Looking out at the audience gathered in Gomes Chapel on Monday morning, Erica Chenoweth, an expert on nonviolent protest and this year’s Martin Luther King Jr. keynote speaker, piqued the audience’s interest by saying they could easily mount a big, DIY nonviolent protest that very evening.

“Let’s say we all got on social media and said we are organizing a mass demonstration tonight in, say, Portland, and we said, ‘Be there or be square,’ and we had a couple of fun little slogans. I kid you not: We could get 10,000 people to do it, just like that.”

Yet the ease of creating such a protest, said Chenoweth, is partly why nonviolent movements around the world are achieving less success than ever: Organizers are embracing easy tactics instead of doing the hard work that marked the successes championed by King and his mentor, the Rev. Dr. Benjamin Mays, Bates Class of 1920.

At Bates, MLK Day can be retrospective, as in 1999, when the writer John Edgar Wideman gave a heartbreaking address, “Looking for Emmett Till,” about the infamous and haunting black-and-white photograph of Till, a boy who was lynched in Mississippi in 1955, lying in his casket.

Other times, MLK Day at Bates responds to the “fierce urgency of now,” as King said, such as in 1991, when the Bates faculty voted to cancel classes and hold a day of discussion about the war in Iraq, which had broken out five days earlier.

That pivotal moment in Bates’ MLK Day history was highlighted by Bates Student Government co-president Dhruv Chandra ’25 of Kolkata, India, who, with co-president Ethan Chan ’25 of Westborough, Mass., offered a welcome that framed this year’s keynote as a “now” moment.

“Today we find ourselves navigating similar complexities in a world still fraught with conflict, war, and social injustice,” Chandra said. “The values Dr. King championed — peace, nonviolence, and justice — are more relevant than ever.”

With a presidential inauguration occurring nearly simultaneously in Washington, D.C., the 2025 MLK Day keynote was here and now. Speaking from the Gomes pulpit, President Garry W. Jenkins addressed the elephant in the room in his opening remarks.

“We all know how contentious the recent presidential election cycle was. We all remember Jan. 6, 2021. We know that such transitions can be disorderly and even violent. We all, whatever our leanings, understand that these are uncertain times, to be sure. There’s ample anxiety about what’s to come [and] potential changes that may be faced in this context.”

Jenkins invoked the words of Benjamin Mays, Class of 1920, who delivered the final eulogy for Martin Luther King Jr. at Morehouse College on April 9, 1968. Mays said that King “gave people an ethical and moral way to engage in activities designed to perfect social change without bloodshed and violence.”

And as the U.S. confronts potentially divisive new policies under a new administration, Jenkins encouraged Bates to embrace Mays’ and King’s ideas, modeling civil discourse while honoring diverse perspectives.

In light of potential policy shifts that could challenge higher education, Jenkins reaffirmed Bates’ responsibility to learning and civic responsibility. “We will defend to the fullest of our abilities the importance and power of higher education. This may not always be easy work, but it is essential work. It is what Dr. King and Dr. Mays call upon us to do.”

Chenoweth was introduced by Assistant Professor of Environmental Studies Tyler Harper, who chairs the college’s Martin Luther King Jr. Planning Committee.

Harper linked Chenoweth’s work on the promise of nonviolent action to H.G. Wells, who, shortly before his death in 1946, predicted “that humanity could not be trusted with nuclear power, that were the atom bomb ever invented, full-scale nuclear war would be inevitable in the near term.”

Yet, “nearly eight decades have passed since nuclear weapons were invented, and they have never again been used in combat,” said Harper. “The worst did not come to pass. Humanity proved more capable of restraint than imagined.”

That restrain, that possibility, of “peace and specifically peace through justice and nonviolence, our keynote speaker Erica Chenoweth has devoted their life to studying.”

