Mara Tieken, an ‘exceedingly important voice’ in rural education, receives national award

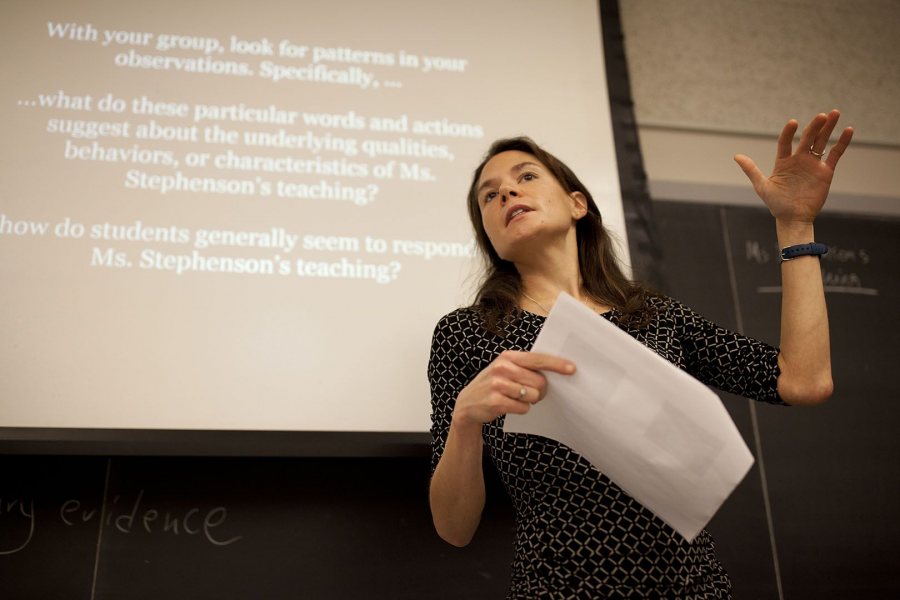

Assistant Professor of Education Mara Tieken, shown leading her “Perspectives on Education” class in 2014, has won a national award honoring early-career professors who practice community engagement as they teach, research, and serve. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

Like the third-grade teacher she once was, Assistant Professor of Education Mara Tieken communicates in simple terms.

That’s especially — and perhaps surprisingly — true when it comes to her academic work, a burgeoning body of research on rural schools and related topics that is bridging the traditional divide between academics and practitioners.

For that accomplishment, Tieken recently won the Ernest A. Lynton Award for the Scholarship of Engagement for Early Career Faculty, a national award honoring professors who practice community engagement as they teach, research, and serve.

The award shines a light on the “two commitments that characterize Mara’s life and work,” says Darby Ray, a faculty colleague of Tieken’s. As director of the Harward Center for Community Partnerships, Ray nominated Tieken for the Lynton Award.

The first is a “commitment to social justice in a diverse democracy,” Ray says. “The second is ‘reciprocal partnership’ — that is, she includes community partner voices and desires at every stage of her work.”

What Tieken does today also pays homage to her first job after graduating from Dartmouth in 2001 with a social psychology major and education minor: teaching in Vanleer, Tenn., population 398, for three years.

“I did worry that I was giving up,” Tieken says of her decision to leave elementary school teaching in 2005. (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

While the work in Vanleer was rewarding, she says, teachers and staff “felt overlooked and misunderstood by researchers who never wrote about rural schools, who misunderstood their experiences and were oblivious to the distinctive character, challenges, and strengths of rural education.”

When rural schools weren’t being ignored, she says, they were treated as something that needs fixing, and the fixes tended to be “ill-fitting, urban-centric education policies that endanger schools and, therefore, communities.”

So Tieken left Vanleer to do something about it.

“I did worry that I was giving up,” she says of her decision to leave for the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 2005. “But I wanted to do something about that gaping hole” — the lack of books and research that might speak to the challenges of her rural classroom and rural schools.

Tieken’s book, Why Rural Schools Matter was published in 2014 by the University of North Carolina Press.

