As Mara Tieken was beginning her teaching career in 2002, she pulled out a map of the U.S. Carefully considering where she, as a new elementary school teacher, would land, Tieken gazed past urban hotspots in favor of what was hidden between them. In a rural stretch of Tennessee, she found a little town named Vanleer, population 311.

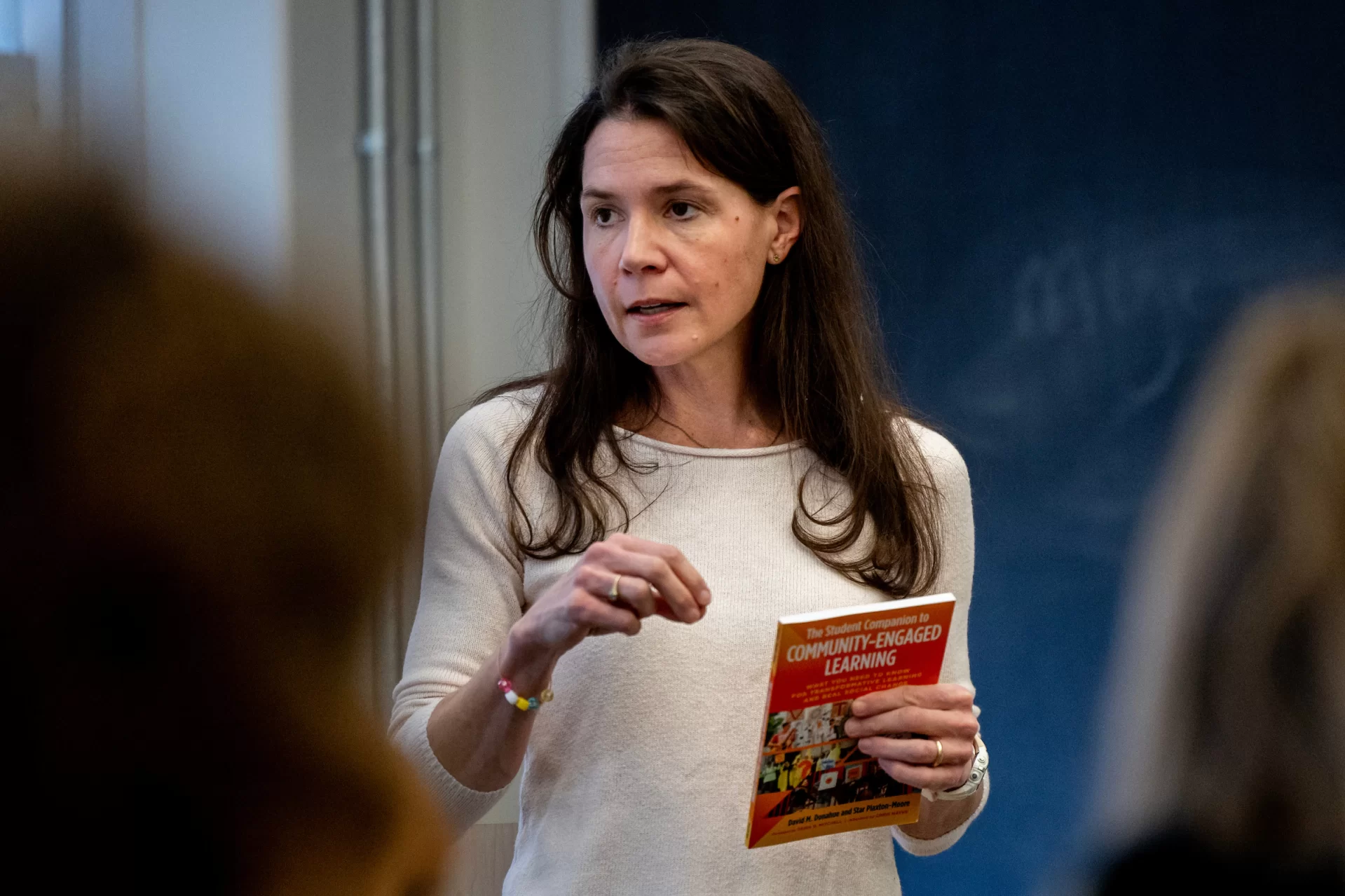

Tieken would spend the next three years as a third grade teacher in the small community. Now, as an associate professor of education at Bates, her classrooms are filled with young adults instead of 8-year-olds, but one thing hasn’t changed: how she teaches.

For her distinguished approach to education and commitment to students’ success, Tieken is the recipient of this year’s Kroepsch Award for Excellence in Teaching, the college’s highest teaching award.

Judging by what current and former students have to say, and her ongoing camaraderie with pupils from decades ago, Tieken is exceptional at what she does.

“Mara is a fantastic planner, a fierce advocate for education, [and] a compelling teacher,” says one young alumna who nominated Tieken for the award. “[She is] a mentor for those pursuing careers in education and those who are not.”

Says another recent graduate, “She always finds ways to connect coursework and subject matter to our lived experience at Bates or in our lives away from Bates.”

