Q&A: Based on a Short Term to Saudi Arabia, Loring Danforth’s new book challenges ‘destructive’ Orientalism

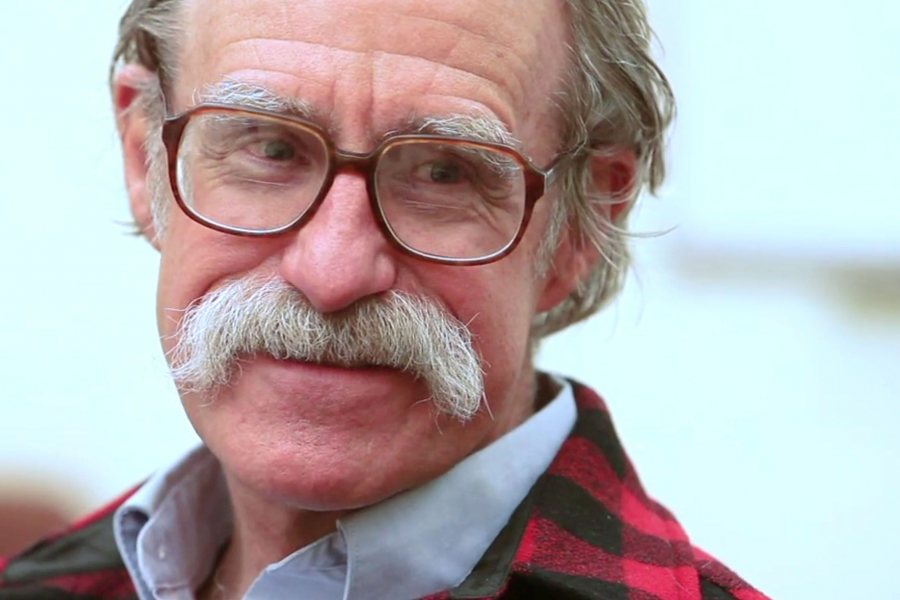

A member of the Bates faculty since 1978, Dana Professor of Anthropology Loring Danforth has published Crossing the Kingdom: Portraits of Saudi Arabia, based on the Short Term he led to that country in 2012. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Five years ago, a Bates student made Dana Professor of Anthropology Loring Danforth an offer he couldn’t refuse: Would he be interested in leading a Short Term course to Saudi Arabia?

“I was stunned,” recalls Danforth.

Few people get to visit Saudi Arabia, let alone study there. For one, the country does not issue tourist visas, the Lonely Planet calling it “one of the most difficult places on Earth to visit.”

Crossing the Kingdom: Portraits of Saudi Arabia challenges “destructive Orientalist stereotypes of Saudi Arabia,” says Dana Professor of Anthropology Loring Danforth.

Meanwhile, the U.S. State Department routinely warns visitors of the “ongoing security threat due to the continued presence of terrorist groups.”

Against that backdrop, the Bates trip to Saudi Arabia that Danforth and his 16 students took in the spring of 2012 enjoyed amazing access facilitated by the student who made the offer to Danforth, Leena Nasser ’12, a politics major from Dhahran, whose father works for a multinational corporation in Saudi Arabia.

The Bates group got to visit with academic and religious leaders; journalists, artists, and human rights activists; and top-level executives with the national oil company, Saudi Aramco.

A few weeks after the trip, the school year was over, and Danforth was poised to embark on a sabbatical-year research project in Greece, a country whose culture and history had yielded four scholarly books over Danforth’s career.

But as he tried to start his intended project — studying a transborder national park in northern Greece — he felt a professional calling to “prove worthy” of the “priceless gift” of the experience in Saudi Arabia.

So he wrote a book, Crossing the Kingdom: Portraits of Saudi Arabia (University of California Press, 2016), a collection of essays on Saudi topics with chapter titles such as “Roads of Arabia: Archaeology in Service to the Kingdom,” “Driving While Female: Protesting the Ban on Women Driving,” and “Saudi Modern: Art on the Edge.”

(In fact, Danforth is using his experience with Saudi modern art to co-curate, with director Dan Mills, the exhibition Phantom Punch, opening at the Bates Museum of Art in October.)

Here’s what Danforth said about a book whose major goal is to challenge “destructive Orientalist stereotypes of Saudi Arabia by offering alternative images of its people, their society, and their culture.”

Who should read this book?

