This year’s MLK Day celebration, themed “Bending Toward Justice: Peace and Nonviolence,” brought together students, faculty, staff, and community members for art and action, discussion and debate.

Here’s an in-depth, hour-by-hour look at MLK Day 2025 through photographs and words.

8:34 p.m., Sunday, Jan. 19: Speaking (and Dancing) Their Truth

The night before the full day of programming on MLK Day, the Bates community gathered in Gomes Chapel for the MLK Spoken Word Festival, where students and community guests shared themes of peace and nonviolence.

Misaki Fukushima, a Hirasawa Scholar from Tokyo, evoked the horrors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki through her performance, in which she danced to Beethoven’s sonata Pathétique and read a poem by a Japanese physician and survivor of the Nagasaki attack, Takashi Nagai.

“Although I am not from Nagasaki or Hiroshima, I grew up hearing stories of the devastation caused by atomic bombs,” says Fukashima, who hand-wrote the poem on Japanese paper and carried it in the form of an origami crane throughout her dance to symbolize peace.

“As an artist, I often feel powerless to directly impact immense issues like war and peace. However, through dance, I can empathize with the suffering of others and convey those emotions.”

The college’s historic Hirasawa Scholar program, named after Kazushige Hirasawa ’36, brings Japanese university students to campus for one year.

Seen here is Joseph Jackson, a formerly incarcerated person, reading his poetry. “If our words were songs, we’ve sung we’re hurt. We sung it in the church. We sung it to the judges, jurors, lawyers and the clerk.”

Jackson, a founder of the Maine State Prison chapter of the NAACP, now serves as co-executive director of community programs at Maine Inside Out, a Lewiston-based nonprofit that creates theater for social change in schools, prisons, and in the community.

Musician Kenya Hall’s music and words were clear and on point: “I need you to wake up! Wake up! Wake up!” — a fitting way to end Sunday evening’s MLK Spoken Word festival and propel the campus community toward Monday’s full day of programming.

9:54 a.m., Monday, Jan. 20: Media on MLK Day

After the keynote ended, President Garry W. Jenkins took a few minutes to talk to a NewsCenter Maine reporter, Alex Haskell, about the tradition of Martin Luther King Jr. Day programming at Bates, which dates back to the 1980s.

Haskell was particularly interested in the relationship between two giants of the Civil Rights Movement, Class of 1920 graduate Benjamin E. Mays and King himself, Mays having served as King’s early mentor, friend, and finally eulogizer.

NewsCenter’s coverage centered that relationship in both online and broadcast stories about the day. “Today’s message is about how we can all think about our role in social change,” Jenkins told Haskell.

The Sun Journal’s Joe Charpentier also covered the keynote, sharing highlights of Chenoweth’s research on nonviolent protest with readers.

