This story appeared in the Fall 1996 issue of Bates Magazine.

Entering the 1946 college football season, Bates was fielding a team that hadn’t played in three years due to World War II. The wartime hiatus was perhaps a blessing, considering the team had posted just one winning season and one Maine state title since 1930.

The 1946 Bates home opener was played even before students returned to campus from summer break, and the next two games were on the road. The entire roster was made up of just 28 players (the 1996 team, in comparison, has 68) in an era when starters played both offense and defense, so every injury was a double loss.

But despite not having played a formal game for so long, the team was confident. “Most of the guys were veterans of the war. We had no doubt we would do well,” said Linden Blanchard ’49, then a sophomore guard on the team.

Flanked by cheerleaders, Ohio Gov. Frank Lausche (left) accepts an 18-pound lobster from Bates athletic director Monte Moore, Class of 1915, on behalf of Maine Gov. Horace Hildreth at halftime of the Glass Bowl between Bates and the University of Toledo on Dec. 7, 1946. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

“Except for the freshmen, most of the players out there were men, not boys,” said Dean Emeritus of Admissions Milt Lindholm ’35, who had admitted most of the players on the team.

With World War II servicemen returning to college nationwide under the G.I. Bill, it was not unusual for postwar athletic teams to feature older players. On the 1946 Bates team, for example, most of the seniors were between 24 and 26, and all the players but two had served in the war.

“They were married and had experienced a lot in the war,” Lindholm said. “We were aware of the talent from [the last prewar team], but that season was exciting.”

Allen Howlett ’49 picks up rushing yardage in Bates’ 6-0 win over Bowdoin on rainy, muddy Garcelon Field before 3,000 on Back to Bates weekend on Nov. 2, 1946. (Muskie Archives and Special Collections Library)

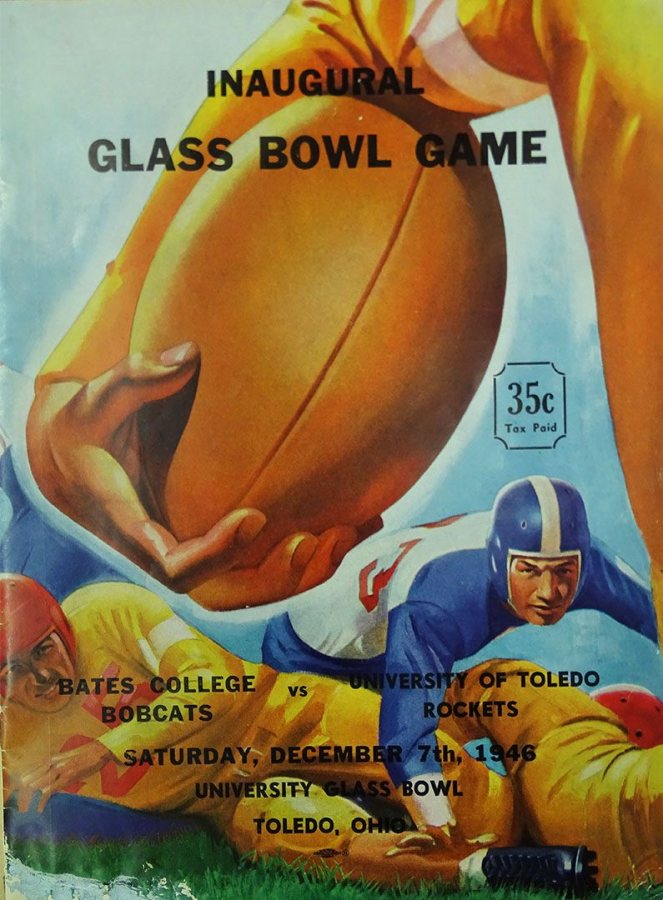

From uncertain beginnings, the 1946 team turned in the most successful season in Bates football history, finishing the regular season at 7-0 and outscoring opponents by a combined score of 89-10. As one of the few unbeaten and untied teams in the nation, Bates was extended the first postseason invitation in Maine history, to the inaugural Glass Bowl versus the University of Toledo Rockets of Ohio.

“It was a great group of guys,” said Linden’s younger brother, Art ’50, who in 1946 was a 24-year-old freshman who played an integral role as the season moved on. “We gave 100 percent the whole way.” The Bobcats established a powerful defense early in the season, shutting out Massachusetts State College, 6-0, and Trinity, 26-0, in their first two games.

