Bates makes art history this week, and it all started five years ago when a student stopped by anthropologist Loring Danforth’s office and proposed that he create a Short Term course in her native Saudi Arabia.

Danforth was all for it. But he was a little surprised when Leena Nasser ’12, a politics major from Dhahran, suggested that the itinerary include Saudi art galleries. His own anthropological research hadn’t involved art. “I was initially unclear why those were on her schedule,” says Danforth, Charles A. Dana Professor of Anthropology.

Clarity came quickly once Danforth had seen contemporary work by Saudi artists during that 2012 Short Term visit. “Seeing this stuff was amazing,” he says. “It offered really interesting insights into Saudi politics and culture.

“I fell in love with it” — to the extent that Danforth approached Dan Mills, director of the Bates College Museum of Art, about the possibility of mounting an exhibition by Saudi artists at the college. Mills, in turn, proved eager to co-curate such a show with Danforth.

From “Elementary 240,” 12 photographic prints and a video by Njoud Alanbari. (Courtesy of the artist)

The museum opens the exhibition, Phantom Punch: Contemporary Art from Saudi Arabia in Lewiston, on Friday, Oct. 28. And it makes Bates one of the very few U.S. art museums, and the first in New England, to offer a major show of work by contemporary Saudi artists.

A central goal of Phantom Punch “is to promote cross-cultural understanding between the U.S. and the Arab Islamic world,” says Danforth, who wrote a chapter about his encounter with contemporary Saudi art in his book about the trip, Crossing the Kingdom: Portraits of Saudi Arabia (University of California Press, 2016).

“We want to show that there are creative, interesting, critical people who are exploring the political and cultural issues in their society. And we want to undermine the notion that Saudi Arabia is an evil place of oppressive kings, and that there’s nothing there but oil and sand.”

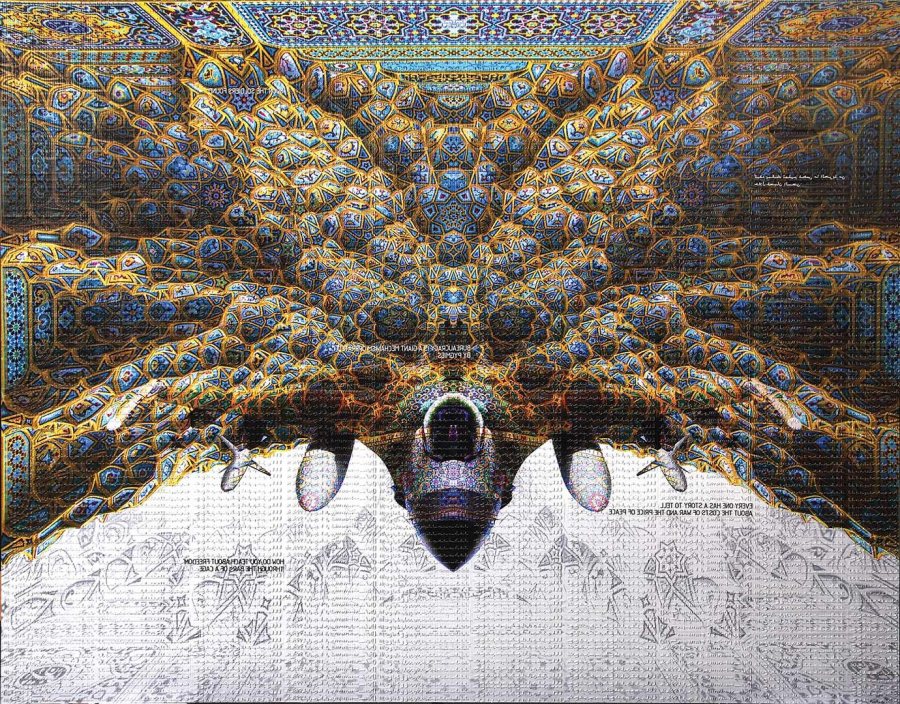

“Ricochet” (2015), a work in rubber stamps and industrial lacquer paint on plywood. (Private collection, Switzerland)

One of four related exhibitions that have popped up across the nation this year, Phantom Punch presents work by leading and emerging Saudi artists in diverse media, from calligraphy to comedy, from painting to photography to video.

Fifteen individual artists and two video collectives address issues exigent in Saudi society and its relationships with the world — the role of women, the impact of the oil industry, the interaction between American pop culture and traditional Saudi values, and the limits of censorship and intolerance on freedom of expression, to name just a few.

A brief clip from the 2014 video “Never Never Land” by Arwa Al Neami is on view in Phantom Punch at the Museum of Art.

Friday’s opening includes a 6:30 p.m. lecture by Ahmed Mater, one of Saudi Arabia’s best-known artists and one of six participating artists to attend the opening. The exhibition includes the U.S. debut of Mater’s video Leaves Fall in All Seasons, a look at how the holy city of Mecca is being transformed into an environment that favors the super-wealthy to the detriment of less affluent people.

