Thirty-nine years ago, even a hurricane couldn’t stay Jimmy Carter from a self-appointed duty: coming to Bates to dedicate a new archive in honor of his good friend, Edmund Muskie ’36.

As Hurricane Gloria roared up the East Coast in late September 1985, threatening to thwart the former president’s trip to Maine, Carter’s reaction was, basically, “bring it on.”

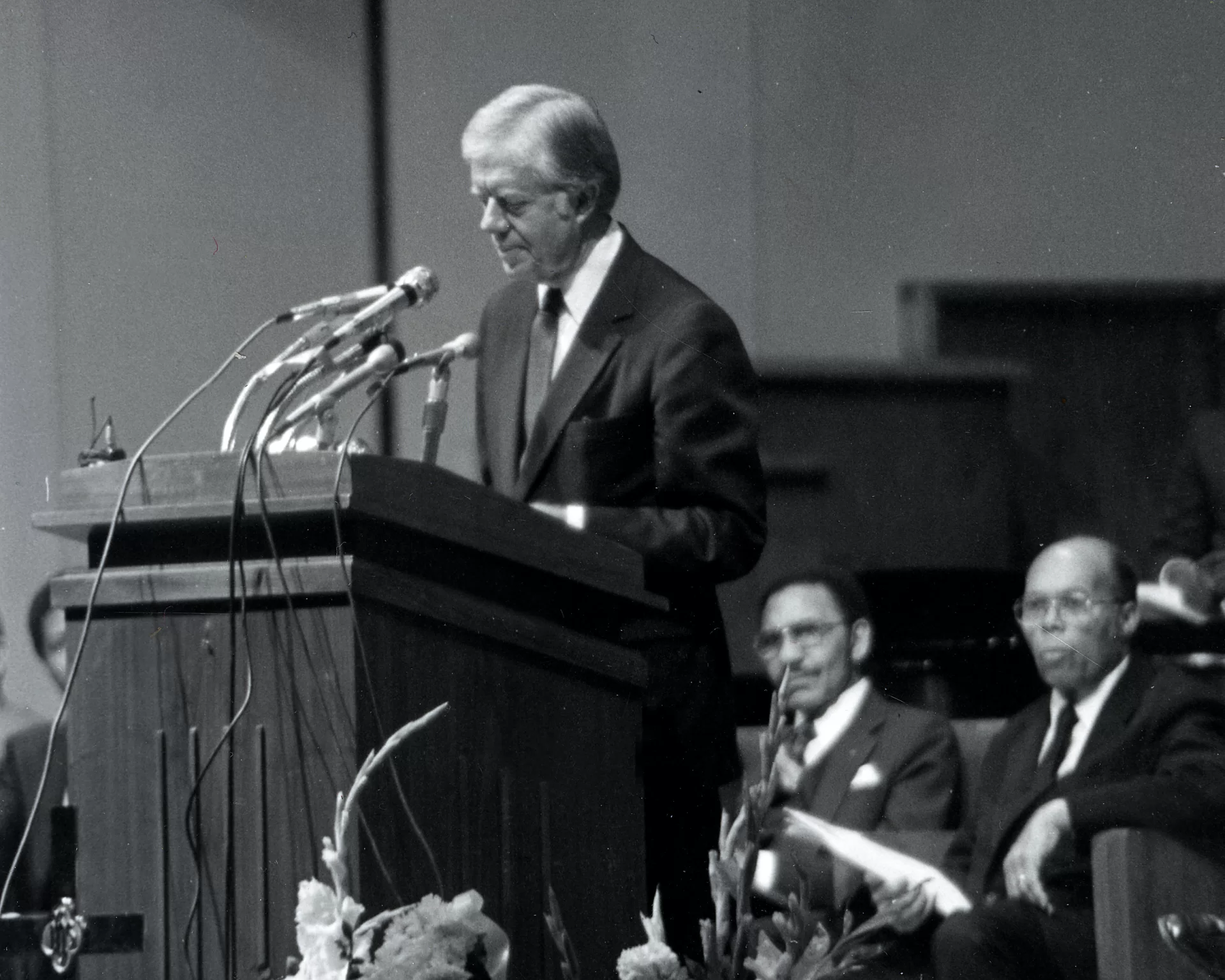

“Nothing short of an absolute national catastrophe…could have prevented my coming to Bates College,” Carter told an audience of more than 2,700 in Merrill Gymnasium on Sept. 28, 1985, during a dedication convocation for the official repository of Muskie’s papers, now known as the Edmund S. Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library.

