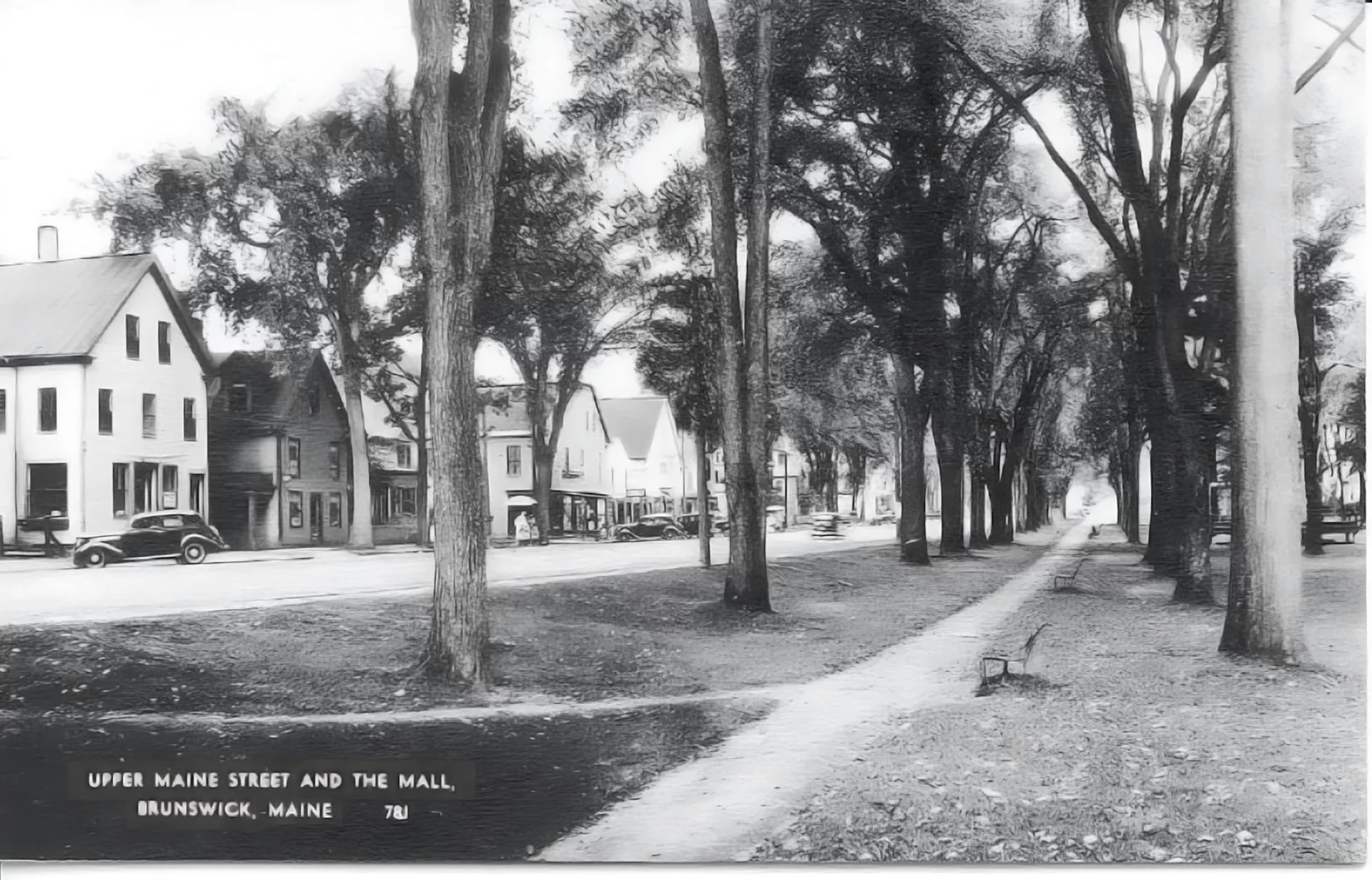

Two stories about the development of Brunswick had just appeared in the Portland Press Herald and Times Record, intriguing pieces explaining how a Brunswick swamp had been developed into a lush town green in the early 19th century, and why one of the town’s other claims to local fame, its broad Maine Street, is so majestically wide (according to the author, to create a buffer “in case of an ambush”).