Related programming on campus and in the broader community takes place in the days immediately following the opening, and again in February. The other Phantom Punch artists visiting Bates into next week are Nouf Alhimiary, Musaed Al Hulis, Arwa Al Neami, Rashed Al Shashai, and Ahmad Angawi.

If the year’s politics have brought U.S. nativism and anti-Muslim attitudes to the fore, Danforth and Mills feel that this wracked political atmosphere is an ideal backdrop for an exhibition that, says Mills, “confronts and confounds either preconceived notions or, perhaps, little knowledge about other parts of the world.”

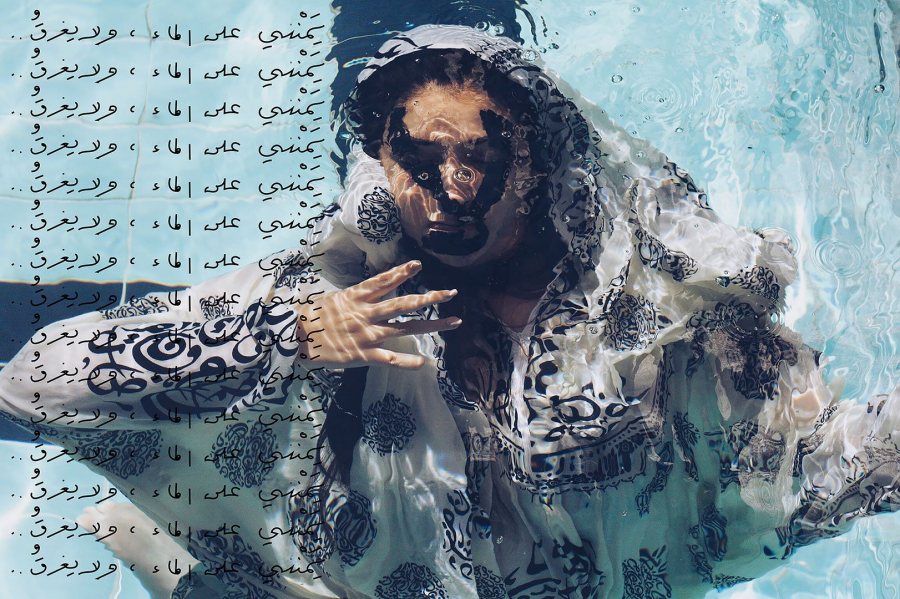

An untitled photograph from “The Desire Not to Exist” series by Nouf Alhimiary, 2015. (Courtesy of the artist)

While one political camp is saying, “Let’s not let Muslims in the country,” Danforth adds, “we’re not only bringing over people from Saudi Arabia, but we’re bringing in their art and trying to show it to as many people as we can — all of which is in direct opposition to that kind of Islamophobia.”

The Phantom Punch artists, he adds, offer a world of “Saudi commentary on larger issues that American media comment on — only they do it through art and from an insider’s perspective. They’re raising issues that we all need to think about.”

The Bates show is distinctive in several ways. It’s the first group show of Saudi artists at a U.S. academic institution, and the first where the presenting institution led the curatorial work. In addition, Mills and Danforth have significantly expanded the number of artists receiving U.S. exposure, including women — nearly half of the Phantom Punch artists are women.

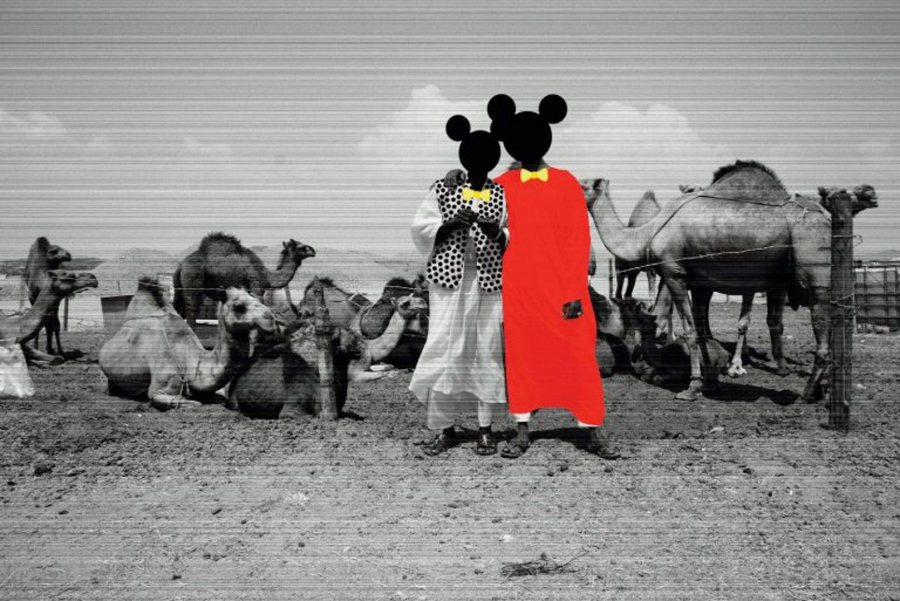

This digital print from the series “Tagged and Documented” (2013) by Huda Beydoun appears in the Bates exhibition Phantom Punch.