Though Bates was often at a size and weight disadvantage, Bates head coach Raymond “Ducky” Pond made key personnel moves throughout the year — such as putting the freshman Art Blanchard into the lineup when senior star back Arnie Card went down — to get the most out of his team.

Several New England newspapers of the day selected him as Coach of the Year, an honor usually reserved for larger colleges, and he finished ninth in the Associated Press national voting. “He really inspired confidence in us,” Art Blanchard said. “He wasn’t a ‘rah rah’ type of coach. He just always knew the right thing to say.”

One of the significant moments of the season was a 7-4 win over Maine in the team’s fifth game of the season. While 50 years later such a game would be seen as an obvious mismatch (Maine plays a Division I-AA schedule today), the Bobcats were more evenly matched with Maine in 1946.

“The difference was not as big then as it is now, but it was still there,” Art Blanchard said. “But we were confident.” However, when a bad snap on a Bates punt attempt gave Maine a safety and the lead, and then star running back Arnie Card left the game with a broken leg, the Bobcats seemed headed for their first defeat.

But the passing game, which had put up 39 points in the previous two games (a 19-6 win over Tufts and a 20-0 defeat of Northeastern) and the defense took control. Midway through the fourth quarter, Bates recovered a Black Bear fumble inside the 20 yard line and took the ball in six plays later. “The veterans we had equaled the game out,” said Linden Blanchard.

The offense slowed down in the last two games, a pair of rain-soaked 6-0 wins over Bowdoin and Colby. “The weather for those games was terrible, but we managed to pull them out in the end,” said Art Blanchard.

After the undefeated regular season, Bates was abuzz with anticipation: Would Bates become the first team from Maine to go to a bowl game? The inaugural Glass Bowl, hosted by the University of Toledo, seemed a good bet.

The Bates athletic department was confident of a bid. Athletic Director Monte Moore sent a message to Toledo stating that Bates would “come if invited.” Two weeks prior to the game, at a luncheon in Ohio and via a press release in Maine, the bowl’s organizing committee made the announcement. Bates was in the Glass Bowl. “We were just happy to be selected. It was an honor to be the first team from Maine in a bowl,” said Art Blanchard.

Besides its record, one reason Bates was considered for a bowl game was the proliferation of such games during the immediate postwar years.

Popping up all over the country, they reflected the optimistic, can-do civic spirit of the time, with names like the Oil Bowl, the Cotton-Tobacco Bowl, the Paper Bowl, the Pretzel Bowl, the Mineral Water Bowl, and the Textile Bowl. Though few of these bowl games are still played today, they mark the beginning of the trend of mixing college sports, business, and commercialism.

The Glass Bowl game, played four times from 1946 to 1949, was typical. After the war, civic and business groups in Toledo had the idea of transforming the university stadium into a true “Glass Bowl.” The city’s major industry was glass — Libbey-Owens-Ford and Owens-Corning, among others, were located in Toledo — and the companies responded by donating materials for a press box, sign, and team houses.

Other plans, more grandiose, were outlined in the 1946 Glass Bowl program: glass dugouts, glass-fiber interlined jackets for players, a glass spire, glass wainscoting for the public rest rooms, heat-treated glass stair railings, and glass enclosures for the box seats. “As glass is fused from many materials,” said the game program, “so are the efforts of Toledo’s groups and industries fused to promote the Glass Bowl.”

