In a recent episode of Hidden Brain, titled “Sitting with Uncertainty,” Associate Professor of Psychology Michael Sargent’s research on attitudes toward crime and punishment got a shoutout — and a ringing endorsement — from the week’s guest, author and scholar Dannagal Goldthwaite Young.

The podcast’s host, Shankar Vedantam, who received an honorary degree from Bates in 2023, was interviewing Young, a professor of political science and communication at the University of Delaware, about how our widely-ranging capacity for ambiguity impacts our lives. This psychological trait, Vedantam said, “plays a surprisingly large role in shaping our behavior, perspectives, even our political beliefs.”

One of the traits that relates to the human capacity for uncertainty is a “high need for cognition,” an area Sargent has studied. This isn’t about intelligence, but more about an individual’s need to think, which connects to their openness to uncertainty, or life’s gray areas.

Faculty in the News: Scholarship in the Spotlight

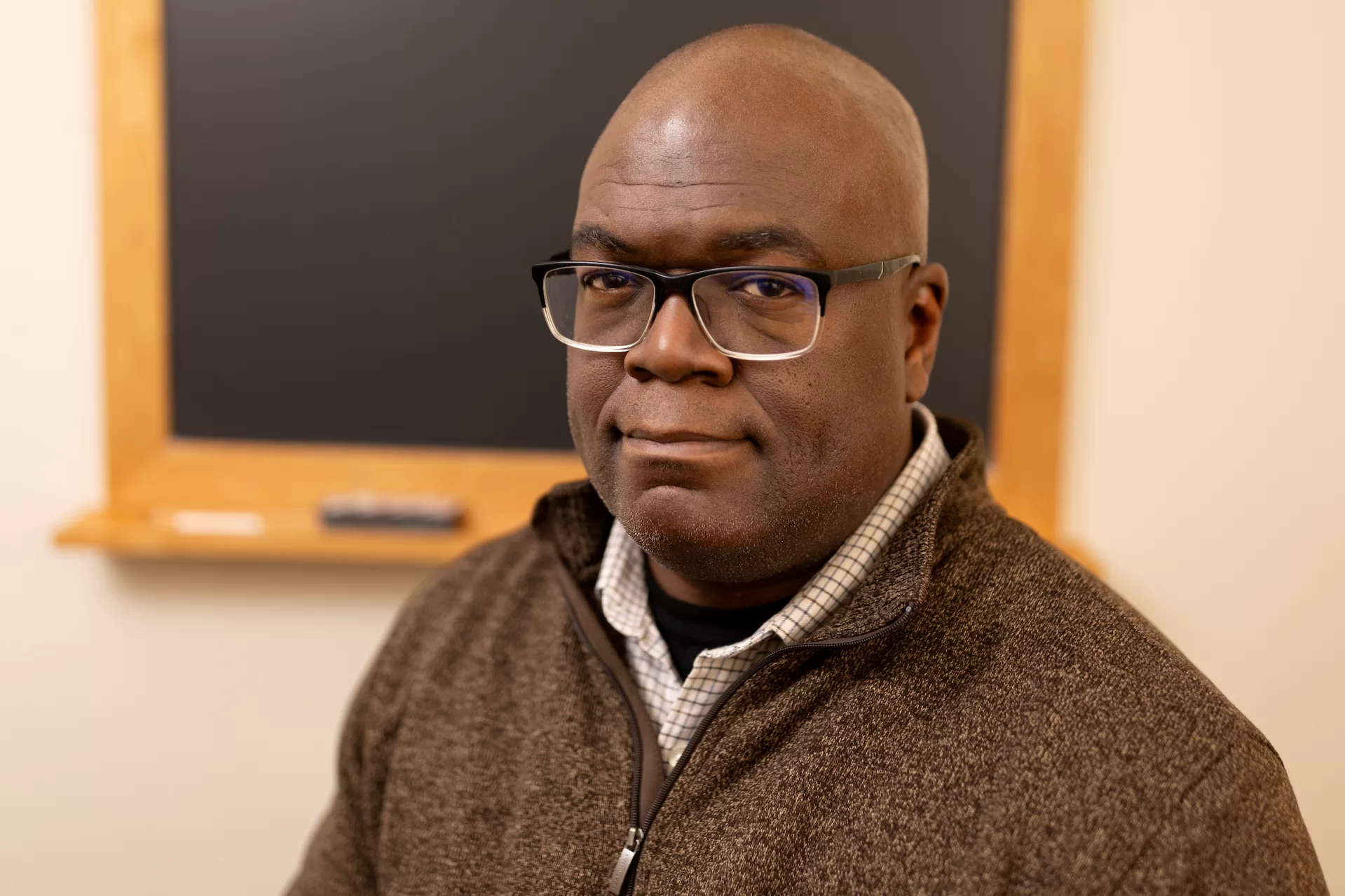

Associate Professor of Psychology Michael Sargent is a social psychologist by training, but with interests in political psychology. Most of his research focus is on the ways that people’s collective identities relate to how they think about politics, especially their opinions toward policies.