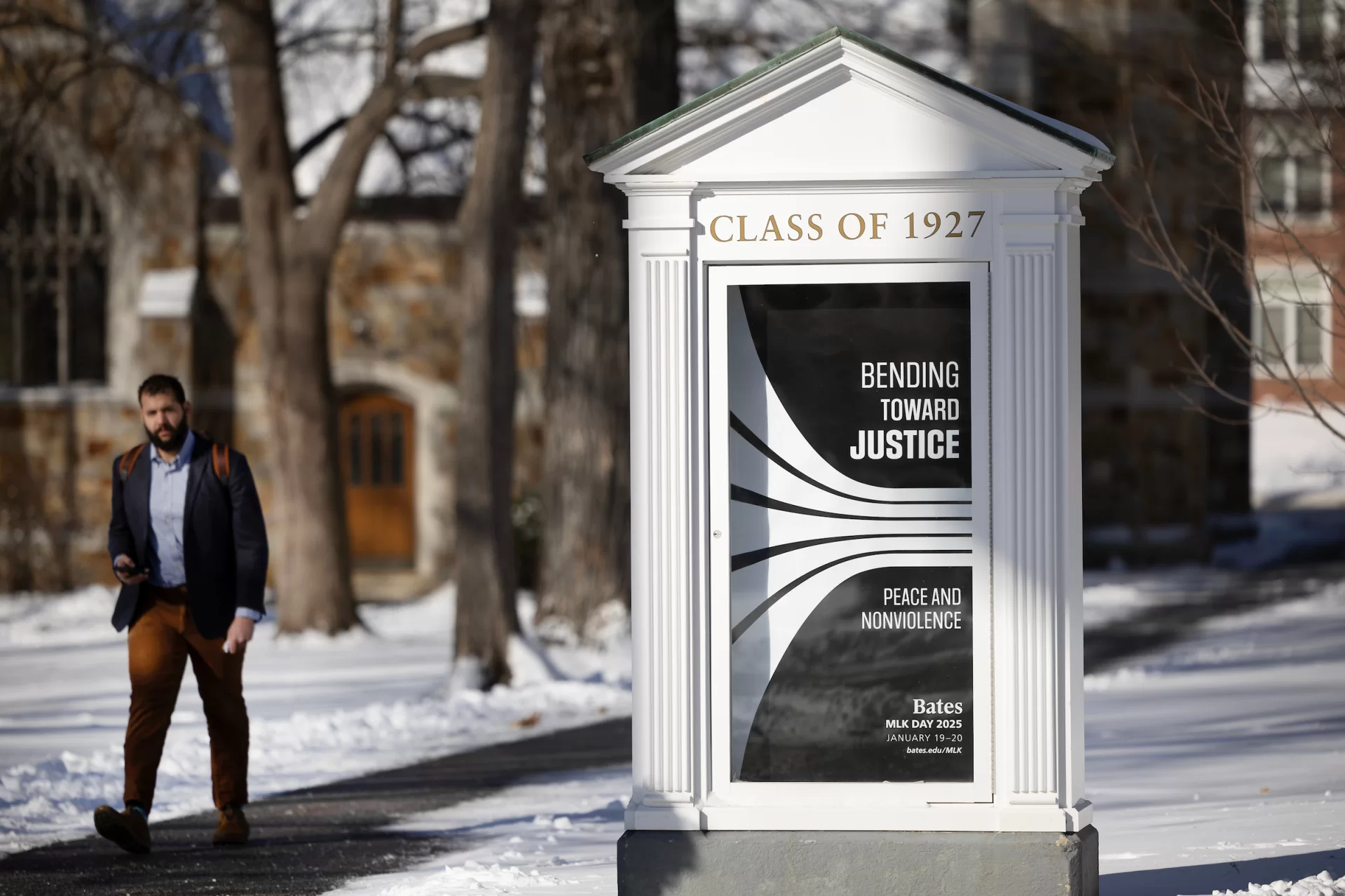

10:45 a.m. Snowy Strolling

Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Tyler Harper, who chairs the college’s Martin Luther King Jr. Day Planning Committee, walks past the Mouthpiece featuring this year’s poster for the MLK Day theme, “Bending Toward Justice: Peace and Nonviolence.”

10:48 a.m. Fashion as Subversion

Janie Phillips ’27, an English major from Portland, Ore., shared her presentation on the Black Dandy, a figure who pushes back the norms of white supremacy by “dressing to live, and living to dress.”

She walked the audience through the history of the Black Dandy, tracing its origins to the 18th century, when enslaved and freed Black individuals used fashion as a form of resistance and self-expression.

Phillips asked the workshop participants to discuss their ideas of what it means to be a gentleman, highlighting the standards of white supremacy which the Black Dandy operated within and subverted.

Drawing information primarily from the book Slaves to Fashion by Monica L. Miller, Phillips brought the audience to the present day, showing photos of modern day dandyism at the Met Gala and giving the audience a deeper appreciation for how clothing can be a form of both personal and political resistance.

11:07 a.m. Wealth as Resistance

“I just love talking about rich Black folks,” quipped Andrew Goddard ’27 as he presented the history of the Greenwood district of Tulsa, Okla., a Black neighborhood famously known for its economic prosperity in the early 1900s — and infamously known for being destroyed by a white mob over just two days of murder and mayhem in 1921.

Goddard’s presentation grew out of a project he completed last fall for the course “Black Resistance from the Civil War to Civil Rights,” taught by Frances Bell, a visiting assistant professor of history. “I thought about the concept of Black wealth,” he said. “I concluded that garnering capital in a nation where our ancestors were once viewed as capital may be the greatest form of Black resistance possible under capitalism.”

