The vote by the Bates faculty, 40 years ago in the Filene Room in Pettigrew Hall, wasn’t even close: 58–27 in favor of making the submission of SAT scores optional for admission.

It was the vote heard ’round the country. Within two weeks, thanks in part to a major New York Times story that was picked up by newspapers around the nation, Bates had entered into, and would ultimately become a leader of the national conversation about the value of standardized tests in college admission. Today, around 80 percent of U.S. four-year colleges and universities do not require ACT/SAT for admission.

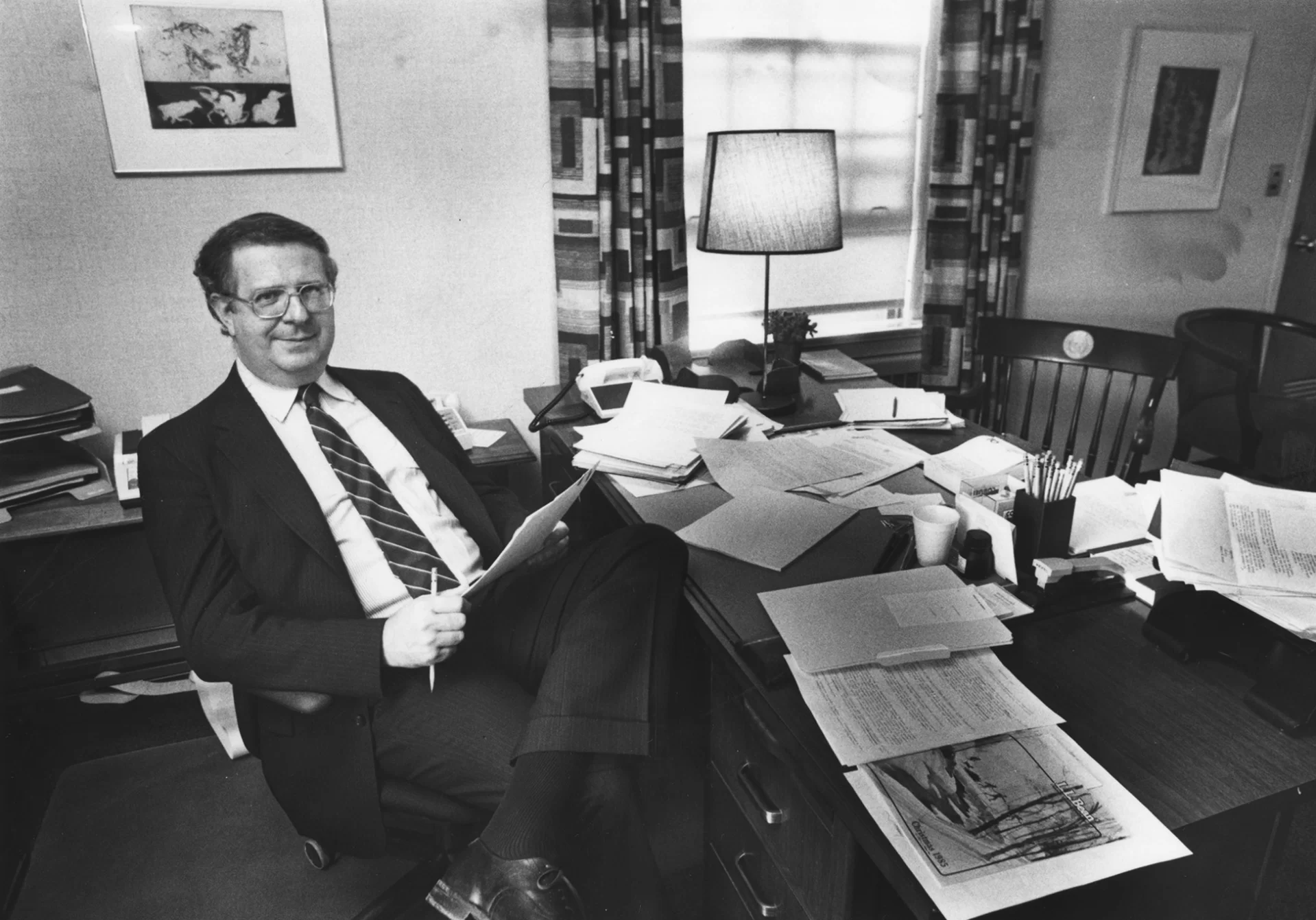

Six years after the 1984 vote, then-Dean of Admission and Financial Aid Bill Hiss ’66 called the vote “a bold move and one we haven’t regretted.” Entering its fifth decade as a test-optional pioneer, Bates still has no regrets, says Leigh Weisenburger, vice president for enrollment and dean of admission and financial aid.

“Standardized tests and a student’s subsequent scores are rooted in inequity,” she says. “Our test-optional admission policy removes a barrier for many talented and promising students, and we see it as a natural extension of our progressive history and mission dedicated to access and inclusion.”

Followup studies over the years have supported what Bates believed to be true in 1984. Standardized tests are no better than a student’s high school grades as a measure of academic potential. At worse, they can filter out and discourage talented students who are already underserved by U.S. higher education.

In retrospect, the 1984 decision to go test-optional seems obvious — a slam dunk. But thanks to a first-year reporter’s account for The Bates Student, the only record of the discussion, we know that there was staunch opposition to the proposed legislation on that Monday afternoon in the Filene Room.

Specifically, two titans of the Bates faculty were firmly opposed to making SATs optional. One was Dean of Students Jim Carignan ’61, who had joined the history faculty in 1970 and was appointed dean of students about a decade later by Bates President Hedley Reynolds. The other was Carl Straub, who had joined the Bates religion faculty in 1965 and was named dean of the faculty in 1974.

Covering the October faculty meeting for the Student was a cub reporter, Howard Fine ’88, whose story for the Student included telling quotes from Reynolds, Carignan, and Straub.