Carter died today at age 100 at his home in Plains, Ga.

In 1985, Carter also used the occasional to speak warmly about another Bates friend, civil rights leader Benjamin E. Mays, Class of 1920, who had died a year earlier. “I want to thank this college for making it possible for Dr. Benjamin Mays to overcome the handicaps of white supremacy and racism to take his place among the prominent leaders of our nation and our world.”

In his address, Carter described Muskie, a deeply admired colleague and friend who served as Carter’s secretary of state from May 1980 to January 1981, as representing “in a superb way the greatness of America’s character.” Muskie, he said, was “a man who had a strong and beneficial impact on my own life and on that of the nation.”

In Merrill Gym, the speakers’ platform was chock full of dignitaries. Maine Gov. Joseph Brennan was there, as was the entire Maine congressional delegation: representatives Olympia Snowe and John McKernan, and senators William Cohen and George Mitchell. Also on the platform was Frank Coffin ’40, who, as a federal judge, swore in Muskie as Carter’s new secretary of state in 1980. (Carter had visited Bates once before, giving a campaign speech in 1975.)

As if a visit to Bates by a former president didn’t create enough hullabaloo and hubbub, there was Hurricane Gloria. To skirt the East Coast–hugging storm, Carter first flew to Syracuse, N.Y., where the local newspaper photographed him walking through a hotel lobby in jogging shorts after a seven-mile run around Onondaga Lake.

Carter arrived on campus to the sounds of chainsaws. From early morning, Bates community members, including students, took to the campus to clear fallen limbs before the big weekend’s events, which included traditional Back to Bates festivities. Then-treasurer Bernie Carpenter wielded one of the saws and later wrote a thank-you letter to The Bates Student. “Without that extra help [from students] our campus could not have looked as great as it did on Back to Bates Weekend for our alumni and honored guests.”

During the convocation, Carter received an honorary Doctor of Laws degree, and later had a tet-a-tet with then Dean of the Faculty Carl Straub about Straub’s degree citation. The two met up, by chance, at the foot of the driveway to the President’s House as they arrived from different directions to attend a lunch hosted by Bates President Hedley Reynolds.

As Straub and Carter turned to walk up the steep driveway, Carter suddenly took the dean’s arm “and stopped my walk,” recalled Straub, who died in 2019. “He said he wanted to talk.”

Straub, who was a religion professor who would return to the Bates classroom as the college’s first Griffith Professor of Environmental Studies, had piqued Carter’s interest by invoking the environment twice in his citation for Carter.

First, he noted that “there is more than the Appalachian Trail which binds Maine to Georgia,” such as a “common heritage which rises from the simple decency of our people: We share a sense of what is good and just and beautiful.” Second, the citation praised Carter for, among other achievements as the 39th U.S. president, the “foresight to protect our natural environments, to preserve American wilderness.”

Carter, recalled Straub, wanted to talk about the Appalachian Trail. Not surprising: In 1978, Carter signed a law giving the federal government more power to protect, expand, and improve the trail.

Straub said he took a moment to thank Carter for his leadership in establishing the Denali National Park. (In 1978, Carter used executive authority to designate 56 million acres of Alaska wilderness as federally protected national monuments and in 1980 signed a law bringing the former McKinley National Park into a larger protected area named Denali National Park and Preserve.)

It was a proud if surreal moment for Straub, having a 10-minute private audience with a former president — “while dignitaries waited at the top of the driveway to welcome [Carter].”