His MLK Day presentation featured YouTube video clips, archival photographs, and his own strong narrative command. For the audience, the net effect was to grasp the incredible economic and social prestige of a district that was dubbed the “Black Wall Street.”

“They had up to 600 businesses in the district. I know that number is huge — just absurd — in a 35-block radius. Unreal,” he said. “Forty grocery stores, 30 restaurants, at least 15 physicians, some of which were regarded as some of the most talented in the country. And six private airplanes, which at the time was kind of just a weird flex!”

A mob destroyed the district and killed upward of 300 people from May 31 to June 1, 1921. There are two known survivors of the massacre, Viola Fletcher and Lessie Benningfield Randle, both over 100 years old, but legal efforts to seek justice for them and descendants of those killed have not been successful.

As Goddard said in his talk, his focus was not on the massacre, but on what existed and what it meant: “possibility, advancement, but even fear that arises as a result of widespread Black wealth, social capital, and unity.”

Reflecting on what he learned from the project, Goddard said that he “really wanted to figure out what this place looked like, how it came to be, and the reasons behind why things are the way they are.

“I guess it just told me that I like finding the truth.”

11:09 a.m. Biopic Depictions

Simply being oneself can be a powerful action, explained Charles Nero, Benjamin E. Mays ’20 Distinguished Prof of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies, in his presentation “Sexy Peace.”

The talk centered around Bayard Rustin, an anti-violence pioneer and one of Martin Luther King Jr.’s closest but oft-overlooked mentors. As a Black, gay man in the 1960s, Rustin was often an outsider among his fellow activists and in greater American society.

Nero used the 2023 biopic Rustin, based on Rustin’s life and starring Colman Domingo, to exhibit how Rustin’s sexuality and his fight for civil liberties were inextricably linked.

“There’s a tremendous amount of resistance to Bayard Rustin as a Black, gay man who is not private about his sexuality, who does not conform to respectability politics,” Nero said. “He’s making the activists very nervous.”

As the film’s characters prepare for the historic 1963 March on Washington, Rustin’s fellow civil rights leaders worry about how the public will respond to him being openly gay. Rustin asserts that he cannot and will not change how he presents his sexual orientation to the world.

“What you see, I cannot conceal,” Rustin says.

11:21 a.m. Community on Track

Bates students and local children came together for a morning of games, crafts, and mentoring, embodying the spirit of service and inspiration central to MLK Day.

11:56 a.m. Community from the Ground Up

Minquansis Sapiel, Passamaquoddy Tribe member from Sipayik, led a morning workshop, “Honoring Water and Land,” which centered the wisdom and resilience of the Passamaquoddy Indigenous people in Maine.

Sapiel spoke about her experiences of isolation and frustration growing up Native in Maine and then opened up discussion groups on taking actions to support and grow community.

“Let’s decolonize our minds a little bit,” Sapiel told the packed house in one of the conference rooms in Commons. “That means assess our values from the heart.”

But first, something had to be done about the furniture. “ I feel like institutions like this…,” she said, gesturing to the lines of chairs set up, audience style, and shaking her head. “This whole setup, I would not have it this way. I would not have us lined up and just me out there alone. I would have us in circles engaging, because like I said in the beginning, it takes all of us and all of our minds.

“Each and every one of us have something to bring to the table. When we learn that and know that, we can create the most powerful, wonderful things. So I would love that for us.”

Once students, faculty, and staff had settled into groups, Sapiel gave them a single, action-oriented question to consider: “How are you going to show up for your community?”

Kyle Woodworth ’25, of Berwick, Nova Scotia, got right to business as facilitator for his group. “I think talking about what we can actively do for our communities is a good question,” Woodworth said. “I think before we begin we probably want to think about what community means to each of us. That’s a very different thing.” And the group was off and running.

1:59 p.m. Grief and Poetry, Personal and Universal

Cal Dagner ’27 of Crozet, Va., read her poetry aloud during the workshop “Where Does Your Grief Sit?” by Portland’s poet laureate Maya Williams.