With a formidable disdain for flash over substance, Straub said that a decision to drop the SAT requirement had nothing to do with education. “It is more a marketing issue. I see no evidence that convinces me that the proposed [legislation] will increase the number or quality of applicants.”

In his quoted remarks at the meeting, Reynolds agreed that the legislation had a marketing angle, but one “which will, in the long run, bring more good students” to Bates. Indeed, the prospect of good publicity for Bates was a selling point, Fine recalls. “There was an awareness among the faculty that if SAT scores were made optional for admission, it would garner national attention since so few schools around the country had taken that path.”

Meanwhile, Carignan argued that “moving away from the SAT signals a retreat” from an important measure of academic strength at a time when “we are making real strides in strengthening our [application] pool and advancing the image of the college as academically strong.”

Professor Emeritus of Psychology John Kelsey was in the room that day, and he recalls agreeing with some of his colleagues that SAT scores were helpful predictive tools. Forty years after the vote, he’s aware of the privilege of that perspective. “As majority white and male academics, we had the bias that SATs measured something quite important: ‘What was your SAT score?'”

Kelsey has long experience as adjunct application reader for Bates Admission. While not recalling his own vote that day, he does remember the “highly persuasive argument that SATs were highly correlated with socioeconomic status, and thus biased against a variety of groups we all wished to attract to Bates.”

The fall of 1984 at Bates was a typically busy time on campus in light of local, national, and global events. There was the visit to Bates by Lisa Birnbach, author of The Official Preppy Handbook, to do a TV segment for NBC’s Today show, then hosted by Bryant Gumbel ’70.

There were incoming ripples from the looming Reagan–Mondale presidential election. On campus, a mini-controversy erupted over the two state liquor inspectors who, posing as construction workers, raided a Milliken House party.

But the drama of the SAT vote rose above them all. “It was regarded as a big deal,” recalls Fine, who went into journalism after graduation and is a longtime reporter with the Los Angeles Business Journal.

