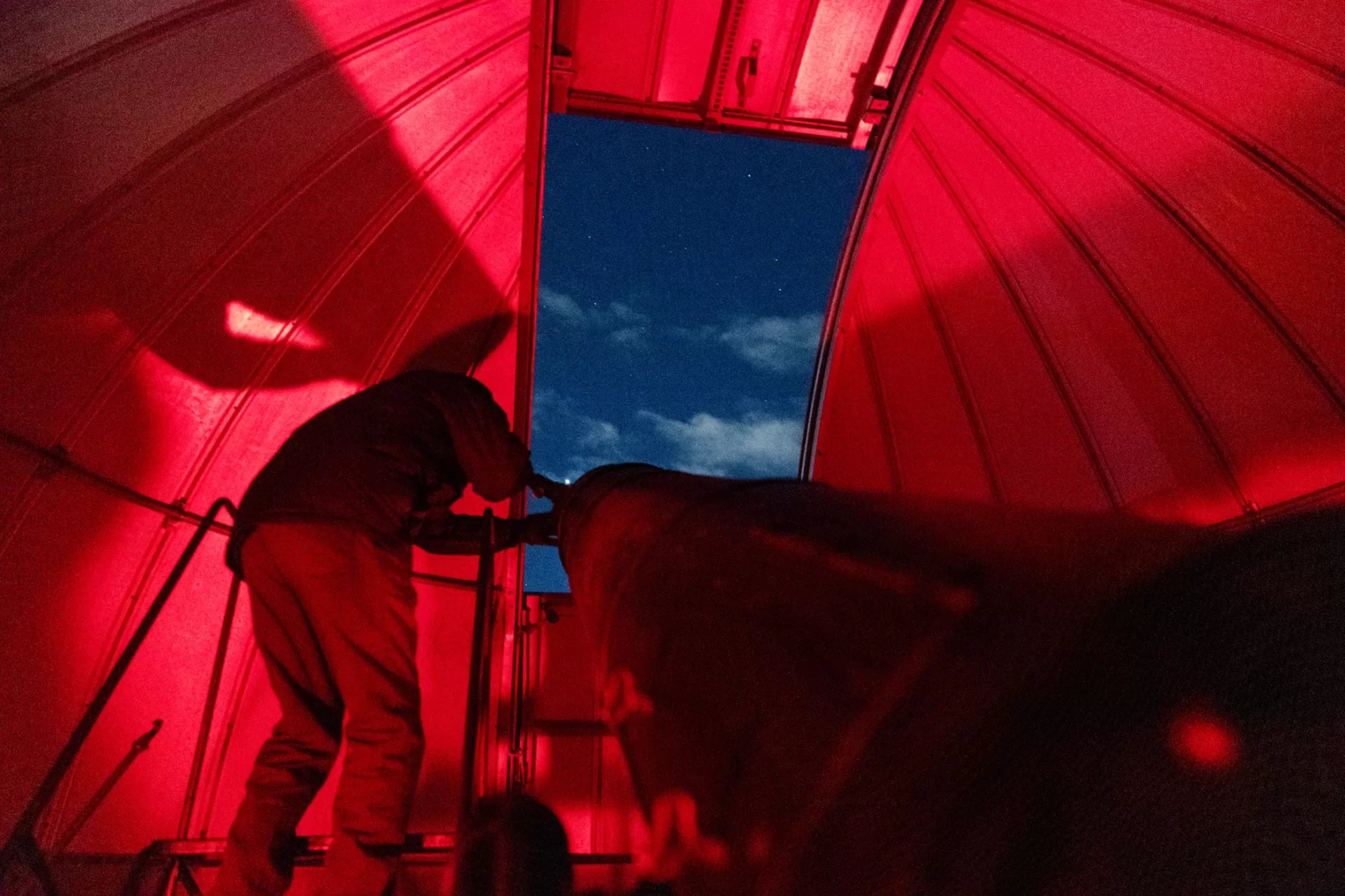

When you first brave the January cold and walk up to the roof of Carnegie Science Hall to visit the college observatory, it feels sort of like being in a boat. Varnished wood planking, large slow-moving machinery you need to push around, and the strange feeling that the world outside your container is slowly moving around you.