Williams asked the workshop participants to describe physical aspects of grief prompted by the poems, societal expectations about grief they’d witnessed, and the power of art in the face of loss. Attendees offered poems from different areas of history and parts of the world, all united by the theme of grief.

From rhyming poems by the ancient Greek Simonides to meditations on suicide by Iranian-American poet Kaveh Akbar, Williams guided participants through a journey of understanding grief as both a deeply personal and universally human experience.

3:03 p.m. Malleable Memory

Jenna Dela Cruz Vendil ’06, associate director of democratic engagement and student activism at the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, welcomed attendees to the workshop “Reclaiming Public Memory.”

The session addressed grassroots work in Maine from scholars, artists, and culture keepers that are shaping public conversations. These efforts offer new possibilities for changing relationships that have political impacts on Wabanaki and African American communities.

3:32 p.m. Different Kind of Justice

Bates Restorative Practices student advisors Risa Horiuchi ’25, John Campana ’26 (center), and Julia Parham ’25 led “Building Bridges for Healing” workshop participants in restorative justice exercises.

An alternative to retributive justice, restorative justice aims to mediate conflict, remedy harm to victims, and discourage future harmful behaviors through community-building practices.

Facilitators began with an introductory activity intended to make the room into a “sanctuary,” where participants felt comfortable sharing and exploring new ways of communication. In the next activity, attendees paired up to have conversations about conflict focused on active listening and responding.

“It’s sometimes hard to do active listening because often we are trying to think of what we want to say,” Parham said. “I invite you to challenge that.”

Student advisor Nice Matrakul ’26, Assistant Dean of Community Standards and Deputy Title IX Coordinator Andee Bucciarelli, and Andrew Forsthoefel, the restorative practice systems specialist with the Cumberland County Public Health Department, also facilitated the workshop.

Forsthoefel first learned about restorative justice while completing a year-long walk across the North American continent with a sign reading “Walking to listen” taped to his back.

In the Western U.S., members of the Navajo nation introduced Forsthoefel to restorative justice, which has roots in indigenous culture. He went on to complete an eight-year apprenticeship with a Navajo restorative justice master practitioner.

“We have to remember that this isn’t something new we’re making up,” Forsthoefel said. “We’re inheriting an ancient wisdom that is finding its way into modern society.”

4:23 p.m. Spreading the MLK Love

Emmy Comrack ’25 of Washington, D.C., prints a Bates MLK Day ’25 design on a tote bag during a screen printing workshop in Olin Arts Center. At right is Michel Droge, a visiting lecturer in art and visual culture.

Several student-created designs were available for printing, including one displayed by Sarah Van Lonkhuyzen ‘27 of Rockport, Maine, who was one of the first students to ink up a themed screen print.

4:49 p.m. Debating Justice

The annual debate in the Olin Arts Center Concert Hall honoring the Rev. Benjamin E. Mays, welcomed students from Morehouse and Bates colleges.

Mays, a 1920 Bates graduate, was a longtime Morehouse College president known as the “Schoolmaster of the Movement” for mentoring Martin Luther King Jr. and other future civil rights leaders.

This year’s topic was “Resolved: Law and order exists for the purpose of establishing justice.” It drew from Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” in which King decried the inaction of the country’s faint-hearted “white moderates” who professed allegiance to the civil rights movement yet seemed to prefer inaction to action.

King wrote, “I had hoped that the white moderate would understand that law and order exist for the purpose of establishing justice and that when they fail in this purpose, they become the dangerously structured dams that block the flow of social progress.”

7:56 p.m. Ending Together

In the evening, the Olin Arts Center Concert Hall was the setting for the final event of the college’s MLK Day observance, a montage of student presentations addressing the day’s theme as well as the legacy and aims of social justice. Here, Sebenele Lukhele ’26, a biological chemistry major from Manzini, Eswatini, speaks to the gathering.

Reporting by Jay Burns, Alexandra DeMarco, Mary Pols, Hannah Kothari ’26, and Ramona McNish ’28 of Bates Communications and Marketing.

Faculty Featured

Charles I. Nero

Benjamin E. Mays '20 Distinguished Prof of Rhetoric, Film, and Screen Studies

Joyce N. Bennett

Associate Professor of Anthropology