In her office in Pettengill Hall, a decades-old, beloved green chair that once belonged to the principal of Vanleer Elementary Schools sits across from Tieken’s desk. Like the chair, Tieken’s core teaching tenets honed during her time in Tennessee still support her work today.

For one, she prioritizes relationship-building and students’ well-being. This includes ensuring that her students are moving, eating, and sleeping enough, a practice informed by her time with third graders.

“Some of the things that we do in elementary school really work well for students of all ages, but we only do them in elementary school,” Tieken says.

In her classroom, Tieken strives to create an interactive environment. She focuses on learning through student discussion and works to build relationships among and with her students. This community feeling, she says, is key to fostering an environment where students can have respectful discussions about the often uncomfortable subjects that her courses broach.

“You’re much more likely to feel comfortable thinking differently about something if the person presenting you with a new way of thinking is someone whose opinion you respect and value,” Tieken says.

Bates’ community engagement opportunities further enhance Tieken’s dynamic classroom culture. All students taking education courses are required to complete Community-Engaged Learning (CEL) projects, which typically involve student teaching or other volunteering in the Lewiston area.

“This is really, really critical work,” Tieken says. “We’re in the middle of a teacher shortage.”

As a teacher who often teaches future teachers, Tieken will influence generations of learners. She knows that these budding educators are not only learning her course material but also watching how she presents it.

“You’ve got to practice what you preach,” Tieken says. “I think that there’s an additional level of accountability there. It’s really gratifying, though, when I see students adopting practices I’ve done in the classroom in their own classrooms.”

Malia “Mia” Taggart, an eighth grade humanities teacher at the Northwest School in Seattle, Wash., is one such student.

“I use something that Mara did in the classroom probably every day in my teaching,” Taggart says.

As a first-semester transfer student at Bates, Taggart took an education course with Tieken and was hooked. She quickly discovered that she loved teaching and built her own interdisciplinary studies major around the content of Tieken’s and other professors’ courses.

Tieken’s courses — such as “Race and Justice in American Education;” “Education, Reform, and Politics;” and “Qualitative Methods of Education Research” — often bridge sociological and educational theory. In the classroom, she presents case studies on specific schools to demonstrate the real-world implications of education policy. This method helped Taggart understand the impact of large themes in education and expand her viewpoints, growing to view teaching as a means to enact social justice.

“A lot of the learning that I did — about what oppression can look like and the complexities of that — really helped me to understand, ‘Okay, where am I?’” Taggart says. “‘How did I get here? What do I want to do to make this world a better place?’”

Tieken’s own life experiences impact how her students think. During her junior year of college, Tieken completed a teaching internship in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean. After graduating, she did a year-long post-baccalaureate fellowship at Yale before, influenced by her student teaching experiences, setting out to find a rural teaching job.

As Tieken began her new phase of life in the small Tennessee community, her school, Vanleer Elementary School, was also experiencing dramatic change under the No Child Left Behind Act, enacted in 2002. The federal law aimed to improve education nationwide through standards-based education reform, which required each state to set standards for students and measure their achievements through standardized testing.

Tieken observed the impact of the law on her small rural school. The new tests were not working for her students.

“As I was teaching, I was starting to realize how much education policy, and even guides on education practice, really didn’t have a rural context in mind,” Tieken says. “They were really created for some sort of urban or suburban context.”

After three years in Vanleer, Tieken left for graduate school to study rural education, hoping to expand academia’s understanding of how education policy affects rural schools. Her doctoral thesis at Harvard Graduate School of Education would later become her first book, Why Rural Schools Matter, which examines rural school closures and consolidations in Arkansas.

Since joining Bates in 2011 and moving to Maine, Tieken continues to research rural education systems in multiple states. She maintains a website, Rural Schools Open, that explains rural school closure and offers resources for districts facing closure. Tieken’s second book, Educated Out: How Rural Students Navigate Elite Colleges — And What It Costs Them, which tells the stories of nine rural students at an elite college Tieken calls “Hilltop,” will be released this spring.

Like the students profiled in Tieken’s book, Travis Palmer ’21 came to a small private college from a small rural town.

Palmer grew up in Rumford, Maine, in Oxford County. A once-thriving mill town, Rumford’s population has dropped by over 4,000 since 1960. About one-fifth of its approximately 6,000 residents now live below the poverty line. Like the schools highlighted in Tieken’s first book, rural schools in Oxford County have faced closure and consolidation, often heavily contested by community members.

As Tieken’s student at Bates, Palmer had the opportunity to study his own background and connect his experience as a rural student with larger educational theory.

“When we’re talking about educational reform, a lot of the time it centers around more urban areas and then spreads out to more rural areas,” Palmer says. “But Mara did a great job of connecting those two together, reemphasizing the rural, and it made me feel a lot more included on campus.”

Tieken is certainly attuned to the unique, often isolating experiences of rural students at elite, private institutions. While writing Educated Out, Tieken turned to Palmer to get his perspective on her work. He was the first person to read the book.