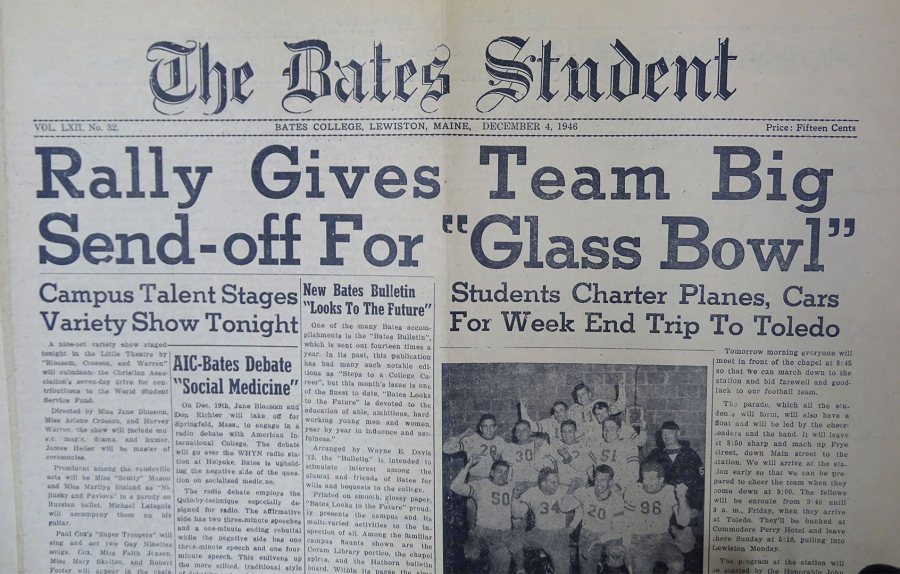

Having accepted the bowl bid, the Bates faced a 24-hour train ride from Lewiston to Ohio, from 9:40 Thursday morning to nine o’clock Friday morning. Some feared the trip would dull the team, but a terrific send-off on Thursday morning put the players in an upbeat mood.

The Dec. 4, 1946, issue of The Bates Student gave support for the Bobcats heading to Ohio for the Glass Bowl.

A pep rally at the Chapel preceded a parade down College Street, up Frye Street, and down Main Street to the train station.The parade route was lined equally with both Lewiston residents and Bates students, who were reminded, in The Bates Student, to “return to campus for their 10 a.m. classes.” Said Linden Blanchard, “We had good support from the community then. Of course, several players were from the area, so they had an interest.”

On the train ride to Ohio, the players kept busy by traded war stories and practicing their Morse code — the “dah dit” sound reminded a Lewiston Evening Journal reporter of “baby talk.” A few took time during a stop off in Boston to visit their families. Arnie Card defended his standing as the best whist player on the team. There was even a little bit of studying going on.

When it came to the game itself, the Bobcats were decided underdogs. They had to cope with opponents who were, on average, 15 pounds heavier and a couple of inches taller from a school with 10 times the enrollment. The Toledo roster had depth, with many positions going two or three deep. “We played both ways, so having a backup was important,” said Linden Blanchard.

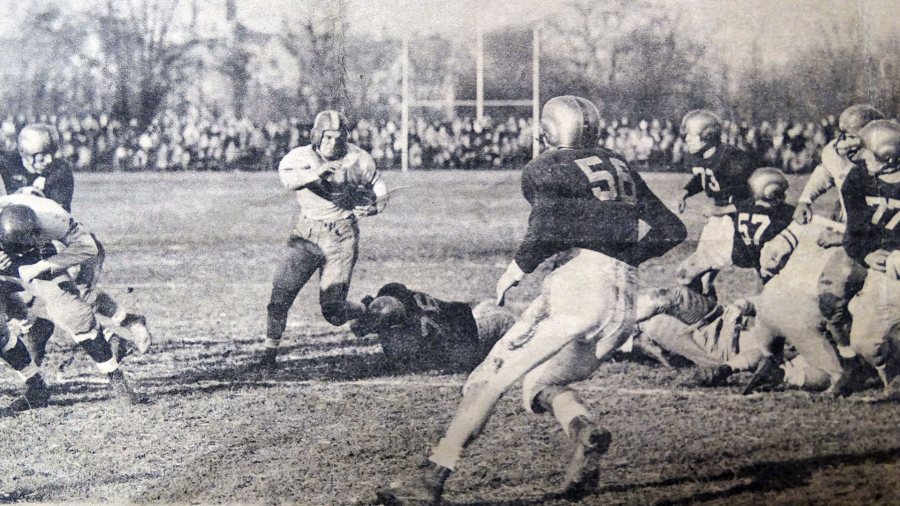

Art Blanchard ’50 carries the ball during the Glass Bowl game on Dec. 7, 1946, between Bates and the University of Toledo. Blanchard was the game MVP.

The game took place on Pearl Harbor Day and included much pageantry to celebrate both the renovated stadium and the conclusion of the first postwar season for both teams. The crowd of 12,000 was treated to five high-school marching bands (“one of the most beautiful spectacles I have ever seen,” wrote Student reporter Dave Tillson ’49), the dedication of the new glass press box, and a 108-flag tribute to all Toledo alumni who had died in the war. The team rosters in the game program even included the military branch that each player served in World War II.

At halftime, the Glass Bowl queen was crowned, and Moore presented an 18-pound Maine lobster, on behalf of Maine governor Horace Hildreth, to Ohio governor Frank Lausche. “With the flags and the new press box it was quite a sight,” said Art Blanchard. “Of course, we had never played in front of that many people before, either.”