Everybody who is interested in Islam. Everybody who is interested in the Near East. Everybody who is interested in Saudi Arabia and the Arabian Peninsula.

As you put off the Greek project to write this book, who was your sounding board?

Nobody. We had just gotten back from Saudi Arabia. There was graduation, and I’d moved over to Frye Street, where my office would be for my sabbatical. I’m thinking, “Okay, now I can start working” on the Greek project. But the Saudi stuff was just so fresh and interesting.

I didn’t fully understand it. I couldn’t process it. And I felt it was so valuable and interesting that I couldn’t let it go. So I figured, “Okay I’ll try to write a New Yorker-style article. I started one and finished it. Then wrote another. Then I thought, “Maybe I have a book.”

This is not a traditional academic monograph. When I spoke to a publisher about it, I said, “It’s a good thing I didn’t need this book to get tenure.” And he said, “If you’d needed this book to get tenure you wouldn’t have written it.” Which is unfortunately true, in a way.

There’s a line in your introduction that says, “As an anthropologist, I felt an obligation to prove worthy of this opportunity.” Why the qualifier “as an anthropologist?”

The experience was so quintessentially anthropological: where you go to another culture and you’re talking to people and learning about their culture.

One of the reviewers said, basically, “You think you can visit Saudi Arabia for a month and write a book?” But that’s what a writer like Jane Kramer of The New Yorker does. She once visited Greece for a week, wrote an article for The New Yorker, and it was very good. She got it.

The issue is not how much time you spend in a country. It’s the quality of what you have to say.

What was it like being a teacher, a Bates representative, and a researcher all in a single trip?

I was most aware of juggling all those roles when we walked into an government office, say the Ministry of Education, and it was my job to hand out some Bates gear and say, “Here we are from Bates, and it’s a pleasure to be here.”

The students were watching me, and I was modeling diplomacy. But I wanted to give them the opportunity to ask questions. And I had questions myself.

I am a better teacher because I am a scholar. But the reverse is not always true.

It was just an unbelievable experience, shifting from spending an hour talking with students in the evening about what we learned, then going back to my room and scribbling notes myself.

I would try to get them to take notes at the level at which I did. They’d ask, “Do we have to write all the time?” And I’d say, “Yes, you have to write all the time.”

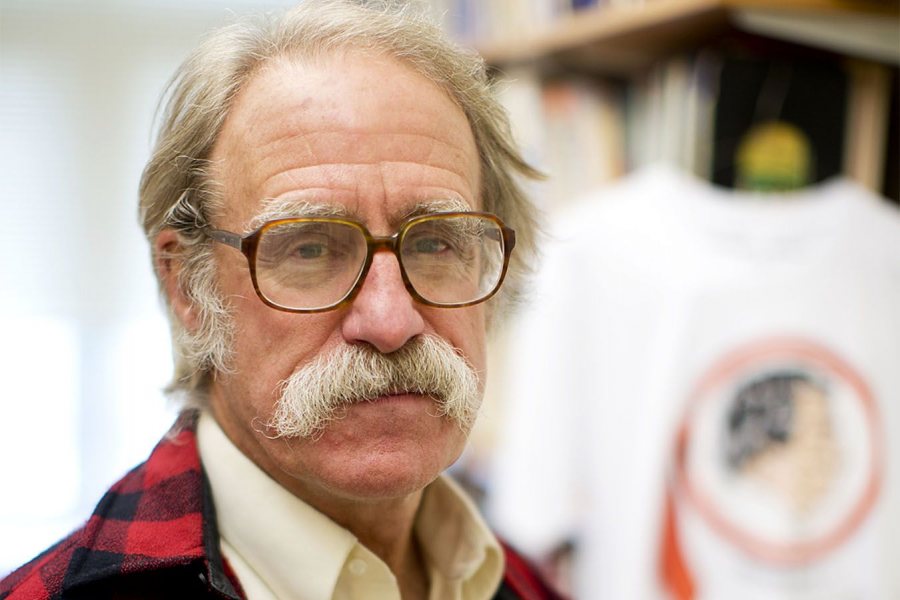

“For 40 years I’ve been totally committed to the balance of teaching and scholarship that exists at Bates,” says Dana Professor of Anthropology Loring Danforth. Still, he says, there’s a tension between the two. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

We say that teaching and research are in balance at Bates. But in terms of your experience in Saudi Arabia, were they integrated?