Despite the opposition from Carignan and Straub, the legislation passed easily. Kelsey described the faculty sentiment this way: “We agreed to do a kind of experiment. And I judge that experiment to be largely a success.”

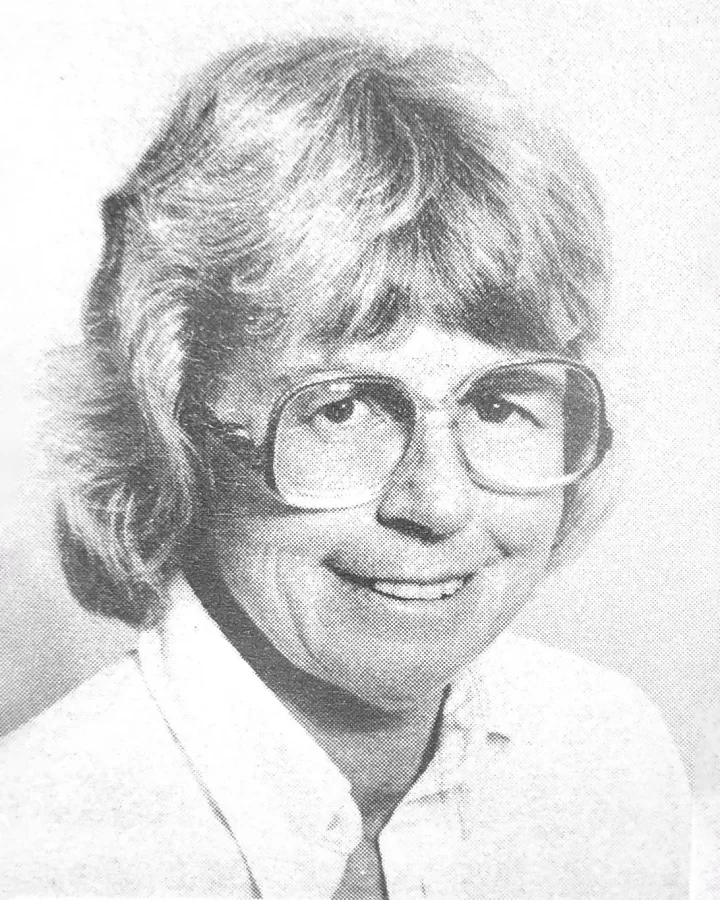

One reason the legislation sailed through, perhaps, is that the faculty Committee on Admissions and Financial Aid, chaired by Anne Thompson of the English department, had done its work.

Supported by Hiss, whom Reynolds had plucked from the faculty of nearby Hebron Academy in 1978 to lead the Bates Admission team, the committee presented a compelling 20-page report to the faculty, the result of five years of research. (Drake Bradley, Dana Professor Emeritus of Psychology, made major contributions to the college’s statistical research before the vote and in follow-up studies.)

The report presented what is now a consensus in the college admission world: that SATs are “not critical to making good admission decisions” and that the use of standardized tests like the SAT presents a series of ethical issues. Those include troubling correlation of test scores to family income; the rise of SAT coaching, again benefiting wealthier students; and how high school teachers were beginning to alter their curricula to, in the words of one high school teacher, “to teach kids how to take the [SATs].”

The Report

Read the seminal report prepared by the faculty Committee on Admissions and Financial Aid that helped to convince the faculty to vote to make SATs optional in 1984.

After the vote, a Bates Magazine story noted that Bates students with weaker test scores, including minority students, rural students, and poor students, “have made great contributions once enrolled at Bates.” That fact, according to Thompson, “cast a great deal of doubt on the fairness of using the tests for admission purposes.”

The report included results from a questionnaire sent to guidance counselors at 95 high schools, which indicated that SATs were hurting the college’s efforts to build a larger and stronger applicant pool. Increasingly, students were using a college’s mean SAT scores, as published in guidebooks, to opt out from applying. If a student’s score was below the mean, they didn’t apply (too hard to get in); if their score was above the mean, they didn’t apply (too easy to get in).