The observatory houses the Stephens Telescope, given to Bates in 1949 by a self-taught astronomer, Roscoe G. Stephens of Kennebunk, who built the Newtonian reflector telescope himself.

The observatory is a hidden gem on campus, one that the Bates Astronomy Club is determined to share with the student body. “It’s such a great place,” said club co-president Evan Boxer-Cook ’26 of Scarborough, Maine. “I love bringing people up there for the first time. Seeing their reaction to the telescope is incredibly rewarding.”

Tonight, Boxer-Cook is guiding a group of about a dozen students to the observatory to see a close grouping of Venus, Jupiter, Mars, and the waning gibbous moon. The club usually hosts a monthly full moon viewing, but last week’s full moon viewing was thwarted by clouds, so they decided to have another session focused on the many visible planets.

It’s no surprise that many of the visitors are first-year students. The club, revitalized in recent years by co-president Jade Pinto ’25, a double major in physics and Asian studies from the Bronx, New York, places an emphasis on inclusion.

“One of our missions is to spread the idea that the sky is open to everyone. You don’t have to be a physics major to be involved,” says Boxer-Cook, who is a classical and medieval studies major.

Much like Roscoe Stephens himself, who was a photographer, machinist, mason, and chicken farmer in addition to his astronomy interests, Boxer-Cook’s interests are wide and varied.

In high school, he earned awards in English, Latin, and physics; at Bates, he tutors students in Latin, serves as an officer of the Classics Club, and has worked in the Muskie Archives and Special Collection Library.

As ancient disciplines, classics and astronomy intersect in myriad ways, and one way becomes apparent when Boxer-Cook talks about hobbies, which include the history of timekeeping and navigation instruments such as astrolabes. During the visit to the observatory, he shows me one astrolabe, which looks like a palm-sized sundial, but with a lot more detail.

“The astrolabe is a two-dimensional representation of the celestial sphere,” Boxer-Cook explains. “It can model the movements of the sun, stars, and planets. Basically, when you rotate this, you can get a snapshot of your local sky at any moment in time, and you can solve all kinds of astronomical problems with that. It’s had many, many centuries of continued use.”

The technology we use on this night holds some similarity. Before we head up to the observatory, we gather in the physics department’s seminar room, where Boxer-Cook projects an image from the website Stellarium Web onto a screen, which displays the position of celestial objects in the sky above Bates at this exact moment. We use what we see as a reference to show us where to point the Stephens Telescope as we look for Venus, Saturn, and Jupiter.

Inside the observatory, students climb a ladder one by one to look through the eyepiece to view each planet and inform each other of their positions. Boxer-Cook adjusts the telescope by hand to track celestial objects as the Earth rotates.

The telescope’s tube measures 8 feet, 8 inches. Though hand-made by a self-taught astronomer, the instrument has long been considered a marvel of engineering, particularly its 12.5-inch mirror, which took Stephens six months to grind by hand.

Though some adjustments are made by hand, electric motors control other parts of the observatory’s operation. One motor opens the dome’s shutter to the night sky. Another operates a rack and pinion gear system that rotates the entire dome.

And another small motor, not in use tonight, drives a worm gear that moves the telescope to track planets. Its design was aided by a senior thesis in physics by Jen Brine ’00, “Motorizing the Telescope in the Carnegie Science Observatory.”

As I take my turn peering through the eyepiece, it is strange to watch the planets crawl across the lens, feeling very fast and very slow at the same time. “They look like photos in a textbook,” says Celia Horowitz ’28 of Salt Lake City, Utah.

Toward the end of the night, after everyone has had a chance to look at every planet, Boxer-Cook encourages us to come back to the observatory, either during other club events or on our own as certified telescope operators at Bates.

Handling the certification process is Cole Hastings, a physics and astronomy assistant in instruction who oversees the observatory and the Ladd Planetarium.

“Not many people know that anyone can be certified,” says Boxer-Cook. “You don’t have to be in the club. They tell you that in astronomy classes, but it’s a very underutilized resource on campus, and we’re happy to be spreading the word.”