For 40 years I’ve been totally committed to the balance of teaching and scholarship that exists at Bates. But often at an individual level, hour by hour and week by week, there’s a tension between the two.

I am a better teacher because I am a scholar. But the reverse is not always true. I can’t take Bates students to Greece — my research is just not set up to have students next to me as I’m trying to establish rapport with an elderly Greek woman.

But the Saudi Arabia trip was a total synthesis of the two, where I was there with 16 students teaching a course, and that experience was also giving me a chance to do fieldwork.

You said your skills as an ethnographer and writer allow you to share new insights in the Saudi culture. What are the skills?

Part of doing fieldwork — interviewing people and observing things — is just raw commitment. Everything that happens and everything people say, you just write it down as carefully and as fully and as accurately as you can.

Another really important part of it is an eye for detail. In a hotel, I saw a laundry slip that had the most amazing list of the kinds of clothing worn by the people who stayed there — from 1950s American styles to South Asian clothes to Arab clothes, and I just said to myself, “The whole world is in this list.”

It’s the ability to notice things that are revealing and interesting.

You quote anthropologist Clifford Geertz, who said that good interpretive anthropology means making “small facts speak to large issues.” Isn’t there a chance that a broad judgment extrapolated from small facts can be quite wrong?

Yes. An Orientalist could take a concrete fact, that 15 of the 19 terrorists on 9/11 were from Saudi Arabia, and go off and say it’s an evil country. Being concrete doesn’t necessarily lead to avoiding negative generalizations.

During the 2012 Short Term to Saudi Arabia, anthropology major Devin Tatro ’14 talks with Saudi men during an outing to a desert farm in the Eastern Province. At the gathering, the Bates women got permission not to wear their abayas. (Photograph by Ana Bisaillon ’12)

Whatever issue you are trying to speak to, you can find examples that support it and you can find examples that don’t support it. Either way, you need the ability to maintain that the complexity of the world throughout your interpretation.

Geertz uses the phrase “thick description” to describe this kind of interpretive anthropology. For example, you might ask, “What’s the point of Hamlet?” Well, it has lots of points, and to make sense of it as a whole means I have to show you the complexity, depth, and meaning of the text.

That’s true whether it’s the text of Hamlet or a Greek ritual. The situation at hand is always more complex than people think. And often that’s what good anthropology ends up arguing.

How did your group park their Western perspectives when looking at Saudi Arabia?

Well, our group wasn’t all Western. We had students from Lithuania, Nepal, China, as well as Saudi Arabia itself.

We were in a hotel and some Chinese businessmen arrived. I said to the Chinese student, “Why don’t you talk to them?” She said, “In China, you can’t just go up and start talking to people.” I said, “We’re not in China. Go talk to them.”

But it’s totally accurate that we have assumptions that come from our own cultural background, and we have to bracket those, put those aside, and then decide whether they’re relevant.

We had an encounter with a Saudi woman who argued that homosexuality is evil. Sodom and Gomorrah being buried in lava showed that God punished homosexuality.

My feeling is that if you aren’t going to talk to people that you disagree with, then you might just as well stay home.

Our students — one with two mothers and another whose uncle is gay and had just adopted a child with his partner — were just shaking listening to this stuff. In that situation, do you say, “Oh, homophobia. Gee, how interesting”? Or do you say, “I disagree with that”?

The students expressed their disagreement politely and respectfully. One was in tears afterwards, fearing she’d insulted the woman. I said, “No, you spoke up and expressed your opinion.”

My feeling is that if you aren’t going to talk to people that you disagree with, then you might just as well stay home. But it’s a challenge to navigate this path, when to be relativistic and when to say, “This is not how I would want my country run.”

You describe how you feel when you experience a new culture, calling it almost like a secular conversion experience. Is it what the Greek philosophers might’ve called enthusiasmos?

Enthusiasmos: “God in you.” Like spirit possession. Yes. It’s a motivator. You have this overwhelmingly powerful experience — what are you going to do with it? You can’t just forget about it or let it pass or ignore it. You want to do something worthwhile with it or share it.

In a note to your students at the end of the course, you said the experience in Saudi Arabia might prove to be “ineffable” — inexpressible.

I told them that they do not have to be able to share the experience. A transcendent, ineffable experience can enrich your life. I told them to hold on to it as long as they can.