Hall, the volunteer historian of the group, quickly wrote two responses and within days of the first story (the one about the Brunswick Mall, as the town green is known), his guest column, “A deeper layer to origins of Brunswick’s Mall,” appeared on the papers’ sites. (His second response, about the origins of Maine Street, has not yet run.)

For starters, the colonists found that swampy area unsightly and inconvenient — the cattle they had sold at the market on the shores of the Androscoggin River and were taking to Maquoit Bay to be loaded on ships for trade kept getting bogged down in the mud. Plus, mosquitos abounded. But for the people who came before them, who had walked the route of Maine Street before it became a street, that swamp had true benefits, Hall wrote:

In the centuries before Brunswick, Wabanaki lived in the area, fishing at Pejepscot Falls, farming along the banks of the Androscoggin, gathering blueberries on the pine barrens, and digging clams at Maquoit.

The swamp also provided for these residents and travelers. It fed a reliable stream of water that saved thirsty Wabanaki the trouble of a steep descent to the Androscoggin. It grew cattails, which have edible roots, leaves that can be woven into mats or bags and downy seed pods that can wrap infants for warmth. It grew fiddleheads, which are the spring shoots of ostrich ferns, providing food at the end of long winters. To be sure, it also bred swarms of mosquitoes that plagued Wabanaki as well as later colonists, but a swamp is more than its nuisances.

The Pejepscot Portage Mapping Project is working to create a digital map of the Brunswick area as the Wabanaki people used it. For the last three years, Hall has been contributing his historical perspective to the group effort and finding it deeply rewarding. The group includes non-Indigenous and Wabanaki people from the Brunswick area who are interested in highlighting the Wabanaki history of the area.

“It’s a really interesting mix of people,” Hall says. “Which is a fun way to do scholarship. To be involved is really gratifying. I feel like I’m doing something that is not going to end up on a shelf. You won’t find it in a library. It’s not some big scholarly thing, but I hope people are going to read it and think, ‘Oh I didn’t realize that was part of the story.’”

These places, including Maine Street itself, are “fundamentally defined by Native history,” Hall says. It’s true that Maine Street was built “twelve rods” wide to avoid ambushes by Native people. But they were being blocked from using their traditional fishing grounds by settlers, who built a fort there to claim it.

Moreover, Maine Street also travels the same path the indigenous people used as a portage, walking from the falls to the waters of Casco Bay carrying their canoes. “There’s a Wabanaki foundation to all of this.” (On Oct. 6, Hall will participate in a historical walking tour centered around that portage with the Walk for Historical and Ecological Recovery, which is in the process of completing seven guided walks of old Native areas in Maine this year.)

Because the Pejepscot Portage Mapping Project seeks to highlight Wabanaki history of the region, the group has also consulted with a variety of Wabanaki educators over the years. Hall and his partners have found the conversations vital for framing their work. They have learned important information, and they have also gained a sense of which lessons Wabanaki find most meaningful.

The project is educational, but who knows where raising awareness might lead. “It’s a little humbling to feel like my partners and I are part of something with an unknown destination or end-point. Wabanaki history is interesting, sure, but what does it mean? Reparations in the form of giving land back? This work raises hard questions, fundamental questions. There’s a reason why it’s a lot easier if colonial peoples like me don’t know that Maine Street was a portage, and that an old swamp was actually a place of sustenance, as opposed to just an eyesore where cows got stuck in the mud. Which is what a newspaper article I read from 1853 was saying. Basically, ‘poor cows.’”

Earlier: In 2019, during the celebration of Auburn’s 150th birthday, Hall wrote a guest column for the Sun Journal, addressing Native history within a commemoration of the era of settlers.

Mary F. Pols

Senior Director of Communications & Editorial

Bates Communications and Marketing Office

207-786-8248