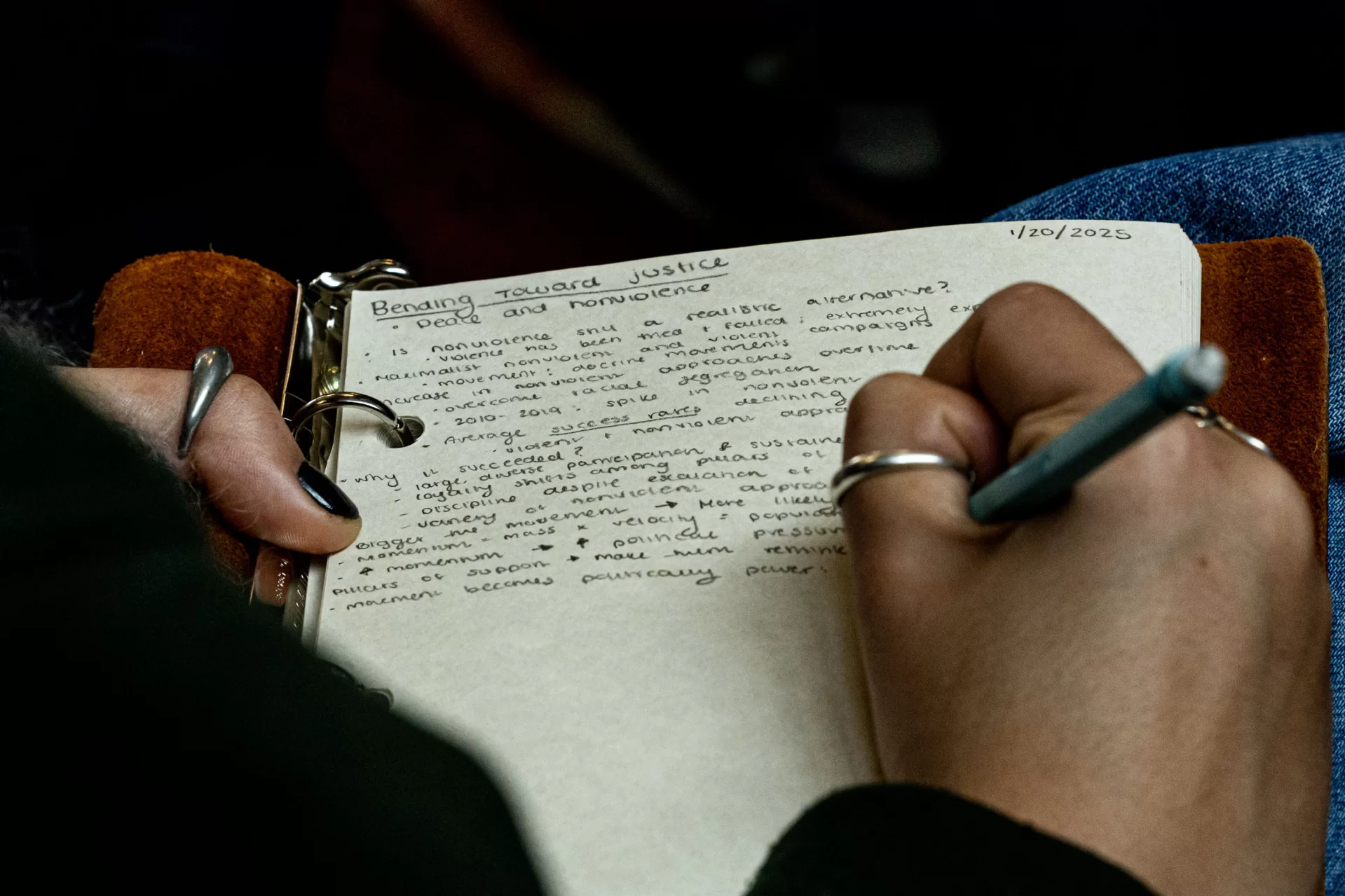

In their keynote, Chenoweth, who is a professor at Harvard University, shared findings from their book project, The End of People Power. Chenoweth’s other books include 2011’s Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, with Maria Stephan.

Beginning with Mahatma Gandhi and his followers, who successfully kicked the British out of India, and on to the U.S. Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, nonviolent protest has had a good run by relying on training, strategy, discipline, and organization.

“Basically, we’ve lived through what you might call ‘Gandhi’s century,’” said Chenoweth, noting that Gandhi began articulating and experimenting with methods of organized, collective, nonviolent action in the 1920s, which would spread around the world, including to the U.S., thanks to Martin Luther King, in service of desegregation and dismantling Jim Crow.

Since the early 1900s, nonviolent movements have succeeded more than twice as often as the violent ones, Chenoweth said. “On the face of it, [that] gives a lot of credit to King’s argument that there is a realistic alternative to violence, even for revolutionary goals.”

They succeeded through large, inclusive participation, strategic planning, and disciplined resistance. And they use diverse tactics. “They don’t just stick to a single technique like protest or marches.”

But in the last decade, even as the tactics of nonviolent protest have been embraced in historically large numbers (think of those images of mass protests in Myanmar or Belarus), “we have seen a historic decline in their effectiveness,” said Chenoweth. “We are now basically to pre-Gandhi levels of the success of unarmed collective action.”