Carter’s friendship with and admiration for Ed Muskie is well-chronicled in the public record, thanks in large part to the Muskie Archives. It shines through in the famous photo of the 5-foot-10 Carter hugging the 6-foot-4 Muskie during the archives dedication.

And it comes through in quieter ways, like the April 1981 photo showing Carter, decked out in fly-fishing gear and smiling that famous Carter grin, holding a big brown trout. On the back of the photo, which Carter sent to Muskie, he wrote, “On the opening day of the season, with my new Ed Muskie self-casting rod, I caught a lot of smaller ones, plus three over 18 inches. Thanks again. I’m sure the Maine fishing will be even better. Jimmy.”

While less well-known, the late president’s relationship with Mays was no less vital or authentic. For one, it reflected a shared Southern upbringing, wrote Damian Dominguez in a March 2023 story about the Mays–Carter friendship for the Greenwood (S.C.) Index-Journal.

“The two shared a common sensibility: Carter grew up a rural, Southern, Baptist farmer; Mays was the son of freed slaves who became sharecroppers and grew up a Baptist in rural Epworth,” Dominguez reported.

Carter and Mays probably got to know one another around 1970, Dominguez suggested. At the time, Mays, who had retired as president of Morehouse in 1967, was presiding over the Atlanta Board of Education — just as the federal courts ordered the desegregation of Georgia public schools — and Carter was ramping up his successful campaign for governor.

Mays pointed to Carter’s inaugural address as Georgia’s governor in 1971, when Carter said that “the time for racial discrimination is over.”

Within a few years, Mays, who had been advising U.S. presidents on racial issues since the 1950s, starting with Harry Truman, would announce his support of Carter for president, a decision that Mays explained during a talk at Bates in February 1977 during Black Arts Week. Then age 82, Mays spoke in the Chapel (and was introduced by Marcus Bruce ’77, then a Bates senior and now the Charles A. Dana Professor of Religious Studies).

Mays explained that he had been getting letters asking why he had supported Carter’s run for president in 1976, so he took a moment to explain his reasons. Mays pointed to Carter’s inaugural address as Georgia’s governor in 1971, when Carter said that “the time for racial discrimination is over.”

From that moment, Mays took time to “study his record, read what he said and what his mother said about Jimmy’s early years. At a time when Negroes went to the back door [of a] white house… Jimmy Carter’s black friends went in and out of of the Carter house through the front door.”

When Carter served in the Navy, Mays told his Chapel audience, his voice sounding still strong on an old cassette tape recording, “one of his friends was Black, and when he visited Jimmy Carter’s home, he was treated as a man and was a guest in the Carter home. So when he made his statement about racism in his inaugural address [as] governor, I had reasons to believe.”

Mays went on to recount the various actions Carter took as governor, including integrating the powerful Board of Regents, which controls policy for Georgia’s public university system. “He meant what he said,” Mays concluded.

After Mays’ death on March 28, 1984, Carter praised him as “my personal friend, my constructive critic, and my close adviser.”

Mays, known as the “Schoolmaster of the Movement” for mentoring Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights leaders, told the Chapel audience that in supporting Carter he was also supporting his own life’s work, to help lead the South’s emergence from its Jim Crow past. Mays spoke of growing up when “lynching was respected by the state and condoned by the church…. I knew segregation and denigration.”

After Mays’ death on March 28, 1984, Carter praised him as “my personal friend, my constructive critic, and my close adviser.” Offering one of the eulogies at his funeral, held at Morehouse, Carter described Mays as a “monumental figure in the field of education and social justice. He inspired all who knew him.”

At Mays’ funeral, when a speaker asked all the “Morehouse men” to stand, Carter stood with the many other Morehouse degree-holders — Carter had received an honorary degree from Morehouse in 1972.

“I was proud to stand as one of the Morehouse men,” Carter said in his remarks. “Dr. Mays told me that he was proud a Morehouse man was finally in the White House. He told me, ‘You may be the first, but you won’t be the last.'”