Fans of boxing history and American pop culture will recognize the term “phantom punch.” Though unseen by many in the audience, that was the blow that gave boxer Muhammad Ali the World Heavyweight Championship victory over Sonny Liston, after just a couple of minutes in the ring, in Lewiston in 1965.

What does that notorious knockout have to do with an exhibition of art from Saudi Arabia at Bates College? It applies on a few different levels. For one thing, as Danforth explains, Cassius Clay’s conversion to Islam, which occasioned his name change to Muhammad Ali, carries powerful symbolism.

“He was initially despised for being against the Vietnam War and for converting to Islam,” Danforth explains. Yet Ali went on to become a figure beloved by mainstream Americans. “So he’s a figure who embodied negative attitudes and then positive attitudes toward Islam.”

In addition, Mills explains, the very existence of Phantom Punch — a show of art made by residents of a country where censorship is pervasive and strictly enforced — comes as a surprise.

“Most people, when they think of Saudi Arabia, aren’t thinking of smart, savvy, technically amazing contemporary art,” Mills says. “So it’s like, ‘What, avant-garde Saudi art?’ It’s a cultural phantom punch — you didn’t see it coming.”

As they commenced assembling the show, Mills and Danforth reached out to Stephen Stapleton, a British artist active in supporting Saudi artists since the early 2000s. The Bates team’s timing was auspicious: As Phantom Punch was taking shape, Stapleton was part of a group organizing the three other U.S. exhibitions of Saudi art this year, in Aspen, Colo., San Francisco, and Houston. (Meanwhile, the Smithsonian’s Arthur M. Sackler Gallery this year organized Mater’s first U.S. solo exhibition.)

Although Mills and Danforth curated Phantom Punch, the exhibition received valuable logistical help from Stapleton and a U.S. organization with which he’s affiliated: the artists collective Culturunners, which mounted the western U.S. shows and whose modus operandi includes awareness-raising road trips in a converted RV. (Mills took part in a Culturunners trip in the Gulfstream RV for a five-day, 1,100-mile tour between the Saudi exhibitions in Aspen and San Francisco last summer.)

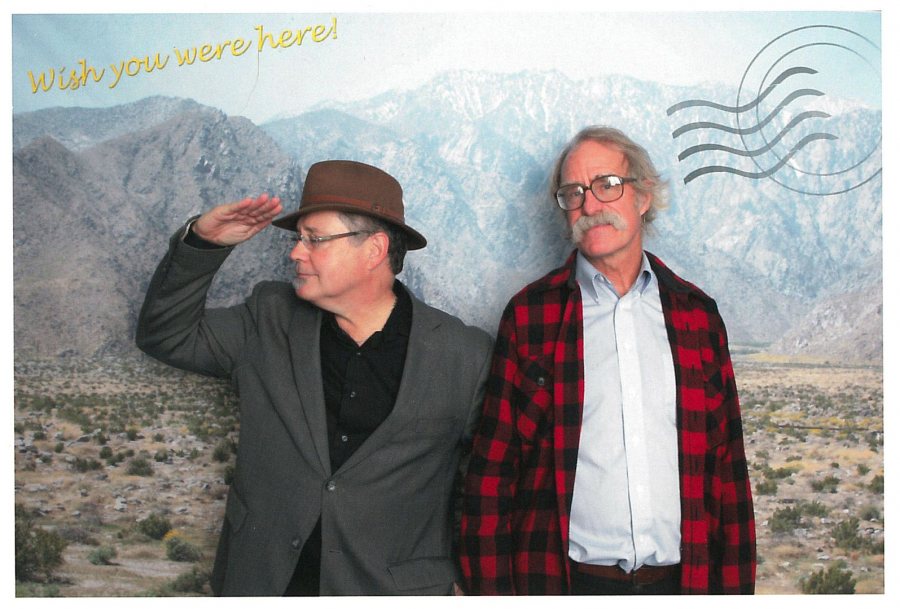

Bates College Museum of Art Director Dan Mills, left, and Charles Dana Professor of Anthropology Loring Danforth.

“Their intention was essentially to use contemporary Saudi art as a platform for dialogue and communication with the West,” says Mills. “And we responded to that.”

All four shows have been supported by the King Abdulaziz Center for World Culture in Saudi Arabia. Also partnering with Bates for Phantom Punch are Mater’s Pharan Studio and Gharem Studio, whose principal, Abdulnasser Gharem, is another leading light in the Saudi art world.