(Chenoweth defines success of a “maximalist” campaign as ousting an authoritarian leader or achieving a revolutionary goal within a year, and recent research indicates that the findings are likely also to apply more narrowly, to protests over policy issues.)

So, organizers, listen up about why protest success is slumping:

Authoritarian regimes are learning and adapting

Autocrats have learned from the successes of past nonviolent movements and developed strategies to counter them. “Many different dictators no longer take for granted that they can just ignore these movements or expect to politically survive in the face of them,” Chenoweth said.

Autocrats use tactics like narrative control, delegating violence to unidentifiable actors, selective repression, and counter-mobilization. And they share the playbook with other autocratic regimes.

“It’s a very well-worn toolkit,” said Chenoweth, that “blames a movement on outsiders or foreigners, mischaracterizing people who engage in nonviolent resistance as terrorists or coup plotters or traitors.”

Decline in “defections”

To succeed, a movement needs defections from key pillars of society, like security forces, which are crucial for the success of movements.

For example, mass protests led to the toppling of Slobodan Milošević in October 2000. Importantly, those large protests undermined the loyalty of Milošević’s police force. Interviewed afterward about why they didn’t follow one order to shoot live fire on the demonstrators to disperse them, the police said things like, “I thought I saw my kid in the crowd,” or “I thought I saw wife’s brother,” or “I thought I saw the guy who sells me liquor on Saturdays.”

In other words, Chenoweth said, “a very large and diverse participation [in protests] activates all kinds of loyalty questions that can prove politically very powerful.”

But today’s regimes “have figured out how to proof themselves against consequential defections in ways that movements haven’t fully grappled with.” What movements might do, said Chenoweth, is be more strategic. Do homework. Get some intel. Find out which of the pillars, “whether they’re business elites or state media or security forces, are already a little shaky in their loyalty, and go for them first, and that activates the cascade of defections.”

Over-reliance on mass demonstrations

As noted earlier, movements today are choosing to pick the “low-hanging fruit” of the nonviolence orchard, neglecting deeper preparation or strategy, or another tactic altogether that might not be photo-friendly.

“If we are in an Instagram world, what could be cooler than a reflection of 2 million people on the streets in Rio de Janeiro?” Yet tactics like a stay-at-home action might be just as effective, “but people don’t know what they’re looking at when they look at a photo of an empty marketplace in Kashmir. I’m sure that it took them longer to prepare for and to execute the stay-at-home demonstration and a general strike than it does for us to whip up a mass demonstration.”

Today’s movements “might be missing out on some of the real political power that can be built and developed by basically training, preparing, thinking about a strategy of impacting those pillars and then organizing tactics to match the strategy.”

Lack of training and preparation

Movements today often lack the organizational foundations and training in nonviolent resistance seen in past successful movements.

“Maybe movements today haven’t had the deep civil society organizational basis and the preparation that movements like the civil rights movement and the noncooperation movement in India spent years developing before they ever mobilized.”

Smaller average participation

Movements today tend to mobilize smaller proportions of the population compared to earlier successful movements.

“Movements in the 1990s and the 1980s [had] some of the biggest movements…. 3 to 5 percent of the population participated in these mass movements. Now we’re more down to the average campaign getting about 1 percent.”

During the audience Q&A, a student said that he was struck by a scene in Fantastic Mr. Fox, when the minor character Petey adopts a revolutionary tone yet remains loyal to the farmers, helping them dig out the foxes. “That’s a little bit what I feel like sometimes when I’m rallying against the machine [yet] do all these things that support all the institutions in power.”

When you feel complicit in something or otherwise struggling to go along, you have three choices, Chenoweth said, referencing Albert Hirschman’s book Exit, Voice, and Loyalty. “One is exit, which is just get out of there and go do what you want to do. The second is voice, which is protest, and the third is loyalty, which is basically just acquiescing and going along.”

Each person must make their own choice, each person must “examine your values, where your heart is, and your future aspirations. Be real with yourself. Write down what you’re trying to achieve in the world and how you are going to behave and not behave in order to live your values.”

With the help of friends, advisers, and mentors, Chenoweth wrote their own personal ethical code, as a way to live their values.

While Chenoweth wasn’t trying to be directive, “there are reference points for the values that we might align to. And those are things like the Universal Declaration of Human Rights or the Declaration of Independence and the incredible aspirations defined in it, which inspired even the civil rights movement in making the claim that all people are equal in the eyes of God.”

Ultimately, Chenoweth noted, “I spent a lot of time working with and for people who are involved in the very movements that I study. They inspire me and give me a lot of hope.”

Faculty Featured