The contest was even more exciting, with the Bobcats scoring first. After Art Blanchard went around end for sixteen yards, Bates used some trickery. A run by Walker Heap ’50 went to midfield, where he lateraled to halfback Allen Howlett ’49, who raced the rest of the way to put the Bobcats up, 6-0, after a missed conversion. After holding Toledo several times inside the Bobcat twenty, the Rockets scored twice, once just before and once just after halftime, to take a 14-6 lead into the fourth quarter, where the action really picked up.

On the Bobcats’ first drive of the final quarter, Blanchard completed four passes to the Toledo six and scored on a keeper to cut the lead to 14-12. After two punts, Toledo scored on the big play of the game, a spectacular 54-yard touchdown pass that Bates captain Joe LaRochelle ’47, the shortest man on the team at 5-foot-5, just missed batting away from the Toledo receiver.

The front page of the Dec. 8, 1946, Portland Sunday Telegram features the Glass Bowl result between two other major stories of the day.

With time running out, the Bobcats drove deep into Rocket territory. On first down at the Toledo 22, two Bates receivers had their hands on a goal-line pass (the Evening Journal said they “played volleyball” with the pass), but it dropped incomplete. On second down, an Art Blanchard run took Bates to the eleven for another first down. Two plays later, on a run from the Toledo five, Walker Heap ’50 was stripped of the ball and the Rockets recovered, securing the 21-12 Toledo win.

Though Bates lost, the team earned much respect from their hosts. Art Blanchard, who completed 10 of 20 passes and ran for most of the Bobcats’ 173 rushing yards, was named the game’s outstanding player. According to the Evening Journal, the Toledo players “knew [they] had a fight” on their hands the whole time, while the Lewiston sportswriters, using the partisan logic of a bygone era, noted that “if you take out the 54-yard [Toledo] pass and if Bates recovers the fumble [in the fourth quarter], you’d have an 18-14 win for Bates.”

Lest the college get heady after its excursion into bigger-time athletics, the Bates Alumnus of January 1947 offered this cautionary note in concluding its review of the season: “The postseason game…reflects in no way a change of college athletic policy. Good athletics, consistent with high academic standards, is and will continue to be Bates’s aim.”

By Adam Levin, sports information director

![[Photo: Paul Gastonguay '89, late 1980's]](http://abacus.bates.edu/pubs/mag/96-Fall/sports-notes.photo3.jpg)

New men’s tennis and squash head coach Paul Gastonguay ’89 shown in his Bates playing days

Alumni swell coaching ranks

Paul Gastonguay ’89, the new head coach of men’s tennis and squash, is one of five Bates alumni on the College’s coaching staff in 1996-1997. Gastonguay, a Lewiston native, is the winningest tennis player in Bobcat history. Over his collegiate career, he compiled a 149-41 record in singles and doubles, including the two best seasons by a singles player in school history.

Upon graduation, he competed for four years on the professional circuit and was the training partner for three-time U.S. Open champion Ivan Lendl. In 1991, Gastonguay attained a top-three ranking in the New England Lawn Tennis Association (NELTA) Men’s Open division. Since August 1993, Gastonguay has held the position of assistant tennis director of Lendl’s Grand Slam Health and Tennis Center in Bedford, New York.

Gastonguay takes over the Bates men’s racquets program from George Wigton, who retired last spring after thirty years at the College. “It’s great to be back at Bates,” said Gastonguay. “It hasn’t changed — it’s still such a friendly place.”

“Paul’s playing record, both here and in the professional ranks, speaks for itself,” said Suzanne Coffey, director of athletics. “As someone who learned the game under George Wigton, we know that as a coach, Paul will continue the tradition of excellence and sportsmanship that the program has exhibited for the past thirty years.”

Other alumni on the coaching staff include Sean Galipeau ’96, an assistant cross country coach under head coach Al Fereshetian; Jim Murphy ’69, women’s soccer and basketball coach; Becky Flynn Woods ’89, nordic ski coach, and Greg Youngblood ’94, wide-receivers coach under head football coach Rick Pardy.

In other coaching appointments, John Illig has been named head coach of women’s tennis and squash and Shaw Tilton takes over as head coach of crew, a club sport at the College.

Tilton has previously coached rowing teams at MIT, Simmons College, and Clark University and also spent a year as sculling coach at the Florida Rowing Center in Wellington, Fla.

Illig comes to Bates from Colby, where he was the head coach of the women’s tennis and squash teams. Illig led the Colby women’s tennis team to national prominence during his four-year tenure there, achieving consecutive third-place finishes in New England in 1994-95 and 1995-96 and culminating with a season-ending ranking of twelfth in the NCAA Division III poll, the highest rank in the program’s twenty-eight-year history.