“By not requiring SATs,” the report concluded, “Bates could encourage a greater diversity of students to apply [and] who are capable of succeeding at Bates, but who, for cultural or financial reasons, have not scored well and are currently being discouraged from applying.”

In 1990, Bates dropped all standardized test requirement, including achievement tests. In a followup article in Bates Magazine that year, Hiss noted that the academic strength of a study body isn’t a measure of who is admitted, but who applies. And when Bates dropped the SAT requirement, applications jumped by a third, and the quality of the application pool remained high.

(Growing the applicant pool also had the additional benefit of improving Bates’ selectivity, as published in college guidebooks, a hoped-for result of an optional-SAT policy that Kelsey recalls being in the air and was also noted in Fine’s reporting in fall 1984.)

Sharing his thoughts recently, Hiss said that the growth of the pool meant success at meeting a charge from his boss. “When I was hired, Hedley, in our first conversation, gave me a one-sentence charge, which I remember verbatim and have many times quoted to our staff and others over the years: ‘Take the applicant pools up and down the social and economic ladders, and spread out geographically.’

“He thought we were too narrowly middle class and too narrowly New England. He was right on both counts. So the optional-testing decision, six years later, was one step among many in having Bates become a national college and then an international one, with a much more complex array of student backgrounds.”

The charge also reflected what Reynolds and others saw coming, a decline in New England’s share of the U.S. population. Expansion was a business decision in addition to an educational and mission-driven one.

By any measure, Bates in the 1980s was indeed growing stronger and expanding its reputation under Reynolds, whose focus was on enrollment, facilities, and, especially, support for the faculty, which took the shape of a near doubling of its size, strengthening academic credentials, and lowering the student-faculty ratio, from 15-to-1 to 13-to-1 (today it is 10–1).

And this might be a second reason that the Bates faculty responded positively to the SAT legislation: respect for Reynolds’ forward-looking leadership of the college.

A former history professor and dean at Middlebury, Reynolds “understood faculty governance, he understood the intellectual life, he understood the importance of faculty scholarship, and faculty support — everything,” recalled Hiss in a 2005 oral history for the Muskie Archives and Special Collection Library. Compared to prior Bates leaders, he was “far more of a visionary about Bates, far more willing to change Bates in profound, systemic ways.”

“This is not the time for rigidity,” Reynolds said. “It is not a time for the college to stand proudly looking backward.”

A day after the faculty vote, Hiss was in Boston with Admission colleague Wylie Mitchell (later to become Bates’ admission dean), attending the annual conference of the National Association for College Admission Counseling (NACAC).

There, the pair met with Ted Fiske, education reporter for The New York Times, who had just begun what would become the highly influential Fiske Guide to Colleges. “We had lunch with Ted, and he broke the story,” recalls Hiss. On Oct. 9, with Bates prominent in the lead paragraphs and throughout, Fiske’s story ran in the Times under the headline, “Some colleges question usefulness of SATs.”

Meanwhile, The Bates Student had broken the news four days earlier, in its Oct. 5 edition. Fine’s story offered perhaps the most telling quotes about how Bates rolled under Reynolds. “This is not the time for rigidity,” Reynolds said. “It is not a time for the college to stand proudly looking backward.”

Today, around 80 percent of all four-year colleges and universities have moved to some form of optional testing. Many have been influenced by various follow-up studies conducted by Bates, often supported by members of the Bates staff and faculty, capped off by a 30-year study co-authored by Hiss and Valerie Wilson Franks ’98 in 2014.

“It’s been a 40-year commitment for me,” said Hiss, who retired from Bates in 2012. “But maybe the larger story is 40 years of Bates and Bates people doing the work to make the college a major force in changing American definitions of promise and intelligence.”