About halfway through the interview, when Vedantam asked Young how our political beliefs might be shaped by our differing levels of need for cognition, she responded that “there is some wonderful work from political psychology that looks at the trait ‘need for cognition,’” referencing how “work by Michael Sargent showed that people who were highest in need for cognition…tended to be the least supportive of highly punitive measures in response to criminals or in the context of crime.”

Young noted that Sargent found that “people higher in need for cognition were probably more motivated to consider more complex ways of attributing responsibility for why individuals would have engaged in these criminal acts in the first place.”

In other words, said Young, “a high need for cognition allows people to think beyond simple causal mechanisms of bad-person-does-bad-thing and to think perhaps more systemically about other factors that may have been responsible for that criminal act in the first place.”

After this shoutout on the popular podcast (Hidden Brain is estimated to be downloaded 2 to 3 million times a week), Bates News checked in with Sargent to find out more.

Bates News: Young took a more extensive look at your research in her 2019 book Irony and Outrage: The Polarized Landscape of Rage, Fear, and Laughter in the U.S. (Her most recent book is Wrong: How Media, Politics, and Identity Drive our Appetite for Misinformation, released in 2023.) Have the two of you ever crossed paths, outside of bibliography?

Michael Sargent: I don’t know her, and it was a total, pleasant surprise to learn that she cited my work, especially because she described the work with perfect accuracy.

BN: That study of yours, “Less thought, more punishment: Need for cognition predicts support for punitive responses to crime,” was published in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin in 2004. Can you give a little background on how it came about?

MS: This was a case of serendipity — some very good luck. I had actually collected some survey data for an unrelated purpose, and had included the need for cognition questions and the questions measuring punitiveness as filler items. In other words, their sole purpose was to disguise the focus of the study. I just decided to explore the data, and discovered that there was a negative correlation: as need for cognition went up, punitiveness went down.

Naturally, my next impulse was to collect data in a new sample to try to replicate the effect, so I could be relatively sure that the first finding wasn’t just a fluke. To my delight, the effect replicated, and it replicated once again in a third study that also shed light on why the need for cognition was having the effect it seemed to have.

As I explain in the article, attributional complexity seems to be the mechanism. People high in need for cognition seem to gravitate toward relatively complex explanations for phenomena they observe, and the tendency to explain criminal action in complex terms, such as in terms of societal influence, tends to reduce one’s motivation to impose severe punishment.

As for how the article ended up in PSPB, that’s another example of good luck. I was going to submit it to a less selective journal, but I showed a draft of the manuscript to one of my former professors from graduate school — Jon Krosnick — and Jon advised me to aim higher and go for PSPB.

“Someone who is high in need for cognition is more likely to invest time in cognitively-demanding tasks, such as The New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle, and to do so even when they don’t have to.”

I’m lucky he gave me that advice, as the article was obviously accepted, and it’s probably gotten more exposure at that outlet than it would have otherwise. It’s a reminder that it pays to be lucky — lucky enough to have wise colleagues with whom one can consult. And it pays to be sure to consult with them.

BN: What’s your best translation for the term “high need for cognition” — is it really about enjoying thinking/contemplating?

MS: Need for cognition describes an individual’s cognitive motivation. It describes how much, or how little, a person enjoys engaging in effortful thought. Someone who is high in need for cognition is more likely to invest time in cognitively-demanding tasks, such as The New York Times Sunday crossword puzzle, and to do so even when they don’t have to, than someone low in the need for cognition.

Importantly, need for cognition is not descriptive of someone’s intelligence. Intelligence is about cognitive ability, but need for cognition is about cognitive motivation. To illustrate, one can be high in intelligence, but low in need for cognition, meaning that one is high in cognitive ability, but one doesn’t enjoy exercising that cognitive ability. As a professor, that prospect bums me out, but it’s very real.

BN: Do you think there has been a cultural shift around high/low need for cognition in the last two decades?

MS: That’s a great question, and it’s one to which I will plead ignorance, or at least a lack of sufficient expertise, and I’ll defer to anthropologists, or at least to bolder social psychologists than I am. But whether or not general levels of cognitive motivation have shifted, I will hazard a guess that technology has shifted in a way that adversely affects our capacity to engage in sustained, effortful thought.

Perhaps it’s a pedestrian observation, but the fact that the typical person (at least in the industrialized world) carries a computer in their pocket or purse that can ping us multiple times a day with text messages and social media notifications, probably gets in the way of the kind of concentration that’s characteristic of high “needcogs.” Whatever kind of shift we might call that, I think it can get in the way of high needcogs being high needcogs.

BN: You were one of the official faculty hosts for honorary degree recipients in 2023 when Vedantam was at Bates. Did you get a chance to talk brain science?

Sargent: Briefly, yes. I don’t recall what we talked about but it might have been implicit bias.

Faculty Featured

Michael Sargent

Associate Professor of Psychology