During the 2012 Short Term to Saudi Arabia, a group of Saudi boys cavort for the camera during a desert outing to the Eastern Province. (Photograph by Gintare Balseviciute ’13)

It’s really hard to share such an experience with somebody who wasn’t there. People are going to say, “How was Saudi Arabia?” And you’re going to want to talk for an hour, and they’re going to say, “So what happened at the faculty meeting yesterday?”

But from a teaching perspective, you do want your students to be able to communicate what they experienced, right?

Yes, and there are good ways to do it. Theses, presentations, and talking to your friends are all ways to try to keep it alive. You just have to work hard to find people who have a genuine interest.

Bates does a good job at giving students a serious chance to communicate their abroad experiences, whether formally through thesis and coursework or informally through continued get-togethers between faculty and students. Until the students on the trip all graduated, we had dinner once a month, if only so they could say, “Wow, remember when we did that?”

We talk about purposeful work at Bates. An anthropological experience like this can inspire you to commit yourself long-term to helping people understand Islam or helping people understand the Near East or working for peace in the Near East. And several students on the trip have done so.

How does the book reflect what it was like watching your students experience Saudi Arabia?

That was a struggle because I didn’t want it to be a book about “Our Trip to Saudi Arabia,” or “this is what it’s like to travel with a group of students to Saudi Arabia.” I had no desire to write that kind of book.

But the last chapter, “Who Can Go to Mecca?” has a section about a dilemma that arose during the trip.

We had met Dr. Sami Angawi, an inspiring religious leader. I think of him as a Muslim Quaker or a Muslim Unitarian Universalist, a concept I didn’t think could exist, but I was wrong. He told me that he’d be happy to arrange for me to visit Mecca. I said that I wasn’t a Muslim. He said, “That’s between you and God. If you’d like to go to Mecca, I can arrange it.” I said, “Thank you but I don’t think that would be appropriate.”

But some of the students saw him the next day. Afterward they told me that they were going to go to Mecca.

I said, “But you’re not Muslim.” They said, “That doesn’t matter.” I said, “Oh, yes, it does,” and they said that Dr. Angawi was going to arrange it.

It turned out that they were planning to go to the Islamic Education Foundation in Jeddah and sign a statement that would make it possible for them to go to Mecca. I asked about the statement, which, it turned out, was the Shahada, the Muslim declaration of faith: “There is no God but God, and Muhammad is his messenger.”

I had individual meetings with two of the three and said, “Are you really going to convert to Islam?”

So I said, “You’re going to convert to Islam?” No, they told me. “We’re just going to say that and then go to Mecca. I said, “Well, you are going to convert to Islam. Do you really want to convert to Islam?”

I asked our hosts, and I asked people at Bates: “What should I do?” I was responsible for their safety. I didn’t feel I could just say to them, “You can’t convert to Islam.” But I wanted them to know that was what they were doing. So I had individual meetings with two of the three and said, “Are you really going to convert to Islam?” The details are in the book, but it was really uncomfortable and painful and awkward, and they were angry at me.

Ultimately, I didn’t say, “You can’t go.” I said, “If you do this you’re converting to Islam, at least as I understand it.” And I said that if they went to Mecca and missed the plane — this was the last day of the trip — they were on their own. In the end, for a combination of reasons, they didn’t go.

To me that was really interesting. I was taking a harder line than Dr. Angawi’s more inclusive approach. I was defending the Saudi government’s position that only Muslims can go to Mecca, which is a position I don’t agree with individually.

When you challenged the students, were you challenging them as their teacher, as a researcher, as the leader of a Bates contingent in country?

Not as a researcher, no. It was as a teacher in the broadest sense, and as a Bates official in a narrower sense. I didn’t want an article in The New York Times about some Bates students arrested for going to Mecca.

What I was more focused on, and what I was taking really seriously, was what the right thing to do was morally. And I had a firm belief that from my perspective it was morally wrong for them to go to Mecca.

As a teacher, are you teaching morals?

I was teaching the issues that came out of that dilemma, which were directly related to the question of what it means to convert.

As a teacher and Bates official, I decided that it was not my position to forbid them from converting to Islam. But I wanted them to know that in my opinion they were really converting to Islam. They needed to think seriously about it, and if they wanted to read and study the Qur’an for a couple years, then convert, and then go to Mecca, that made perfect sense.

But if they want to go to Mecca now because they think they might maybe think about becoming a Muslim — it just struck me as irresponsible.