Tieken earned a doctorate in education in 2011 and, in 2014, published her book, Why Rural Schools Matter, which shows the harm of those ill-fitting policies, like school consolidation, which states undertake as a response to declining enrollments and the pressure to cut spending.

That tactic sounds sensible, she says, but consolidation can inflict huge costs on rural communities.

In the case of Delight, Ark., for example, school consolidation reversed the long-standing reality of desegregation as families self-selected new schools along racial lines. “A desegregated district vanished, the lines of race redrawn,” wrote Tieken.

Appointed to the Bates faculty in 2011, Tieken came to the right state to continue her and her students’ examination of both rural and urban schools.

“My courses focus on fieldwork,” she says, and in the last five years, the 500 students in her courses have contributed more than 15,000 hours of tutoring, mentoring, teaching, researching, and organizing to Maine’s second-largest urban area.

In one recent example, Tieken and students in her qualitative methods course (a course that she created) partnered with two Lewiston nonprofits that support teen parents, Goodwill Take Two and Advocates for Children.

Helping the nonprofits do what is often hard — find the time to measure and catalog their successes and challenges — the students developed methods, collected data, and presented findings that “were used by the organizations in grant applications and for strengthening programming,” Tieken says.

And while one in five children in the U.S. lives in a rural area, in Maine that figure is closer to one in two. That means the stakes are high when it comes to rural education in Maine, as Tieken found when she researched her most recent article, “College Talk and the Rural Economy,” published in the Peabody Journal of Education in May.

Visiting rural Maine towns to learn about college aspirations, Tieken interviewed and observed various stakeholders including high school guidance counselors, visiting college admissions officials, and the staffs of community-based organizations.

Tieken found that students hear one message over and over: A college education means a job. Yet there’s a downside when communities frame higher education that narrowly, says Tieken. A jobs-focused mantra can “exclude other benefits” of a college degree, such as higher life satisfaction or the social benefits of an educated citizenry.

Further, “the ubiquity of the [jobs] message may cause students to be pressured into too-early career choices that leave them with few options later in life as industries change.”

“College Talk” is a good example of Tieken’s plainspoken and distinctive approach to her scholarship. Known as “portraiture,” it’s a method of social-science inquiry using close observation, engagement, and partnership to tell a story.

Indeed, “College Talk” begins the way few scholarly articles do, putting the reader right into a rural community on the day of a college fair at the local high school:

By the end of October, the trees edging town already stand as bare as telephone poles. Leaves lie in long, windswept drifts along the road, and soon there will be snow. But, for now, it is still fall: a season of football games played under bright stadium lights, pumpkins growing orange and fat on thick brown stalks, and weekends filled with deer hunting and bonfires.

Tieken learned portraiture late in her graduate work at Harvard; up to that point, she worried that she was becoming the kind of academic her former self would have abhored: someone trained to gain access, collect data, and maintain objectivity — “utilitarian practices that seem to make research a contextless, possibly exploitive process.”

Portraiture gave Tieken a qualitative and “ethically comfortable method to do the work I’d left teaching to do.” (Phyllis Graber Jensen/Bates College)

With portraiture, however, the “standard of rigor is authenticity.” That opens the door for the researcher to “focus on particulars; it is in the details that greater truths reside.” Instead of distance, portraiture “relies upon reciprocal, balanced relationships shared by researcher and participants — genuine relationships based on respect and honesty.”

In the end, portraiture gave Tieken a qualitative and “ethically comfortable method to do the work I’d left teaching to do.”

Ray says that Tieken’s jargon-free approach means that her scholarship has greater value (because it’s comprehensible) outside academe; to that end, Tieken shares her results in “diverse venues and styles” in order to “suit partner needs and to influence public opinion and policy.”

Those venues have ranged from academic journals to recent public radio interviews in Maine and in North Carolina to community suppers.

All of which makes Tieken’s voice “exceedingly important,” Ray says, not only in the “academy and in the halls of government and policy development, but also in the diners, school gymnasiums, community centers, and classrooms of rural America.”