“It was a really great experience for me because again, it did reaffirm the things I was feeling at the time as a rural student on campus,” Palmer says. “It also gave me that agency of understanding an esteemed professor is looking for input and advice on this.”

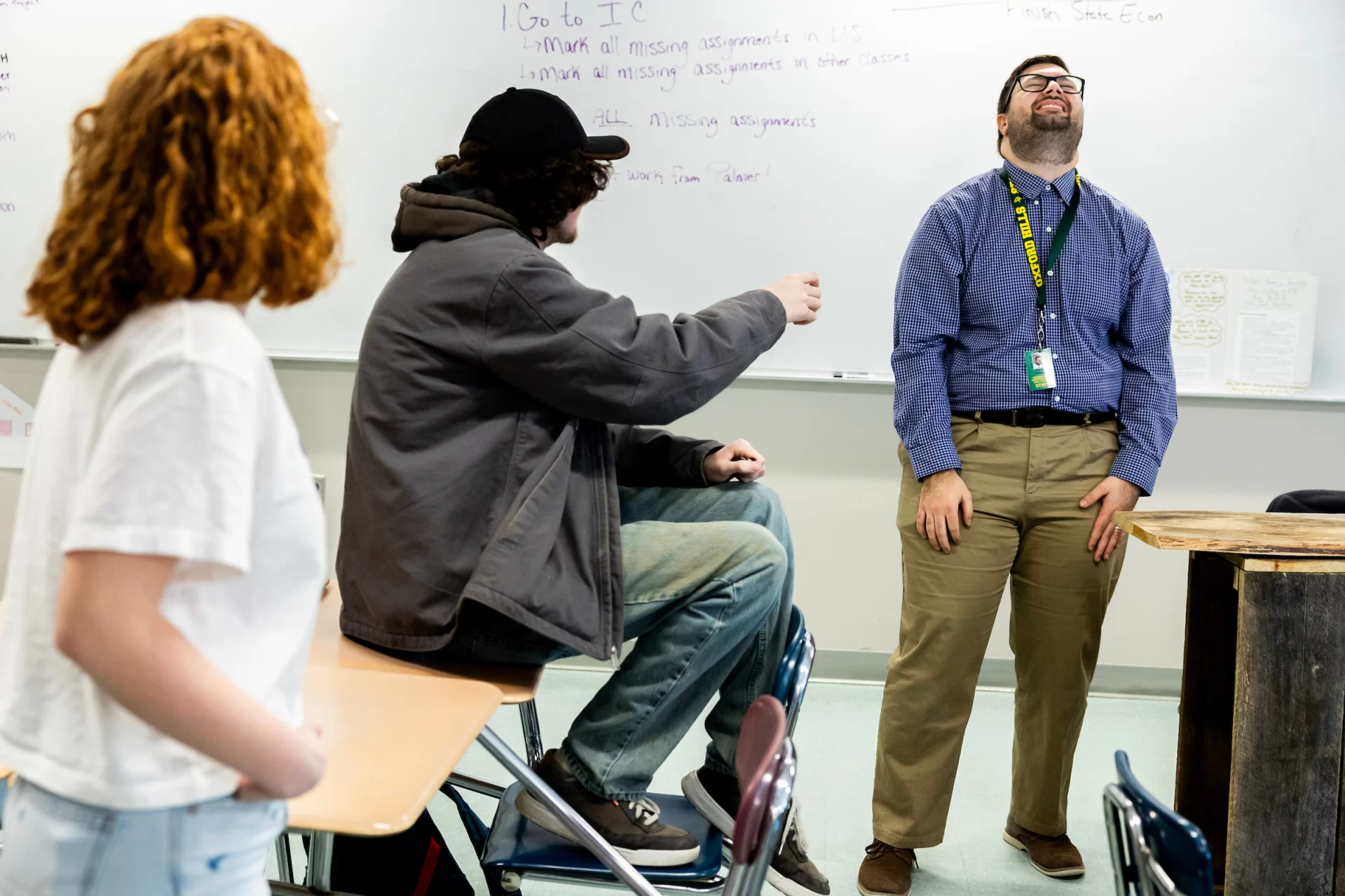

Palmer is now a social studies teacher at Oxford Hills Comprehensive High School, whose students hail from eight different rural towns, in South Paris.

“I think the best part about teaching is the relationships you develop with students, especially in the area I teach in,” Palmer says. “It’s low-income, it’s rural. There’s a lot of challenges.”

He strives to pay forward the support Tieken offered him by being a mentor for his own students, offering advice on the college application process and pointing students toward support resources.

Palmer and Tieken have remained friends and sometimes arrange playdates for their respective children, who are close in age. Palmer was not surprised to hear that Tieken was selected for the Kroepsch Award.

“The relationship we’ve developed is something special,” Palmer says. “The fact that a person can develop a relationship so closely with students is such an incredible thing.”

Through these relationships, Tieken has supported and advised countless Bates students — always reminding them that, as she gives feedback, she too is constantly working to become a better educator.

“That’s the whole thing of teaching,” Tieken says. “It’s never perfect.”

Faculty Featured

Mara C. Tieken

Associate Professor of Education